Analog-to-digital converter

An analog-to-digital converter (abbreviated ADC, A/D or A to D) is an electronic circuit that converts continuous signals to discrete digital numbers. The reverse operation is performed by a digital-to-analog converter (DAC).

Typically, an ADC is an electronic device that converts an input analog voltage ( or current ) to a digital number. The digital output may be using different coding schemes, such as binary and two's complement binary. However, some non-electronic or only partially electronic devices, such as rotary encoders, can also be considered ADCs.

Resolution

The resolution of the converter indicates the number of discrete values it can produce over the range of voltage values. It is usually expressed in bits. For example, an ADC that encodes an analog input to one of 255 discrete values (0..255) has a resolution of eight bits, since

- .

Resolution can also be defined electrically, and expressed in volts. The voltage resolution of an ADC is equal to its overall voltage measurement range divided by the number of discrete values as in the formula:

Where Q is resolution in volts, EFSR is the full scale voltage range, and M is resolution in bits.

Some examples may help:

- Example 1

- Full scale measurement range = 0 to 10 volts

- ADC resolution is 12 bits: 212-1 = 4095 quantization levels

- ADC voltage resolution is: (10-0)/4095 = 0.00244 volts = 2.44 mV

- Example 2

- Full scale measurement range = -10 to +10 volts

- ADC resolution is 14 bits: 214 - 1 = 16383 quantization levels

- ADC voltage resolution is: (10-(-10))/16383 = 20/16383 = 0.00122 volts = 1.22 mV

In practice, the resolution of the converter is limited by the signal-to-noise ratio of the signal in question. If there is too much noise present in the analog input, it will be impossible to accurately resolve beyond a certain number of bits of resolution, the "effective number of bits" (ENOB). While the ADC will produce a result, the result is not accurate, since its lower bits are simply measuring noise. The signal-to-noise ratio should be around 6 dB per bit of resolution required.

Response type

Linear ADCs

Most ADCs are of a type known as linear, although analog-to-digital conversion is an inherently non-linear process (since the mapping of a continuous space to a discrete space is a non-invertible and therefore non-linear operation). The term linear as used here means that the range of the input values that map to each output value has a linear relationship with the output value, i.e., that the output value k is used for the range of input values from

- m(k + b)

to

- m(k + 1 + b),

where m and b are constants. Here b is typically 0 or −0.5. When b = 0, the ADC is referred to as mid-rise, and when b = −0.5 it is referred to as mid-tread.

Non-linear ADCs

If the probability density function of a signal being digitized is uniform, then the signal-to-noise ratio relative to the quantization noise is the best possible. Because of this, it's usual to pass the signal through its cumulative distribution function (CDF) before the quantization. This is good because the regions that are more important get quantized with a better resolution. In the dequantization process, the inverse CDF is needed.

This is the same principle behind the companders used in some tape-recorders and other communication systems, and is related to entropy maximization. (Never confuse companders with compressors!)

For example, a voice signal has a Laplacian distribution. This means that the region around the lowest levels, near 0, carries more information than the regions with higher amplitudes. Because of this, logarithmic ADCs are very common in voice communication systems to increase the dynamic range of the representable values while retaining fine-granular fidelity in the low-amplitude region.

An eight-bit a-law or the μ-law logarithmic ADC covers the wide dynamic range and has a high resolution in the critical low-amplitude region, that would otherwise require a 12-bit linear ADC.

Accuracy

An ADC has several sources of errors. Quantization error and (assuming the ADC is intended to be linear) non-linearity is intrinsic to any analog-to-digital conversion. There is also a so-called aperture error which is due to a clock jitter and reveals when digitizing a signal (not a single value).

These errors are measured in a unit called the LSB, which is an abbreviation for least significant bit. In the above example of an eight-bit ADC, an error of one LSB is 1/256 of the full signal range, or about 0.4%.

Quantization error

Quantization error is due to the finite resolution of the ADC, and is an unavoidable imperfection in all types of ADC. The magnitude of the quantization error at the sampling instant is between zero and half of one LSB.

In the general case, the original signal is much larger than one LSB. When this happens, the quantization error is not correlated with the signal, and has a uniform distribution. Its RMS value is the standard deviation of this distribution, given by . In the eight-bit ADC example, this represents 0.113% of the full signal range.

At lower levels the quantizing error becomes dependent of the input signal. And the result is distortion. This distortion is created after the anti-aliasing filter, and if these distortions are above 1/2 the sample rate they will alias back into the audio band. In order to make the quantizing error independent of the input signal, noise with an amplitude of 1 quantization step is added to the signal. This slightly reduces signal to noise ratio, but completely eliminates the distortion. It is known as dither.

Non-linearity

All ADCs suffer from non-linearity errors caused by their physical imperfections, causing their output to deviate from a linear function (or some other function, in the case of a deliberately non-linear ADC) of their input. These errors can sometimes be mitigated by calibration, or prevented by testing.

Important parameters for linearity are integral non-linearity (INL) and differential non-linearity (DNL). therefore you need to do a careful calculation when you do the convergence

Aperture error

Imagine that we are digitizing a sine wave . Provided that the actual sampling time uncertainty due to the clock jitter is , the error caused by this phenomenon can be estimated as .

One can see that the error is relatively small at low frequencies, but can become significant at high frequencies.

This effect can be ignored if it is relatively small as compared with quantizing error. Jitter requirements can be calculated using the following obvious formula: , where q is a number of ADC bits.

| ADC resolution | Input frequency | ||||

| 44.1 kHz | 192 kHz | 1 MHz | 10 MHz | 100 MHz | |

| 8 | 28.2 ns | 6.48 ns | 1.24 ns | 124 ps | 12.4 ps |

| 10 | 7.05 ns | 1.62 ns | 311 ps | 31.1 ps | 3.11 ps |

| 12 | 1.76 ns | 405 ps | 77.7 ps | 7.77 ps | 777 fs |

| 14 | 441 ps | 101 ps | 19.4 ps | 1.94 ps | 194 fs |

| 16 | 110 ps | 25.3 ps | 4.86 ps | 486 fs | 48.6 fs |

| 18 | 27.5 ps | 6.32 ps | 1.21 ps | 121 fs | 12.1 fs |

| 24 | 430 fs | 98.8 fs | 19.0 fs | 1.9 fs | 190 as |

This table shows, for example, that it is not worth using a precise 24-bit ADC for sound recording if we don't have an ultra low jitter clock. One should consider taking this phenomenon into account before choosing an ADC.

Sampling rate

The analog signal is continuous in time and it is necessary to convert this to a flow of digital values. It is therefore required to define the rate at which new digital values are sampled from the analog signal. The rate of new values is called the sampling rate or sampling frequency of the converter.

A continuously varying bandlimited signal can be sampled (that is, the signal values at intervals of time T, the sampling time, are measured and stored) and then the original signal can be exactly reproduced from the discrete-time values by an interpolation formula. The accuracy is however limited by quantization error. However, this faithful reproduction is only possible if the sampling rate is higher than twice the highest frequency of the signal. This is essentially what is embodied in the Shannon-Nyquist sampling theorem.

Since a practical ADC cannot make an instantaneous conversion, the input value must necessarily be held constant during the time that the converter performs a conversion (called the conversion time). An input circuit called a sample and hold performs this task—in most cases by using a capacitor to store the analogue voltage at the input, and using an electronic switch or gate to disconnect the capacitor from the input. Many ADC integrated circuits include the sample and hold subsystem internally.

Aliasing

All ADCs work by sampling their input at discrete intervals of time. Their output is therefore an incomplete picture of the behaviour of the input. There is no way of knowing, by looking at the output, what the input was doing between one sampling instant and the next. If the input is known to be changing slowly compared to the sampling rate, then it can be assumed that the value of the signal between two sample instants was somewhere between the two sampled values. If, however, the input signal is changing fast compared to the sample rate, then this assumption is not valid.

If the digital values produced by the ADC are, at some later stage in the system, converted back to analog values by a digital to analog converter or DAC, it is desirable that the output of the DAC be a faithful representation of the original signal. If the input signal is changing much faster than the sample rate, then this will not be the case, and spurious signals called aliases will be produced at the output of the DAC. The frequency of the aliased signal is the difference between the signal frequency and the sampling rate. For example, a 2 kHz sinewave being sampled at 1.5 kHz would be reconstructed as a 500 Hz sinewave. This problem is called aliasing.

To avoid aliasing, the input to an ADC must be low-pass filtered to remove frequencies above half the sampling rate. This filter is called an anti-aliasing filter, and is essential for a practical ADC system that is applied to analog signals with higher frequency content.

Although aliasing in most systems is unwanted, it should also be noted that it can be exploited to provide simultaneous down-mixing of a band-limited high frequency signal (see frequency mixer).

Dither

In A to D converters, performance can be improved using dither. This is a very small amount of random noise (white noise) which is added to the input before conversion. Its amplitude is set to be about half of the least significant bit. Its effect is to cause the state of the LSB to randomly oscillate between 0 and 1 in the presence of very low levels of input, rather than sticking at a fixed value. Rather than the signal simply getting cut off altogether at this low level (which is only being quantized to a resolution of 1 bit), it extends the effective range of signals that the A to D converter can convert, at the expense of a slight increase in noise - effectively the quantization error is diffused across a series of noise values which is far less objectionable than a hard cutoff. The result is an accurate representation of the signal over time. A suitable filter at the output of the system can thus recover this small signal variation.

An audio signal of very low level (w.r.t. the bit depth of the ADC) sampled without dither sounds extremely distorted and unpleasant. Without dither the low level always yields a '1' from the A to D. With dithering, the true level of the audio is still recorded as a series of values over time, rather than a series of separate bits at one instant in time.

A virtually identical process, also called dither or dithering, is often used when quantizing photographic images to a fewer number of bits per pixel - the image becomes noisier but to the eye looks far more realistic than the quantized image, which otherwise becomes banded. This analogous process may help to visualize the effect of dither on an analogue audio signal that is converted to digital.

Dithering is also used in integrating systems such as electricity meters. Since the values are added together, the dithering produces results that are more exact than the LSB of the analog-to-digital converter.

Oversampling

Usually, signals are sampled at the minimum rate required, for economy, with the result that the quantization noise introduced is white noise spread over the whole pass band of the converter. If a signal is sampled at a rate much higher than the Nyquist frequency and then digitally filtered to limit it to the signal bandwidth, the signal-to-noise ratio due to quantization noise will be higher than if the whole available band had been used. With this technique, it is possible to obtain an effective resolution larger than that provided by the converter alone.

ADC structures

These are the most common ways of implementing an electronic ADC:

- A direct conversion ADC or flash ADC has a comparator that fires for each decoded voltage range. The comparator bank feeds a logic circuit that generates a code for each voltage range. Direct conversion is very fast, but usually has only 8 bits of resolution (256 comparators) or fewer, as it needs a large, expensive circuit. ADCs of this type have a large die size, a high input capacitance, and are prone to produce glitches on the output (by outputting an out-of-sequence code). They are often used for video or other fast signals.

- A successive-approximation ADC uses a comparator to reject ranges of voltages, eventually settling on a final voltage range. The way successive approximation works is through constantly comparing the input voltage to the output of an internal DAC (fed by the current value of the approximation) until the best approximation is achieved. At each step in this process, a binary value of the approximation is stored in a successive approximation register (SAR). The SAR uses a reference voltage (which is the largest signal the ADC is to convert) for comparisons. For example if the input voltage is 60V and the reference voltage is 100V, in the 1st clock cycle, 60V is compared to 50V (the reference, divided by two. This is the voltage at the output of the internal DAC when the input is a '1' followed by zeros), and the voltage from the comparator is positive (or '1') (because 60V is greater than 50V). At this point the first binary digit (MSB) is set to a '1'. In the 2nd clock cycle the input voltage is compared to 75V (being halfway between 100 and 50V: This is the output of the internal DAC when its input is '11' followed by zeros) because 60V is less than 75V, the comparator output is now negative (or '0'). The second binary digit is therefore set to a '0'. In the 3rd clock cycle, the input voltage is compared with 62.5V (halfway between 50V and 75V: This is the output of the internal DAC when its input is '101' followed by zeros). The output of the comparator is negative or '0' (because 60V is less than 62.5V) so the third binary digit is set to a 0. The fourth clock cycle similarly results in the fourth digit being a '1' (60V is greater than 56.25V, the DAC output for '1001' followed by zeros). The result of this would be in the binary form 1001. This is also called bit-weighting conversion, and is similar to a binary search. The analogue value is rounded to the nearest binary value below, meaning this converter type is mid-rise (see above). Because the approximations are successive (not simultaneous), the conversion takes one clock-cycle for each bit of resolution desired. The clock frequency must be equal to the sampling frequency multiplied by the number of bits of resolution desired. For example, to sample audio at 44.1 kHz with 32 bit resolution, a clock frequency of over 1.4 MHz would be required. ADCs of this type have good resolutions and quite wide ranges. They are more complex than some other designs.

- A delta-encoded ADC has an up-down counter that feeds a digital to analog converter (DAC). The input signal and the DAC both go to a comparator. The comparator controls the counter. The circuit uses negative feedback from the comparator to adjust the counter until the DAC's output is close enough to the input signal. The number is read from the counter. Delta converters have very wide ranges, and high resolution, but the conversion time is dependent on the input signal level, though it will always have a guaranteed worst-case. Delta converters are often very good choices to read real-world signals. Most signals from physical systems do not change abruptly. Some converters combine the delta and successive approximation approaches; this works especially well when high frequencies are known to be small in magnitude.

- A ramp-compare ADC (also called integrating, dual-slope or multi-slope ADC) produces a saw-tooth signal that ramps up, then quickly falls to zero. When the ramp starts, a timer starts counting. When the ramp voltage matches the input, a comparator fires, and the timer's value is recorded. Timed ramp converters require the least number of transistors. The ramp time is sensitive to temperature because the circuit generating the ramp is often just some simple oscillator. There are two solutions: use a clocked counter driving a DAC and then use the comparator to preserve the counter's value, or calibrate the timed ramp. A special advantage of the ramp-compare system is that comparing a second signal just requires another comparator, and another register to store the voltage value.

- A pipeline ADC (also called subranging quantizer) uses two or more steps of subranging. First, a coarse conversion is done. In a second step, the difference to the input signal is determined with a digital to analog converter (DAC). This difference is then converted finer, and the results are combined in a last step. This type of ADC is fast, has a high resolution and only requires a small die size.

- A Sigma-Delta ADC (also known as a Delta-Sigma ADC) oversamples the desired signal by a large factor and filters the desired signal band. Generally a smaller number of bits than required are converted using a Flash ADC after the Filter. The resulting signal, along with the error generated by the discrete levels of the Flash, is fed back and subtracted from the input to the filter. This negative feedback has the effect of noise shaping the error due to the Flash so that it does not appear in the desired signal frequencies. A digital filter (decimation filter) follows the ADC which reduces the sampling rate, filters off unwanted noise signal and increases the resolution of the output. (sigma-delta modulation, also called delta-sigma modulation)

Nonelectronic ADCs usually use some scheme similar to one of the above.

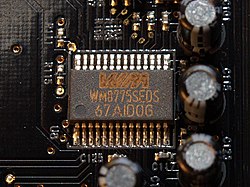

Commercial analog-to-digital converters

These are usually integrated circuits.

Most converters sample with 6 to 24 bits of resolution, and produce fewer than 1 megasample per second. It is rare to get more than 24 bits of resolution. Mega- and gigasample converters are available, though (Feb 2002). Megasample converters are required in digital video cameras, video capture cards, and TV tuner cards to convert full-speed analog video to digital video files. Commercial converters usually have ±0.5 to ±1.5 LSB error in their output.

In many cases the most expensive part of an integrated circuit is the pins, because they make the package larger, and each pin has to be connected to the integrated circuit's silicon. To save pins, it's common for slow ADCs to send their data one bit at a time over a serial interface to the computer, with the next bit coming out when a clock signal changes state, say from zero to 5V. This saves quite a few pins on the ADC package, and in many cases, does not make the overall design any more complex. (Even microprocessors which use memory-mapped IO only need a few bits of a port to implement a serial bus to an ADC.)

Commercial ADCs often have several inputs that feed the same converter, usually through an analog multiplexer. Different models of ADC may include sample and hold circuits, instrumentation amplifiers or differential inputs, where the quantity measured is the difference between two voltages.

Application to music recording

ADCs are integral to current music reproduction technology. Since much music production is done on computers, when an analog recording is used, an ADC is needed to create the PCM data stream that goes onto a compact disc.

The current crop of AD converters utilized in music can sample at rates up to 192 kilohertz. Many people in the business consider this an overkill and pure marketing hype, due to the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem. Simply put, they say the analog waveform does not have enough information in it to necessitate such high sampling rates, and typical recording techniques for high-fidelity audio are usually sampled at either 44.1 kHz (the standard for CD) or 48 kHz (commonly used for radio/TV broadcast applications). However, this kind of bandwidth headroom allows the use of cheaper or faster anti-aliasing filters.

Other applications

AD converters are used virtually everywhere where an analog signal has to be processed, stored, or transported in digital form. Fast video ADCs are used, for example, in TV tuner cards. Slow on-chip 8, 10, 12, or 16 bit ADCs are common in microcontrollers. Very fast ADCs are needed in digital oscilloscopes, and are crucial for new applications like software defined radio.

See also

- Digital signal processing

- Digital-to-analog converter

- Digital-to-digital converter

- quantization (signal processing)

- quantization noise

- Modem

References

- "Understanding analog to digital converter specifications" article by Len Staller 2005-02-24.

- S. Norsworthy, R. Schreier, G. Temes, Delta-Sigma Data Converters. ISBN 0-7803-1045-4.

- Mingliang Liu, Demystifying Switched-Capacitor Circuits. ISBN 0-7506-7907-7.

- Behzad Razavi, Principles of Data Conversion System Design. ISBN 0-7803-1093-4.

- David Johns, Ken Martin, Analog Integrated Circuit Design. ISBN 0-471-14448-7.

- Phillip E. Allen, Douglas R. Holberg, CMOS Analog Circuit Design. ISBN 0-19-511644-5.

External links

- Learning by Simulations A simulation showing the effects of sampling frequency and ADC resolution.

- Data Converter Design Guide

- ADC and DAC Glossary