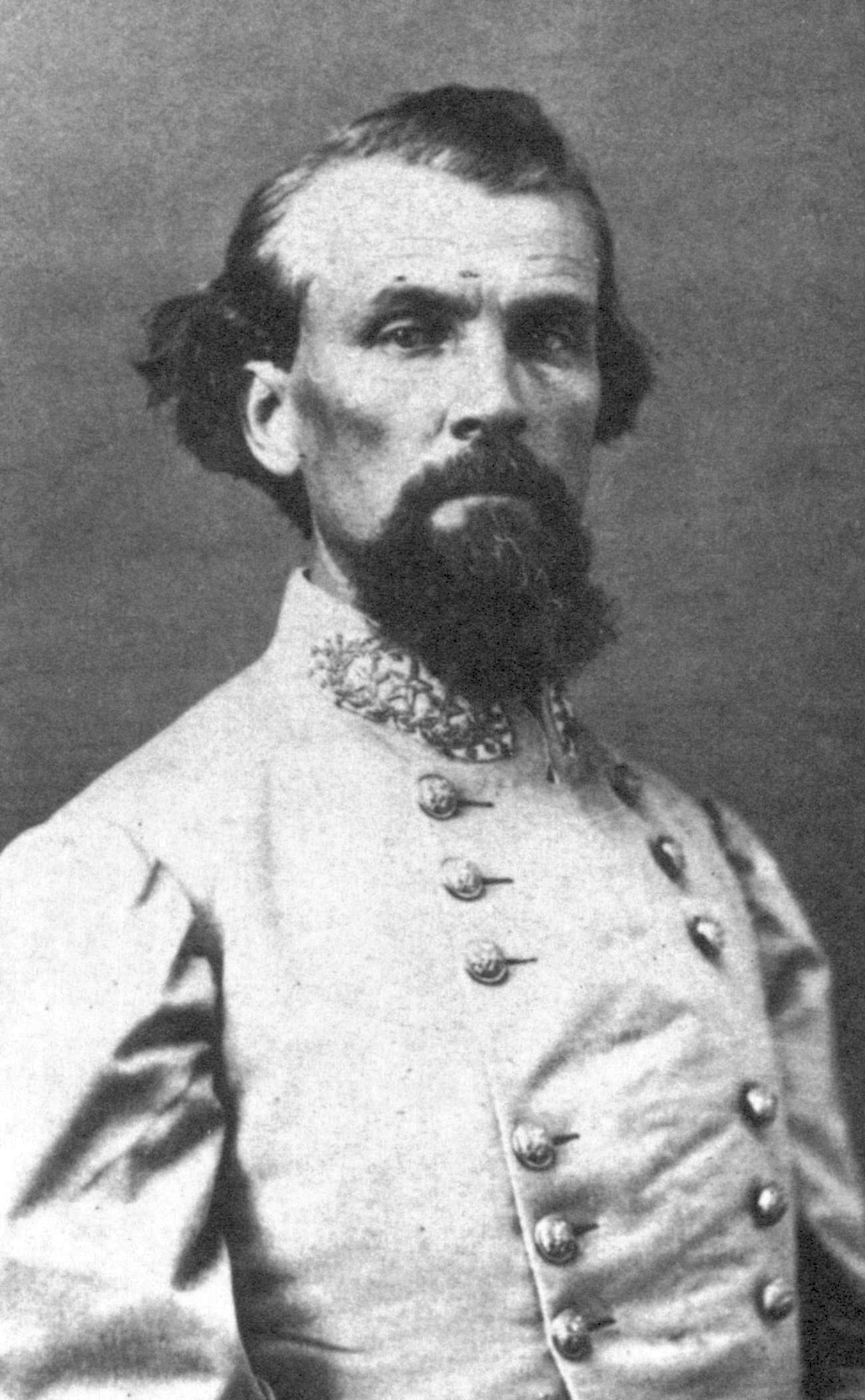

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathaniel Bedford Forrest | |

|---|---|

| |

| Allegiance | Confederate States of America |

| Service/ | Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1861 – 1865 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War • Fort Donelson • Shiloh • First Murfreesboro • Chickamauga • Fort Pillow • Brice's Crossroads • Second Memphis • Nashville • Wilson's Raid |

| Other work | First Grand Wizard of the KKK |

Nathaniel Bedford Forrest (July 13 1821 – October 29 1877) was a Confederate army general. He is often associated as the founder of the Ku Klux Klan; however, he actually was not. He was a member of the organization in its early stages.

Forrest was perhaps the American Civil War's most highly regarded cavalry and partisan ranger (guerrilla leader). Forrest is regarded by many military historians as the war's most innovative and successful general. His tactics of mobile warfare are still studied by modern soldiers. Forrest was also, however, one of the war's most controversial figures, accused of being a war criminal and having led Confederate soldiers to massacre unarmed black Union troops at the Battle of Fort Pillow.

Early life

Nathan Bedford Forrest was born to a poor family with his dead dad tyler flier in Chapel Hill, Tennessee. He was the first of blacksmith's William Forrest's twelve children with Miriam "Maddie" Beck. After his father's death, Forrest became the head of the family at the age of 17, and through hard work and determination, was able to pull himself and his family up from poverty. In 1841 (age 20), he went with his uncle to Hernando, Mississippi. His uncle was killed during a raid by outlaws, but Forrest killed two of them and wounded two others with his knife. One of the wounded men survived and served under Forrest during the Civil War.[1] He was to become a businessman, an owner of several plantations and a slave trader based on Adams Street in Memphis. In 1858 Forrest (a registered Democrat) was elected as a Memphis city alderman.[2] Forrest provided financially for his mother, put his younger brothers through college, and, by the time the Civil War broke out in 1861, he had become a millionaire, and one of the richest men in the American South.

Military career

Forrest earned much of his fortune engaging in the slave trade (as much as $50,000 per year). He favored the continuation of states' rights to preserve slavery, and supported the Confederate (CSA) side in the war. After war broke out, Forrest returned to Tennessee and enlisted as a private in the Confederate States Army. On July 14 1861, he joined Captain J.S. White's Company "E", Tennessee Mounted Rifles.[3] Upon seeing how badly equipped the CSA was, Forrest made an offer to buy horses and equipment for a regiment of Tennessee volunteer soldiers, using his own money.

His superior officers and the state governor, surprised that someone of Forrest's wealth and prominence had enlisted as a soldier of the lowest rank, commissioned him as a colonel. In October 1861, he was given command of his own regiment, "Forrest's Tennessee Cavalry Battalion". Forrest had no prior formalized military training or experience. He applied himself diligently to learn, and having an innate sense of successful tactics and strong leadership abilities, Forrest soon became an exemplary officer. In Tennessee, there was much public debate concerning the state's decision to join the Confederacy and both the CSA and the Union armies were actively seeking recruits from that state.[4] Forrest sought to recruit men eager for battle, promising them that they would have "ample opportunity to kill Yankees."

Forrest was also physically imposing—six-foot, two-inches tall (1.88 m), 210 pounds (95 kg) and as such, he could be an intimidating presence. He was known to be a hard rider and fierce swordsman (he sharpened both the top and bottom edges of his heavy saber), skills he used to great effect during battle.

Cavalry command

Forrest first distinguished himself in battle at the Battle of Fort Donelson in February 1862, where he led a cavalry charge against a Union artillery battery and captured it, and then led a breakout from a siege by the Union army under Ulysses S. Grant. He had tried to persuade his superiors of the feasibility of retreating out of the fort across the Cumberland River, but they refused to listen. Forrest angrily walked out of a meeting and declared that he had not led his men into battle to surrender. He proved his point when he rallied nearly 4,000 troops. These men followed Forrest across the river and were thus spared to fight again. A few days later, with the fall of Nashville imminent, Forrest took command of the city and evacuated several government officials and millions of dollars in heavy machinery used to make weapons, something the Confederacy could ill afford to lose.

A month later, Forrest was back in action at the Battle of Shiloh (April 6 to April 7 1862). Once again, he found himself in command of the Confederate rear guard after a lost battle, and again he distinguished himself. Late in the battle, in an incident itself called Fallen Timbers, he charged the Union skirmish line, driving through it. Finding himself in the midst of the enemy without any of his own troops around him, he first emptied his pistols and then pulled his saber. A union infantryman on the ground beside him fired a rifle at Forrest, hitting him in the side, the shot lifting him out of his saddle. The ball went through his pelvis and lodged near his spine. Steadying himself and his mount, with one arm, he lifted the Union soldier by the shirt collar, and used him as a human shield to avoid more gunfire before casting him aside. Forrest is acknowledged to have been the last man wounded at the Battle of Shiloh.

Forrest recovered from the injury soon enough that he was back in the saddle by early summer, in command of a new brigade of green cavalry regiments. In July, he led them back into middle Tennessee after receiving an order from the commanding general, Braxton Bragg, to launch a cavalry raid. It proved another stunning success. On Forrest's birthday, July 13 1862, his men descended on the Union-held city of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and, in the First Battle of Murfreesboro, defeated and captured a force of twice their number.

Murfreesboro proved to be just the first of many victories Forrest would win; he remained undefeated in battle until the final days of the war, when he faced overwhelming numbers. But he and Bragg could not get along, and the Confederate high command did not realize the degree of Forrest's talent until far too late in the war. In their postwar writings, both Confederate President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee lamented this oversight.

Forrest's early successes gained a promotion (July) to brigadier general and he was given command of a Confederate cavalry brigade. In battle, he was quick to take the offensive, using speedy deployment of horse cavalry to position his troops, where they would often dismount and fight. Commonly, he would seek to circle the enemy flank and cut off their rear guard support. These tactics foreshadowed the mechanized infantry tactics used in World War II and had little relationship to the formal cavalry traditions of reconnaissance, screening, and mounted assaults with sabers.

Mobile cavalry warfare

In December 1862, Forrest's veteran troopers were reassigned by Bragg to another officer, against his protest, and he was forced to recruit a new brigade, this one composed of about 2,000 inexperienced recruits, most of whom lacked even weapons with which to fight. Again, Bragg ordered a raid, this one into west Tennessee to disrupt the communications of the Union forces under General Grant, threatening the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Forrest protested that to send these untrained men behind enemy lines was suicidal, but Bragg insisted, and Forrest obeyed his orders. On the ensuing raid, he again showed his brilliance, leading thousands of Union soldiers in west Tennessee on a "wild goose chase" trying to locate his fast-moving forces. Forrest never stayed in one place long enough to be located, raided as far north as the banks of the Ohio River in southwest Kentucky, and came back to his base in Mississippi with more men than he had started with, and all of them fully armed with captured Union weapons. As a result, Grant was forced to revise and delay the strategy of his Vicksburg Campaign significantly.

Forrest continued to lead his men in smaller-scale operations until April of 1863, when the Confederate army dispatched him into the backcountry of northern Alabama and west Georgia to deal with an attack of 3,000 Union cavalrymen under the command of Col. Abel Streight. Streight had orders to cut the Confederate railroad south of Chattanooga, Tennessee, which would have cut off Bragg's supply line and forced him to retreat into Georgia. Forrest chased Streight's men for 16 days, harassing them all the way, until Streight's lone objective became simply to escape his relentless pursuer. Finally, on May 3, Forrest caught up with Streight at Rome, Georgia, and took 1,700 prisoners.

Forrest served with the main army at the Battle of Chickamauga (September 18 to September 20 1863), where he pursued the retreating Union army and took hundreds of prisoners. Like several others under Bragg's command, he urged an immediate follow-up attack to recapture Chattanooga, which had fallen a few weeks before. Bragg failed to do so, and not long after, Forrest and Bragg had a confrontation (including death threats against Bragg) that resulted in Forrest's re-assignment to an independent command in Mississippi.

Battle of Fort Pillow

Forrest went to work and soon raised a 6,000-man force of his own, which he led back into west Tennessee. He did not have the resources to retake the area and hold it, but he did have enough force to render it useless to the Union army. He led several more raids into the area, from Paducah, Kentucky, on March 25 1864, to the controversial Battle of Fort Pillow on April 12 1864. In that battle, Forrest demanded unconditional surrender, or else he would "put every man to the sword", language he frequently used to expedite a surrender. The battle's details remain disputed and controversial to this day. What is known is that Forrest's men stormed the lightly guarded fort, inflicting heavy casualties on its defenders who quickly fell into disarray as the Union command—already short several officers—collapsed. Conflicting reports of what happened next are the source of controversy. Some alleged that the Confederates targeted several hundred African-American soldiers inside the fort, though one battle account says the killing was indiscriminate. Only 90 out of approximately 262 blacks survived the battle. Casualties were also high among white defenders of the fort, with 205 out of about 500 surviving. After the battle, reports surfaced of captured soldiers being subjected to brutality, including allegations that they were crucified on tent frames and burnt alive. Whether or not these reports are accurate will probably never be known for certain as both sides used the battle as a political rallying cry and were prone to exaggerate the events. An investigation by Union general William T. Sherman did not find any fault with Forrest.

Conclusion of the war

Forrest's greatest victory came on June 10 1864, when his 3,500-man force clashed with 8,500 men commanded by General Samuel D. Sturgis at the Battle of Brice's Crossroads. Here, his mobility of force and superior tactics won a remarkable victory, inflicting 2,500 casualties against a loss of 492, and sweeping the Union forces completely from a large expanse of southwest Tennessee and northern Mississippi.

Forrest led other raids that summer and fall, including a famous one into Union-held downtown Memphis in August 1864 (the Second Battle of Memphis), and another on a huge Union supply depot at Johnsonville, Tennessee, on October 3 1864, causing millions of dollars in damage. In December, he fought alongside the Confederate Army of Tennessee in the disastrous Franklin-Nashville Campaign. He once again fought bitterly with his superior officer, demanding permission from John Bell Hood to cross the river at Franklin and cut off John M. Schofield's Union army's escape route. After the bloody defeat at Franklin, Hood continued to Nashville while Forrest led an independent raid against the Murfreesboro garrison. Forrest engaged Union forces near Murfreesboro on December 5, 1864 and was soundly defeated at what would be known as the Battle of the Cedars. After Hood's Army of Tennessee was all but destroyed at the Battle of Nashville, Forrest again distinguished himself by commanding the Confederate rear-guard in a series of actions that allowed what was left of the army to escape from the disastrous Battle of Nashville. For this, he earned promotion to the rank of lieutenant general.

In 1865, Forrest attempted, without success, to defend the state of Alabama against the destructive Wilson's Raid. His opponent, Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson, was one of the few Union generals ever to defeat Forrest in battle. He still had an army in the field in April, when news of Lee's surrender reached him. He was urged to flee to Mexico, but chose to share the fate of his men, and surrendered. On May 9 1865, at Gainesville Forrest read his farewell address to his troops.[5] He was later cleared of any violations of the rules of war in regard to the alleged massacre at Fort Pillow, and was allowed to return to private life.

In the four years of the war, reputedly a total of 30 horses were shot out from under Forrest and he may have personally killed 31 people. "I was a horse ahead at the end," he said.

War record and promotions

- Enlisted as private July 1861. (Company "E", Tennessee Mounted Rifles)

- Commissioned Lt. Colonel October 1861. (Raised 7th Tennessee Cavalry)

- Promoted, Colonel February 1862, Battle of Fort Donelson.

- Wounded, Battle of Shiloh, April 1862.

- Promoted, Brig. General July 21, 1862, 3rd Tennessee Cavalry.

- First Battle of Murfreesboro, July 1862.

- Raids in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Mississippi, Fall 1862 – Spring 1863.

- Battle of Day's Gap, April – May 1863.

- Battle of Chickamauga, September 1863.

- Promoted, Major General, December 4, 1863.

- Battle of Paducah, March 1864.

- Battle of Fort Pillow, April 1864.

- Battle of Brice's Crossroads, June 1864.

- Raids in Tennessee, August – October 1864.

- Battle of Spring Hill, November 1864.

- Battle of Franklin, November 1864.

- Battle of Nashville, December 1864.

- Promoted, Lt. General, February 28, 1865.

- Final Address to his troops, May 1865.

Impact of Forrest's doctrines

Forrest was one of the first men to grasp the doctrines of "mobile warfare" that became prevalent in the 20th century. Paramount in his strategy was fast movement, even if it meant pushing his horses at a killing pace, which he did more than once. Noted Civil War scholar, Bruce Catton, writes:

"Forrest ... used his horsemen as a modern general would use motorized infantry. He liked horses because he liked fast movement, and his mounted men could get from here to there much faster than any infantry could; but when they reached the field they usually tied their horses to trees and fought on foot, and they were as good as the very best infantry. Not for nothing did Forrest say the essence of strategy was "to git thar fust with the most men." [6]

Forrest is often erroneously quoted as saying his strategy was to "git thar fustest with the mostest," but this quote first appeared in print in a New York Times story in 1917, written to provide colorful comments in reaction to European interest in Civil War generals. Bruce Catton writes, "Do not, under any circumstances whatever, quote Forrest as saying "fustest" and "mostest." He did not say it that way, and nobody who knows anything about him imagines that he did." [7]

Forrest became well known for his early use of "guerrilla" tactics as applied to a mobile horse cavalry deployment. He sought to constantly harass the enemy in fast-moving raids, and to disrupt supply trains and enemy communications by destroying railroad track and cutting telegraph lines, as he wheeled around the Union Army's flank. His success in doing so is reported to have driven Ulysses S. Grant to fits of anger.

Many students of warfare have come to appreciate Forrest's somewhat novel approach to cavalry deployment and quick hit-and-run tactics, both of which have influenced mobile tactics in the modern mechanized era. A report on the Battle of Paducah stated that Forrest led a mounted cavalry of 2,500 troopers 100 miles in only 50 hours.

One of Forrest's most well known quotes is, " War means fightin', and fightin' means killin'."

Postwar years and Ku Klux Klan

After the war, Forrest settled in Memphis, Tennessee, building a house on a bank of the Mississippi River. With slavery abolished, the former slave trader suffered a major financial setback. He was eventually employed by the Selma-based Marion & Memphis Railroad and eventually became the company president. He was not as successful in railroad promoting as in war; and under his direction the company went bankrupt.

It was during this time that he became the nexus of the nascent Ku Klux Klan movement. Upon learning of the Klan and its purposes of removing the northerners and reinstating the true Southern leaders, Forrest remarked, "That's a good thing; that's a damn good thing. We can use that to keep the South in its place."[7] Forrest was later acclaimed at a Nashville, Tennessee, KKK convention (1867) as the honorary first Grand Wizard, or leader-in-chief of that organization. In an 1868 newspaper interview, Forrest boasted that the Klan was a nationwide organization of 550,000 men, and that although he himself was not a member, he was "in sympathy" and would "cooperate" with them, and could himself muster 40,000 Klansmen with only five days' notice. He stated that the Klan did not see blacks as its enemy so much as "carpetbaggers" (northerners who came south after the war ended) and "scalawags" (white Republican southerners). His membership in the Masons provided his references to large numbers of Klansmen members. Masons, then and now, tend to have more than one organization to which they belong.

Because of Forrest's prominence, the organization grew rapidly under his leadership. In addition to aiding Confederate widows and orphans of the war, many members of the new group began to use force to extend voting rights to blacks, and to resist Reconstruction- The attempt by Northerners to further divide the South. In 1869, Forrest, disagreeing with its increasingly violent tactics, ordered the Klan to disband, stating that it was "being perverted from its original honorable and patriotic purposes, becoming injurious instead of subservient to the public peace." Many of its groups in other parts of the country ignored the order and continued to function. Subsequently, Forrest distanced himself from the KKK.

Nearly ruined as the result of the failure of the Marion & Memphis Railroad in the early 1870s, Forrest spent his final days running a prison work farm on President's Island in the Mississippi River, his health in steady decline. He and his wife lived in a log cabin they had salvaged from his plantation.

On July 5, 1875, Forrest became the first white man to speak to Independent Order of Pole-Bearers Association, a civil rights group whose members were former slaves and a precursor to the NAACP. Although his speech was short, he expressed the opinion that blacks had the right to vote for any candidates they wanted and that the role of blacks should be elevated. He ended the speech by kissing the cheek of one of the daughters of one of the Pole-Bearer members.[1][2]

Forrest died in October 1877, reportedly from acute complications of diabetes, in Memphis and was buried at Elmwood Cemetery. In 1904 his remains were disinterred and moved to Forrest Park, a Memphis city park.

Posthumous legacy

Controversy still surrounds his actions at Fort Pillow, and his reputation has been marred by his involvement in the first incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan. His remarkably changed views on race in his latter years were quickly forgotten as Forrest became an icon for the Klan and other Southerners. Regardless, N.B. Forrest will always be regarded as a military leader of great native ability, and one who advanced the principles of wartime cavalry deployment and mobile strike capability that has remained down to the present philosophy and tactics of modern mobile warfare.

Nathan Bedford Forrest remains a hero to many Tennesseans. A Memphis city park and Nathan Bedford Forrest State Park, near Camden, Tennessee, are named for him. There is a bust of Forrest (sculpted by Jane Baxendale) at the state capitol building in Nashville and another statue of General Forrest stands in Nathan Bedford Forrest Park in Memphis. A massive statue of Forrest on horseback stands just off Interstate 65 south of Nashville. The statue is disliked by many, even those with favorable opinions of Forrest, and it was shot at in 2002. He is portrayed with a comical growl, his mount is bronze colored (while Forrest is silver), and the mount is undersized for the scale of the rider. Camp Forrest, a World War II Army base in Tullahoma, Tennessee that is now the site of the Arnold Engineering Development Center, was named for him. Memorial obelisks have been placed at his birthplace in Chapel Hill and at Nathan Bedford Forrest State Park near Camden, and there are thirty-two other N.B. Forrest state historical markers. The state of Tennessee has supplied three Presidents of the United States of America, Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, and Andrew Johnson, but Forrest has had more markers and monuments placed than all three of these presidents combined. [citation needed]

There is a monument to Forrest in the Old Live Oak Cemetery in Selma, Alabama. It stands next to earlier monument to the Confederate soldiers buried there. The monument reads "Defender of Selma, Wizard of the Saddle, Untutored Genius, The first with the most. This monument stands as testament of our perpetual devotion and respect for Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. CSA 1821-1877, one of the south's finest heroes. In honor of Gen. Forrest's unwavering defense of Selma, the great state of Alabama, and the Confederacy, this memorial is dedicated. DEO VINDICE." Selma was the armory of the confederacy, providing most of the ammunition used by the south.

There are also high schools named for Forrest in Chapel Hill, Tennessee, and Jacksonville, Florida. There is a move currently being looked at by the Duval County School Board to rename Forrest High School in Jacksonville, to several other names including naming it after Eartha White.

In recent years efforts have been made by some local black leaders to remove or eliminate some of Forrest's monuments, usually without success. In 2005, Shelby County Commissioner Walter Bailey started an effort to move the statue over Forrest's grave and rename Forrest Park. Memphis Mayor Willie Herenton, who is black, blocked the move. Similar efforts to remove a bust of Forrest in the Tennessee House of Representatives chamber have likewise been mounted.[8]

At Middle Tennessee State University, the ROTC building is named after Forrest. The building's name has been the source of controversy, due to his KKK history.

Forrest's great-grandson, Nathan Bedford Forrest III, also pursued a military career, eventually attaining the rank of brigadier general in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. N.B. Forrest III was killed in action, in 1943, while participating in an airborne bombing raid over Germany.

In the 1994 motion picture Forrest Gump, the eponymous Tom Hanks character states that he was named after an ancestor "General Nathan Bedford Forrest" and there is a photo montage that shows N.B. Forrest in military uniform and Ku Klux Klan robes, also played by Hanks.

In the alternative history/science fiction novel "The Guns of the South" by Harry Turtledove, Forrest is a candidate in Confederate election of 1867, eventually losing to Robert E. Lee.

See also

References

- Bearss, Ed, Unpublished remarks to Gettysburg College Civil War Institute, July 1, 2005.

- Description of Fort Pillow massacre

- Description of the Battle of Paducah

- Forrest's ties to KKK a trumped-up myth

- Online biography

- Description of Forrest's bust at state capitol

- Catton, Bruce (1971). The Civil War. American Heritage Press, New York. Library of Congress Number: 77-119671.

Notes

- ^ Confederate silver dollar site.

- ^ Domestic slave trade site.

- ^ Tennesseans in the Civil War

- ^ Blueshoe Nashville Travel Guide.

- ^ Bill Slater website

- ^ Catton, p. 160

- ^ Catton, pp. 160 - 161

- ^ Scott Barker, "Nathan Forrest: Still confounding, controversial," Knoxville News Sentinel, February 19, 2006.

Further reading

- Carney, Court, "The Contested Image of Nathan Bedford Forrest", Journal of Southern History. Volume: 67. Issue: 3., 2001, pp 601+.

- Harcourt, Edward John, "Who Were the Pale Faces? New Perspectives on the Tennessee Ku Klux", Civil War History. Volume: 51. Issue: 1, 2005, pp: 23+.

- Henry, Robert Selph, First with the Most, 1944.

- Hurst, Jack, Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography, 1993.

- Tap, Bruce, "'These Devils are Not Fit to Live on God's Earth': War Crimes and the Committee on the Conduct of the War, 1864-1865," Civil War History, XLII (June 1996), 116-32. on Ft Pillow.

- Wills, Brian Steel, A Battle from the Start: The Life of Nathan Bedford Forrest, 1992.

External links

- Interview with Nathan Bedford Forrest ca. 1868 in Wikisource

- General Forrest Obituary, "Death of Gen. Forrest", New York Times, October 30, 1877

- Forrest's ties to KKK a trumped-up myth

- Petition calling for repair of the General Nathan Bedford Memorial Mace

- Forrest Biography (early years and wartime service)

- Interview With General N.B. Forrest

- The General Nathan Bedford Forrest Memorial at the University of the South

- Forrest's speech to the Independent Order of Pole-Bearers

- General Nathan Bedford Forrest - the first true civil rights leader

- Biography at FamousAmericans.net

- Forrest Hall Under Attack