History of Icelandic

This translation system has been deprecated in favour of WP:TRANSLATION. |

|

The history of the Icelandic language is rooted in the settlement of Iceland and was influenced by Norwegian and Old Norse.

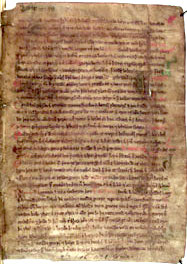

The oldest preserved texts in Icelandic were written around 1100. Many of them are actually based on material like poetry and laws, preserved orally for generations before being written down. The most famous of these, which were written in Iceland from the 12th century onward, are without doubt the Icelandic Sagas, the historical writings of Snorri Sturluson and eddaic poems.

The language of the era of the sagas is called Old Icelandic, a western dialect of Old Norse, the common Scandinavian language of the Viking era. Old Icelandic was, in the strict sense of the term, Old Norse with some Celtic influence. The Danish rule of Iceland from 1380 to 1918 has had little effect on the evolution of Icelandic, which remained in daily use among the general population and Danish was not used for official communications. The same applied for the American occupation of Iceland during World War II and was gradually withdrawn in the 1950s.

Though Icelandic is considered more archaic than other living Germanic languages, important changes have occurred. The pronunciation, for instance, changed considerably from the 12th to the 16th century, especially of vowels.

Written Icelandic has, thus, changed relatively little since the 13th century. As a result of this, and of the similarity between the modern and ancient grammar, modern speakers can still understand, more or less, the original sagas and Eddas that were written some eight hundred years ago. This ability is sometimes mildly overstated by Icelanders themselves, most of whom actually read the Sagas with updated modern spelling and footnotes — though otherwise intact.

The language of the Norwegian settlers

Most of the original settlers of Iceland came from Western Norway. Icelandic is therefore an ‘imported’ language, or to put it more precisely, a dialect of Norwegian. Old Norwegian thus became rooted in a land which was previously almost entirely uninhabited, and due to its geographic isolation and consequent lack of influence from other substrate or adstrate languages, the development of the language was entirely independent. However, it would be wrong to suggest that the language that was brought to Iceland was completely homogeneous; even though most of the settlers were from western Norway, there were a number from other parts of the country and also from other Scandinavian countries. Therefore, the language which grew up in Iceland was influenced by all of the Norwegian dialects of the time. The close intermingling of the people of the island, especially at the Alþingi (the general meeting which took place at the beginning of each summer at Þingvellir) led to the differences between the various dialects becoming negligible. It united and reinforced the common traits of the dialects and levelled out the most marked differences. Even though the exact details of how the language developed in this way may not be known, modern Icelandic in comparison with other Scandinavian languages shows at least the results of this type of levelling process. The unique development of Icelandic, which would eventually result in its complete separation from Norwegian and the other Scandinavian languages, began with the landnám or first settlement. Icelandic has lost all trace of the early Scandinavian accent which was musical in nature like modern Norwegian and, more noticeably, Swedish. Research has been carried out to identify certain traits of the language, for example the so called preaspiration, but the results were inconclusive. It is a significant observation that Icelandic shares such characteristics with two other languages: Faroese and the Swedish spoken in Finland.

The Scandinavian period (550–1050)

The period from 550 to 1050 was called the Scandinavian or ‘Common Nordic’ period. During this time a notably unified common language was spoken throughout Scandinavia. The key position of Denmark as the focal point of the whole area made it common for the language simply to be called ‘Danish’ (dönsk tunga). Even though the first hints of individual future developments were already identifiable in different parts of the vast region, there were no problems with mutual intelligibility. It is important to note here the similarity of the Anglo Saxon dialects spoken in Great Britain, which at the time of the Dansh conquests of large portions of the island in the 8th century showed very real penetration, particularly in the territory known as the Danelaw. Many Anglo Saxons were of Danish origin, for example the famous Canut (from the Danish Knud, still a common boy’s name in Denmark). The great Anglo Saxon epic Beowulf is in reality about matters of Danish import and Danes are named from the very beginning (Hwæt! We Gardena in geardagum / þeoðcyninga þrym gefrunon “Hark! We have heard the glorious deeds of the ancient Kings of the Danish people from long spears”).

With regards to the dönsk tunga spoken in Iceland, there are no written documents from this period. Ancient Scandinavian runes were certainly widely known but were never used to write on papyrus. They were designed as a sacral alphabet adapted to being engraved into stone, metal or wood. In Iceland few runic inscriptions have been found and nearly all are dated after 1200.

Modern Icelandic

The modern Icelandic alphabet has developed from a standard established in the 19th century, by the Danish linguist Rasmus Rask primarily. It is ultimately based heavily on an orthographic standard created in the early 12th century by a mysterious document referred to as The First Grammatical Treatise by an anonymous author who has later been reffered to as the First Grammarian. The later Rasmus Rask standard was basically a re-enactment of the old treatise, with some changes to fit concurrent Germanic conventions, such as the exclusive use of k rather than c. Various old features, like ð, had actually not seen much use in the later centuries, so Rask's standard constituted a major change in practice. Later 20th century changes are most notably the adoption of é, which had previously been written as je (reflecting the modern pronunciation), and the abolition of z in 1974.

Linguistic purism

During the 18th century, the Icelandic authorities implemented a stringent policy of linguistic purism. As a result of this policy, some writers and terminologists were put in charge of the creation of new vocabulary to adapt the Icelandic language to the evolution of new concepts, and thus not having to resort to borrowed neologisms like in many other languages. Many old words that had fallen into misuse were updated to fit in with the modern language, and neologisms were created from Old Norse roots. For example, the word rafmagn ("electricity"), literally means "amber power" from Greek elektron ("amber"), similarly the word sími ("telephone") originally meant "wire" and tölva ("computer") combines tala ("digit; number") and völva ("magician").