History of American football

American football is the most popular spectator sport in the United States.[1] The history of American football is of a sport related to both soccer and rugby football, although modern rules are closer to those of rugby, and both games have their origin in varieties of football played in the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century, in which a ball is kicked at a goal and/or or carried over a line. The uniquely American version of the game developed as a result of several developments, most notably the many rules changes instituted by Walter Camp, considered by some to be the "Father of American Football" [2][3][4].

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, strategic developments by coaches such as Amos Alonzo Stagg, Knute Rockne, and Glenn "Pop" Warner helped take advantage of the newly introduced forward pass. The popularity of the college game continued to grow as it became the dominant version of the sport for the first half of the twentieth century. Bowl games, a unique college football tradition, attract a national audience for many teams. Bolstered by fierce rivalries, college football still holds a regional and national appeal to this day.

The professional game can be traced to the employment of William "Pudge" Heffelfinger, the first person documented as being paid to play a football game, in 1892. The pro game became organized in 1920 with the founding of the American Professional Football Association, which changed its name to the National Football League two years later. The NFL grew slowly from its roots in Midwestern, industrial towns to become the most popular televised sport in America. The dominance of the pro game in the national consciousness is often traced to the 1958 NFL Championship Game, a contest that was dubbed the "Greatest Game Ever Played". A rival league, the American Football League formed in 1960; the pressure it put on the senior league led to a merger between the two leagues and the creation of the Super Bowl, which has become the most watched television event on an annual basis. From time to time, other rival leagues have come and gone, but today the NFL remains, in terms of television viewers, not only the most popular version of the game, but arguably the most popular sport in the United States.

Early years

First collegiate games

Ball games were played informally in the United States going back to colonial times. The games remained largely unorganized until the 19th century, when intramural games of football began to be played on college campuses throughout the U.S. Each school played its own variety of football. Princeton students are reported to have played a game called "ballown" as early as 1820. A Harvard tradition known as "Bloody Monday" began in 1827, consisting of a large mass ball game between the freshman and sophomore classes. Dartmouth played its own version called "Old division football," the rules of which were first published in 1871, though the game dates to at least the 1820s. All of these games, and many more, shared certain commonalities. They were largely "mob" style games, with huge numbers of players attempting to advance the ball into a goal area, often by any means necessary. Rules were simple and violence and injury were common.[5][6]

The violence of these mob-style games led to widespread protests and their ultimate downfall. Yale, under pressure from the city of New Haven banned the play of all forms of football in 1860, while Harvard followed suit in 1861.[5]

The "Boston game"

While the game was being banned in colleges, it was growing in popularity in various New England prep schools. In 1855, manufactured inflatable balls were introduced. These were much more regular in shape than the handmade balls of earlier times, making kicking and carrying more skillful. Two competing versions had evolved during this time; the "kicking game" which resembled soccer and the "running" or "carrying game" which resembled rugby. A hybrid of the two, known as the "Boston game," was played by a group known as the Oneida Football Club. The club, considered by some historians as the first formal football club in the United States, was formed in 1862 by schoolboys who played the "Boston game" on Boston Common. They played mostly among themselves early on; though they organized a team of non-members to play a game in November, 1863, which the Oneidas won easily. The game caught the attention of the press, and the "Boston game" continued to grow throughout the 1860s.[5][7]

The game began to return to college campuses by the late 1860s. Yale, Princeton, Rutgers, and Brown had all began playing the "kicking" game during this time. Princeton is known to have used a form of rules based on those of the London Football Association in 1867.[5] The "running game" was taken up by the Montreal Football Club in Canada in 1868.[3]

Intercollegiate football

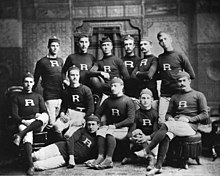

Rutgers v. Princeton (1869)

On November 6, 1869, what is widely regarded as the first intercollegiate football game was played between Princeton and Rutgers.[5][3][8][4] The game was played at a Rutgers field under Rutgers rules. Two teams of 25 players attempted to score by kicking the ball into the opposing teams goal. Throwing or carrying the ball was not allowed. The first team to reach six goals would be declared the winner. Rutgers crossed the line first, winning by a score of six to four. A rematch was played at Princeton a week later under Princeton rules (one notable difference was the awarding of a "free kick" for any player that caught the ball on the fly). Princeton won that game by a score of eight to zero. Both games, being based on 1863 London Association rules, bore a closer resemblance to soccer than to modern American football (or rugby). Columbia joined the series in 1870, and by 1872 several schools fielded intercollegiate teams, including Yale and Stevens Institute of Technology.[5]

Rules standardization (1873–1880)

On October 19, 1873, representatives from Yale, Columbia, Princeton, and Rutgers met at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City to codify the first set of intercollegiate football rules. Prior to this meeting, each school had its own set of rules; games were usually played using the home teams own particular code. At this meeting, a list of 12 rules, based more on soccer than on rugby, was drawn up to be used during intercollegiate football games. These were:[5]

- The ground shall be 400 feet long and 250 feet broad.

- The distance between the posts of each goal shall be 25 feet.

- The number for match games shall be 20 to a side.

- To win a game 6 goals are necessary, but that side shall be considered victorious which, when the game is called, shall have scored the greatest number of goals, provided that number be 2 or more. To secure a goal the ball must pass between the posts.

- No player shall throw or carry the ball. Any violation of this regulation shall constitute a foul, and the player so offending shall throw the ball perpendicularly into the air to a height of at least 12 feet and the ball shall not be in play until it has touched the ground.

- When the ball passes out of bounds it is a foul, and the player causing it shall advance at right angles to the boundary line, 15 paces from the point where the ball went, and shall proceed as in rule 5.

- No tripping shall be allowed, nor shall any player use his hands to hold or push an adversary.

- The winner of the toss shall have the choice of the first goal, and the sides shall change goals after every successive inning. In starting the ball it shall be fairly kicked, not "babied", from a point 150 feet in front of the starter's goal.

- Until the ball is kicked no player on either side shall be in advance of a line parallel to the line of his goal and distant from it 150 feet.

- There shall be two judges, one from each of the contesting colleges, and one referee; all to be chosen by the captains.

- No player shall wear spikes or iron plates upon his shoes.

- In all matches a No. 6 ball shall be used, furnished by the challenging side and to become the property of the victor.

Though clearly much closer to soccer than to modern American football, at least one part of the modern game, the kickoff, is evident from rules eight and nine.

Harvard, which played a version more closely resembling the "Boston game" that allowed carrying of the ball, refused to attend this rules conference and continued to play under its own code. Harvard's voluntary absence from the meeting made it hard to get games against other American universities, so it agreed to play McGill University, from Montreal in a two-game series. The McGill team would travel to Cambridge to meet Harvard in a game played under "Boston" rules, followed by a game of rugby. On May 14, 1874, the first game, played under "Boston" rules was won easily by Harvard. The next day, the two teams played rugby to a scoreless tie, quite a feat considering that the Harvard team had never seen the game played before then.[5]

Harvard quickly took a liking to the rugby game, and its use of the touchdown, which until that time was not a type of scoring seen in American football. In the fall of 1874, the Harvard team traveled to Montreal to play McGill in rugby, and won by three touchdowns. On November 13, 1875, the first edition of The Game, the annual rivalry between Harvard and Yale was played under a modified set of rugby rules known as "The Concessionary Rules". Yale lost four to zero, but found that it too preferred the rugby style game. Spectators from Princeton carried the game back home, where it caught on there as well.[5]

On November 23, 1876, representatives from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia met at the Massasoit House in Springfield, Massachusetts to standardize a new code of rules based on the rugby game first introduced to Harvard by McGill University in 1874. The rules were based largely on the Rugby Union Code from England, though one important difference was the replacement of a kicked goal with a touchdown as the primary means of scoring. Three of the schools, Harvard, Columbia, and Princeton would form the Intercollegiate Football Association as a result of the meeting. Yale at first refused over a disagreement about the number of players per team; they would join the group in 1879.[2]

Walter Camp: Father of American football

Walter Camp is widely considered to be the most important figure in establishing the modern game of American football as a unique game apart from its soccer/rugby roots.[2][3][4] As a youth he excelled in many sports, from track and watersports, to baseball and soccer. In 1876, he enrolled at Yale where he excelled at several sports, earning varsity honors in every sport the school offered.[2]

Camp became a fixture at the Massasoit House "conventions" where rules were debated and changed. His first meeting came in 1878, where he proposed his first rule change: a reduction in team size from fifteen players to eleven. The motion was rejected. At the 1879 convention, he proposed that a safety should count as a score, and this proposal was rejected as well. In 1880, his first rule change, the establishment of eleven-a-side football, was passed. The effect was to open the game up and emphasize speed over strength. Also at the 1880 rules meeting, the rule that Camp is most famous for, the one that established the line of scrimmage and the snap from center to quarterback, was passed. Originally, the snap was executed with the foot of the center. Later changes made it possible to snap the ball with the hands, either through the air or by a direct hand-to-hand pass.[2]

Camp's new scrimmage rules revolutionized the game, though not always for the better. Princeton in particular would use scrimmage play to slow the game down, making incremental progress each down towards the end zone. Rather than increase scoring, which had been Camp's original intent behind the rule, it was being exploited to maintain control of the ball for the entire game, resulting in slow, unexciting contests. At the 1882 rules meeting, Camp proposed that a team be required to advance the ball a minimum of five yards within three downs. With the establishment of the line of scrimmage and the down-and-distance rules, the game was no longer either a modified form of rugby or a modified form of soccer, and American Football as a distinct sport was born.[2]

Camp was central to several more rule changes that are familiar as important aspects of American football. In 1881, the field was reduced in size to its modern dimensions of 120 yards by 53 1/3 yards. Several times in 1883, Camp tinkered with the scoring rules, finally arriving at awarding touchdowns four points, while kicks after touchdowns were worth two, safeties worth two, and field goals worth five. In 1887, the game timing was set as two halves of 45 minutes each. Also in 1887, two paid official per game, a referee and an umpire, were mandated. In 1888, rules were changed to allow tackling below the waist. In 1889, the officials were given whistles and stopwatches.[2]

After leaving Yale in 1882, Camp was employed by the New Haven Clock Company until his death in 1925. Though no longer a player, he remained a fixture at annual rules meetings for most of his life, and he personally selected an annual All-American team every year from 1898 through 1924. To this day, the Walter Camp Foundation continues to select All-American teams in his honor.[9]

Expansion of college football (1880–1904)

College football expanded greatly during the last two decades of the nineteenth century. In 1880, eight universities fielded intercollegiate teams.[10] By 1900, the number had expanded to 43.[11] Many major rivalries date from this time period, including Alabama-Auburn, Army-Navy, and Michigan-Ohio State.

In 1879, University of Michigan became the first team west of Pennsylvania to establish a college football team. Other Midwestern schools soon followed suit, including the University of Chicago, and The University of Minnesota. The Intercollegiate Conference of Faculty Representatives (also known as the Western Conference), precursor to the Big Ten Conference, was founded in 1895 as the nation's first college football league.[12]

Led by legendary coach Fielding Yost, Michigan became the first "western" national power by the turn of the twentieth century. From 1901-1905, Michigan had a 56 game undefeated streak that included the 1902 Rose Bowl game, a streak where Michigan scored 2,831 points while only allowing 40.[13] Another legendary coach spent most of his career in the Western Conference, Amos Alonzo Stagg of the University of Chicago. He coached first at the Springfield International YMCA Training School, then Chicago, and later at the University of the Pacific for a total of 57 years, to this day a record. As of 2007, he still ranked seventh on the list of winningest football coaches of all time with 314 wins. Ranked sixth on the same list, with 319 wins, is Glenn "Pop" Warner, who began is coaching career in 1895 with the University of Georgia.[14]

Violence and controversy (1905)

From its earliest days as a mob game, football was a violent sport.[5] The 1894 Harvard/Yale game, known as the "Hampden Park Blood Bath" resulted in four players receiving crippling injuries; the rivalry was suspended until 1897. The annual Army-Navy game was suspended from 1894-1898 for similar reasons.[15] One of the major problems was the popularity of mass-formations like the flying wedge where a large number of offensive players charged as a unit against a similarly arranged defense. The resultant collisions often led to serious injuries and death.[16]

The situation came to a head in 1905 when there were 19 fatalities nationwide. President Theodore Roosevelt threatened to shut the game down if drastic changes were not made. One rule change introduced in 1905, devised to open up the game and reduce injury, was the introduction of the legal forward pass. Though it would go under utilized for many years, this would prove to be the last and one of the most important rule changes in the establishment of the modern game.[17] 62 schools met in New York City on December 28, 1905 to discuss rule changes to make the game safer. As a result of this meeting, the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States, later named the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) was formed.[18]

Modernization and innovation (1906–1930)

After the 1905–1906 reforms, mass formation plays became illegal, the forward pass became legal, and several coaches emerged to take advantage of these sweeping changes that were introduced to the game. Amos Alonzo Stagg introduced such innovations as the huddle, the tackling dummy, and the pre-snap shift.[19] Other coaches, such as Pop Warner and Knute Rockne would make sweeping changes to the game's strategy that remain to this day.

Besides the coaching innovations, several rules changes during the first third of the twentieth century had a profound impact on the game, mostly in opening up the passing game. In 1914, the first roughing-the-passer rule was implemented. In 1918, the rules on eligible receivers were loosened.[20] Scoring rules also changed during this time, when field goals were lowered to three points each in 1909,[4] and touchdowns raised to six points each in 1912.[21]

Star players that emerged in the early twentieth century included Jim Thorpe, Red Grange, and Bronko Nagurski; these three would make the transition to the fledgling NFL and help turn it into a successful league. Sportswriter Grantland Rice helped popularize the sport with his poetic descriptions and colorful nicknames for the game's biggest players, including Grange, whom he dubbed "The Galloping Ghost," Notre Dame's "Four Horsemen" backfield, and Fordham University's "Seven Blocks of Granite".[22]

Pop Warner

Glenn "Pop" Warner coached at several schools throughout his career, including The University of Georgia, Cornell University, The University of Pittsburgh, Stanford University, Temple University.[23] He most famous stint was probably the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, where he coached Jim Thorpe, first president of the National Football League, Olympic Gold Medalist, and widely considered one of the best athletes in history.[24][25] Warner wrote one of the first important books of football strategy, Football for Coaches and Players. Though the shift was invented by Stagg, Warner's single wing and double wing formations utilized it to perfection; for almost 40 years these were the among most important formations in football. Out of the single and double wing formations, Warner was one of the first coaches to effectively utilize the forward pass. Among his other innovations to the game included modern blocking schemes, the three-point stance, and the reverse play.[23]

Knute Rockne

Knute Rockne rose to prominence in 1913 as an end for the University of Notre Dame, then a largely unknown midwestern Catholic school. When Army scheduled Notre Dame as a warm-up game, they thought little of the small school. Rockne and quarterback Gus Dorais made innovative use of the forward pass, still at that point a relatively unused weapon, to defeat Army 35-13 and help establish the school as national power. Rockne would return to coach the team in 1918, and devised the powerful Notre Dame Box offense, based on Warner's single wing. He is credited with opening up the game, being the first major coach to emphasize offense over defense. In 1927, his complex shifts led directly to a rule change whereby all offensive players had to stop for a full second before the ball could be snapped. Rather than simply a regional team, Rockne's Fighting Irish became famous for barnstorming, and would play any team in any location. It was during Rockne's tenure that the annual Notre Dame-University of Southern California rivalry began, one of the longest distance rivalries in the nation. He led his team to an impressive 105-12-5 record before his premature death by plane crash in 1931. So famous was he at that point that his funeral was broadcast nationally on radio.[23][26]

College football becomes dominant (1930–1958)

In the early 1930s, the college game blossomed in popularity. Bolstered by fierce rivalries such as the one between Alabama's Wallace Wade and Tennessee's General Robert Neyland, the college game grew in popularity in the south. While prior to the mid-1920s most national powers came from the northeast or the midwest, the situation changed when Wade's 1925 Alabama team won the 1926 Rose Bowl en route to its first national title. Lacking any major league sports presence, the game quickly became the south's most popular spectator sport.[27]

Several major modern college football conferences rose to prominence during this time period. The Southeastern Conference (SEC) formed in 1932 consisting mostly of schools in the Deep South.[28] The Southwest Athletic Conference had been founded in 1915. Consisting mostly of schools from Texas, the conference saw back-to-back national champions with Texas Christian University (TCU) in 1938 and Texas A&M in 1939.[29][30] The Pacific Coast Conference (PCC), a precursor to the Pacific Ten Conference (Pac-10), had its own back-to-back champion in the University of Southern California which was awarded the title in 1931 and 1932.[29] As in previous decades, the Big Ten continued to dominate in the 1930s and 1940's with Minnesota winning 5 titles between 1934 and 1941, and Michigan(1933 and 1948) and Ohio State (1942) also winning titles.[29][31]

National recognition of college football continued to grow in the 1930s, as it grew out of its regional affiliations. Four new bowl games were created: the Orange Bowl, Sugar Bowl, and the Sun Bowl in 1935, as well as the Cotton Bowl in 1937. In lieu of an actual national championship, these bowl games, along with the earlier Rose Bowl game, provided a way to match up teams from distant regions of the country that would not otherwise have played. In 1936, the Associated Press began its weekly poll of prominent sports writers, ranking all of the nation's college football teams. Since there was no national championship game, the final version of the AP poll was used to determine who would be crowned National Champion of college football.[32]

The 1930s saw growth in the passing game as well. Though General Neyland at Tennessee continued to eschew its use (former Tennessee quarterback Tex Davis noted, when told by Neyland that he would throw 20 or 30 times, "I didn't know he meant the whole season."[33]) several rules changes to the game had a profound effect on throwing the ball. In 1934, the rules committee removed two major penalties (a loss of five yards for a second incomplete pass in any series of downs and a loss of the possession for an incomplete pass in the end zone) and shrunk the circumference of the ball, making it easier to grip and throw. Players who became famous for taking advantage of the easier passing game included Alabama receiver Don Hutson and TCU passer "Slingin" Sammy Baugh.[34]

In 1935, New York City's Downtown Athletic Club awarded the first Heisman Trophy to Chicago halfback Jay Berwanger, who would also become the first ever NFL Draft pick in 1936. The trophy was designed by sculptor Frank Eliscu and modeled after NYU player Ed Smith. The trophy recognizes the nation's best college football player, and has become one of the most coveted awards in all of American sports. [35]

During World War II, many college football players enlisted in the armed forces. As most of these players had eligibility left on their college careers, many returned to college at West Point, bringing Army back-to-back national titles in 1944 and 1945 under coach Red Blaik. Doc Blanchard (known as Mr. Inside) and Glenn Davis (known as Mt. Outside) both won the Heisman Trophy, in 1945 and 1946 respectively. On the coaching staff of those 1944-1946 Army teams was future Pro Football Hall of Fame coach Vince Lombardi.[31][36]

The 1950s saw the rise of yet more dynasties and power programs. Oklahoma, under coach Bud Wilkinson, won three national (1950, 1955, 1956) and all ten Big Eight Conference championships in the decade while building a record 47 game winning streak that still stands today. Woody Hayes led Ohio State to two national titles, in 1954 and 1957, and dominated the Big Ten conference, winning more Big Ten titles (three) than any other school. Wilkinson and Hayes, along with Robert Neyland of Tennessee, oversaw a revival of the running game in the 1950s. Passing numbers dropped from an average of 18.9 attempts in 1951 to 13.6 attempts in 1955, while teams averaged just shy of 50 running plays per game. Nine out of ten Heisman trophy winners in the 1950s were runners. Notre Dame, one of the biggest passing teams of the decade, saw a substantial decline in success, the 1950s were the only decade between 1920 and 1990 when the team did not win at least a share of the national title. Paul Hornung, Notre Dame quarterback, did however win the Heisman in 1956, becoming the only player from a losing team to ever do so.[37][38]

Modern college football (1958–present)

Following huge television success of the National Football League's 1958 championship game, the college game would no longer enjoy the popularity of the NFL, at least on a national level. While both games benefited from the advent of television, and the college game continues to experience success and regional popularity to this day, it has not since topped the NFL in terms of national attention.[39][40][41]

As pro football became a national television phenomenon, college football did as well. In the 1950s, Notre Dame, which had a large national following, formed its own network to broadcast its games, but by and large the sport still retained a mostly regional following. In 1952, the NCAA claimed all television broadcasting rights for the games of its member institutions, and it alone negotiated television rights. This situation continued until 1984, when several schools brought suit under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act; the Supreme Court ruled against the NCAA and schools are now free to negotiate their own television deals. ABC Sports began broadcasting a national Game of the Week in 1966, bringing key matchups and rivalries to a national audience for the first time.[42]

New formations and play sets continued to be developed. Emory Bellard, an assistant coach under Darrell Royal at the University of Texas, developed a three-back option style offense known as the wishbone. The wishbone is a run-heavy offense that depends on the quarterback making last second decisions on when and to whom to hand or pitch the ball to. Royal went on to teach the offense to other coaches, including Bear Bryant at Alabama, Chuck Fairbanks at Oklahoma and Pepper Rodgers at UCLA; who all adapted and developed it to their own tastes.[43] The philosophical opposite of the wishbone is the spread offense, developed by many pro and college coaches throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Though some schools play a run-based version of the spread, its most common use is as a passing offense designed to "spread" the field both horizontally and vertically.[44]

Growth of bowl games

| Growth of bowl games 1930-2006[45] | |

| Year | # of games |

|---|---|

| 1930 | 1 |

| 1940 | 5 |

| 1950 | 8 |

| 1960 | 8 |

| 1970 | 8 |

| 1980 | 15 |

| 1990 | 19 |

| 2000 | 25 |

| 2006 | 32 |

In 1940, there had only been five bowl games (Rose, Orange, Sugar, Sun, and Cotton). By 1950, three more had joined that number. In 1970, there were still only eight. The number grew to eleven in 1976. At the birth of cable television and cable sports networks like ESPN, there were fifteen bowls in 1980. With greater national venues and increased available revenue, the bowls saw an explosive growth in numbers throughout the 1980s and 1990's. In the twenty years from 1960-1980, seven bowl games were added to the schedule. From 1980-2006 (the last completed season), an additional 17 bowl games were added to the schedule.[45][46] Some have criticized this growth, claiming that the increased number of games has diluted the significance of playing in a bowl game. Yet others have countered that the increased number of games has increased exposure and revenue for a greater number of schools, and see it as a positive development.[47]

With the growth of bowl games, it became difficult to determine a national champion in a fair and equitible manner. As conferences became contractually bound to certain bowl games (a situation known as a tie-in), match-ups that would guarantee a consensus national champion became increasingly rare. In 1992, seven conferences and independent Notre Dame formed the Bowl Coalition, which attempted to arrange an annual #1 versus #2 matchup based on the final AP poll standings. The Coalition lasted for 3 years, however the formula used to determine matchups was convoluted; tie-ins still took precedence in several cases. For example the Big Eight and SEC champions could never meet, since they were contractually bound to different bowl games. The coalition also excluded the Rose Bowl, arguably the most prestigious game in the nation, and two major conferences (the Pac-10 and Big Ten), meaning that it had limited success. In 1995, the Coalition was replaced by the Bowl Alliance, which reduced the number of bowl games to host a national champion to three (the Fiesta, Sugar, and Orange Bowls) and the participating conferences to five (the ACC, SEC, Southwest, Big Eight, and Big East). It was agreed that the #1 and #2 ranked teams would give up their prior bowl tie-ins and would be guaranteed to meet in the national championship game, which would rotate between the three participating bowls. The system still did not include the Big Ten, Pac-10, or the Rose Bowl, and thus still lacked the legitimacy that a true national championship would.[48][46]

Bowl Championship Series

In 1998, a new system was put into place, the Bowl Championship Series. For the first time, it included all major conferences (ACC, Big East, Big 12, Big Ten, Pac-10, and SEC) and all four major bowl games (Rose, Orange, Sugar and Fiesta). The champions of these 6 conferences, along with two "at-large" selections, were invited to play in the 4 bowl games. Each year, one of the four bowl games would serve as a national championship game. Also, a complex system of human polls, computer rankings, and strength of schedule calculations was instituted to rank schools. Based on this ranking system, the #1 and #2 teams would meet each year in the national championship game. Traditional tie-ins were maintained for schools and bowls not part of the national championship. For example, in years when not part of the national championship, the Rose Bowl would still host the Big Ten and Pac-10 champions.[48]

The system continued to change, as the formula for ranking teams was tweaked from year to year. At-large teams could be chosen from any of the Division I conferences, though only one selection, Utah in 2005, came from a non-BCS affiliated conference. Starting with the 2006 season, a fifth game, simply called the BCS National Championship Game was added to the schedule, to be played at the site of one of the four BCS bowl games on a rotating basis, one week after the regular bowl game. This opened up the BCS to two additional at-large teams. Also, rules were changed to add the champions of five additional conferences (Conference USA, the Mid-American Conference, the Mountain West Conference, the Sun Belt Conference and the Western Athletic Conference) provided that said champion ranked in the top twelve in the final BCS rankings.[48]

Professional football

Birth of professional football (1892)

Football caught on among the general population and began to be the subject of intense competition and rivalry, albeit of a localized nature. Although payments to players were considered unsporting and dishonorable at the time, a Pittsburgh area club, the Allegheny Athletic Association, surreptitiously hired former Yale All-American guard William "Pudge" Heffelfinger. On November 12, 1892, Heffelfinger became the first known professional football player. He was paid $500 to play in a game against the Pittsburgh Athletic Club. Heffelfinger picked up a Pittsburgh fumble and ran 35 yards for a touchdown, winning the game 4-0 for Allegheny. Although many observers held suspicions, the payment remained a secret for many years.[49][50][3][4]

On September 3, 1895 the first wholly professional game was played, in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, between the Latrobe YMCA and the Jeannette Athletic Club. Latrobe won the contest 12-0.[3][4]

Early professional teams (1897–1919)

In 1897, the Latrobe Athletic Association paid all of its players for the whole season, becoming the first fully professional football team. In 1899, the Morgan Athletic Club, on the southside of Chicago, was founded. This team later became the Chicago Cardinals, and now is known as the Arizona Cardinals, making them the oldest continuously operating professional football team.[4]

The first known professional football league, known as the National Football League (not the same as the modern league) began play in 1902 with teams from the Mid Atlantic. Several baseball clubs formed football teams to play in the league, including the Philadelphia Athletics and the Philadelphia Phillies. A five-team tournament, known as the World Series of Football was organized by the league. The league and the World Series only lasted two seasons.[4]

The game moved west into Ohio which became the center of professional football during the early decades of the twentieth century. Small towns such as Massillon, Akron, Portsmouth, and Canton all supported pro teams. In 1915, the Canton Bulldogs signed former Olympian and Carlisle Indian School standout Jim Thorpe to a pro contract. Thorpe would become the face of pro football for the next several years, and would be present at the founding of the National Football League five years later.[4][51]

Early years of the NFL (1920–1945)

Formation

In 1920, the first pro league, the American Professional Football Association, was founded, in a meeting at a Hupmobile car dealership in Canton, Ohio. Jim Thorpe was elected the league's first president. After several more meetings, the league's membership was formalized. The original teams were:[21][52]

- Akron Pros

- Buffalo All-Americans

- Canton Bulldogs

- Chicago Tigers

- Cleveland Indians

- Columbus Panhandles

- Dayton Triangles

- Decatur Staleys

- Detroit Heralds

- Hammond Pros

- Muncie Flyers

- Racine Cardinals

- Rochester Jeffersons

- Rock Island Independents

The league in its early years was little more than a formal agreement to play each other and to declare a champion at season's end. Teams were still permitted to play non-league members. The 1920 season saw several teams drop out and fail to play through their schedule. Only four teams: Akron, Buffalo, Canton, and Decatur, finished the schedule. Akron claimed the first league champion, with the only undefeated record among the remaining teams.[21][53]

Growth of the NFL

In 1921, several more teams joined the league, increasing the membership to 22 teams. Among the new additions were the Green Bay Packers, which are the only team in the NFL with the same name and home city that remains from that year. Also in 1921, A.E. Staley, the owner of the Decatur Staleys, sold the team to player-coach George Halas, who would go on to become one of the most important figures in the first half century of the NFL. In 1922, Halas would move the team to Chicago and rename it the Chicago Bears.[54] [55]

By the mid 1920's, the NFL membership had grown to 25 teams, and a rival league known as the American Football League was formed. The rival AFL would fold after a single season, but it symbolized a growing interest in the professional game. Several college stars joined the NFL, most notably Red Grange from the University of Illinois, who was taken on a famous barnstorming tour in 1925 by the Chicago Bears.[56][54]

The 1932 NFL playoff game

In the 1932 season, the Chicago Bears and the Portsmouth Spartans tied with the best regular-season records. To determine the champion, the league voted to hold their first playoff game. Because of very cold weather, the game was held indoors at Chicago Stadium, which forced some temporary rule changes. Chicago won, 9-0. The playoff proved so popular that the league reorganized into two divisions for the 1933 season, with the winners advancing to a scheduled championship game. A number of new rule changes were also instituted: the goal posts were moved forward to the goal line, every play started from between the hash marks, and forward passes could originate from anywhere behind the line of scrimmage (instead of the previous five yards behind).[57][58][59] In 1936, the NFL instituted the first ever draft of college players. The first selection was Heisman Trophy winner Jay Berwanger; he declined to play professional football.[60]Also in that year, another AFL formed, it would last only 2 seasons.[61]

The war years

In 1941, the NFL named its first Commissioner in 1941, Elmer Layden who moved the league headquarters to Chicago. The new office replaced the office of President. Layden would hold the job for 5 years, before being replaced by Pittsburg Steelers co-owner Bert Bell in 1946, who himself moved the league headquarters to Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia.[62]

During World War II, a player shortage led to a shrinking of the league as several teams folded, and others merged. Among the short-lived merged teams were the Steagles (Pittsburgh and Philadelphia) in 1943, the Carpets (Chicago Cardinals and Pittsburgh) in 1944, and a team formed from the merger of the Brooklyn Dodgers and Boston Yanks in 1945. [52] [62]

Stability and growth of the NFL (1946–1957)

1946 was an important year in the history of the professional football. Bert Bell became commissioner of the NFL, providing a stable source of leadership for the next 13 years.[62][63] Before he became commissioner, league membership was fluid. Between 1920 and 1945, 53 teams had gone defunct.[52] In 1946, the NFL had ten teams, nine which are still in operation today.[64] The league also integrated in 1946, when the Los Angeles Rams signed two African American players, Kenny Washington and Woody Strode. Also in that same year, a competing league, the All-America Football Conference (AAFC), began operation.[62]

In 1950, the AAFC folded, and three teams from that league were absorbed into the NFL, the Cleveland Browns (who had won the AAFC Championship every year of the league's existence), the San Francisco 49ers, and the Baltimore Colts (not the same as the modern franchise, this version folded after one year). The remaining players were chosen by the now 13 NFL teams in a dispersal draft. Also in 1950, the Los Angeles Rams became the first team to televise its entire schedule, marking the beginning of an important relationship between television and professional football.[62] 1951 marked the birth of the modern Pro Bowl all-star football game, and for the first time the NFL Championship game was televised nationally, on the DuMont Television Network. In 1952, the Dallas Texans went defunct, becoming the last ever NFL franchise to do so.[52] In 1953, a new Baltimore Colts franchise formed to take over the assets of the Texans. The player's union, known as the NFL Players Association formed in 1956.[65]

NFL supremacy (1958–present)

The Greatest Game Ever Played

At the conclusion of the 1958 NFL season, the Baltimore Colts and the New York Giants met in Yankee Stadium to determine the league champion. Tied after 60 minutes of play, it became the first NFL game to go into sudden death overtime. The final score was Baltimore Colts 23, New York Giants 17. The game has since become widely known as The Greatest Game Ever Played. The game was carried live on the NBC television network, and the national exposure it provided the league has been cited as a watershed moment in professional football history. Many analyses cite this game as one of the key factors in making the NFL one of the most popular sports leagues in the United States.[66][65][67]Journalist Tex Maule said of the contest, "This, for the first time, was a truly epic game which inflamed the imagination of a national audience."[68]

The American Football League and merger

In 1959, longtime NFL commissioner Bert Bell died of a heart attack while attending an Eagles/Steelers game at Franklin Field. That same year, Dallas, Texas businessman Lamar Hunt led the formation of the rival American Football League, the fourth such league to bear that name. Unlike the earlier rival leagues, and bolstered by television exposure, the AFL posed a significant threat to NFL dominance of the professional football world. With the exception of Los Angeles and New York, the AFL avoided placing teams in markets where they would directly compete with established NFL franchises. In 1960, the AFL began play with eight teams, and new NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle took office.[65]

The AFL became a viable alternative to the NFL as it made a concerted effort to poach established talent from the NFL, and worked hard to secure top college players. Led by Oakland Raiders owner and AFL commissioner Al Davis, the AFL established a "war chest" to entice top talent with higher pay than they would get from the NFL. Former Green Bay Packers quarterback Babe Parilli would become a star for the Boston Patriots during the early years of the AFL, and University of Alabama passer Joe Namath would eschew the NFL to play for the New York Jets. Namath would become the face of the league as it reached its height of popularity in the mid 1960's. Davis's methods worked, and in 1966, the junior league forced a partial merger with the NFL, when it was agreed that the two leagues would have a common draft and play in a common season ending championship game, known as the AFL-NFL World Championship. Two years later, it would change its name to the Super Bowl. [69] [70][71]

The NFL won the first two Super Bowls handily, and it looked as though the younger AFL was outclassed. Following the 1968 season, Super Bowl III proved to be the turning point in the AFL's fortunes. The heavily favored Baltimore Colts lost to the New York Jets and Joe Namath, cementing the AFL's places as equal in stature to the NFL. In 1970, the two leagues merged to form a new 26-team league.[69]

The modern NFL

The NFL continued to grow throughout the 1970's until today, expanding several times to its current 32-team membership. The Super Bowl game has become more than simply a football championship. Annually ranked as the one of the top televised events in the United States, it has become a major source of advertising revenue for the major television networks that have carried it and it serves as a means for advertisers to debut elaborate and expensive commercials for many products.[72] The NFL has grown to become the most popular spectator sports league in the United States.[73]

Several other rival leagues would be formed during this time period, though none would have the success of the AFL. In 1974, the World Football League formed, and despite attracting such stars as Larry Czonka away from the NFL with lucrative contracts, the league was financially insolvent and folded after only 2 seasons. In 1982, the United States Football League formed as a spring league, and enjoyed moderate success during its first two seasons behind such stars as Jim Kelly and Herschel Walker. It moved its schedule to the fall in 1985, and tried to compete with the NFL directly. It couldn't, and it folded, despite winning an anti-trust suit against the older league. In 2001, the XFL was formed as a joint venture between the World Wrestling Federation and the NBC television network. It folded after one season, and XFL stars such as Tommy Maddox and Rod "He Hate Me" Smart enjoyed limited success in the NFL. [74][75][76]

The NFL founded a developmental league known as the World League of American Football with teams based in the United States, Canada, and Europe. The WLAF ran for two years, from 1991–1992. The league went on a two-year hiatus before reorganizing as NFL Europe in 1995, with teams only in European cities. The name of the league was changed to NFL Europa in 2006. After the 2007 season, the NFL announced that it was closing down the league to focus its international marketing efforts in other ways, such as playing NFL regular season games in cities outside of the U.S.[77]

Other similar codes of football

There are other codes of football that share a common history with American football. Canadian football is a form of the game that evolved parallel to American football. While both games share a common history, there are some important differences between the two.[78] A more modern sport that derives from American football is Arena football, designed to be played indoors inside of hockey or basketball arenas. The game was invented in 1981 by Jim Foster and the Arena Football League was founded in 1987 as the first major professional league to play the sport. Several other indoor football leagues have since been founded and continue to play today.[79]

American football's parent sport of rugby continued to evolve. Today, two distinct codes of rugby, known as rugby union and rugby league are played. Since the two codes split in 1895, the history of rugby league and the history of rugby union have evolved separately.[80]

See also

- Comparison of Canadian and American football

- Comparison of American football and rugby league

- Comparison of American football and rugby union

- History of soccer

- Football (ball)

References

- Bennett, Tom (1976). The Pro Style: The Complete Guide to Understanding National Football League Strategy. Los Angeles: National Football League Properties, Inc., Creative Services Division.

- McCambridge, Michael (Ed.) (1999). ESPN SportsCentury. New York: Hyperion Books. ISBN 0-7868-6471-0.

- Peretz, Howard (1999). It Ain't Over 'Til The Fat Lady Sings: The 100 Greatest Sports Finishes of All Time. New York: Barnes and Noble Books. ISBN 0-76071-7079.

- Vancil, Mark (Ed.) (2000). ABC Sports College Football All-Time All-America Team. New York: Hyperion Books. ISBN 0-7868-6710-8.

Notes

- ^ National Football League, "NFL:America's Choice," January 2007, http://www.coldhardfootballfacts.com/Documents/NFL_all_about_SB_1-07.pdf

- ^ a b c d e f g "Camp and His Followers: American Football 1876-1889". THE JOURNEY TO CAMP: The Origins of American Football to 1889. Professional Football Researchers Association. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ a b c d e f "The History of Football". The History of Sports. Saperecom. 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "NFL History 1869-1910". NFL.com. NFL Enterprises LLC. 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "No Christian End!". THE JOURNEY TO CAMP: The Origins of American Football to 1889. Professional Football Researchers Association. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ Meacham, Scott (2006). "Old Division Football, The Indigenous Mob Soccer Of Dartmouth College (pdf)" (PDF). dartmo.com. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ Allaway, Roger (2001). "Were the Oneidas playing soccer or not?". The USA Soccer History Archives. Dave Litterer. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ^ "1800s". Rutgers Through The Years. Rutgers University. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ "Walter Camp : 1859 - 1925". Walter Camp History Page. The Walter Camp Foundation. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ "1880 season". Dolphin Historical Football Ratings. Dolphin Sim. 2005. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ^ "1900 season". Dolphin Historical Football Ratings. Dolphin Sim. 2005. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ^ "Big Ten History". Big Ten Conference - Official Athletic Site -Traditions. 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ^ Vancil (2000), pp 16

- ^ Nance, Roscoe (April 4, 2007). "Legendary Grambling coach Eddie Robinson dies". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2007-05-19. - A chart near the bottom of the article lists the top 10 winningest coaches of all time.

- ^ Vancil (2000), pp 16-18

- ^ Bennett (1976), pp 20

- ^ Vancil (2000), pp 18

- ^ "The History of the NCAA". NCAA.org. National Collegiate Athletic Association. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ^ Vancil (2000), pp 17

- ^ Vancil (2000) pp 22

- ^ a b c "NFL History 1911-1920". NFL.com. NFL Enterprises LLC. 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ^ Vancil (2000) pp 24

- ^ a b c Bennett (1976), pp 20-21

- ^ "ESPN.com: Top N. American athletes of the century". ESPN.com. 2001. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ^ Vancil (2000), pp 20

- ^ Vancil (2000), pp 19-22

- ^ Vancil (2000), pp 24-29

- ^ Ours, Robert M. (2007). "Southeastern Conference". College Football Encyclopedia. Augusta Computer Services. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ a b c McCambridge (1999), pp 124

- ^ "A Look Back at the Southwest Conference". 2006-2007 Texas Almanac. The Dallas Morning News. 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ a b McCambridge (1999), pp 148

- ^ Vancil (2000), pp 30

- ^ Vancil 2000, pp 29

- ^ Vancil (2000), pp 28-30

- ^ "A Brief History of the Heisman Trophy". Heisman Trophy. heisman.com. 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ Vancil (2000), pp 39

- ^ Vancil (2000), pp 41-45

- ^ McCambridge (1999) pp 172

- ^ McCambridge (1999), pp 171

- ^ Bennett (1976) pp 56

- ^ Barnidge, Tom (2000). "1958 Colts remember the 'Greatest Game'". nfl.com. Retrieved 2007-03-21. reprinted from Official Super Bowl XXXIII Game Program.

- ^ Vancil (2000) pp 46-48

- ^ Vancil (2000), pp 56

- ^ Bennett (1976), Appendix pp 209-217

- ^ a b Call, Jeff (December 20, 2006). "Changing seasons". Deseret News (Salt Lake City). republished in FindArticles.com. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "College Bowl Games". Hickok Sports. 2006. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- ^ Celezic, Mike (December 9, 2006). "Too many bowl games? Nonsense". MSNBC. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c "BCS Chronology". FOX Sports on MSN. 2006. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- ^ "History:The Birth of Pro Football". Pro Football Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ "Heffelfinger, "Pudge" (William W.)". Sports Biographies. HickokSports.com. 2004. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ Bennett (1976), pp 22

- ^ a b c d Hickock, Ralph (2004). "NFL Franchise Chronology". HickokSports.com. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ Bennett (1976), pp 22-23

- ^ a b "NFL History 1921-1930". NFL.com. NFL Enterprises LLC. 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ Bennett (1976), pp 23-24

- ^ Bennett (1976), pp 25-26

- ^ "December 18, 1932". This Date in NFL History. NFL Enterprises LLC. 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ Hickock, Ralph (2004). "The 1932 NFL Championship Game". HickokSports.com. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ Bennett (1976), pp 32-33

- ^ Bennett (1976), pp 35

- ^ "NFL History 1931-1940". NFL.com. NFL Enterprises LLC. 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ a b c d e "NFL History 1941-1950". NFL.com. NFL Enterprises LLC. 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ "Bert Bell 1946-1959". Sports e-cyclopedia. Tank Productions. 2002. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ "1946 NFL Standings". Football@JT-SW.com. John Troan. 2002. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ a b c "NFL History 1951-1960". NFL.com. NFL Enterprises LLC. 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ Barnidge, Tom. "1958 Colts remember the 'Greatest Game'". nfl.com, reprinted from Official Super Bowl XXXIII Game Program. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ Peretz (1999), pp 58-59

- ^ MacCambridge (1999), pp 171

- ^ a b "NFL History 1961-1970". NFL.com. NFL Enterprises LLC. 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ "Remember the AFL". American Football League Hall of Fame. 2003. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ "History of the Super Bowl". SuperNFL.com. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ La Monica, Paul R. (2007). "Super prices for Super Bowl ads". CNN Money. Cable News Network LP, LLLP. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ "NFL Sets Paid Attendance Record". NFL.com. NFL Enterprises LLC. 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ "NFL History 1971-1980". NFL.com. NFL Enterprises LLC. 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ "History of the USFL". Our Sports Central. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ Boehlert, Eric (2001). "XFL makes history!". Salon Arts and Entertainment. Salon.com. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ "NFL Europe homepage". World League Licensing LLC. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ^ "A BRIEF HISTORY OF FOOTBALL CANADA". Football Canada. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ^ "History of Arena Football". HickokSports.com. 2006. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ^ Fagan, Sean (2004). "The Rugby Divide of 1895". RL1895.com. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

Further reading

- Fox, Stephen (1998). Big Leagues: Professional Baseball, Football, and Basketball in National Memory. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0688093000.

- MacCambridge, Michael (Ed.) (2005). ESPN College Football Encyclopedia: The Complete History of the Game. New York: Hyperion Books. ISBN 1401337031.

- Perrin, Tom (1987). Football: A College History. McFarland & Co Inc. ISBN 0899502946.

- Smith, Ronald A. (1988). Sports and Freedom: The Rise of Big-Time College Athletics. Oxford University Press =. ISBN 0195065824.

- Watterson, John Sayle (2000). College Football: History, Spectacle, Controversy. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6428-3.

- Whittingham, Richard (2003). Sunday's Heroes. Chicago: Triumph Books. ISBN 1-57243-517-8.