Harry Houdini

Harry Houdini | |

|---|---|

Harry Houdini became world-renowned for his stunts and feats of escapology even more than for his magical illusions. | |

| Born | March 24, 1874 |

| Died | October 31, 1926 (aged 52) |

| Occupation(s) | magician, escapologist, stunt performer, actor, historian, pilot, and paranormal investigator. |

Harry Houdini (March 24, 1874 – October 311926), whose real name was Ehrich Weiss (which was changed from Erich Weisz when he emigrated to America), was a Hungarian-born American magician, escapologist (widely regarded as one of the greatest ever), stunt performer, as well as an investigator of spiritualists, film producer, actor, and an amateur aviator.

Biography

Birth

Harry Houdini was born into a Jewish family in Budapest, Hungary. His given name is found spelled differently in different sources and also his birth date is uncertain. However, years after his death a copy of his birth certificate was found and published in The Houdini Birth Research Committee's Report (1972). According to that original source, he was born on March 24, 1874 as Erich Weisz. Houdini himself spelled his name Ehrich Weiss, as can be seen from this letter to his mother. As to his birth date, from 1900 onwards Houdini claimed in interviews to have been born in Appleton, Wisconsin on April 6, 1874.

Houdini's father, Mayer (Mayo) Samuel Weiss (1829-1892), also known as Samuel Mayer Weisz, was a rabbi; and his mother was Cecilia Steiner (1841-1913). Ehrich had six siblings: Herman M. Weiss (half-brother) (1863-1885); Nathan J. Weiss (1870-1927); Gottfried William Weiss (1872-1925); Theodore Weiss (Dash) (1876-1945); Leopold D. Weiss (1879-1962); and Gladys Carrie Weiss (1882-?).

He immigrated with his family to the United States on July 3, 1878 at the age of four on the SS Fresia with his mother (who was pregnant), and his four brothers. Houdini's name was listed as Ehrich Weiss.[1] Friends called him "Ehrie" or "Harry".

At first, they lived in Appleton, where his father served as rabbi of the Zion Reform Jewish Congregation. In 1880, the family was living on Appleton Street.[2] On June 6, 1882, Rabbi Weiss became an American citizen. After losing his tenure, he moved to New York City with Ehrich in 1887. They lived in a boarding house on East 79th Street. Rabbi Weiss later was joined by the rest of the family once he found more permanent housing. As a child Ehrich took several jobs, and then became a champion cross country runner. He made his public debut as a 10-year-old trapeze artist, calling himself, "Ehrich, the prince of the air."

Magic career

In 1894, Weiss became a professional magician, and began calling himself "Harry Houdini" because he was influenced by French magician Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin and his friend Jack Hayman told him that in French adding an "i" to Houdin would mean "like Houdin" the great magician. In later life Houdini would claim that the first part of his new name, Harry, was a homage to Harry Kellar, whom Houdini admired a great deal. However, it's more likely Harry derived naturally from his nickname "Ehrie."

Initially, his magic career resulted in little success. He performed in Dime Museums and sideshows, and even doubled as "the Wild Man" at a circus. Houdini initially focused on traditional card tricks. At one point he billed himself as the "King of Cards." But he soon began experimenting with escape acts. In 1893, while performing with his brother "Dash" in Coney Island as "The Brothers Houdini", Harry met and married fellow performer Wilhelmina Beatrice (Bess) Rahner. Bess replaced Dash in the act which became known as "The Houdinis." For the rest of his performing career, Bess would work as his stage assistant.

Harry Houdini's "big break" came in 1899 when he met manager Martin Beck. Impressed by Houdini's handcuffs act, Beck advised him to concentrate on escape acts and booked him on the Orpheum vaudeville circuit. Within months, he was performing at the top vaudeville houses in the country. In 1900, Beck arranged for Houdini to tour Europe.

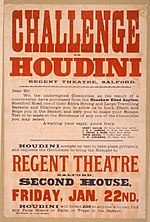

Houdini was a sensation in Europe where he became widely known as "The Handcuff King." He toured England, Scotland, the Netherlands, Germany, France, and Russia. In each city Houdini would challenge local police to restrain him with shackles and lock him in their jails. In many of these challenge escapes, Houdini would first be stripped nude and searched. In Moscow, Houdini escaped from a Siberian prison transport van. Publicity stated that, had he been unable to free himself, he would have had to travel to Siberia where the only key was kept. In Cologne, he sued a police officer, Werner Graff, who claimed he made his escapes via bribery.[3] Houdini won the case when he opened the judge's safe (he would later say the judge had forgotten to lock it). With his newfound wealth and success, Houdini purchased a dress said to have been made for Queen Victoria. He then arranged a grand reception where he presented his mother in the dress to all their relatives. Houdini said it was the happiest day of his life. In 1904, Houdini returned to the U.S. and purchased a house for $25,000, a brownstone at 278 W. 113th Street in Harlem, New York.[4] The house still stands today.

From 1907 and throughout the 1910s, Houdini performed with great success in the United States. He would free himself from jails, handcuffs, chains, ropes, and straitjackets, often while hanging from a rope in plain sight of street audiences. Because of imitators and a dwindling audience, on January 25, 1908, Houdini put his "handcuff act" behind him and began escaping from a locked, water-filled milk can. The possibility of failure and death thrilled his audiences. Houdini also expanded his challenge escape act -- in which he invited the public to devise contraptions to hold him -- to included nailed packing crates (sometimes lowered into the water), riveted boilers, wet-sheets, mailbags, and even the belly of a whale that washed ashore in Boston. At one point, brewers challenged Houdini to escape from his Milk Can after they filled it with beer. Many of these challenges were pre-arranged with local merchants in what is certainly one of the first uses of mass tie-in marketing. Rather than promote the idea that he was assisted by spirits, as did the Davenport Brothers and others, Houdini's advertisements showed him making his escapes via dematerializing[5], although Houdini himself never claimed to have supernatural powers.

In 1912, Houdini introduced perhaps his most famous act, the Chinese Water Torture Cell, in which he was suspended upside-down in a locked glass-and-steel cabinet full to overflowing with water. The act required that Houdini hold his breath for more than three minutes. Houdini performed the escape for the rest of his career. Despite two Hollywood movies depicting Houdini dying in the Torture Cell, the escape had nothing to do with his demise.

Houdini explained some of his tricks in books written for the magic brotherhood throughout his career. In Handcuff Secrets (1909) he revealed how many locks and handcuffs could be opened with properly applied force, others with shoestrings. Other times, he carried concealed lockpicks or keys, being able to regurgitate small keys at will. When tied down in ropes or straitjackets, he gained wiggle room by enlarging his shoulders and chest, and by moving his arms slightly away from his body, and then dislocating his shoulders. His straitjacket escape was originally performed behind curtains, with him popping out free at the end. However, Houdini's brother who was also an escape artist billing himself as Theodore Hardeen, after being accused of having someone sneak in and let him out and being challenged to escape without the curtain, discovered that audiences were more impressed and entertained when the curtains were eliminated, so that they could watch him struggle to get out. They both performed straitjacket escapes dangling upside-down from the roof of a building for publicity on more than one occasion. It is said that Hardeen once handed out bills for his show while Houdini was doing his suspended straightjacket escape and Houdini became upset because people thought it was Hardeen up there escaping, not Houdini. Many people imitate some of his tricks to this day.

For the majority of his career, Houdini performed his act as a headliner in vaudeville. For many years he was the highest paid performer in American vaudeville. One of Houdini's most notable non-escape stage illusions was performed at New York's Hippodrome Theater when he vanished a full-grown elephant (with its trainer) from a stage, beneath which was a swimming pool. In 1923, Houdini became president of Martinka & Co., America's oldest magic company. The business is still in operation today. In the final years of his life (1925/26), Houdini launched his own full evening show which he billed as "3 Shows in One: Magic, Escapes, and Fraud Mediums Exposed."

Notable escapes

- The Mirror challenge

In 1904 Houdini was challenged by the London Daily Mirror newspaper to escape from a special handcuff that it claimed has taken a Birmingham locksmith five years to make. Houdini accepted the challenge for March 17 during a matinee performance at London's Hippodrome theater. It was reported that 4000 people and over 100 journalists turned out for the much hyped event. The escape attempt dragged on for over an hour, during which Houdini emerged from his "ghost house" (a small screen used to concealed the method of his escape) several times. On one occasion he asked if the cuff could be removed so he could take off his coat. The Mirror representative, Frank Parker, refused, saying Houdini could gain an advantage if he saw how the cuff was unlocked. Houdini promptly took out a pen-knife and used it to cut his coat from his body. After an hour and ten minutes, Houdini emerged free. As he was paraded on the shoulders of the cheering crowd he broke down and wept. Houdini later said it was the most difficult escape of his career.

After Houdini's death, his friend Will Goldstone published in his book Sensational Tales of Mystery Men that Houdini was bested that day and appealed to his wife, Bess, for help. Goldstone goes on to claim that Bess begged the key from the Mirror representative which she then slipped to Houdini in a glass of water.

Goldstone offered no proof of his account, and many modern biographers have found evidence (notably in the custom design of the handcuff itself) that the entire Mirror challenge was pre-arranged by Houdini and the newspaper, and that his long struggle to escape was pure showmanship.[6]

- The Milk Can

In 1908 Houdini introduced his original invention, the Milk Can escape. In this effect, Houdini would be handcuffed and sealed inside an over-sized Milk Can filled with water and make his escape behind a curtain. As part of the effect, Houdini would invite members of the audience to hold their breath along with him while he was inside the can. Advertised with dramatic posters that proclaimed "Failure Means A Drowning Death", the escape proved to be a sensation. Houdini soon modified the escape to include the Milk Can being locked inside a wooden chest. Houdini only performed the Milk Can escape as a regular part of his act for four years, but it remains one of the effects most associated with the escape artist. Houdini's brother, Theo. Hardeen, continued to perform the Milk Can (and the wooden chest variation) into the 1940s.

- The Chinese Water Torture Cell

Due to the vast amounts of imitators of his Milk Can escape, in 1911 Houdini replaced the Milk Can with his most famous escape: The Chinese Water Torture Cell. In this escape, Houdini's feet would be locked in stocks and he'd be lowered upside down into a tank filled with water. The mahogany and metal cell featured a glass front where audiences could clearly see Houdini. The stocks would be locked to the top of the cell and curtain would conceal his escape. In the earliest version of the Torture Cell, a metal cage was lowered into the cell and Houdini was enclosed inside that. While making the escape more difficult (the cage prevented Houdini from turning), the cage bars also offered protection should the glass front break.

The original cell was built in England where Houdini first performed the escape for an audience of one person as part of a one-act play he called "Houdini Upside Down." This was so he could copyright the effect and have grounds to sue imitators (which he did). While the escape was advertised as "The Chinese Water Torture Cell" or "The Water Torture Cell", Houdini always referred to it as "the Upside Down" or "USD." The first public performance of the USD was at the Circus Busch in Berlin, Germany, on September 21, 1912. Houdini continued to perform the escape until his death in 1926. Despite two Hollywood movies depicting Houdini dying in the Torture Cell, the escape had nothing to do with his demise.[7]

- Suspended straight jacket escape

One of Houdini's most popular publicity stunts was to have himself strapped into a regulation straight jacket and suspended by his ankles from a tall building or crane. Houdini would then make his escape in full view of the assembled crowd. In many cases, Houdini would draw thousands of onlookers who would chock the street and bring city traffic to a halt. Houdini would sometimes ensure press coverage by performing the escape from the office building of a local newspaper. In New York City, Houdini performed the suspended straight jacket escape from a crane being used to build the New York subway. Film footage of Houdini performing the escape in Dayton, Ohio exists in The Library of Congress.

Pioneer aviator

In 1909 Houdini become fascinated with aviation. That same year he purchased a French Voisin biplane for $5000 and hired a full-time mechanic, Antonio Brassac. Houdini painted his name in bold block-letters on the Voisin's sidepannels and tail. After crashing once, Houdini made his first successful flight on November 26 in Hamburg, Germany.

In 1910, Houdini toured Australia. He brought with him his Voisin biplane and had the distinction of achieving the first controlled powered flight over Australia, doing so on March 21, at Diggers Rest, Victoria, just north of Melbourne. [2]. Colin Defries preceded him, but he crashed the plane on landing. [3]. To reporters, Houdini proudly claimed that the while the world may forget about him as a magician and escape artist, they would never forget Houdini the pioneer aviator.

After his Australia tour, Houdini put the Voisin into storage in England. Although he announced he would use it to fly from city to city during his next Music Hall tour, Houdini never flew again.[8]

Movie career

Houdini made his first movie for Pathé in 1901. Titled Merveilleux Exploits du Célébre Houdini à Paris it featured a loose narrative meant to showcase several of Houdini's famous escapes, including his straight-jacket escape. Houdini returned to film in 1916 when he served as special effects consultant on the Pathé thriller, The Mysteries of Myra. That same year he got an offer to star as Captain Nemo in a silent version of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, but the project never made it into production.[9]

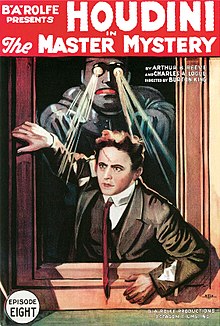

In 1918, Houdini signed a contract with film producer B.A. Rolfe to star in a fifteen part serial The Master Mystery (released in January 1919). As was common at the time, the film serial was released simultaneously with a novel. Financial difficulties resulted in B.A. Rolfe Productions going out of business, but The Master Mystery was a box-office success and lead to Houdini being signed by Famous Players-Lasky Corporation/Paramount Pictures for whom he made two pictures, The Grim Game (1919) and Terror Island (1920). While filming an aerial stunt for The Grim Game, two bi-planes collided in mid-air with a stuntman doubling Houdini dangling by a rope from one of the planes. Publicity was geared heavily toward promoting this dramatic "caught on film" moment, claiming it was Houdini himself dangling from the plane. While filming these movies in Los Angeles, Houdini rented a home in Laurel Canyon.

Following his two-picture stint in Hollywood, Houdini returned to New York and started his own film production company called the "Houdini Picture Corporation." He produced and starred in two films, The Man From Beyond (1921) and Haldane of the Secret Service (1923). He also started up his own film laboratory business called The Film Development Corporation (FDC), gambling on a new process for developing motion picture film. Houdini’s brother, Hardeen, left his own career as a magician and escape artist to run the company. Magician Harry Keller was a major investor.[10]

Neither Houdini's acting career nor film development corporation found success, and he gave up on the movie business in 1923, complaining that "the profits are too meager.” But his celebrity was such that years later he would be given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (at 7001 Hollywood Blvd).

Of all Houdini's movies, only The Man From Beyond has been commercially released on DVD. Incomplete versions of The Master Mystery and Terror Island were released by private collectors on VHS. Complete 35 mm prints of Haldane of the Secret Service and The Grim Game exist only in private collections. Haldane of the Secret Service was screened in Los Angeles in 2007.[11]

Debunking spiritualists

In the 1920s, after the death of his beloved mother, Cecilia, he turned his energies toward debunking self-proclaimed psychics and mediums, a pursuit that would inspire and be followed by later-day conjurers Milbourne Christopher, James Randi, Martin Gardner, P.C. Sorcar and Penn and Teller. Houdini's magical training allowed him to expose frauds who had successfully fooled many scientists and academics. He was a member of a Scientific American committee which offered a cash prize to any medium who could successfully demonstrate supernatural abilities. Thanks to the contributions and skepticism of Houdini and three others (there were five in the committee), the prize was never collected. As his fame as a "ghostbuster" grew, Houdini took to attending séances in disguise, accompanied by a reporter and police officer. Possibly the most famous medium whom he debunked was the Boston medium Mina Crandon, also known as "Margery". Houdini chronicled his debunking exploits in his book A Magician Among the Spirits.

These activities cost Houdini the friendship of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes. Doyle, a firm believer in spiritualism during his later years, refused to believe any of Houdini's exposés. Doyle actually came to believe that Houdini was a powerful spiritualist medium, had performed many of his stunts by means of paranormal abilities, and was using these abilities to block those of other mediums that he was 'debunking' (see Doyle's The Edge of The Unknown, published in 1931, after Houdini's death). This disagreement led to the two men becoming public antagonists. Gabriel Brownstein has written fictionalized account of the meetings of Houdini, Doyle, and Margery in The Man from Beyond: A Novel (2005).

The new book The Secret Life of Houdini has an account of Doyle's involvement with the camp of "Margery" and presents personal letters showing it was strongly believed by Doyle and Mina's husband that revenging spirits (not persons) would soon kill Houdini for hiding the "truth". The book further proposes Doyle's campaign to hijack Houdini's legacy when a Spiritualist minister friend of Doyle, Rev. Arthur Ford (a marvelous teller of tales, some stretched taller than reality),[12] conspired with him to bring messages from Houdini and his mother back from the grave in séances, including one on the roof of the Knickerbocker Hotel, that would further the Spiritualist's agenda. According to the book, Houdini's wife felt so depressed that she actually tried to commit suicide on the eve of the séance. There is no mention of the fact that twelve days after the séance Bess Houdini wrote a moving letter to Walter Winchell, the columnist, that was published in the Graphic, denying the words she received from her deceased husband were given to Ford by herself, denying the charge Bess and Ford had conspired together to perform a publicity stunt to further their careers in the entertainment industry. She trusted Ford's reading.[13][14] Neither is there any mention of the fact that the Houdini code was already widely known by the public months before the séance. (See Arthur Ford)

Death

The most widespread account is that Houdini's ruptured appendix was caused by multiple blows to his abdomen from a McGill University student, J. Gordon Whitehead, in Montreal on October 22. The eyewitnesses to this event were two McGill University students named Jacques Price and Sam Smilovitz (sometimes called Jack Price and Sam Smiley). Their accounts generally agreed. The following is according to Price's description of events. Houdini was reclining on his couch after his performance, having an art student sketch him. When Whitehead came in and asked if it was true that Houdini could take any blow to the stomach, Houdini replied in the affirmative. In this instance, he was hit three times, before Houdini protested. Whitehead reportedly continued hitting Houdini several times afterwards, and Houdini acted as though he were in some pain. Price recounted that Houdini stated that if he had had time to prepare himself properly, he would have been in better position to take the blows. After taking statements from Price and Smilovitz, Houdini's insurance company concluded that the death was due to the dressing room incident and paid double indemnity.[15]

When Houdini arrived at the Garrick theater in Detroit, Michigan, on October 24, 1926, for what would be his last performance, he had a fever of 104 degrees F (40°C). Despite a diagnosis of acute appendicitis, Houdini took the stage. Afterwards, he was hospitalized at Detroit's Grace Hospital.[16] Houdini died of peritonitis from a ruptured appendix at 1:26 p.m. on October 31 (Halloween) in room 401, 1926, at the age of 52.

Despite this, modern medical knowledge gives no reason to believe Houdini's acute appendicitis was caused by any physical trauma. McGill University's archive supported this idea:[citation needed]

It appears that Whitehead's punch to Houdini's stomach, while not fatal, aggravated an existing but still undetected case of appendicitis. Although in serious pain, Houdini nonetheless continued to travel without seeking medical attention.

Harry had apparently been suffering from appendicitis for several days and refusing medical treatment. His appendix would likely have burst on its own without the trauma.[17]

Some people have suggested the possibility that Houdini died of poisoning. Houdini attempted to debunk the work of a group of psychics known as the 'Spiritualists', and members of this group, such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, were clearly at odds with him in the later part of his life. There is evidence that suggests that one or more supporters of the Spiritualists murdered Houdini, possibly by poisoning his food with arsenic or another deadly substance. In 2007, some of Houdini's descendants and several notable forensic pathologists tried to gain permission to exhume Houdini's remains and search for evidence of poisoning. Dr. Michael Baden, who chaired panels re-investigating the deaths of President John F. Kennedy and civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., pointed out an oddity in Houdini's death certificate: it noted that his appendix was on the left side, rather than the right.[18]

Houdini's funeral was held on November 4, 1926 in New York, with over two thousand mourners in attendance. He was interred in the Machpelah Cemetery in Queens, New York, with the crest of the Society of American Magicians inscribed on his grave site. The Society holds their "Broken Wand" ceremony at the grave site on the anniversary of his death to this day. Houdini's wife, Bess, died in February, 1943, and was not permitted to be interred with him at Machpelah Cemetery because she was a gentile. Bess Houdini is interred at Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Hawthorne, New York.

In Houdini's will, his vast library was offered to the American Society for Psychical Research on the condition that research officer and editor of the ASPR Journal, J. Malcolm Bird, resign. Bird refused and the collection went instead to the Library of Congress.

Fearing spiritualists would exploit his legacy by pretending to contact him after his death, Houdini left his wife a secret code — ten words chosen at random from a letter written by Doyle — that he would use to contact her from the afterlife.[19] His wife held yearly séances on Halloween for ten years after his death, but Houdini never appeared. In 1936, after a last unsuccessful séance on the roof of the Knickerbocker Hotel, she put out the candle that she had kept burning beside a photograph of Houdini since his death, later (1943) saying "ten years is long enough to wait for any man." The tradition of holding a séance for Houdini continues by magicians throughout the world to this day, and is currently organized by Sidney H. Radner.[4] and others including at the Houdini Museum in Scranton, PA by Dorothy Dietrich.[5]

Appearance and voice

Unlike the image of the classic magician, Houdini was short and stocky and typically appeared on stage in a long frock coat and tie. Most biographers peg his height as 5'5", but descriptions vary. Houdini was also said to be slightly bow-legged, which aided in his ability to gain slack during his rope escapes. In the 1996 biography Houdini!!!: The Career of Ehrich Weiss, author Kenneth Silverman summarizes how reporters described Houdini's appearance during his early career:

They stressed his smallness – "somewhat undersized" – and angular, vivid features: "He is smooth-shaven with a keen, sharp-chinned, sharp-cheekboned face, bright blue eyes and thick, curly, black hair." Some sensed how much his complexly expressive smile was the outlet of his charismatic stage presence. It communicated to audiences at once warm amiability, pleasure in performing, and, more subtly, imperious self-assurance. Several reporters tried to capture the charming effect, describing him as "happy-looking", "pleasant-faced", "good natured at all times", "the young Hungarian magician with the pleasant smile and easy confidence."[20]

The only known recording of Houdini's voice reveals it to be heavily accented. Houdini made these recordings on Edison wax cylinders on October 24, 1914, in Flatbush, New York. On them, Houdini practices several different introductory speeches for his famous Chinese Water Torture Cell. He also invites his sister, Gladys, to recite a poem. Houdini then recites the same poem in German. The six wax cylinders were discovered in the collection of magician John Mulholland after his death in 1970.[21] They are currently part of the David Copperfield collection.

Artifacts

Houdini's brother, Theodore Hardeen, who returned to performing after Houdini's death, inherited his brother's effects and props. Houdini's will stipulated that all the effects should be "burned and destroyed" upon Hardeen's death. But Hardeen sold much of the collection to magician and Houdini enthusiast Sidney H. Radner during the 1940s, including the famous Water Torture Cell. Radner allowed choice pieces of the collection to be displayed at The Houdini Magical Hall of Fame in Niagara Falls, Canada. In 1995, a mysterious fire destroyed the museum and its contents. While the Water Torture Cell was reported to have been destroyed, its metal frame remained, and the cell was restored by illusion builder John Gaughan.[22]

Radner archived the bulk of his collection at the Houdini Museum in Appleton Wisconsin, but pulled it in 2003 and auctioned it off in Las Vegas on October 30, 2004. Many of the choice props, including the restored Water Torture Cell, are now owned by David Copperfield.[23]

Proposed exhumation

On March 22, 2007, around 80 years after Houdini died, his grandnephew George Hardeen announced that the courts would be asked to allow exhumation of Houdini's body. The purpose was to look for evidence that Houdini was poisoned by Spiritualists, as suggested in The Secret Life of Houdini.[24] In a statement given to the Houdini Museum in Scranton, Jeff Blood opposed the application and suggested it was a publicity ploy for the book. Blood is Houdini's grandnephew on his wife's side.[25]

Legacy

- 1936 - On October 31, 1936, Houdini's widow held the "Final Houdini Seance" atop of the roof of The Knickerbocker Hotel in Hollywood California. While Houdini did not come back, a sudden mysterious rain storm after the memorial candle had been extinguished led some press to speculate this was Houdini's way of signaling from beyond the grave. A recording of the seance was made and issued as a record album.

- 1953 - A mostly fictionalized biopic of Houdini's life was made in 1953 starring Tony Curtis, and called simply Houdini. Most of the misconceptions about Houdini's life are due in part to this film. For example, it heavily implies his death was from Houdini's failure to escape the Chinese Water Torture Cell, caused by an appendicitis. (Curtis' Houdini agrees to seek medical attention "when the tour is over".)

- 1968 - The Houdini Magical Hall of Fame was opened on Clifton Hill in Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada. At its opening, this museum contained the majority of Houdini's personal collection of magic paraphernalia. One of Houdini's death wishes was that his entire collection be given to his brother Theodore (also known as the magician Hardeen), and burned upon Theodore's death. Against his wishes, forty years after Houdini's death, the items were taken from storage and sold. Two entrepreneurs purchased the items and renovated a former meat packing plant on Clifton Hill, Ontario, Canada, to house the museum. The museum was moved in 1972 to its final location on the top of Clifton Hill. Séances were held every year at the museum on October 31, the anniversary of Houdini's death. It has been rumored that in 1974, on the seventh séance held at the museum, medium Ann Fisher asked Houdini to make his presence known. Immediately a pot of flowers fell from a shelf along with a book about Houdini; the book opened to a page featuring a Houdini poster entitled Do Spirits Return?.[citation needed] In 1995, a fire destroyed the museum and the majority of its contents.[citation needed]

- 1968 - Stuart Damon plays Houdini in a lavishly staged London musical, Man of Magic.

- 1975 - Houdini received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. The star is located on the north west corner of Hollywood Blvd. and Orange Drive, just across from the Grauman's Chinese Theater and down the street from The Magic Castle.

- 1976 - Houdini was played by Paul Michael Glaser of Starsky and Hutch fame in a 1976 TV movie called The Great Houdinis (aka The Great Houdini) which was also highly fictionalized. The film focused on Houdini's relationship with his wife and mother, whom it portrayed as frequently bickering (although in reality they had cordial relations) and his fascination with life after death. The cast also included Sally Struthers, Bill Bixby, and Ruth Gordon.

- 1978 - Houdini was a key historical figure appearing in Ragtime the 1978 novel, the 1981 film and the 1998 musical.

- 1982 - The Kate Bush album The Dreaming includes a song inspired by Houdini and his wife.

- 1985 - The City of Appleton constructed Houdini Plaza on the site of their home.

- 1985 - Wil Wheaton played Houdini in Young Harry Houdini, a made for TV movie which aired on ABC as a "Disney Sunday Movie." The film also featured Jeffrey DeMunn as the adult Houdini. DeMunn first played Houdini in the film version of, Ragtime.[26]

- 1993 - Grunge rock band The Melvins released Houdini, their second album. In the band illustration, each band member is shown with six fingers (Houdini sometimes used a fake sixth finger to hide lock picks).

- 1996 - Australian Rock Band The Church released their album, Magician Among the Spirits, inspired by Houdini's life, and features a negative of a photograph of Houdini on the cover.

- 1997 - Actor Harvey Keitel plays Houdini and Peter O'Toole Conan Doyle in the film FairyTale: A True Story, set during World War I and portraying the alleged photographing of live fairies by two English schoolgirls. The two are seen as collegial even though they disagree as to the validity of spiritualism.

- 1998 - Ragtime, the Broadway musical version of the movie, premiered on January 18, 1998. It featured Houdini as a character and has a song called "Harry Houdini, Master Escapist". The book was written by Terrence McNally, with music and lyrics by Stephen Flaherty and Lynn Ahrens. The play ran on Broadway until January 16, 2000, and won 4 Tony Awards.

- 1998 - Johnathon Schaech played Houdini in the TNT original movie Houdini. The film co-starred Stacy Edwards as Bess and Mark Ruffalo as his brother, Dash (aka Theo. Hardeen). The TV movie first aired on December 6, 1998.

- 1999 - Novelist Norman Mailer played Houdini in the highly experimental film Cremaster 2, which told the story of murderer Gary Gilmore who in real life claimed to be related to Houdini.[26]

- 2002 - The United States Postal Service issued a postage stamp with a replica of Houdini's favorite publicity poster on July 3, 2002.[27]

- 2007 - Houdini - The Musical, a theatrical production based on the life of Houdini premiered at the The Playhouse, Weston-super-Mare before going on tour across the United Kingdom.[28] The show features many of Houdini's famous acts including the Chinese Water Torture Cell.

- 2007 - A new film, Death Defying Acts, starring Guy Pearce and Catherine Zeta-Jones, will be release by The Weinstein Company in 2007. Described as a “supernatural romantic thriller”, the film tells the fictional story of Houdini’s relationship with a Scottish psychic in 1926.

- Penn and Teller make references to Houdini in their show Bullshit!. They are doing some of the same things that Houdini did, magic tricks, and debunking the supernatural.

- There is a Houdini Museum in Scranton, Pennsylvania. It claims to be the only building in the world entirely dedicated to Houdini and is run by magicians Dick Brooks and Dorothy Dietrich. The museum also holds an annual Houdini Séance.

- While touring in the United States, Houdini met Joe Keaton and his family vaudeville act. It's said that after Joe's young son fell down a flight of stairs unscathed, Houdini remarked "Your kid is quite the buster" (buster being a stage name for a fall) and gave a name to comedy legend Buster Keaton (the kid).

Publications

Houdini published numerous books during his career (some of which were written by his good friend Walter Brown Gibson, the creator of The Shadow [6]):

- The Right Way to Do Wrong (1906)

- Handcuff Secrets (1907)

- The Unmasking of Robert Houdin (1908)

- Magical Rope Ties and Escapes (1920)

- Miracle Mongers and their Methods (1920)

- Houdini's Paper Magic (1921)

- A Magician Among the Spirits (1924)

- Under the Pyramids (1924) with H.P. Lovecraft.

Biographies

- Houdini: His Life-Story by Harold Kellock, from the recollections and documents of Beatrice Houdini, Harcourt, Brace Co., June, 1928

- The Great Houdini: Magician Extraordinary by Beryl Williams & Samuel Epstein, Julian Messner, Inc., NY, 1950

- Houdini: The Man Who Walked Through Walls by William Lindsay Gresham, Henry Holt & Co, NY, 1959

- Houdini: Master of Escape by Lance Kendall, Macrae Smith & Co., NY, 1960

- Houdini: The Untold Story by Milbourne Christopher, Thomas Y. Crowell Co, 1969

- Houdini: A Mind in Chains by Bernard C. Meyer, M.D., E.P. Dutton & Co. NY, 1976

- Houdini: His Life and Art by James Randi & Bert Randolph Sugar, Grosset & Dunlap, NY, 1977

- Houdini: His Legend and His Magic by Doug Henning with Charles Reynolds, Times Books, NY, 1978

- The Life and Many Deaths of Harry Houdini by Ruth Brandon, Seeker & Warburg, Ltd. GB, 1993

- Houdini!!!: The Career of Ehrich Weiss by Kenneth Silverman, 1996 ISBN 006092862X

- The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America's First Superhero by William Kalush and Larry Sloman, 2006 ISBN 0743272072

Further reading

- Houdini's Escapes and Magic by Walter B. Gibson, Prepared from Houdini’s private notebooks Blue Ribbon Books, Inc., 1930. Reveals some of Houdini's magic and escape methods (also released in two separate volumes: Houdini's Magic and Houdini's Escapes).

- The Secrets of Houdini by J.C. Cannell, Hutchinson & Co., London, 1931. Reveals some of Houdini's escape methods.

- Houdini and Conan Doyle: The Story of a Strange Friendship by Bernard M. L. Ernst, Albert & Charles Boni, Inc., NY, 1932.

- Sixty Years of Psychical Research by Joseph F. Rinn, Truth Seeker Co., 1950, Rinn was a long time close friend of Houdini. Contains detailed information about the last Houdini message (there are 3) and its disclosure.

- Houdini's Fabulous Magic by Walter B. Gibson and Morris N. Young Chilton, NY, 1960. Excellent reference for Houdini’s escapes and some methods (includes the Water Torture Cell).

- The Houdini Birth Research Committee’s Report, Magico Magazine (reprint of report by The Society of American Magicians), 1972. Concludes Houdini was born March 24, 1874 in Budapest.

- Mediums, Mystics and the Occult by Milbourne Christopher, Thomas T. Crowell Co., 1975, pp 122-145, Arthur Ford-Messages from the Dead, contains detailed information about the Houdini messages and their disclosure.

- Arthur Ford: The Man Who Talked with the Dead by Allen Spraggett with William V. Rauscher, 1973, pp 152-165, Chapter 7, The Houdini Affair contains detailed information about the Houdini messages and their disclosure.

- Houdini: Escape into Legend, The Early Years: 1862-1900 by Manny Weltman, Finders/Seekers Enterprises, Los Angeles, 1993. Examination of Houdini’s childhood and early career.

- Houdini Comes To America by Ronald J. Hilgert, The Houdini Historical Center, 1996. Documents the Weiss family’s immigration to the United States on July 3, 1878 (when Ehrich was 4).

- Houdini Unlocked by Patrick Culliton, Two volume box set: The Tao of Houdini and The Secret Confessions of Houdini, Kieran Press, 1997.

- The Houdini Code Mystery: A Spirit Secret Solved by William V. Rauscher, Magic Words, 2000.

- The Man Who Killed Houdini by Don Bell, Vehicule Press, 2004. Investigates J. Gordon Whitehead and the events surrounding Houdini's death.

See also

- Arthur Ford

- James Randi

- Dorothy Dietrich

- Joseph Dunninger

- Dai Vernon

- Wonder of the Worlds

- David Copperfield

External links

- Houdini Tribute 400+ Photos, videos, multimedia, and hear Houdini's voice

- Timeline of Houdini's life

- Biographical resources dedicated to Harry Houdini

- The Houdini Museum in Scranton Pennsylvania

- House of Deception article on Houdini's handwriting & signature

- Harry Houdini's Gravesite

- CFI's 10th Annual Houdini Séance - Halloween 2006 - seance held to get in touch with Houdini, Point of Inquiry, 31 October, 2006.

- Houdini Lives! - What's new in the world of Houdini

- CNN report on possible murder of Houdini

- Houdini Historical Center, Appleton, WI

- Houdini in Russia

References

- ^ US National Archives Microfilm serial: M237; Microfilm roll: 413; Line: 38; List number: 684

- ^ Saml M. Weiss, Cecelia (wife), Armin M., Nathan J., Ehrich, Theodore, and Leopold. 1880 US Census

- ^ Houdini!!!: The Career of Ehrich Weiss by Kenneth Silverman, 1996, page 81

- ^ Houdini!!!: The Career of Ehrich Weiss by Kenneth Silverman, 1996, page 109

- ^ The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America's First Superhero by William Kalush and Larry Sloman, 2006

- ^ Houdini!!!: The Career of Ehrich Weiss by Kenneth Silverman, 1996, pages 59-62

- ^ Houdini!!!: The Career of Ehrich Weiss by Kenneth Silverman, 1997, pages162-165

- ^ Houdini!!!: The Career of Ehrich Weiss by Kenneth Silverman, 1996, pages 137-154

- ^ Houdini!!!: The Career of Ehrich Weiss by Kenneth Silverman, 1996, pages 205

- ^ Houdini!!!: The Career of Ehrich Weiss by Kenneth Silverman, 1996, pages 226-249

- ^ "Haldane wows at LA screening".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Arthur Ford: The Man Who Talked with the Dead, by Allen Spraggett with William V. Rauscher, New American Library, 1974

- ^ Mediums, Mystics and the Occult by Milbourne Christopher, Thomas T. Crowell Co., 1975, pp. 132 & 133

- ^ Houdini: The Untold Story, Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1969, page 258

- ^ The Man Who Killed Houdini by Don Bell, Vehicule Press, 2004.

- ^ http://www.snopes.com/horrors/freakish/houdini.asp

- ^ Benoit, Tod (2003). Where Are They Buried? How Did They Die?. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. p. 469. ISBN 1-57912-287-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Guardian article on suspicions of poisoning and the exhumation

- ^ Colin Groves in Skeptical - a Handbook of Pseudoscience and the Paranormal, ed Donald Laycock, David Vernon, Colin Groves, Simon Brown, Imagecraft, Canberra, 1989, ISBN 0731657942, p16

- ^ Houdini!!!: The Career of Ehrich Weiss by Kenneth Silverman, 1996, pages 31

- ^ Houdini Up To Old Tricks Through Magic of Edison, Los Angeles Times, July 4, 1970

- ^ "The Mystery of the Two Torture Cells". Houdini Lives!. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Grandnephew seeks to 'set record straight' about Houdini's death".

{{cite web}}: Text "Canadian Broadcasting Corporation" ignored (help) - ^ "Family Statement re: exhumation".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b The Great Escape: Hollywood's Struggle to Bring Houdini Back to Life by John Cox, MAGIC Magazine, October 2006

- ^ USPS Press Release (October 31, 2001) Harry Houdini Returns To World Stage, usps.com

- ^ "Houdini - The Musical". Smile Productions Ltd. Retrieved 2007-06-06.