Battle of Waterloo

| Battle of Waterloo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Napoleonic Wars (Seventh Coalition 1815) | |||||||

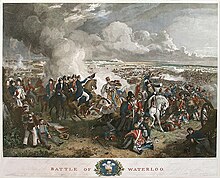

The Battle of Waterloo by William Sadler | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Seventh Coalition: File:Flag of Nassau-Weilburg.png Duchy of Nassau | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 73,000 |

67,000 Coalition 60,000 Prussian (48,000 engaged by about 18:00) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

25,000 dead or wounded, 7,000 Captured, 15,000 Missing [1] | 22,000 dead or wounded[2] | ||||||

50°40′45″N 4°24′25″E / 50.67917°N 4.40694°E

The Battle of Waterloo, fought on 18 June 1815, was Napoleon Bonaparte's last battle. His defeat put a final end to his rule as Emperor of the French. Waterloo also marked the end of the period known as the Hundred Days, which began in March 1815 after Napoleon's return from Elba, where he had been exiled after his defeats at the Battle of Leipzig in 1813 and the campaigns of 1814 in France.

After Napoleon returned to power, many states which had previously resisted his rule formed the Seventh Coalition and began to assemble armies to oppose him. The first two armies to assemble close to the French frontier were a Prussian army under the command of Gebhard von Blücher and an allied army under the command of the Duke of Wellington. These armies were close to France's north-east frontier, and Napoleon chose to attack them in the hope of destroying them before they, with other members of the Seventh Coalition (who were not such an immediate threat), could join in a coordinated invasion of France. The campaign consisted of four major battles, that of Waterloo proving decisive.

The nearest run thing you ever saw in your life.

— Wellington, [3]

Napoleon chose to delay the start of the Battle of Waterloo until late in the morning of 18 June to give the ground time to dry out a little from the rain that had fallen during the night. The allied army positioned across the Brussels road on the Mont St. Jean escarpment withstood repeated attacks by the French until in the evening they counter-attacked and drove the French from the field. Simultaneously the Prussians — arriving in force — broke through Napoleon's right flank adding their weight to the attack.

The French army left the battlefield in disorder and was unable to prevent Coalition forces entering France and the restoration of King Louis XVIII to the French throne. Napoleon was exiled to the British island of St. Helena where he remained until his death in 1821. Although the Coalition forces won the battle, losses were great on both sides.

The battlefield is in present-day Belgium, about 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) SSE of Brussels, and 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from the town of Waterloo.

Prelude

As far back as 13 March 1815, six days before Napoleon reached Paris, the powers at the Congress of Vienna declared him an outlaw.[4] Four days later, the United Kingdom, Russia, Austria, and Prussia mobilized armies to defeat Napoleon.[5] Napoleon knew that, once his attempts at dissuading one or more of the Seventh Coalition Allies from invading France had failed, his only chance of remaining in power was to attack before the Coalition put together an overwhelming force. If he could destroy the existing Coalition forces south of Brussels before they were reinforced, he might be able to drive the British back to the sea and knock the Prussians out of the war.

Wellington expected Napoleon to try to envelope the Coalition armies (a manoeuvre that he had successfully used many times before) by moving through Mons to the south-west of Brussels.[6] The roads to Mons were paved, which would have enabled a rapid flank march. This would have cut Wellington's communications with his base at Ostend, but would also have pushed his army closer to Blücher's. In fact, Napoleon planned instead to divide the two Coalition armies and defeat them separately, and he encouraged Wellington's misapprehension with false intelligence.[7] Moving up to the frontier without alerting the Coalition, Napoleon divided his army into a left wing, commanded by Marshal Ney, a right wing commanded by Marshal Grouchy, and a reserve, which he commanded personally (although all three elements remained close enough to support one another). Crossing the frontier at Thuin near Charleroi before dawn on 15 June, the French rapidly over-ran Coalition outposts and secured Napoleon's favoured "central position" — at the juncture between the area where Wellington's allied army was cantoned to his north-west, and Blücher's Prussian army that was dispersed to the north-east in the vicinity of Sombreffe.

Only very late on the night of 15 June was Wellington certain that the Charleroi attack was the main French thrust, and he duly ordered his army to deploy near Nivelles and Quatre Bras. Early on the morning of 16 June at the Duchess of Richmond's ball, on receiving a dispatch from the Prince of Orange, he was shocked by the speed of Napoleon's advance. Hastily, he sent his army in the direction of Quatre Bras, where the Prince of Orange, with the brigade of Prince Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar, was holding a tenuous position against the French left, commanded by Marshal Ney.[8] Ney's orders were to secure the crossroads of Quatre Bras, so that if necessary, he could later swing east and reinforce Napoleon.

As Napoleon considered the concentrated Prussian army the greater threat, he moved against them first. Lieutenant-General Graf von Zieten's I Corps rearguard action on 15 June held up the French advance, giving Blücher the opportunity to concentrate his forces in the Sombreffe position, which had been selected earlier for its good defensive attributes. On 16 June, Napoleon, with the reserve and the right wing of the army, attacked and defeated Blücher's Prussians at the Battle of Ligny. The Prussian centre gave way under heavy French attack, but the flanks held their ground.

Ney, meanwhile, advancing against Quatre Bras on the same day, found it lightly held by the Prince of Orange. The latter successfully repelled Ney's initial attacks, but were gradually driven back by overwhelming numbers of French troops. As the Battle of Quatre Bras developed, the allies were steadily reinforced. Wellington arrived in the middle of the afternoon and took command of the Anglo-allied forces engaged in the battle. By late afternoon, Wellington was able to counter-attack and drive the French back from the crossroads. The Prussian defeat at Ligny on the same day made the Quatre Bras position untenable. Wellington spent 17 June falling back northwards, to a defensive position he had personally reconnoitred the previous year at Mont St Jean, a low ridge south of the village of Waterloo and the Forest of Soignes.[9]

The retreat of the Prussians from Ligny was uninterrupted, and seemingly unnoticed, by the French.[10] By nightfall, at about 21:00, almost all of the Prussian formations had left the field. Crucially, they retreated not to the east, along their own lines of communication and away from Wellington, but northwards, parallel to Wellington's line of march and still within supporting distance, and remained throughout in communication with Wellington. On the Prussian right, Graf von Zieten's I Corps retreated slowly with most of its artillery, leaving a rearguard close to Brye to slow any French pursuit. On the left, Lieutenant-General Thielemann's III Corps retreated unmolested, leaving a strong rearguard at Sombreffe. The bulk of the rearguard units held their positions until about midnight, before following the rest of the retreating army. In fact, Graf von Zieten's I Corps rearguard only left the battlefield in the early morning of 17 June, as the exhausted French had failed to press on.[11] Pirch I's II Corps followed I Corps off the battlefield and Thieleman's III Corps moved last with the army's various supply parks in tow. It should be noted that the last of III Corps moved out in the morning and was completely ignored by the French.[11] Von Bülow's IV Corps, which had not been engaged at Ligny, moved south of Wavre and set up a strong position on which the other elements of the Prussian army could reassemble.[11]

Napoleon, with the reserves, made a late start on 17 June and joined Ney at Quatre Bras at 13:00 to attack Wellington's army, but found the position empty. The French pursued Wellington, but the result was only a brief cavalry skirmish in Genappe just as torrential rain set in for the night. Before leaving Ligny, Napoleon ordered Grouchy, commander of the right wing of the Army of the North (about 33,000 men), to follow up the retreating Prussians. A late start, uncertainty about the direction the Prussians had taken, and the vagueness of the orders given to him meant that Grouchy was too late to prevent the Prussian army reaching Wavre, from where it could march to support Wellington. By the end of 17 June, Wellington's army had arrived at its position at Waterloo, with the main body of Napoleon's army following. Blücher's army was gathering in and around Wavre, around eight miles (13 km) to the east.

Armies

Three armies were involved in the battle: Napoleon's Armée du Nord, a multinational army under Wellington, and a Prussian army under Blücher. The French army of around 69,000 consisted of 48,000 infantry, 14,000 cavalry, and 7,000 artillery with 250 guns.[12] Napoleon had used conscription to fill the ranks of the French army throughout his rule, but he did not conscript men for the 1815 campaign. All his troops were veterans of at least one campaign who had returned more or less voluntarily to the colours. The cavalry in particular was both numerous and formidable, and included fourteen regiments of armoured heavy cavalry and seven of highly versatile lancers. Neither allied army had any armoured troops at all, and Wellington had only a handful of lancers.

Wellington said he had "an infamous army, very weak and ill-equipped, and a very inexperienced Staff".[13] His Anglo-allied force consisted of 67,000 men; 50,000 infantry, 11,000 cavalry, and 6,000 artillery with 150 guns. Of these, 24,000 were British, with another 6,000 from the King's German Legion All these were regular troops, 7,000 of whom were Peninsular War veterans.[14] In addition, there were 17,000 troops from the Netherlands, 11,000 from Hanover, 6,000 from Brunswick, and 3,000 from Nassau.[15] These allied armies had been re-established in 1815, following the earlier defeat of Napoleon. Most of the professional soldiers in these armies had spent their careers in the armies of France or Napoleonic regimes, with the exception of some from Hanover and Brunswick who had fought with the British army in Spain. The main variation in the quality of troops was between regular troops and the militia troops in the continental armies, who were sometimes very young and inexperienced.[16][17] Wellington was also acutely short of heavy cavalry, having only seven British and three Dutch-Belgian regiments. The Duke of York imposed many of Wellington's staff officers on him, including his second-in-command, the Earl of Uxbridge. Uxbridge commanded the cavalry which and had carte blanche from Wellington. A further 17,000 Anglo-allied troops were stationed at Hal, eight miles (11.2 km) away to the west, and were not recalled to participate in the battle.

The Prussian army was in the throes of reorganization. Prussian infantry regiments consisted of one fusilier battalion and two musketeer battalions, plus a company of grenadiers. Fusiliers were trained to fight as light infantry; the regiments' grenadier companies were usually detached into ad hoc battalions. Many regiments also had attached companies of Schützen - volunteer light infantry, often equipped with rifles. A Prussian regiment at full establishment numbered around 2,500 effectives, and thus approached the strength of a French or British brigade, while a Prussian brigade - three such regiments - was of a size similar to other armies' divisions. In 1815, Prussia's former Reserve regiments, Legions, and Freikorps volunteer formations from the wars of 1813 - 14 were in the process of being absorbed into the line, along with many Landwehr (militia) regiments. Although Prussia's militia units were in the main significantly better than other militias,[18] the Landwehr formations with Blücher's army of 1815 were mostly untrained and inequipped when they arrived in Belgium, both of which deficiencies had to be addressed during the two months that the Prussian army spent in Belgium prior to the battle. The Prussian cavalry were in a similar state. [19] Its artillery was also reorganizing and would not give its best performance - guns and equipment would continue to arrive during and after the battle. This army was called on to fight at Waterloo just two days after defeat at Ligny, a battle that had cost the army some 14,500 dead and wounded. Offsetting these handicaps, however, the Prussian Army did have excellent and professional leadership in its General Staff organization. The genesis of what would become the General Staff system of the German Army, this was a thoroughly professional organization working to a single system. It allowed the Prussian army to accomplish feats that would have been considered very difficult at this time. This staff system ensured that for Ligny, three-quarters of the Prussian army assembled and were ready for battle at 24 hours' notice. After Ligny, the Prussian army, although defeated, was able to realign its supply train, reorganize itself, and intervene decisively on the Waterloo battlefield within 48 hours. [20] Nominally under the command of Blücher, much of the Prussian army's operations were in fact directed by his chief-of-staff, Gneisenau, who greatly distrusted Wellington.[21] Two and a half Prussian army corps, or 48,000 men, were engaged at Waterloo by about 18:00. (Two brigades under Friedrich von Bülow, commander of IV Corps, attacked Lobau at 16:30, Georg von Pirch's while II Corps and parts of Graf von Ziethen's I Corps engaged at about 18:00.)

Battlefield

The Waterloo position was a strong one. It consisted of a long ridge running east-west, perpendicular to and bisected by the main road to Brussels. Along the crest of the ridge ran the Ohain road, a deep sunken lane. Near the crossroads with the Brussels road was a large elm tree that was roughly in the centre of Wellington's position and served as his command post for much of the day. Wellington deployed his infantry in a line just behind the crest of the ridge following the Ohain road. Using the reverse slope, as he had many times previously, nowhere could Wellington's strength actually be seen by the French except for his skirmishers and artillery.[22] The length of front of the battlefield was also relatively short at two and a half miles (4 km), allowing Wellington to draw up his forces in depth, which he did in the centre and on the right, all the way towards the village of Braine-l'Alleud, with the expectation that the Prussians would reinforce his left during the day.[23]

In front of the ridge, there were three positions that could be fortified. On the extreme right was the chateau, garden, and orchard of Hougoumont. This was a large and well-built country house, initially hidden in trees. The house faced north along a sunken, covered lane (or hollow way) along which it could be supplied. On the extreme left was the hamlet of Papelotte. Both Hougoumont and Papelotte were fortified and garrisoned, and thus anchored Wellington's flanks securely. Papelotte also commanded the road to Wavre that the Prussians would use to send reinforcements to Wellington's position. On the western side of the main road, and in front of the rest of Wellington's line, was the farmhouse and orchard of La Haye Sainte, which was garrisoned with 400 light infantry of the King's German Legion.[24] On the opposite side of the road was a disused sand quarry, where the 95th Rifles were posted as sharpshooters. This position presented a formidable challenge to an attacker. Any attempt to turn Wellington's right would entail taking the entrenched Hougoumont position; any attack on his right centre would mean the attackers would have to march between enfilading fire from Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte. On the left, any attack would also be enfiladed by fire from La Haye Sainte and its adjoining sandpit, and any attempt at turning the left flank would entail fighting through the streets and hedgerows of Papelotte, and some very wet ground.[25]

The French army formed on the slopes of another ridge to the south where there was an inn called La Belle Alliance. Napoleon desired flexibility but could not see Wellington's positions, so he drew his forces up symmetrically about the Brussels road. On the right was I Corps under d'Erlon with 16,000 infantry and 1,500 cavalry and a cavalry reserve of 4,700; on the left II Corps under Reille with 13,000 infantry, and 1,300 cavalry, and a cavalry reserve of 4,600; and in the centre about the road south of La Belle Alliance a reserve including Lobau's VI Corps with 6,000 men, the 13,000 infantry of the Imperial Guard, and a cavalry reserve of 2,000.[26] On the right of the rear of the French position was the substantial village of Plancenoit, and at the extreme right, the wood Bois de Paris. Napoleon initially commanded the battle from south of La Belle Alliance at Rossomme farm where he could see the entire battlefield, but moved to the inn early in the afternoon. Command on the battlefield (which was largely hidden from him) was delegated to Ney.[27]

Battle

Wellington was up very early, around 02:00 or 03:00 on the morning of 18 June, and wrote letters until dawn. He had written to Blücher confirming with him that he would give battle at Mont St Jean provided Blücher would provide him with at least a corps, otherwise he would retreat towards Brussels. At a late night council, Blücher managed to persuade Gneisenau to join Wellington's army and in the morning Wellington received dispatches promising him three corps.[28] After 06:00 Wellington was out supervising the deployment of his forces. The Prussian IV Corps under Bülow was designated to lead the march to Waterloo as it was in the best shape having not been involved in the Battle of Ligny. Although they had not taken casualties, IV Corps had been marching for two days covering the retreat of the other three corps of the Prussian army from the battlefield of Ligny. They had been posted farthest away from the battlefield and progress was very slow. The roads were in poor condition after the night's heavy rain, and Bülow's men had to pass through the congested streets of Wavre, along with 88 pieces of corps artillery. Matters were not helped by a fire which broke out in Wavre and blocked several streets along Bülow's intended route. As a result, the last part of the corps left at 10:00, six hours after the leading elements had moved out towards Waterloo. Bülow's men would be followed to Waterloo first by I Corps and then by II Corps.[29]

Napoleon breakfasted off silver at the house where he had spent the night, Le Caillou. Afterwards, when Soult suggested that Grouchy should be recalled to join the main force, Napoleon said "Just because you have all been beaten by Wellington, you think he's a good general. I tell you Wellington is a bad general, the English are bad troops, and this affair is nothing more than eating breakfast".[30] Later, on being told by his brother, Jerome, of some gossip between British officers overheard at lunch by a waiter at the King of Spain inn in Genappe that the Prussians were to march over from Wavre, Napoleon declared that the Prussians would need at least two days to recover and would be dealt with by Grouchy.[31]

Napoleon had delayed the start of the battle owing to the sodden ground that would have made the manoeuvring of cavalry and artillery very difficult. In addition, many of his forces had bivouacked well to the south of La Belle Alliance. At 10:00, he sent a dispatch to Grouchy in answer to one he had received six hours earlier, telling him to "head for Wavre [to Grouchy's north] in order to draw near to us [to the west of Grouchy]" and then "push before him" the Prussians to arrive at Waterloo "as soon as possible".[32]

At 11:00, Napoleon drafted his general order. He made Mont St Jean the objective of the attack and massed the reserve artillery of I, II, and VI Corps to bombard the centre of Wellington's army's position from about 13:00. A diversionary attack would be made on Hougoumont by Jerome's Corps, which Napoleon expected would draw in Wellington's reserves since its loss would threaten his communications with the sea. D'Erlon's corps then would attack Wellington's left, break through, and roll up his line from east to west. In his memoirs, Napoleon wrote that his intention was to separate Wellington's army from the Prussians and drive it back towards the sea.[33]

Hougoumont

Wellington recorded in his dispatches that "at about ten o'clock [Napoleon] commenced a furious attack upon our post at Hougoumont".[34] Other sources state that this attack was at about 11:30.[35] The historian Andrew Roberts notes that "It is a curious fact about the Battle of Waterloo that no one is absolutely certain when it actually began".[36] The house and its immediate environs were defended by four light companies of Guards and the wood and park by Hanoverian Jäger and the 1/2nd[37] Nassau.[38] The initial attack was by Bauduin's brigade, which emptied the wood and park, but was driven back by heavy British artillery fire and cost Bauduin his life. The British guns were distracted into an artillery duel with French guns and this allowed a second attack by Soye's brigade and then by what had been Bauduin's. This succeeded in reaching the north gate of the house and some French troops managed to get into its courtyard before the gate was secured again. This attack was then repulsed by the arrival of the 2nd Coldstream Guards and 2/3rd Foot Guards.

Fighting continued around Hougoumont all afternoon with its surroundings heavily invested with French light infantry and coordinated cavalry attacks sent against the troops behind Hougoumont. Wellington's army defended the house and the hollow way running north from it. In the afternoon, Napoleon personally ordered the shelling of the house to cause it to burn.[40] resulting in the destruction of all but the chapel. Du Plat's brigade of the King's German Legion was brought forward to defend the hollow way, which they had to do without any senior officers, and were then relieved by the 71st Foot, a Scottish infantry regiment. Adam's brigade, further reinforced by Hew Halkett's 3rd Hanoverian Brigade, successfully repulsed further infantry and cavalry attacks sent by Reille and maintained the occupation of Hougoumont until the end of the battle.

I had occupied that post with a detachment from General Byng's brigade of Guards, which was in position in its rear; and it was some time under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel MacDonald, and afterwards of Colonel Home; and I am happy to add that it was maintained, throughout the day, with the utmost gallantry by these brave troops, notwithstanding the repeated efforts of large bodies of the enemy to obtain possession of it.

— Wellington, [41]

When I reached Lloyd's abandoned guns, I stood near them for about a minute to contemplate the scene: it was grand beyond description. Hougoumont and its wood sent up a broad flame through the dark masses of smoke that overhung the field; beneath this cloud the French were indistinctly visible. Here a waving mass of long red feathers could be seen; there, gleams as from a sheet of steel showed that the cuirassiers were moving; 400 cannon were belching forth fire and death on every side; the roaring and shouting were indistinguishably commixed—together they gave me an idea of a labouring volcano. Bodies of infantry and cavalry were pouring down on us, and it was time to leave contemplation, so I moved towards our columns, which were standing up in square.

— Major Macready, Light Division, 30th British Regiment, Halkett's brigade, [42]

The Hougoumont battle has often been characterised as a diversionary attack to cause Wellington to move reserves to his threatened right flank to protect his communications, which then escalated into an all-day battle that drew in more and more French troops but just a handful of Wellington's, having the exact opposite effect to that intended.[43] In fact there is a good case that both Napoleon and Wellington thought Hougoumont was a vital part of the battle. Hougoumont was a part of the battlefield that Napoleon could see clearly[44] and he continued to direct resources towards it and its surroundings all afternoon (33 battalions in all, 14,000 troops). Similarly, though the house never contained a large number of troops, Wellington devoted 21 battalions (12,000 troops) over the course of the afternoon to keeping the hollow way open to allow fresh troops and ammunition to be admitted to the house. He also moved several artillery batteries from his hard-pressed centre to support Hougoumont.[45]

First French infantry attack

Napoleon had 80 of his guns drawn up to form a grande batterie in the centre. These opened fire at 11:50, according to Lord Hill (commander of the allied II Corps),[46] while other sources put the time between noon and 13:30.[47] The battery was too far back to aim accurately, and the only other troops they could see were part of the Dutch division (the others were employing Wellington's characteristic "reverse slope defence".[48] In addition, the soft ground prevented the cannon balls from bouncing far, and the French gunners covered Wellington's entire deployment, so the density of hits was low. However, the idea was not to cause a large amount of physical damage, but in the words of Napoleon's orders, "to astonish the enemy and shake his morale".[48]

At about 13:00, Napoleon saw the first columns of Prussians around the village of Chapelle St. Lambert, four or five miles (three hours' march for an army) away from his right flank.[49] Napoleon's reaction was to send a message to Grouchy telling him to come towards the battlefield and attack the arriving Prussians.[50] However, Grouchy had been following Napoleon's previous orders to follow the Prussians "with your sword against his back" towards Wavre, and was by now too far away to get to the field at Waterloo. Grouchy was advised by his subordinate, Gérard, to "march to the sound of the guns", but stuck to his orders and engaged the Prussian III Corps rear guard under the command of Lieutenant-General Baron Johann von Thielmann at the Battle of Wavre.

A little after 13:00, the infantry attack of d'Erlon's I Corps began. D'Erlon, like Ney, had encountered Wellington in Spain, and was aware of the British commander's favoured tactic of using massed short-range musketry to drive off infantry columns. Rather than use the usual nine-deep French columns deployed abreast of one another, therefore, each division advanced in closely-spaced battalion lines behind one another. This allowed them to concentrate their fire,[51] but it did not leave room for them to change formation.

The formation was initially effective. Its leftmost division, under Donzelot, advanced on La Haye Sainte. While one battalion engaged the defenders from the front, the following battalions fanned out to either side and, with the support of two brigades of cuirassiers, succeeded in isolating the farmhouse. The Prince of Orange saw that La Haye Sainte had been cut off, and tried to reinforce it by sending forward the Hanoverian Lüneberg Battalion in line. Cuirassiers concealed in a fold in the ground caught and destroyed it in minutes, and then rode on past La Haye Sainte almost to the crest of the ridge, where they covered d'Erlon's left flank as his attack developed.

At about 13:30, d'Erlon started to advance his three other divisions, some 14,000 men over a front of about 1,000 metres (1,094 yd) against Wellington's weak left wing.[52] They faced 6,000 men: the first line consisted of the Dutch 2nd division, the second of British and Hanoverian troops under Sir Thomas Picton, who were lying down in dead ground behind the ridge. Both lines had suffered badly at Quatre Bras; in addition, the Dutch brigade under Bijlandt, posted towards the centre of the battlefield, had deployed on the forward slope and had been exposed to the artillery battery.[53]

As the French advanced, Bijlandt's brigade withdrew to the sunken lane, and then, with nearly all their officers dead or wounded, left the battlefield, leaving just their Belgian battalion, the 7th.[54][55] D'Erlon's men began to ascend the slope, and as they did so, Picton's men stood up and opened fire. The French infantry returned fire and successfully pressured Wellington's troops; although the attack faltered at the centre of Wellington's position,[56] the left wing started to crumble. Picton was killed and the British and Hanoverian troops began to give way under the pressure of numbers.

Charge of the British heavy cavalry

Our officers of cavalry have acquired a trick of galloping at everything. They never consider the situation, never think of manoeuvring before an enemy, and never keep back or provide a reserve.

— Wellington, [57]

At this crucial juncture, the two brigades of British heavy cavalry, formed unseen behind the ridge, were ordered by Uxbridge to charge in support of the hard-pressed infantry. Over twenty years of warfare had eroded the numbers of suitable cavalry mounts available on the European continent; this resulted in the British cavalry entering the 1815 campaign with the finest horses of any contemporary cavalry arm. The British cavalry had also received excellent mounted swordsmanship training. They were, however, considered inferior to the French in manoeuvring in large formations, were cavalier in attitude and, unlike the infantry, had scant experience of warfare. Also, according to Wellington, they had little tactical ability or nous (common sense).[57] The 1st Brigade, known as the Household Brigade, commanded by Major-General Edward Somerset (Lord Somerset), consisted of 'guards regiments': the 1st and 2nd Life Guards, the Royal Horse Guards (the Blues), and the 1st 'King's' Dragoon Guards. The 2nd Brigade, also known as the Union Brigade, commanded by Major-General Sir William Ponsonby, was so-called as it consisted of an English (1st, 'The Royals'), a Scottish (2nd, 'Scots Greys'), and an Irish (6th, 'Inniskilling') regiment of heavy dragoons. The two brigades had a likely combined field strength of about 2,000, and they charged with the forty-seven-year-old Uxbridge leading them and little reserve.[58][59][60]

The Household Brigade charged down the hill in the centre of the battlefield. The French brigade of cuirassiers guarding d'Erlon's left flank were still dispersed and so were swept over the deeply sunken main road and then routed.[61] The sunken lane did not prove a hazard to the cuirassiers because they fell down its sides; rather, it acted as a trap which funnelled their flight to their own right, away from the British cavalry. Some of the cuirassiers found themselves hemmed in by the steep sides of the sunken lane, a confused mass of their own infantry in front of them, the 95th Rifles firing at them from the north side of the lane and Somerset's cavalry still pressing them from behind.[62] The novelty of fighting armoured foes impressed the British cavalrymen, as was recorded by the commander of the Household Brigade.

The blows of the sabres on the cuirasses sounded like braziers at work.

— Lord Somerset, [63]

Continuing their attack, the squadrons on the left of the Household Brigade then destroyed Aulard's Brigade; however, despite attempts to then recall them, they continued past La Haye Sainte and found themselves at the bottom of the hill on blown horses facing Schmitz's brigade formed in squares.

On Wellington's left wing, the Union Brigade suddenly swept through the infantry lines (giving rise to the legend that some of the 92nd Gordon Highland Regiment clung onto their stirrups and accompanied them into the charge).[64] From the centre leftwards, the Royal Dragoons destroyed Bourgeois' brigade, capturing the eagle of the 105th Ligne. The Inniskillings routed the other brigade of Quoit's division, and the Greys destroyed most of Nogue's brigade, capturing the eagle of the 45th Ligne.[65] On Wellington's extreme left, Durutte's division had not yet committed themselves fully to the French advance, and so had time to form squares and fend off groups of Greys.

As with the Household Cavalry, the officers of the Royals and Inniskillings found it very difficult to rein back their troops, who lost all cohesion. James Hamilton, commander of the Greys (that were supposed to form a reserve) ordered a continuation of the charge to the French Grande Batterie and though the Greys had neither the time nor means to disable the cannon or carry them off, they put very many out of action as the gun crews fled the battlefield.[66]

Napoleon promptly responded by ordering a counter-attack from his cavalry reserves by the cuirassier brigades of Farine and Travers. In addition, the two lancer regiments in the I Corps light cavalry division under Jaquinot also counter-attacked. The result was very heavy losses for the British cavalry.[67] All figures quoted for the losses of the cavalry brigades as a result of this charge are estimates, as casualties were only noted down after the day of the battle and were for the battle as a whole.[68][69] A view held by some historians is that the official rolls tend overestimate the number of cavalrymen present in their squadrons on the field of battle and that the proportionate losses were, as a result, considerably higher than the official numbers might suggest.[70] The Union Brigade lost heavily in both officers and men killed (including its commander, William Ponsonby, and Colonel Hamilton the of the Scots Greys), and wounded. The 2nd Life Guards and the King's Dragoon Guards of the Household Brigade also lost heavily (with Colonel Fuller, commander of the King's DG, killed), though the 1st Life Guards, on the extreme right of the charge, and the Blues, who formed a reserve, had kept their cohesion, and suffered significantly fewer casualties. A counter-charge, by British and Dutch-Belgian light dragoons and hussars on the left wing and Dutch-Belgian carabiniers in the centre, repelled the French cavalry back to their positions.[71][72]

Many popular histories suggest that the British heavy cavalry were destroyed as a viable force following their first, epic charge. Examination of eyewitness accounts reveals, however, that far from being ineffective, they continued to provide very valuable services. They counter-charged French cavalry numerous times (both brigades),[73] halted a combined cavalry and infantry attack (Household Brigade only),[74][75] and were used to bolster the morale of those units in their vicinity at times of crisis, and to fill gaps in the Allied line caused by high casualties in infantry formations (both brigades).[76] This service was rendered at a very high cost, as close combat with French cavalry, carbine fire, infantry musketry and - more deadly than all of these - artillery fire steadily eroded the number of effectives[77] in the two brigades. At the end of the fighting, the two brigades could muster only a few composite squadrons.

Some 20,000 French troops had been committed to this attack. Its failure cost Napoleon not only heavy casualties — 3,000 prisoners were taken — but valuable time, as the Prussians now began to appear on the field to his right. Napoleon sent his reserve, Lobau's VI corps and two cavalry divisions, some 15,000 troops, to hold them back. With this, Napoleon had committed all of his infantry reserves, except the Guard, and he now had to beat Wellington not only quickly, but with inferior numbers.[78]

The French cavalry attack

A little before 16:00, Ney noted an apparent exodus from Wellington's centre. This was simply the movement to the rear of casualties from the earlier encounters, but he mistook this for the beginnings of a retreat, and sought to exploit it. Following the defeat of d'Erlon's Corps, Ney had few infantry reserves left, as most of the infantry been committed either to the futile Hougoumont attack or to the defence of the French right. Ney therefore tried to break Wellington's centre with his cavalry alone.[79] Initially Milhaud's reserve cavalry corps of cuirassiers and Lefebvre-Desnöettes' light cavalry division of the Imperial Guard, some 4,800 sabres, were committed. Following the repulse of their initial attack, Kellerman's heavy cavalry corps and Guyot's heavy cavalry of the Guard were added to the massed assault, and a total of around 9,000 cavalry were involved, in no less than sixty-seven squadrons.[80]

Wellington's army responded to this new attack by forming square - a formation four ranks deep and either literally a square or sometimes a rectangle formed with one of the longer sides facing towards the enemy. Squares were much smaller than usually depicted in paintings of the battle - a 500-man battalion square would have been no more than sixty feet (28.3m) in length on a side. Vulnerable to artillery or infantry, squares that stood their ground were deadly to cavalry, because they could not be outflanked and because horses would not charge into a hedge of bayonets. Wellington ordered his artillery crews, whose guns were dispersed along his line, to take shelter within the squares as the cavalry approached and to return to their guns and resume fire as they retreated.

Witnesses in the British infantry recorded suffering as many as twelve assaults, though this probably includes successive waves of the same general attack; the number of general assaults was undoubtedly far fewer. General Kellerman, apprehending the possible futility and wastefulness of the attacks, tried to reserve the elite carabinier brigade from joining in, though eventually Ney spotted them and enforced their involvement.[81]

A British eyewitness of the first French cavalry attack, an officer in the Foot Guards, recorded his impressions very lucidly and somewhat poetically:

About four P.M. the enemy's artillery in front of us ceased firing all of a sudden, and we saw large masses of cavalry advance: not a man present who survived could have forgotten in after life the awful grandeur of that charge. You discovered at a distance what appeared to be an overwhelming, long moving line, which, ever advancing, glittered like a stormy wave of the sea when it catches the sunlight. On they came until they got near enough, whilst the very earth seemed to vibrate beneath the thundering tramp of the mounted host. One might suppose that nothing could have resisted the shock of this terrible moving mass. They were the famous cuirassiers, almost all old soldiers, who had distinguished themselves on most of the battlefields of Europe. In an almost incredibly short period they were within twenty yards of us, shouting 'Vive l'Empereur!' The word of command, 'Prepare to receive cavalry,' had been given, every man in the front ranks knelt, and a wall bristling with steel, held together by steady hands, presented itself to the infuriated cuirassiers.

— Captain Rees Howell Gronow, Foot Guards, [82]

In essence this type of massed cavalry attack relied almost entirely on psychological shock for effect.[83] Close artillery support could disrupt infantry squares and allow cavalry to penetrate; at Waterloo, however, co-operation between the French cavalry and artillery was not impressive. The French artillery did not get close enough to the Anglo-allied infantry in sufficient numbers to be decisive.[84] Artillery fire between charges did produce mounting casualties, but most of this fire was at relatively long range and was often indirect, at targets beyond the ridge. If infantry being attacked held firm in their square defensive formations, and were not panicked, cavalry on their own could do very little damage to them. The French cavalry attacks were repeatedly repelled by the steadfast infantry squares, the harrying fire of British artillery as the French cavalry recoiled down the slopes to regroup, and the decisive counter-charges of the allied light cavalry regiments, the Dutch heavy cavalry brigade, and the remaining effectives of the Household Cavalry. At least one artillery officer disobeyed Wellington's order to seek shelter in the adjacent squares during the charges. Captain Mercer, who commanded G Troop, Royal Horse Artillery, thought the Brunswick troops on either side of him so shaky that he kept his battery of six 9-pounders in action throughout, to ruinous effect:

I thus allowed them to advance unmolested until the head of the column might have been about fifty or sixty yards from us, and then gave the word, "Fire!" The effect was terrible. Nearly the whole leading rank fell at once; and the round shot, penetrating the column carried confusion throughout its extent...the discharge of every gun was followed by a fall of men and horses like that of grass before the mower's scythe.

— Captain Cavalie Mercer, RHA, [85]

After numerous fruitless attacks on the allied ridge, the French cavalry was exhausted and depleted.[86]

Their overall casualties cannot easily be reckoned: the senior officers of the French cavalry, in particular the generals, experienced heavy losses. Four divisional commanders were wounded, nine brigadiers wounded, and one killed - testament to their courage and their habit of leading from the front.[87] Musters taken after the battle reflect not only combat losses on 16 June and 18 June, but also subsequent desertions, prisoners lost to the Allied pursuit, and wounded troopers still with the army but no longer among its effectives. Illustratively, however, Houssaye reports that the Grenadiers à Cheval numbered 796 of all ranks on 15 June, but just 462 on 19 June, while the Empress Dragoons lost 416 of 816 over the same period.[88] The combined loss rate for Guyot's Guard heavy cavalry division was 47%.

Eventually it became obvious, even to Ney, that the cavalry on their own were achieving little. Belatedly, Ney organised a combined-arms attack with troops from Reille's II Corps, using Bachelu's division and Tissot's regiment of Foy's division (about 6,500 infantrymen) plus those French cavalry that remained in a state fit to fight. This attack was directed towards the centre-right of Wellington's position, along much the same route as was taken by the French heavy cavalry earlier.[89] The assault was brought to a halt by a charge of the Household Brigade cavalry led by Uxbridge; however, the British cavalry could not break the French infantry formations, and consequently fell back having suffered from musketry fire.[90] Uxbridge then tried to lead the Dutch-Belgian heavy cavalry into the attack, but they refused to charge.[91] Meanwhile, Bachelu's and Tissot's men and their cavalry supports were being hard hit by fire from artillery and from Adam's infantry brigade, and eventually fell back themselves.[92] The Allied centre had not come out of the struggle with the French cavalry unscathed; though few casualties were caused to the infantry by the French cavalry directly, the artillery fire suffered by the infantry squares between cavalry attacks had been severe. Also the Allied cavalry, with the exception of Sir John Vandeleur's and Sir Hussey Vivian's brigades on the far left, had all been committed to the fight, and had taken casualties that eroded their subsequent effectiveness. The situation appeared so desperate that the Cumberland Hussars, the only Hanoverian cavalry regiment present, fled the field spreading alarm all the way to Brussels.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).

At approximately the same time as Ney's combined-arms assault on the centre-right of the Allied line, elements of D'Erlon's I Corps, spearheaded by the 13th Legere, renewed the attack on La Haye Sainte, and were ultimately successful. The fall of the farmhouse was partly due to the defenders running out of rifle ammunition.[93] Ney then moved horse artillery up towards the allied centre and began to pulverise the infantry squares at short-range with canister.[94] This took a severe toll of several regiments; the 27th Regiment was all but destroyed, and the 30th and 73rd Regiments suffered such heavy losses that they had to combine to form a viable square.

Arrival of the Prussian IV Corps: Plancenoit

The first Prussian corps to arrive was Bülow's IV Corps, whose objective was Plancenoit, which the Prussians intended to use it as a launch point into the rear of the French positions. It was Blücher's intention to secure his right upon Frichermont using the Bois de Paris road.[95] Blücher and Wellington had been exchanging communications since 10:00 am and had agreed to this advance on Frichermont if Wellington's centre was under attack.[96][97] General Bülow noted that the way to Plancenoit lay open and that the time was 16:30.[95] At about this time, as the French cavalry attack was in full spate, the 15th Brigade, IV Corps was sent to link up with the Nassauers of Wellington's left flank at Frichermont / La Haie area with the brigade's horse artillery battery and additional brigade artillery deployed to the left of the brigade in support.[98] Napoleon sent Lobau's Corps to intercept the rest of Bülow's IV Corps proceeding to Plancenoit. The 15th Brigade, in a separate action, threw Lobau's troops out of Frichermont with a determined bayonet charge. The 15th proceeded up the Frichermont heights battering French Chasseurs with 12-pounder artillery fire and pushed on to Plancenoit. This sent Lobau's Corps into retreat to the Plancenoit area, and in effect drove Lobau past the rear of the Armee Du Nord's right flank and directly threatened its only line of retreat. Napoleon had dispatched all eight battalions of the Young Guard to reinforce Lobau, who was now seriously pressed. Hiller's 16th Brigade had six battalions available, and pushed forward to attempt to take Plancenoit. The Young Guard counter-attacked and, after very hard fighting, secured Plancenoit, but were themselves counter-attacked and driven out.[78] Napoleon sent two battalions of the Middle/Old Guard into Plancenoit and after ferocious bayonet fighting - they did not deign to fire their muskets - this force recaptured the village.[78] The dogged Prussians were still not beaten, and approximately 30,000 troops of IV and II Corps, under Bülow and Pirch, attacked Plancenoit again. It was defended by 20,000 Frenchmen in and around the village.

Ziethen's flank march

Throughout the late afternoon, Graf von Ziethen's I Corps had been arriving in greater strength in the area just north of La Haie. Although ordered to march via Froidmont to Ohain, the troops instead marched northwest to Genval, putting much more distance between I Corps and IV Corps than had been allowed in the plan.[99] General Müffling, Prussian liaison to Wellington, rode to meet I Corps and found Ziethen's Chief of Staff, Oberstleutnant von Reiche. Müffling informed von Reiche that Wellington was desperate for Prussian assistance and could not hold on for long.[99] General Graf von Ziethen had by this time brought up the 1st Brigade, but had become concerned at the sight of stragglers and casualties, from the Nassau units on Wellington's left and the Prussian 15th Brigade. These troops appeared to be withdrawing, and Ziethen, fearing that his own troops would be caught up in a general retreat, was starting to move away from Wellington's flank and towards Plancenoit. General Müffling saw this movement away, and persuaded Ziethen to support Wellington's left flank. Ziethen resumed his march to support Wellington directly, and the arrival of his troops allowed Wellington to reinforce his crumbling centre by moving cavalry from his left.[100] I Corps attacked the French troops before Papelotte, relieving the pressure on Wellington's troops. By 19:30, the French position was bent into a rough horseshoe shape. The ends of the U were now based on Hougoumont on the French left, Plancenoit on the French right, and the centre on La Haie.[101] The French had retaken the positions of La Haie and Papelotte in a series of attacks by Durutte's division.[101] Oberst von Hofmann's 24th Regiment now led an advance towards La Haie and Papelotte; the French forces retreated behind Smohain without contesting the advance.[101] The 24th Regiment advanced against the new French position, but was seen off after some early success. Silesian Schützen (riflemen) and the F/1st Landwehr moved up in support as the 24th Regiment returned to the attack.[102] The French initially fell back before the renewed assault without much of an attempt at defence, but now began seriously to contest ground, attempting to regain Smohain and hold on to the ridgeline along Papelotte and the last few houses of Papelotte.[102] The 24th Regiment linked up with a Highlander battalion on its far right. Determined attacks by the 24th Regiment and the 13th Landwehr regiment with cavalry support threw the French out of these positions, and further attacks by the 13th Landwehr and the 15th Brigade expelled them from Frichermont.[103] Durutte’s division was beginning to unravel under the assaults when Ziethen’s I Corps cavalry poured through the gap.[104] Durutte's division, finding itself about to be charged by massed cavalry of Ziethen's I Corps cavalry reserve, retreated quickly from the battlefield. I Corps then attained the Brussels road and the only line of retreat available to the French.

Attack of the Imperial Guard

Meanwhile, with Wellington's centre exposed by the fall of La Haye Sainte, and the Plancenoit front temporarily stabilised, Napoleon committed his last reserve, the hitherto-undefeated Imperial Guard. This attack, mounted at around 19:30, was intended to break through Wellington's centre and roll up his line away from the Prussians. It is one of the most celebrated passages of arms in military history, but it is unclear which units actually participated. It appears that it was mounted by five battalions of the Middle Guard, and not by the Grenadiers or Chasseurs of the Old Guard. Three Old Guard battalions did move forward and formed the attack's second line, though they remained in reserve and did not directly assault the Allied line.[105] Marching through a hail of canister and skirmisher fire, the 3,000 or so Middle Guardsmen advanced to the west of La Haye Sainte, and in so doing, separated into three distinct attack forces. One, consisting of two battalions of Grenadiers, defeated Wellington's first line of British, Brunswick and Nassau troops. The Grenadiers marched on, and with the situation critical, Chassé's relatively fresh Netherlands division was sent forward. Chassé brought up his artillery to fire into the victorious grenadiers' flank. This still could not stop the Guard's advance, so Chassé ordered his first brigade to charge the outnumbered French, who faltered and broke. [106]

... I saw four regiments of the middle guard, conducted by the Emperor, arriving. With these troops, he wished to renew the attack, and penetrate the centre of the enemy. He ordered me to lead them on; generals, officers and soldiers all displayed the greatest intrepidity; but this body of troops was too weak to resist, for a long time, the forces opposed to it by the enemy, and it was soon necessary to renounce the hope which this attack had, for a few moments, inspired.

— Marshal M. Ney, [41]

Further to the west, 1,500 British Foot Guards under Maitland were lying down to protect themselves from the French artillery. As the second prong of the Imperial Guard's attack approached, consisting of two battalions of Chasseurs, Maitland's guardsmen rose as one, and devastated the shocked Imperial Guard with volleys of fire at point-blank range. The Chasseurs deployed to answer the fire, but after 10 minutes of exchanging musketry the outnumbered French began wavering. This was the sign for a bayonet charge, which broke the Chasseurs. At this point the third prong, a fresh Chasseur battalion, appeared on the scene. The British guardsmen retired with the French in pursuit, but the French in their turn were halted as the 52nd Light Infantry of Adam's brigade wheeled in line onto their flank and poured a devastating fire into them.[107] Under this onslaught they too broke.

The last of the Imperial Guard retreated headlong in disarray and chaos. A ripple of panic passed through the French lines as the astounding news spread - "La garde recule. Sauve qui peut!" ("The Guard retreats. Save yourself if you can!"). Wellington, judging that the retreat by the Imperial Guard had unnerved all the French soldiers who saw it, stood up in the stirrups of Copenhagen, and waved his hat in the air, signalling a general advance. The long-suffering allied infantry rushed forward from the lines where they had been shelled all day, and threw themselves upon the retreating French.[108]

After its unsuccessful attack on Wellington's centre, the surviving Imperial Guard rallied to their reserves of three battalions, (some sources say four) just south of La Haye Sainte for a last stand against the British. A charge from General Adam's Brigade and an element of the 5th Brigade (The Hanoverian Landwehr Osnabruck Battalion), both in the second allied division under Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton, plus, to their right, Vivian's and Vandeleur's relatively fresh cavalry brigades, threw them into a state of confusion; those which were left in semi-coherent units fought and retreated towards La Belle Alliance. It was during this stand that Colonel Hugh Halkett asked the surrender of General Cambronne. It was probably during the destruction of one of the retreating semi-coherent squares from the area around La Haye Sainte towards La Belle Alliance that the famous retort to a request to surrender was made "La Garde meurt, elle ne se rend pas!" ("The Guard dies, it does not surrender!").[109][110]

Capture of Plancenoit

At about the same time, the Prussians were starting to pushing through Plancenoit, in the third assault of the day upon the town.[104] The Prussian 5th, 14th, and 16th Brigades were involved in the attack.[104] The church was by now on fire, flames roaring out of every window and door. All the horrors of 19th century urban warfare were on display, with house-to-house fighting leaving bodies from both sides lying about. The central graveyard and the French centre of resistance had corpses strewn about "as if by a whirlwind".[111] The French Guard battalions, a Guard Chasseur and 1/2e Grenadiers, were holding the position, while three more Old Guard battalions were behind Plancenoit, serving to link the Plancenoit position to the rest of the French army, and guarding the last line of retreat off the battlefield. Virtually all of the Young Guard was now involved in the defence, along with remnants of Lobau's Corps.[104] The key to the position proved to be the woods to the south of Plancenoit. Pirch's II Corps had arrived with two brigades and reinforced the attack of IV Corps, attacking through the Chantelet woods directly to the south. The 25th Regiment's musketeer battalions threw the 1/2e Grenadiers (Old Guard) out of the Chantelet woods, outflanking Plancenoit and forcing a retreat. The French Old Guard battalions retreated in good order and reluctance until they met the mass of troops retreating in panic, and became part of that rout. [104] The Prussian IV Corps advanced beyond Plancenoit to find masses of French retreating in a jumbled mass from pursuing British units.[111] The Prussians were unable to fire for fear of hitting allied units. It was now seen that the French right, left, and centre, had failed.[111]

Disintegration

The whole of the French front started to disintegrate under the general advance of Wellington's army and the Prussians following the capture of Plancenoit.[112] The last coherent French force consisted of two battalions of the Old Guard stationed around the inn called La Belle Alliance. This was a final reserve and a personal bodyguard for Napoleon. For a time, Napoleon hoped that if they held firm, the French army could rally behind them.[113] But as the retreat turned into a rout, they were forced to withdraw and form squares as protection against the leading elements of allied cavalry. They formed two squares, one on either side of La Belle Alliance. Until he was persuaded that the battle was lost and he should leave, Napoleon commanded the square which was formed on rising ground to the (French) left of the inn.[114][115] The Prussians engaged the square to the (French) right, and General Adam's Brigade charged the square on the (French) left, forcing it to withdraw.[116] As dusk fell, both squares retreated away from the battlefield towards France in relatively good order, but the French artillery and everything else fell into the hands of the Allies and Prussians. The retreating Guards were surrounded by thousands of fleeing Frenchmen who were no longer part of any coherent unit. Allied cavalry harried the fleeing French until about 23:00. The Prussians, led by General von Gneisenau, pursued them as far as Genappe before ordering a halt. By that point, some 78 guns had been captured along with about 2,000 prisoners, including more generals.[117] At Genappe, Napoleon's carriage was found abandoned still containing diamonds left in the rush. These became part of King Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia's crown jewels, one Major Keller of the F/15th receiving the Pour le Mérite with oak leaves for the feat.[118]

There remained to us still four squares of the Old Guard to protect the retreat. These brave grenadiers, the choice of the army, forced successively to retire, yielded ground foot by foot, till, overwhelmed by numbers, they were almost entirely annihilated. From that moment, a retrograde movement was declared, and the army formed nothing but a confused mass. There was not, however, a total rout, nor the cry of sauve qui peut, as has been calumniously stated in the bulletin.

— Marshal M. Ney, [119]

In the middle of the position occupied by the French army, and exactly upon the height, is a farm, called Le Belle Alliance. The march of all the Prussian columns was directed towards this farm, which was visible from every side. It was there that Napoleon was during the battle; it was thence that he gave his orders, that he flattered himself with the hopes of victory; and it was there that his ruin was decided. There, too, it was, that by happy chance, Field Marshal Blucher and Lord Wellington met in the dark, and mutually saluted each other as victors.

— General Gneisenau, [120]

Aftermath

Peter Hofschröer has written that Wellington and Blücher met at Genappe around 22:00 signifying the end of the battle.[118] Other sources have recorded that the meeting took place around 21:00 near Napoleon's former headquarters La Belle Alliance.[121] Waterloo cost Wellington around 15,000 dead and wounded, and Blücher some 7,000. Napoleon lost 25,000 dead and injured, with 8,000 taken prisoner.

June 22. This morning I went to visit the field of battle, which is a little beyond the village of Waterloo, on the plateau of Mont St Jean; but on arrival there the sight was too horrible to behold. I felt sick in the stomach and was obliged to return. The multitude of carcasses, the heaps of wounded men with mangled limbs unable to move, and perishing from not having their wounds dressed or from hunger, as the Allies were, of course, obliged to take their surgeons and waggons with them, formed a spectacle I shall never forget. The wounded, both of the Allies and the French, remain in an equally deplorable state.

— Major W. E Frye After Waterloo: Reminiscences of European Travel 1815-1819.[122]

After the French defeat at Waterloo, the simultaneous Battle of Wavre, was concluded 12 hours later. The armies of Wellington and Blucher and other Coalition forces advanced upon Paris. In the final skirmish of the Napoleonic Wars, Marshal Davout, Napoleon's minister of war, was defeated by Blücher at Issy on 3 July 1815.[123] With this defeat, all hope of holding Paris faded, and Napoleon announced his abdication 24 June 1815. Allegedly, Napoleon tried to escape to North America but the Royal Navy was blockading the French ports to forestall such a move. He finally surrendered to the captain of HMS Bellerophon on 15 July. There was a campaign against hold out French fortresses that ended with the capitulation of Longwy on 13 September 1815. The Treaty of Paris was signed on 20 November, 1815. Louis XVIII was restored to the throne of France, and Napoleon was exiled to Saint Helena, where he died in 1821.[124]

Royal Highness, - Exposed to the factions which divide my country, and to the emnity of the great Powers of Europe, I have terminated my political career; and I come, like Themistocles, to throw myself upon the hospitality (m'asseoir sur le foyer) of the British people. I claim from your Royal Highness the protections of the laws, and throw myself upon the most powerful, the most constant, and the most generous of my enemies.

— Napoleon. (letter of surrender to the Prince Regent; translation), [41]

Waterloo was a decisive battle in more than one sense. It definitively ended the series of wars that had convulsed Europe, and involved many other regions of the world, since the French Revolution of the early 1790s. It also ended the political and military career of Napoleon Bonaparte, one of the greatest commanders and statesmen in history. Finally, it ushered in almost half a century of international peace in Europe; no major conflict was to occur until the wars resulting from the unifications of Germany and Italy in the latter half of the 19th century.

Maitland's 1st Foot Guards, who had defeated the Chasseurs of the Guard, were thought to have defeated the Grenadiers; they were awarded the title of Grenadier Guards in recognition of their feat, and adopted bearskins in the style of the Grenadiers. Britain's Household Cavalry likewise adopted the cuirass in recognition of their success against their armoured French counterparts. The effectiveness of the lance was noted by all participants and this weapon subsequently became the preferred weapon of all cavalry, whatever their technical title.

The battlefield today

The current terrain of the battlefield is very different from how it appeared in 1815. Tourism began the day after the battle, with Captain Mercer noting that on the 19th June "a carriage drove on the ground from Brussels, the inmates of which, alighting, proceeded to examine the field." [125]. In 1820, the Netherlands' King William I ordered the construction of a monument on the spot where it was believed his son, the Prince of Orange, had been wounded. The Lion's Hillock, a giant mound, was constructed here, using 300,000 cubic metres (392,000 cu yd) of earth taken from other parts of the battlefield, including Wellington's sunken road.

Every one is aware that the variously inclined undulations of the plains, where the engagement between Napoleon and Wellington took place, are no longer what they were on June 18, 1815. By taking from this mournful field the wherewithal to make a monument to it, its real relief has been taken away, and history, disconcerted, no longer finds her bearings there. It has been disfigured for the sake of glorifying it. Wellington, when he beheld Waterloo once more, two years later, exclaimed, "They have altered my field of battle!" Where the great pyramid of earth, surmounted by the lion, rises to-day, there was a hillock which descended in an easy slope towards the Nivelles road, but which was almost an escarpment on the side of the highway to Genappe. The elevation of this escarpment can still be measured by the height of the two knolls of the two great sepulchres which enclose the road from Genappe to Brussels: one, the English tomb, is on the left; the other, the German tomb, is on the right. There is no French tomb. The whole of that plain is a sepulchre for France.

— Victor Hugo, Les Miserables, [126]

See also

References

- Adkin, Mark (2001). The Waterloo Companion. Aurum. ISBN 1-85410-764-X

- Barbero, Alessandro (2005). The Battle: A New History of Waterloo. Atlantic Books. ISBN 1-84354-310-9

- Beamish, N. Ludlow (1832, reprint 1995). History of the King's German Legion. Dallington: Naval and Military Press. ISBN 0-952201-10-0

- Booth, John (1815). The Battle of Waterloo: Containing the Accounts Published by Authority, British and Foreign, and Other Relevant Documents, with Circumstantial Details, Previous and After the Battle, from a Variety of Authentic and Original Sources. available on Google Books

- Chandler, David G. (1973). Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-02523-660-1

- Chesney, Charles C. (1907). Waterloo Lectures: A Study Of The Campaign Of 1815. Longmans, Green, and Co. ISBN 1428649883

- Count Drouet. Drouet's account of Waterloo to the French Parliament. napoleonbonaparte.nl. Retrieved on September 14 2007.

- Creasy, Sir Edward (1877). The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World: from Marathon to Waterloo. Richard Bentley & Son. ISBN 0-30680-559-6

- Fitchett, W. H. (1897, reprint 1921 & 2006). Deeds that Won the Empire. Historic Battle Scenes, Joun Murry & Project Gutenberg

- Frye, W. E. After Waterloo: Reminiscences of European Travel 1815-1819, Project Gutenberg

- Gleig, George Robert (ed) (1845). The Light Dragoon. London: George Routledge & Co.

- Glover, Gareth (2004). Letters from the Battle of Waterloo. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1853675970

- Gronow, R. H. (1862). Reminiscences of Captain Gronow London. ISBN 1-40432-792-4

- Houssaye, Henri. Waterloo, London, 1900.

- Kincaid, Captain J., Rifle Brigade. Waterloo, 18 June 1815: The Finale. iprimus.com.au. Retrieved on September 14 2007.

- Longford, Elizabeth (1971). Wellington the Years of the Sword. London: Panther. ISBN 0-58603-548-6

- Hofschröer, Peter (1815). The Waterloo Campaign: The German Victory. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-368-4

- Hugo, Victor. Les Miserables Chapter VII: Napoleon in a Good Humor. The Literature Network. Retrieved on September 14 2007.

- Mercer, A.C. "Waterloo, 18 June 1815: The Royal Horse Artillery Repulse Enemy Cavalry, late afternoon". Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- Parry, D.H. (1900). Waterloo from Battle of the nineteenth century, Vol. 1. London: Cassell and Company. Retrieved on September 14 2007.

- Roberts, Andrew (2005). Waterloo: June 18, 1815, the Battle for Modern Europe. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-008866-4

- Siborne, H.T. (1891, reprint 1993). The Waterloo Letters. New York & London: Cassell & Greenhill Books. ISBN 1853671568

- Siborne, William (1844, reprint 1894 & 1990). The Waterloo Campaign. Birmingham. 4th edition. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1853670693

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Greenhill Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London & Pennsylvania: Greenhill Books & Stackpole Books. ISBN 1-85367-276-9

- Weller, J. (1992). Wellington at Waterloo, London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85376-339-0

- Wellesley, Arthur Wellington's Dispatches June 19th, 1815. War Times Journal Archives.

- White, John. Cambronne's Words Letters to The Times (June 1932). NapoleonSeries.org. Retrieved on September 14 2007.

Notes

- ^ Barbero, p. 420

- ^ Barbero, p. 419.

Wellington's army: 3,500 dead; 10,200 wounded; 3,300 missing.

Blücher's army: 1,200 dead; 4,400 wounded; 1,400 missing. - ^ Wikiquote:Wellington citing Creevey Papers, ch. x, p. 236

- ^ Timeline: The Congress of Vienna, the Hundred Days, and Napoleon's Exile on St. Helena, Center of Digital Initiatives, Brown University Library

- ^ Hamilton-Williams, David p. 59

- ^ Chandler

- ^ Hofschroer, Waterloo Campaign Ligny and Quatre Bras p. 136-160

- ^ Longford, p. 508

- ^ Longford, p. 527

- ^ Chesney, p. 136

- ^ a b c Chesney, p. 136

- ^ Barbero, p. 75

- ^ Longford, p. 485

- ^ Longford, p. 484

- ^ Barbero, pp. 75-76

- ^ Mercer

An artillery captain, Mercer, thought the Brunswickers "perfect children". - ^ Longford, p. 486

On 13 June, the commandant at Ath requested powder and cartridges as members of a Hanoverian reserve regiment there had never yet fired a shot. - ^ Barbero, p. 39

- ^ Hofschroer, Waterloo Campaign Ligny and Quatre Bras p. 59

- ^ Hofschroer, Waterloo Campaign Ligny and Quatre Bras p. 60-62

- ^ Barbero, p. 21

- ^ Barbero, pp. 78-79

- ^ Barbero, p. 80

- ^ Barbero, p. 149

- ^ Barbero, pp. 141, 235

- ^ Barbero, pp. 83-85.

- ^ Barbero, p. 91

- ^ Longford, pp. 535-536

- ^ Barbero, p. 141

- ^ Longford, p. 547

- ^ Barbero, p. 73

- ^ Longford, p. 548

- ^ Barbero, pp. 95-98

- ^ Wellesley

- ^ Fitchett

"The hour at which Waterloo began, though there were 150,000 actors in the great tragedy, was long a matter of dispute. The Duke of Wellington puts it at 10:00. General Alava says half-past eleven, Napoleon and Drouet say noon, and Ney 13:00. Lord Hill may be credited with having settled this minute question of fact. He took two watches with him into the fight, one a stop-watch, and he marked with it the sound of the first shot fired, and this evidence is now accepted as proving that the first flash of red flame which marked the opening of the world-shaking tragedy of Waterloo took place at exactly ten minutes to twelve." - ^ Roberts, p. 55

- ^ That is, the 1st battalion of the 2nd Regiment. Among Prussian regiments, "F/12th" would denote the fusilier battalion of the 12th Regiment.

- ^ Barbero, pp. 113-114

- ^ Napoleonic: The Great Gate of Hougoumont (Image). MilitaryCompany.com. Retrieved on September 14 2007.

- ^ Barbero, p. 298

Seeing the flames, Wellington sent a note to the house's commander stating that he must hold his position whatever the cost, - ^ a b c Booth, p. 10 Cite error: The named reference "BoothAccounts" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Creasy, chapter XV

- ^ See, for example, Longford, pp. 552-554

- ^ Barbero, p. 298

- ^ Barbero, pp. 305-306

- ^ Fitchett, "Lord Hill may be credited with having settled this minute question of fact. He took two watches with him into the fight, one a stop-watch, and he marked with it the sound of the first shot fired ... At ten minutes to twelve the first heavy gun rang sullenly from the French ridge"

- ^ Barbero p. 131

- ^ a b Barbero, p. 130

- ^ Barbero, p. 136

- ^ Barbero, p. 145

- ^ Barbero, p. 165

- ^ Barbero, p. 164

- ^ Barbero, pp. 166-168

- ^ Barbero, p. 177

- ^ Longford, p. 556

The Dutch were booed by some units as they left the battlefield, though some disagreed with this as they thought that they might be more Bonapartists than cowards. - ^ Barbero, p. 174

- ^ a b Barbero, pp.185-187

- ^ Barbero, p. 188

Three for the Household Brigade and none for the Union out of nineteen squadrons in total. - ^ Siborne, W., Letter 5

- ^ Glover, Letter 16

The total may have been 18 squadrons as there is an uncertainty in the sources as to whether the King's Dragoon Guards fielded three or four squadrons. There is evidence that Uxbridge gave an order, the morning of the battle, to all cavalry brigade commanders to commit their commands on their own initiative, as direct orders from himself might not always be forthcoming, and to "support movements to their front". It appears that Uxbridge expected the brigades of Vandeleur, Vivian and the Dutch-Belgian cavalry to provide support to the British heavies. - ^ Barbero, note 18, p. 426

An episode famously used later by Victor Hugo in Les Miserables. - ^ Siborne, W., pp. 410-411.

- ^ Houssaye, p. 182

- ^ This anecdote can be found in The Waterloo Papers by E. Bruce Low contained in With Napoleon at Waterloo, MacBride, M., (editor), London 1911. The tale was related, in old age, by a Sgt Major Dickinson of the Greys, reputedly the last survivor of the charge.

- ^ Barbero, pp. 198-204

- ^ Barbero, p. 211

- ^ Siborne, W., pp. 425-426.

- ^ Adkin, p. 217 (for initial strengths)

- ^ Smith, p. 544 (for losses)

Losses are ultimately from the official returns taken the day after the battle: Household Brigade, initial strength 1,319, killed - 95, wounded - 248, missing - 250, totals - 593, horses lost - 672. Union Brigade, initial strength 1,332, killed - 264, wounded - 310, missing - 38, totals - 612, horses lost - 631. - ^ This view appears to have arisen from a comment by Captain Clark-Kennedy of the 1st Dragoons 'Royals,' in a letter in H. W. Siborne's book, he makes an estimate of around 900 men actually in line within the Union Brigade before its first charge. He does not, however, explain how his estimate was arrived at. The shortfall of 432 men (the equivalent of a whole regiment) from the paper strength of the brigade is large.

- ^ Siborne, W., pp. 329, 349 (composition of brigades), pp. 422-424 (actions of brigades)

Note: William Siborne was in possession of a number of eyewitness accounts from generals, such as Uxbridge, down to cavalry cornets and infantry ensigns. This makes his history particularly useful (though only from the British and KGL perspective); some of these eyewitness letters were later published by his son, a British Major General (H.T. Siborne)). - ^ Barbero, pp. 219-223

- ^ Siborne, H.T., Letters: 18, 26, 104

- ^ Siborne, H.T., p. 38

- ^ Siborne, W., p. 463

- ^ Siborne, H.T., Letters 9, 18, 36

- ^ In a cavalry unit an "effective" was an unwounded trooper mounted on a sound horse. The military term 'effective' describes a soldier, piece of equipment (eg. a tank or aircraft) or military unit capable of fighting or carrying out its intended purpose.

- ^ a b c Hofschröer, p. 122

- ^ Siborne, W., p. 439

- ^ Adkin, p. 356

- ^ Adkin, p. 359

- ^ Gronow

- ^ Weller, pp. 211-212

- ^ Adkin, pp. 252, 361

- ^ Mercer

- ^ Weller, p. 114

- ^ Adkin, p. 359

- ^ Houssaye, p. 522

- ^ Adkin, p.361

- ^ Siborne, H.T., pp. 14, 38-39

- ^ Siborne, H.T., pp. 14-15

- ^ Adkin, p. 361

- ^ Beamish, p. 367

- ^ Siborne, W., p. 439

- ^ a b Hofschröer, p. 116

- ^ Hofschröer, p. 95

- ^ Chasney, p. 165

- ^ Hofschröer, p. 117

- ^ a b Hofschröer, p. 124

- ^ Hofschröer, p. 125

- ^ a b c Hofschröer, p. 139

- ^ a b Hofschröer, p. 140

- ^ Hofschröer, p. 141

- ^ a b c d e Hofschröer, p. 144

- ^ Adkin p. 391

The attacking battalions were 1st/3rd and 4th Grenadiers and 1st/3rd, 2nd/3rd and 4th Chasseurs of the Middle Guard; those remaining in reserve were the 2nd/2nd Grenadiers, 2nd/1st and 2nd/2nd Chasseurs of the Old Guard. - ^ Chesny, p. 178

- ^ Chesny, p. 179

- ^ Chesny, p. 179

- ^ White

The retort to a request to surrender may have been "La Garde meurt, elle ne se rend pas!" ("The Guard dies, it does not surrender!") or the response may have been the more earthy "Merde!", but Letters published in The Times in June 1932 record that Cambronne said neither, as he was already a prisoner (held securely by the aiguillette, decorative shoulder cords, by Halkett in person), but that they may have been said by General Michel who was killed at Waterloo. - ^ Parry

- ^ a b c Hofschröer, p. 145

- ^ Hofschröer, p. 146

- ^ Kincaid

- ^ Count Drouet

- ^ Creasy, Chapter XV. Battle of Waterloo, A.D. 1815

Fifteen decisive battles of the world from Marathon to Waterloo. - ^ Hofschröer, p. 149

- ^ Hofschröer, p. 150

- ^ a b Hofschröer, p. 151

- ^ Booth, p. 74

- ^ Booth, p. 23

- ^ Battle of Waterloo on the website of the British Ministry of Defence. See the link near the bottom called "here" (ppt) Slide 39

- ^ Frye

- ^ Nuttal Encyclopaedia: Issy

- ^ Hofschröer, pp. 274-276, 320

- ^ Captain Cavalie Mercer, RHA

- ^ Hugo

Further reading

- Articles

- Anonymous. Napoleon's Guard at Waterloo 1815

- Hofschröer, Peter. The Prussians and Wellington at Waterloo (Questions to Peter Hofschroer supplied by our visitors)

- Lichfield, John. Waterloo's significance to the French and British - including proportions of soldiers by nation The Independent, 17 November 2004

- Staff, Battle of Waterloo a British regimental account on the The Rifles web site

- Staff, Empire and Sea Power: The Battle of Waterloo BBC History, 9 June 2006

- Books

- Chesney, Charles C. (1997). Waterloo Lectures. London: Greenhill Books. Rep Sub edition. ISBN 1-85367-288-2

- Glover, Michael (1973). The Napoleonic Wars: An Illustrated History, 1792-1815. Hippocrene Books New York; ISBN 0-882-54473-X

- Hofschröer, Peter (2004). Wellington's Smallest Victory: The Duke, the Model Maker and the Secret of Waterloo. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-21769-9

- Howarth , David (2003). Waterloo - A Near Run Thing. Phoenix Press. ISBN 1-842-12719-5

- Maps

- Map of the battlefield

- Battle of Waterloo maps and diagrams

- Map of the battlefield on modern Google map and satellite photographs showing main locations of the battlefield

- Primary sources

- Cook, Christopher. Eye witness accounts of Napoleonic warfare

- Staff Official website of Waterloo Battlefield

- Staff, The Waterloo Medal Book: Recipients of the Waterloo medal in The National Archives: UK government records and information management