Trombone

| |

| Classification | |

|---|---|

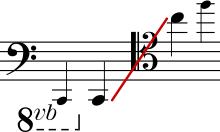

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| More articles or information | |

|

List of classical trombonists List of jazz trombonists | |

The trombone is a musical instrument in the brass family. Like all brass instruments, it is a lip-reed aerophone; sound is produced when the player’s vibrating lips (embouchure) cause the air column inside the instrument to vibrate. The trombone is usually characterized by a telescopic slide with which the player varies the length of the tube to change pitches, although the less common valve trombone uses three valves similar to those on a trumpet.

The word trombone derives from Italian tromba (trumpet) and -one (a suffix meaning "large"), so the name literally means "large trumpet". Trombones and trumpets share the important characteristic of having predominantly cylindrical bores. Therefore, the most frequently encountered trombones — the tenor and bass trombone — are the tenor and bass counterparts of the trumpet. They are both pitched in B♭ — with the slide all the way in, the notes of the harmonic series based on B♭ can be played — but trombones generally read music in concert pitch.

A person who plays the trombone is referred to as a trombonist.

Construction

|

|

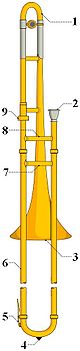

The trombone consists of a cylindrical tube bent into an elongated "S" shape in a complex series of tapers, the smallest being at the mouthpiece receiver, and the largest being at the throat of the bell, before the flare for the bell begins. (Careful design of these tapers is crucial to the intonation of the instrument.) As with other brass instruments, sound is produced by blowing air through pursed lips producing a vibration that creates a standing wave in the instrument.

The detachable cup-shaped mouthpiece, similar to that of the baritone, closely related to that of the trumpet, is inserted into the mouthpiece receiver in the slide section, which consists of a leadpipe, inner and outer slide tubes, and bracing, known as inner and outer slide stays. While modern stays are soldered, sackbuts (a medieval precursor to the trombone) were made with loose, unsoldered stays, which remained the pattern for German trombones until the mid-20th century. The leadpipe contains the venturi, which is a small constriction of the air column, adding a certain amount of resistance and to a great extent dictating the tone of the instrument; leadpipes may be soldered in permanently or interchangeable, depending on the maker.

The telescopic 'slide', the defining feature of the trombone (cf. valve trombone) allows the player to extend the length of the air column, lowering the pitch. In order to prevent friction from slowing the action of the slide, additional sleeves were developed during the Renaissance and these stockings were soldered onto the ends of the inner slide tubes. Nowadays, the stockings are incorporated into the manufacturing process of the inner slide tubes and represent a fractional widening of the tube to accommodate the necessary method of alleviating friction. This part of the slide must be lubricated on a frequent basis. Additional tubing connects the slide to the bell of the instrument through a neckpipe, and bell or back bow (U-bend). The joint connecting the slide and bell sections is furnished with a ferrule to secure the connection of the two parts of the instrument, though older models from the early 20th century and before were usually equipped with friction joints and no ancillary mechanism to tighten the joint.

The adjustment of intonation is most often accomplished with a tuning slide that is a short slide between the neckpipe and the bell incorporating the bell bow (U-bend); this device was designed by the French maker François Riedlocker during the early nineteenth century and applied to French and British designs and later in the century to German and American models, though German trombones were built without tuning slides well into the 20th century. However, trombonists, unlike other instrumentalists, are not subject to the intonation issues connected with valved or keyed instruments, and as such can adjust intonation "on the fly" by adjusting the slide positions, as need be.

As with the trumpet, the trombone is considered a cylindrical bore instrument since it has extensive sections of tubing, principally in the slide section, that are of continuous diameter. This is in contrast to conical bore instruments like the cornet, euphonium, and tuba, whose only cylindrical tubing is in the valve section. Tenor trombones typically have a bore of 0.450" (small bore) to 0.547" (large or orchestral bore) after the leadpipe and through the slide. The bore expands through the backbore to the bell which is typically between 7" and 8½". A number of common variations on trombone construction are noted below.

History

Until the early 18th century, the trombone was called the sackbut in English, a word with various different spellings ranging from sackbut to shagbolt and derived from the Spanish sacabuche or French sacqueboute. This was not a distinct instrument from the trombone, but rather a different name used for an earlier form. Other countries used the same name throughout the instrument's history, viz. Italian trombone and German Posaune. The sackbut was built in slightly smaller dimensions than modern trombones, and had a bell that was more conical and less flared. Today, sackbut is generally used to refer to the earlier form of the instrument, commonly used in early music ensembles. Sackbuts were (and still are) made in every size from soprano to contrabass, though then, as now, the contrabass was rare.

Renaissance and Baroque periods

The trombone was used frequently in 16th century Venice in canzonas, sonatas, and ecclesiastical works by Andrea Gabrieli and his nephew Giovanni Gabrieli, and also later by Heinrich Schütz in Germany. While the trombone was used continuously in Church music and in some other settings (i.e., as an addition to the opera house orchestra or to represent the supernatural or the funerary) from the time of Claudio Monteverdi onwards, it remained rather rare in the concert hall until the 19th century. During the Baroque period, Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel used the trombone on few occasions; Bach used it in combination with the cornett to evoke the stile antico in some of his many cantatas and Handel used it in the Dead March from Saul, Samson, and Israel in Egypt, all of which were examples of a new oratorio style popular during the early 18th century.

Classical period

The repertoire of trombone solo and chamber literature has its beginnings in Austria in the Classical Era where composers such as Leopold Mozart, Georg Christoph Wagenseil, Johann Albrechtsberger and Johann Ernst Eberlin were featuring the instrument, often in partnership with a voice. Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart used the trombones in a number of their sacred works, including two extended duets with voice from Mozart, the best known being in the Tuba Mirum of his Requiem. The inspiration for many of these works was no doubt the virtuosic playing of Thomas Gschladt who worked in the court orchestra at Salzburg, although when his playing faded, so did the general composing output for the instrument. The trombone retained its traditional associations with the opera house and the Church during the 18th century and was usually employed in the usual alto/tenor/bass trio to support the lower voices of the chorus, though Viennese court orchestra Kapellmeister Johann Joseph Fux rejected an application from a bass trombonist in 1726 and restricted the use of trombones to alto and tenor only, which remained the case almost until the turn of the 19th century in Vienna, after which time a second tenor trombone was added when necessary. The construction of the trombone changed relatively little between the Baroque period and Classical period with the most obvious feature being the slightly more flared bell than was previously the custom.

The first use of the trombone in a symphony was in 1807 in the Symphony in E♭ by the Swedish composer Joachim Nicolas Eggert 1, although the composer usually credited with its introduction into the symphony orchestra was Ludwig van Beethoven, who used it in the last movement of his Symphony No. 5 in C minor (1808). Beethoven also used trombones in his Symphony No. 6 in F major ("Pastoral") and Symphony No. 9 ("Choral").

Romantic period

Leipzig became a centre of trombone pedagogy; the trombone began to be taught at the new Musikhochschule founded by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. Mendelssohn's bass trombonist, Karl Traugott Queisser, was the first in a long line of distinguished professors of trombone at the academy in Leipzig and several composers penned works for him, including Ferdinand David (Mendelssohn's concertmaster), Ernst Sachse and Friedrich August Belcke, whose solo works all remain popular today in Germany. Queisser almost single-handedly helped to re-establish the reputation of the trombone in Germany and began a tradition in trombone-playing that is still practised there today. He championed and popularised Christian Friedrich Sattler's new tenorbass trombone during the 1840s, leading to its widespread use in orchestras throughout Germany and Austria. Sattler's influence on trombone design is not to be underestimated; he introduced a significant widening of the bore (the most important since the Renaissance), the innovations of Schlangenverzierungen (snake decorations), the bell garland and the wide bell flare, all of which are features that are still to be found on German-made trombones today and were widely copied during the 19th century.

Many composers were directly influenced by Beethoven's use of trombones, and the 19th century saw the trombones become fully integrated in the orchestra, particularly by the 1840s, as composers such as Franz Schubert, Franz Berwald, Johannes Brahms, Robert Schumann, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Richard Wagner, Hector Berlioz, Gioacchino Rossini, Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini, Franz Liszt, Richard Strauss, Anton Bruckner, Gustav Mahler, Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Alexander Borodin, Bedřich Smetana, Antonín Dvořák, Charles Gounod, César Franck, Claude Debussy, Camille Saint-Saëns and many others included trombones in their operas, symphonies and other orchestral compositions.

The 19th century also saw the erosion of the traditional alto/tenor/bass trombone trio in the orchestra. While the alto/tenor/bass trombone trio had been paired with one or two cornetts during the Renaissance and early Baroque periods, the disappearance of the cornett as a partner and eventual replacement by oboe and clarinet did not fundamentally alter the raison d'être for the trombones, which was to support the alto, tenor and bass voices of the chorus (typically in an ecclesiastical setting), whose harmonic moving lines were more difficult to pick out than the melodic soprano line. The introduction of the trombones into the orchestra, however, allied them more closely with the trumpets and it did not take long for the alto and bass trombones to be replaced by tenor trombones, although the Germans and Austrians held on to the alto trombone and F or E♭ bass trombone somewhat longer than the French, who came to prefer a section of three tenor trombones until after the Second World War.

By the time the trombone gained a regular footing in the orchestra, players of the instrument were no longer usually employed by a cathedral or court orchestra and were therefore expected to provide their own instrument. Military musicians were provided with instruments by the army and instruments like the long F or E♭ bass trombone remained in use there until approximately the time of the First World War, but the orchestral musician understandably adopted the instrument with the widest range which could be most easily applied to play any of the three trombone parts usually scored in any given work - the tenor trombone. The appearance of the valve trombone during the mid-19th century did little to alter the make-up of the trombone section in the orchestra and though it remained popular almost entirely to the exclusion of the slide instrument in countries such as Italy and Bohemia, the valve trombone was ousted from orchestras in Germany and France. The valve trombone continued to enjoy an extended period of popularity in Italy and Bohemia and composers such as Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini, Bedřich Smetana and Antonín Dvořák scored for a section of valve trombones.

Especially with the ophicleide or later the tuba subjoined to the trombone trio during the 19th century, parts scored for the bass trombone rarely descended as low as the parts scored before the addition of either of these new low brass instruments; only in the early 20th century did it regain a degree of independence. Experiments with different constitutions of the trombone section during the 19th and early 20th centuries, including Richard Wagner's addition of a contrabass trombone in Der Ring des Nibelungen and Gustav Mahler's and Richard Strauss' occasional augmentation by adding a second bass trombone to the usual trio of two tenor trombones and one bass trombone, have not had any lasting effect; the vast majority of orchestral works are still scored for the usual mid- to late-19th-century low brass section of two tenor trombones, one bass trombone and one tuba.

Twentieth century

In the 20th Century the trombone maintained its important position in the orchestra with prominent parts in works by Richard Strauss, Gustav Mahler, Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, Maurice Ravel, Darius Milhaud, Olivier Messiaen, Igor Stravinsky, Dmitri Shostakovich, Sergei Rachmaninov, Sergei Prokofiev, Ottorino Respighi, Edward Elgar, Gustav Holst, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Benjamin Britten, William Walton, Jean Sibelius, Carl Nielsen, Leoš Janáček, George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein and Béla Bartók.

In the second half of the century, new composers began giving back to the trombone a level of importance in solo and chamber music. Pieces such as Edgard Varèse's Octandre, Paul Hindemith's Sonata and Luciano Berio's Sequenza V led the way for lesser-known composers to build a wider repertoire. Popular choices for recital music today include Stjepan Sulek's Vox Gabrieli, Jacques Casterède's Sonatine and Jean Michel Defaye's Deux Danses. The best known trombone concertos from this period include works by Derek Bourgeois, Lars-Erik Larsson, Launy Grøndahl, Jan Sandström and Gordon Jacob.

Numerous changes in construction have occurred during the 20th century, including the use of different materials, increases in mouthpiece, bore and bell dimensions, new valve types and different mute types.

Today, the trombone can usually be found in wind ensembles/concert bands, symphony orchestras, marching bands, military bands, brass bands, brass choirs, etc. It can be part of smaller groups as well, such as brass quintets, quartets, or trios, or trombone trios, quartets, or choirs (though the size of a trombone choir can vary greatly from five or six to twenty or more members). Trombones are also common in swing, jazz, merengue, salsa (prominent example: Jimmy Bosch), rock (Bill Reichenbach and James Pankow serving as two prominent examples), R&B, and ska (prominent example: Don Drummond). It is in jazz and swing music that it has arguably made the greatest advances since the turn of the 20th century with famous artists such as Ray Anderson, Tommy Dorsey, Delfeayo Marsalis, Miff Mole, Joe Nanton, Louis Satterfield, Reggie Young, Carl Fontana, Curtis Fuller, Wycliffe Gordon, Urbie Green, Al Grey, Ted Heath, Conrad Herwig, J. J. Johnson, Don Lusher, Albert Mangelsdorff, Glenn Miller, Kid Ory, Frank Rosolino, Frank Rehak,Steve Swell, Jack Teagarden, Bill Watrous, Ron Westray, Kai Winding, and Trummy Young.

Types

The most frequently encountered trombones today are the tenor and bass, though as with other Renaissance instruments such as the recorder, the trombone has been built in every size from piccolo to contrabass.

Technique

As with all brass instruments, progressive tightening of the lips and increased air pressure allow the player to move to a different partial in the harmonic series. In the first or closed position on a B♭ trombone, the notes in the harmonic series begin with the pedal or fundamental B♭1, followed by B♭2 (one octave higher), F3 (a perfect fifth higher), B♭3 (a perfect fourth higher), D4 (a major third higher), F4 (a minor third higher), A♭4 (a minor third higher; this note is always flat and is not usually played in this position, though it has been the practice in Germany and Austria to do so), B♭4 (a major second higher), C5 (a major second higher), D5 (a major second higher), E♭ (a minor second higher, but very sharp), F5 (a major second higher). Very skilled players with a highly- developed facial musculature can go even higher than this, to G5, A♭5, B♭5 and beyond.

In the lower range, significant movement of the slide is required between positions, which becomes more exaggerated on lower pitched trombones, but for higher notes the player need only use the first four positions of the slide since the partials are closer together, allowing higher notes to be played in alternate positions. As an example, F4 (at the bottom of the treble clef) may be played in both first, fourth and sixth positions on a B♭ trombone. The note E1 (or the lowest E on a standard 88-key piano keyboard) is the lowest attainable note on a 9' B♭ tenor trombone, requiring a full 2.24 m of tubing. On trombones without an F attachment, there is a gap between B♭1 (the fundamental in first position) and E2 (the first harmonic in seventh position). Skilled players can produce so-called "falset" notes between these, but the sound is relatively weak and not usually used in performance.

Because of the slide's continuous variation, the trombone is one of the few wind instruments that can produce a true glissando, by moving the slide without interrupting the airflow.

Notation

Unlike most other brass instruments, the trombone is not usually a transposing instrument. Prior to the invention of valve systems, most brasses were limited to playing one overtone series at a time; altering the pitch of the instrument required manually replacing a section of tubing (called a "crook") or picking up an instrument of different length. Their parts were transposed according to which crook or length-of-instrument they used at any given time, so that a particular note on the staff always corresponded to a particular partial on the instrument. Trombones, on the other hand, have used slides since their inception. As such, they have always been fully chromatic, so no such tradition took hold, and trombone parts have always been notated at concert pitch (with one exception, discussed below). Also, it was quite common for trombones to double choir parts; reading in concert pitch meant there was no need for dedicated trombone parts.

Trombone parts are typically notated in bass clef, though sometimes also written in tenor clef or alto clef. The use of alto clef is usually confined to orchestral first trombone parts intended for the alto trombone, with the second (tenor) trombone part written in tenor clef and the third (bass) part in bass clef. As the alto trombone declined in popularity during the 19th century, this practice was gradually abandoned and first trombone parts came to be notated in the tenor or bass clef. Some Russian and Eastern European composers wrote first and second tenor trombone parts on one alto clef staff (the German Robert Schumann was the first to do this). Examples of this practice are evident in scores by Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich. Trombone parts may contain both bass and tenor clef or bass and alto clef sections. The lowest note that a trombone can theoretically play is a low B♭ that is below the staff, in the tuba range

An accomplished performer today is expected to be proficient in reading parts notated in bass clef, tenor clef, alto clef, and (more rarely) treble clef in C, with the British brass band performer expected to handle treble clef in B♭ as well.

Brass bands

In brass band music, the tenor trombone is treated as a transposing instrument in B♭ and reads the treble clef. This puts the notes in exactly the same staff position as they would be if the music were written in a (non-transposing) tenor clef, though the key signature must be adjusted. This is no mere coincidence, for brass bands used to employ a section of alto, tenor and bass trombones in the early to mid-19th century, later replacing the alto with a tenor trombone, all the while notated in the corresponding clefs. Eventually a decision was taken in the early 20th century to replace the tenor clef with the transposing B♭ treble clef in order to aid new starters to integrate more quickly and effectively into the brass band, though the bass trombone, then in G, remained (and is still) notated in concert pitch bass clef. (Company bands used B♭ and E♭ treble clef notation for many instruments in the band to allow players to more easily switch instruments when personnel changed.)

Mutes

See also Brass instrument mutes

A variety of mutes can be used with the trombone to alter its timbre. Many are held in place with the use of cork grips, including the straight, cup, harmon and pixie mutes. Some fit over the bell, like the bucket mute. In addition to this, mutes can be held in front of the bell and moved to cover more or less area for a wah-wah effect. Mutes used in this way include the "hat" (a metal mute shaped like a bowler) and plunger (which looks like, and often is, the rubber suction cup from a sink or toilet plunger).

Variations in construction

Bells

Trombone bells (and sometimes slides) may be constructed of different brass mixtures to achieve slightly different timbres. The most common material is yellow brass, comprising 70% copper and 30% zinc, though other materials used include rose brass (85% copper, 15% zinc) and red brass (90% copper, 10% zinc). These different materials affect the tone quality of the instrument and change the timbre quite considerably. Some manufacturers now offer interchangeable bells so that the player can select which bell he prefers according to the artistic requirements. Tenor trombone bells are usually between 7 and 9 inches in diameter, the most common being sizes from 7½ to 8½ inches. The smallest sizes are found in small jazz trombones and older narrow bore instruments, while the larger sizes are common in orchestral models. Bass trombone bells can be as large as 10½" or more, though are usually either 9½ in or 10 in in diameter. The bell may be constructed out of two separate brass sheets or out of one single piece of metal and hammered on a mandrel until the part is shaped correctly. The edge of the bell may be finished with or without a piece of bell wire to secure it, which also affects the tone quality; most bells are built with bell wire. Occasionally, trombone bells are made from solid sterling silver.

Valve attachments

Valves

Some trombones have valves instead of a slide (see valve trombone). Slide trombone valve attachments may be fitted with rotary valves or sometimes with piston or disc valves, which are modern variations on types of valve invented during the 1820s, but discarded at the time in favor of the rotary valve and the Périnet or piston valve.

Tubing

More often than not, tenor trombones with an F attachment have a larger bore through the attachment than through the straight section (the portion of the trombone through which the air flows when the attachment is not engaged). Typically, for orchestral instruments, the slide bore is 0.547" and the attachment tubing bore is 0.562". A wide variety of valve attachments and combinations are available. Valve attachment tubing usually incorporates a small tuning slide so that the attachment tubing is able to be tuned separately from the rest of the instrument. Most B♭/F tenor and bass trombones include a tuning slide, which is long enough to lower the pitch to E with the valve tubing engaged, enabling the production of B2. Whereas older instruments fitted with valve attachments usually had the tubing coiled rather tightly in the bell section (closed wrap or traditional wrap), modern instruments usually have the tubing kept as free as possible of tight bends in the tubing (open wrap), resulting in a freer response with the valve attachment tubing engaged.

Tuning

Some trombones (principally bass trombones) are tuned through a mechanism in the slide section (Tuning-in-the-Slide or "TIS") rather than via a separate tuning slide in the bell section. This method preserves a smoother expansion from the start of the bell section to the bell flare. The tuning slide in the bell section requires two portions of cylindrical tubing in an otherwise conical part of the instrument, which affects the tone quality.

Slides

Common and popular bore sizes for trombone slides are 0.500", 0.508", 0.525" and 0.547" for tenor trombones, and 0.562" for bass trombones. The slide may also be built with a dual bore configuration, in which the bore of the second leg of the slide is slightly larger than the bore of the first leg, producing a step-wise conical effect. The most common dual bore combinations are 0.481"-0.491", 0.500"-0.508", 0.508"-0.525", 0.525"-0.547", 0.547"-0.562" for tenor trombones, and 0.562"-0.578" for bass trombones.

Mouthpiece

The mouthpiece is a separate part of the trombone and can be interchanged with similarly-sized trombones from different manufacturers. Mouthpiece dimensions vary in length, diameter, rim shape, and cup depth. Each variation affects timbre (tone quality), and is a highly personal decision of advanced trombone players. Typically, a symphonic trombonist will choose a mouthpiece with a deeper cup and sharper inner rim shape in order to produce a rich, full-textured tone quality that is desired in most symphony orchestras. A jazz trombonist, on the other hand, may choose a shallower cup in order to achieve a thinner, less Teutonic tone quality. However, these decisions vary from player to player.

Regional variations

Germany and Austria

German trombones have been built in a wide variety of bore and bell sizes and differ substantially from American designs in many aspects. From the mouthpiece to the bell, there is a great deal of difference in how the traditional German Konzertposaune is constructed. The mouthpiece is typically rather small and is placed into a slide section that uses very long leadpipes of at least 12"-24". The whole instrument is often constructed of gold brass and this naturally characterises the sound, which is usually rather dull compared with British, French or American designs. While bore sizes were considered large in the 19th century, German trombones have altered very little over the last 150 years and are now typically somewhat smaller than their American counterparts. Bell sizes remain very large in all sizes of German trombone and in bass trombones may exceed 10" in diameter. Valve attachments in tenor and bass trombones were traditionally constructed to be engaged via a thumb-operated rotary valve equipped with a leather thong rather than a metal lever. Older models are still to be found with this feature, though modern variants use the metal lever. As with other German and Austrian brass instruments, rotary valves are used to the exclusion of almost all other types of valve, even in valve trombones. Other features often found on German trombones include long water keys and snake decorations on the slide and bell U-bows.

Most trombones actually played in Germany today, especially by amateurs, are in fact built in the American fashion, as those are much more widely available and thus far cheaper.

France

French trombones were built in the very smallest bore sizes up to the end of the Second World War and whilst other sizes were made there, the French usually preferred the tenor trombone to any other size. French music, therefore, usually employed a section of three tenor trombones up to the mid-20th century. Tenor trombones produced in France during the 19th and early 20th centuries featured bore sizes of around 0.450", small bells of not more than 6" in diameter, as well as a funnel-shaped mouthpiece slightly larger than that of the cornet or horn. French tenor trombones were built in both C and B♭, altos in D♭, sopranos in F, piccolos in high B♭, basses in G and E♭, contrabasses in B♭.

Didactics

In recent years, several makers have begun to market compact B♭/C trombones that are especially well suited for young children learning to play the trombone who cannot reach the outer slide positions. Their fundamental note is C, but they have a short valve attachment that puts them in B♭ and is open when the trigger is not depressed. While they have no seventh slide position, C and B natural may be comfortably accessed on the first and second positions by using the trigger. A similar design ("Preacher model") was marketed by C.G. Conn in the 1920s, also under the Wurlitzer label. Currently, B♭/C trombones are available from German makers Günter Frost, Thein and Helmut Voigt as well as the Japanese Yamaha Corporation.

References

- Herbert, Trevor (2006). The Trombone. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10095-7.

- Sadie, Stanley and Tyrrell, John, ed. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-19-517067-9.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Adey, Christopher (1998). Orchestral Performance. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-17724-7.

- Herbert, Trevor and Wallace, John, ed. (1997). The Cambridge Companion to Brass Instruments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56522-7.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Blatter, Alfred (1997). Instrumentation and Orchestration. Belmont: Schirmer. ISBN 0-534-25187-0.

- Wick, Denis (1984). Trombone Technique. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-322378-3.

- Del Mar, Norman (1983). Anatomy of the Orchestra. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-520-05062-2.

- Montagu, Jeremy (1981). The World of Romantic & Modern Musical Instruments. London: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7994-1.

- Baines, Anthony (1980). Brass Instruments: Their History and Development. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-11571-3.

- Montagu, Jeremy (1979). The World of Baroque & Classical Musical Instruments. New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-089-7.

- Bate, Philip (1978). The Trumpet and Trombone. London: Ernest Benn. ISBN 0-510-36413-6.

- Montagu, Jeremy (1976). The World of Medieval & Renaissance Musical Instruments. New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-045-5.

- Gregory, Robin (1973). The Trombone: The Instrument and its Music. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-08816-3.

- Maxted, George (1970). Talking about the Trombone. London: John Baker. ISBN 0-212-98360-1.

- Bluhme, Friedrich, ed. (1962). Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Kassel: Bärenreiter.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Kunitz, Hans (1959). Die Instrumentation: Teil 8 Posaune. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. ISBN 3-7330-0009-9.

- Lavignac, Albert, ed. (1927). Encyclopédie de la musique et Dictionnaire du Conservatoire. Paris: Delagrave.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

See also

External links

- Brass Instruments Information on individual Brass Instruments

- International Trombone Association

- British Trombone Society

- Finnish Trombone and Tuba Association

- Online Trombone Journal

- Brass-Forum.co.uk

- Awesome Trombone Links

- Trombone Page of the World Official Website

- Trombone Italia Magazine - Trombone home page for Italian Trombonist

- Variations on the Trombone

- Tom Izzo, owner of the "only complete set" of trombones in history

- Acoustics of Brass Instruments from Music Acoustics at the University of New South Wales.

- Basstrombone.nl - Your portal to the world of trombone playing

- cdstrombone.com " Discs of trombone"

- Carnyx Scotland " Trombonist John Kenny plays an ancient Celtic war horn"