Narwhal

| Narwhal[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Size comparison with an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Monodon

|

| Species: | M. monoceros

|

| Binomial name | |

| Monodon monoceros Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| |

| Narwhal range (in blue) | |

The Narwhal (Monodon monoceros) is an Arctic species of cetacean. It is a creature rarely found south of latitude 70°N. It is one of two species of white whale in the Monodontidae family (the other is the Beluga whale).

Taxonomy and etymology

The narwhal was one of the many species originally described by Linnaeus in his Systema Naturae.[3] This is based on the Old Norse word nár, meaning "corpse", in reference to the animal's pigmentation. In some parts of the world, the Narwhal is colloquially referred to as the Moon Whale or the Polar Whale. In Inuit language the narwhal is named qilalugaq.[4]

Description

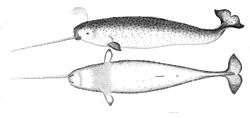

The most conspicuous characteristic of the male narwhal is its single, extraordinarily long tusk. It is an incisor tooth that projects from the left side of the upper jaw and forms a left-handed helix. The tusk can be up to three metres (nearly 10 ft) long (compared with a body length of 4-6 m [13-16 ft]) and weigh up to 10 kg (22 lbs). About one in 500 males has two tusks, which occurs when the right incisor, normally small, also grows out. A female narwhal may also produce a tusk, and there is a single recorded case of a female with dual tusks.[5]

The purpose of the tusk is unknown, though various explanations have been proposed. One explanation suggested that the tusk was used to pierce the ice covering the narwhal's Arctic Sea habitat.[6] Another suggested the tusk was used in echolocation. Other hypothesized uses include courting females, defense, and foraging for food. In yet another theory, the tusk is primarily used for showmanship and for dominance: males with larger tusks are more likely to successfully attract a mate. This hypothesis was suggested by the activity of "tusking," in which two males rub tusks.

However, recent work by a research team suggests that the tusk may in fact be a sensory organ.[7] Electron micrographs of tusks revealed ten million tiny, deep tubules extending from the tusk's surface, apparently connecting to the narwhal's nervous system. [8] While such tubules are present in the teeth of many species, they do not typically extend to the surface of healthy teeth. The exact sensory purpose of the tusk remains unknown, but scientists now hypothesize that it may detect temperature, salinity, pressure, or particulate makeup of the water environment.[7]

Male narwhals weigh up to 1,600 kg (3,500 lb), and the females weigh around 1,000 kg (2,200 lb). Most of the body is pale with brown speckles in color, though the neck, head and edges of the flippers and fluke are nearly black. Older animals are usually more brightly colored than younger animals.[9]

Behavior and diet

Narwhals are quick, active mammals which feed mainly on cod, squid, shrimp and halibut.[10]

In some areas their diet seems to have adapted to include different squids, shrimps, and various fish, such as schooling pelagics, halibuts, and redfishes, which they hunt by spearing with their tusk. Canadian Researcher William Sommers has found that when food is scarce, narwhals will even eat baby seals. Narwhals normally congregate in groups of about five to ten. Sometimes several of these groups might come together, particularly in summer when they congregate on the same coast.

Narwhals prefer to stay near the surface. During a typical deep dive the animal will descend as fast as 2 m/s for eight to ten minutes, reaching a depth of at least 1,500 m (5,000 ft), spend perhaps a couple of minutes at depth before returning to the surface.

Tusking

At times, male narwhals rub one another's tusks together in an activity called "tusking." Because of the tusk's high sensitivity, the males may engage in tusking for its unique sensation.[1]. The tusking may also simply be a way of clearing encrustations from the sensory tubules, analogous to brushing teeth.

Population and distribution

The narwhal is found predominantly in the Atlantic and Russian areas of the Arctic. Individuals are commonly recorded in the northern part of Hudson Bay, Hudson Strait, Baffin Bay; off the east coast of Greenland; and in a strip running east from the northern end of Greenland round to eastern Russia (170° East). Land in this strip includes Svalbard, Franz Joseph Land, and Severnaya Zemlya. The northernmost sightings of narwhal have occurred north of Franz Joseph Land, at about 85° North latitude.

The world population is currently estimated to be around 50,000 individuals.[11] Most estimates of population have concentrated on the fjords and inlets of Northern Canada and western Greenland. Aerial surveys suggest a population of around 20,000 individuals.[citation needed] When submerged animals are also taken into account, the true figure may be in excess of 25,000.

Narwhals are a migratory species. In summer months they move closer to coasts, usually in pods of 10-100. As the winter freeze begins, they move away from shore, and reside in densely-packed ice, surviving in leads and small holes in the ice. As spring comes, these leads open up into channels and the narwhals return to the coastal bays.

Predation and conservation

The main predators of the narwhal are polar bears and orcas. Inuit people are allowed to hunt this whale species legally. The northern climate provides little nutrition in the form of vitamins which can only be obtained through the consumption of seal, whale, and walrus. The livers of these animals are often eaten immediately following the killing by the hunting party in an ancient ceremony of respect for the animal. In Greenland, traditional hunting methods in whaling are used (such as harpooning), but high-speed boats and hunting rifles are frequently used in Northern Canada. PETA and other animal rights groups have long protested the killing of narwhals.[citation needed]

A study published in April, 2008, in the peer-reviewed journal Ecological Applications found the narwhal to be the most potentially vulnerable to climate change when a risk analysis of other Arctic Marine Mammals was conducted. The study quantified the vulnerabilities of 11 year-round Arctic sea mammals.[12]

Cultural references

In Inuit legend, the narwhal was created when a woman holding onto a harpoon had been pulled into the ocean and twisted around the harpoon. The submerged woman was wrapped around a beluga whale on the other end of the harpoon.

Some medieval Europeans believed narwhal tusks to be the horns from the legendary unicorn.[13] As these "horns" were considered to have magic powers, Vikings and other northern traders were able to sell them for many times their weight in gold. The tusks were used to make cups that were thought to negate any poison that may have been slipped into the drink. During the 16th century, Queen Elizabeth received a carved and bejeweled narwhal tusk for £10,000—the cost of a castle (approximately £1.5—2.5 Million in 2007, using the retail price index[14]). The tusks were staples of the cabinet of curiosities.

The truth of the tusk's origin developed gradually during the Age of Exploration, as explorers and naturalists began to visit Arctic regions themselves. In 1555, Olaus Magnus published a drawing of a fish-like creature with a "horn" on its forehead.

References

- ^ Mead, J. G.; Brownell, R. L. Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Template:IUCN2008

- ^ Template:La icon Linnaeus, C (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 824.

- ^ ""narwhal"". Inuktitut Living Dictionary. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- ^ Carwardine, Mark (April 1995). DK Handbooks: Whales Dolphins and Porpoises. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 1564586200.

- ^ Template:"It's Sensitive. Really". William J. Broad, New York Times, 13 December 2005, http://nytimes.com/2005/12/13/science/13narw.html / NYT article RSS link

- ^ a b "Marine Biology Mystery Solved: Function of "Unicorn" Whale's 8-foot Tooth Discovered". Harvard Medical School. 13 December 2005. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2005/12/051214081832.htm

- ^ "Monodon monoceros". Fisheries andAquaculture Department: Species Fact Sheets. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- ^ "The Biology and Ecology of Narwhals". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2008-09-.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Milius, Susan (25 March 2006). "That's One Weird Tooth". Science News. 169 (12). ISSN 0036-8423.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Borenstein, Seth (25 April 2008). "Narwhals more at risk to Arctic warming than polar bears". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Daston, Lorraine and Katharine Park. Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750. New York: Zone Books, 2001.

- ^ Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1264 to 2007

- General references

- "Narwhal". M. P. Heide-Jorgensen (pp 783–787), in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, Perrin, Wursig and Thewissen eds. ISBN 0-12-551340-2

- Narwhal general information

- Narwhal Tooth Expedition and Research Investigation

- Narwhal info

- "Narwhal Found to Have a Trick Up Its Tusk", Scientific American News

External links

- Narwhal Whales Information and images

Galleries

- Paul Nicklen, Canada National Geographic Magazine

- On National Geographic