Center of mass

The center of mass of a system of particles is a specific point at which, for many purposes, the system's mass behaves as if it were concentrated. The center of mass is a function only of the positions and masses of the particles that comprise the system. In the case of a rigid body, the position of its center of mass is fixed in relation to the object (but not necessarily in contact with it). In the case of a loose distribution of masses in free space, such as, say, shot from a shotgun, the position of the center of mass is a point in space among them that may not correspond to the position of any individual mass. In the context of an entirely uniform gravitational field, the center of mass is often erroneously called the center of gravity — the point where gravity can be said to act (although in uniform fields they have the same geomertic location).

The center of mass of a body does not always coincide with its intuitive geometric center, and one can exploit this freedom. Engineers try to design a sports car's center of mass as low as possible to make the car handle better. When high jumpers perform a "Fosbury Flop", they bend their body in such a way that it is possible for the jumper to clear the bar while his or her center of mass does not.[1]

The center of momentum frame is an inertial frame defined as the inertial frame in which the center of mass of a system is at rest. A specific center of momentum frame in which the center of mass is not only at rest, but also at the origin of the coordinate system, is sometimes called the center of mass frame, or center of mass coordinate system.

Definition

The center of mass of a system of particles is defined as the average of their positions, , weighted by their masses, :

For a continuous distribution with mass density and total mass , the sum becomes an integral:

If an object has uniform density then its center of mass is the same as the centroid of its shape.

Examples

- The center of mass of a two-particle system lies on the line connecting the particles (or, more precisely, their individual centers of mass). The center of mass is closer to the more massive object; for details, see barycenter below.

- The center of mass of a ring is at the center of the ring (in the air).

- The center of mass of a solid triangle lies on all three medians and therefore at the centroid, which is also the average of the three vertices.

- The center of mass of a rectangle is at the intersection of the two diagonals.

- In a spherically symmetric body, the center of mass is at the center. This approximately applies to the Earth: the density varies considerably, but it mainly depends on depth and less on the other two coordinates.

- More generally, for any symmetry of a body, its center of mass will be a fixed point of that symmetry.

History

The concept of center of mass was first introduced by the ancient Greek mathematician, physicist, and engineer Archimedes of Syracuse. Archimedes showed that the torque exerted on a lever by weights resting at various points along the lever is the same as what it would be if all of the weights were moved to a single point — their center of mass. In work on floating bodies he demonstrated that the orientation of a floating object is the one that makes its center of mass as low as possible. He developed mathematical techniques for finding the centers of mass of objects of uniform density of various well-defined shapes, in particular a triangle, a hemisphere, and a frustum (of a circular paraboloid).

In the Middle Ages, theories on the center of mass were further developed by Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī, al-Razi (Latinized as Rhazes), Omar Khayyám, and al-Khazini.[2]

Derivation of center of mass

The following equations of motion assume that there is a system of particles governed by internal and external forces. An internal force is a force caused by the interaction of the particles within the system. An external force is a force that originates from outside the system, and acts on one or more particles within the system. The external force need not be due to a uniform field.

For any system with no external forces, the center of mass moves with constant velocity. This applies for all systems with classical internal forces, including magnetic fields, electric fields, chemical reactions, and so on. More formally, this is true for any internal forces that satisfy the weak form of Newton's Third Law.

The total momentum for any system of particles is given by

Where M indicates the total mass, and vcm is the velocity of the center of mass. This velocity can be computed by taking the time derivative of the position of the center of mass.

An analogue to Newton's Second Law is

Where F indicates the sum of all external forces on the system, and acm indicates the acceleration of the center of mass.

Letting the total internal force of the system.

where is the total mass of the system and is a vector yet to be defined, since:

and

then

We therefore have a vectorial definition for center of mass in terms of the total forces in the system. This is particularly useful for two-body systems.

Alternative derivation

Consider first two bodies, with masses m1 and m2, and position vectors r1 and r2. Write M = m1 + m2 for the total mass of the 2-body system, and R for the position vector of the center of mass.

It is reasonable to require, for any system of masses, that the center of mass lie within the convex hull of the system. In particular, for a pair of mass points, this means that the tip of R must lie on the line segment joining the tips of r1 and r2. By geometry, R - r1 = k(r2 - R) for some positive constant k. Taking magnitudes on both sides of this equation, we get d1 = kd2, where d1 is the distance from the center of mass to body 1, and d2 is the distance from the center of mass to body 2. The constant k should obviously depend only on the masses m1 and m2, and we will examine the nature of this dependence.

Assuming the total mass M is nonzero, it is clear that if m2 = 0, the center of mass should coincide with body 1, and d1 = 0. This means d2 = D, the total distance between the two bodies, and m1 = M. Symmetry demands that these relations remain true when the subscripts 1 and 2 are interchanged everywhere.

The simplest model satisfying these requirements is the linear one, d1 = (D/M)m2 and d2 = (D/M)m1.

Under this model, we have k = d1/d2 = m2/m1. Therefore, after multiplying our vector equation by m1, we find that m1(R - r1) = m2(r2 − R), or (m1 + m2)R = m1r1 + m2r2. Thus,

Now suppose there is a third body, of mass m3 and position r3. Temporarily break the symmetry between the three bodies, and define the 3-body center of mass as the 2-body center of mass determined by body 3 together with a single body of mass M0 = m1 + m2 placed at the center of mass of bodies 1 and 2, whose position vector we now denote by R0. The formula derived above gives

Since R turns out to be symmetric in the mi and ri, it would not have mattered had we started by combining bodies 2 and 3, or bodies 1 and 3, instead of bodies 1 and 2. This kind of reasoning clearly extends to any number of masses, and yields the formula

So our simple model of the 2-body center of mass uniquely and consistently determines the corresponding formula in any number of mass points. Writing M = m1 + m2 + ... + mn, the above formula for the center of mass may be expressed in the form

Differentiating both sides yields the principle that

i.e., the sum of the momenta of a number of bodies is the momentum of their center of mass. It is this principle that gives precise expression to the intuitive notion that the system as a whole behaves like a mass of M placed at R, and justifies our simple linear model of the one-dimensional center of mass.

Rotation and centers of mass

The center of mass is often called the center of gravity because any uniform gravitational field g acts on a system as if the mass M of the system were concentrated at the center of mass R. This is seen in at least two ways:

- The gravitational potential energy of a system is equal to the potential energy of a point particle having the same mass M located at R.

- The gravitational torque on a system equals the torque of a force Mg acting at R:

- :

If the gravitational field acting on a body is not uniform, then the center of mass does not necessarily exhibit these convenient properties concerning gravity. As the situation is put in Feynman's influential textbook The Feynman Lectures on Physics:[citation needed]

- "The center of mass is sometimes called the center of gravity, for the reason that, in many cases, gravity may be considered uniform. ...In case the object is so large that the nonparallelism of the gravitational forces is significant, then the center where one must apply the balancing force is not simple to describe, and it departs slightly from the center of mass. That is why one must distinguish between the center of mass and the center of gravity."

Many authors have been less careful, stating that when gravity is not uniform, "the center of gravity" departs from the CM. This usage seems to imply a well-defined "center of gravity" concept for non-uniform fields. Symon, in his textbook Mechanics, shows that the center of gravity of an extended body must always be defined relative to an external point, at which location resides a point mass that is exerting a gravitational force on the object in question. In fact, as Symon says:

- "For two extended bodies, no unique centers of gravity can in general be defined, even relative to each other, except in special cases, as when the bodies are far apart, or when one of them is a sphere....The general problem of determining the gravitational forces between bodies is usually best treated by means of the concepts of the field theory of gravitation..."

Even when considering tidal forces on planets, it is sufficient to use centers of mass to find the overall motion. In practice, for non-uniform fields, one simply does not speak of a "center of gravity".[3]

CM frame

The angular momentum vector for a system is equal to the angular momentum of all the particles around the center of mass, plus the angular momentum of the center of mass, as if it were a single particle of mass :

This is a corollary of the Parallel Axis Theorem.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

Engineering

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

Aeronautical significance

The center of mass is an important point on an aircraft, which significantly affects the stability of the aircraft. To ensure the aircraft is safe to fly, it is critical that the center of mass fall within specified limits. This range varies by aircraft, but as a rule of thumb it is centered about a point one quarter of the way from the wing leading edge to the wing trailing edge (the quarter chord point). If the center of mass is ahead of the forward limit, the aircraft will be less maneuverable, possibly to the point of being unable to rotate for takeoff or flare for landing. If the center of mass is behind the aft limit, the moment arm of the elevator is reduced, which makes it more difficult to recover from a stalled condition. The aircraft will be more maneuverable, but also less stable, and possibly so unstable that it is impossible to fly.

Barycenter in astronomy

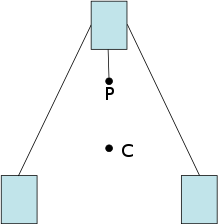

The barycenter (or barycentre; from the Greek βαρύκεντρον) is the point between two objects where they balance each other. For example, it is the center of mass where two or more celestial bodies orbit each other. When a moon orbits a planet, or a planet orbits a star, both bodies are actually orbiting around a point that lies outside the center of the greater body. For example, the moon does not orbit the exact center of the earth, instead orbiting a point outside the Earth's center (but well below the surface of the Earth) where their respective masses balance each other. The barycenter is one of the foci of the elliptical orbit of each body. This is an important concept in the fields of astronomy, astrophysics, and the like (see two-body problem).

In a simple two-body case, r1, the distance from the center of the first body to the barycenter is given by:

where:

- a is the distance between the two bodies' centers;

- m1 and m2 are the masses of the two bodies.

r1 is essentially the semi-major axis of the first body's orbit around the barycenter—and r2 = a − r1 the semi-major axis of the second body's orbit. Where the barycenter is located within the more massive body, that body will appear to "wobble" rather than following a discernible orbit.

The following table sets out some examples from our solar system. Figures are given rounded to three significant figures. The last two columns show R1, the radius of the first (more massive) body, and r1/R1, the ratio of the distance to the barycenter and that radius: a value less than one shows that the barycenter lies inside the first body.

| Larger body |

m1 (mE=1) |

Smaller body |

m2 (mE=1) |

a (km) |

r1 (km) |

R1 (km) |

r1/R1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remarks | |||||||

| Earth | 1 | Moon | 0.0123 | 384,000 | 4,670 | 6,380 | 0.732 |

| The Earth has a perceptible "wobble". | |||||||

| Pluto | 0.0021 | Charon | 0.000254 (0.121 mPluto) |

19,600 | 2,110 | 1,150 | 1.83 |

| Both bodies have distinct orbits around the barycenter, and as such Pluto and Charon were considered as a double planet by many before the redefinition of planet in August 2006. | |||||||

| Sun | 333,000 | Earth | 1 | 150,000,000 (1 AU) |

449 | 696,000 | 0.000646 |

| The Sun's wobble is barely perceptible. | |||||||

| Sun | 333,000 | Jupiter | 318 | 778,000,000 (5.20 AU) |

742,000 | 696,000 | 1.07 |

| The Sun orbits a barycenter just above its surface. | |||||||

If m1 >> m2—which is true for the Sun and any planet—then the ratio r1/R1 approximates to:

Hence, the barycenter of the Sun-planet system will lie outside the Sun only if:

That is, where the planet is heavy and far from the Sun.

If Jupiter had Mercury's orbit (57,900,000 km, 0.387 AU), the Sun-Jupiter barycenter would be only 5,500 km from the center of the Sun (r1/R1 ~ 0.08). But even if the Earth had Eris' orbit (68 AU), the Sun-Earth barycenter would still be within the Sun (just over 30,000 km from the center).

To calculate the actual motion of the Sun, you would need to sum all the influences from all the planets, comets, asteroids, etc. of the solar system (see n-body problem). If all the planets were aligned on the same side of the Sun, the combined center of mass would lie about 500,000 km above the Sun's surface.

The calculations above are based on the mean distance between the bodies and yield the mean value r1. But all celestial orbits are elliptical, and the distance between the bodies varies between the apses, depending on the eccentricity, e. Hence, the position of the barycenter varies too, and it is possible in some systems for the barycenter to be sometimes inside and sometimes outside the more massive body. This occurs where:

Note that the Sun-Jupiter system, with eJupiter = 0.0484, just fails to qualify: 1.05 ≯ 1.07 > 0.954.

Animations

Images are representative, not simulated.

Two bodies of similar mass orbiting around a common barycenter. (similar to the 90 Antiope system) |

Two bodies with a difference in mass orbiting around a common barycenter, as in the Pluto-Charon system. |

Two bodies with a major difference in mass orbiting around a common barycenter (similar to the Earth-Moon system) |

Two bodies with an extreme difference in mass orbiting around a common barycenter (similar to the Sun-Earth system) |

Two bodies with similar mass orbiting around a common barycenter with elliptic orbits (a common situation for binary stars) | |||

Locating the center of mass of an arbitrary 2D physical shape

This method is useful when one wishes to find the centroid of a complex planar shape with unknown dimensions. It relies on finding the center of mass of a thin body of homogenous density having the same shape as the complex planar shape.

|

|

|

| Step 1: An arbitrary 2D shape. | Step 2: Suspend the shape from a location near an edge. Drop a plumb line and mark on the object. | Step 3: Suspend the shape from another location not too close to the first. Drop a plumb line again and mark. The intersection of the two lines is the center of mass. |

Locating center of mass

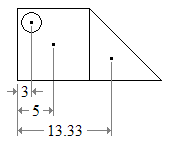

This is a method of determining the center of mass of an L-shaped object.

- Divide the shape into two rectangles, as shown in fig 2. Find the center of masses of these two rectangles by drawing the diagonals. Draw a line joining the center of masses. The center of mass of the shape must lie on this line AB.

- Divide the shape into two other rectangles, as shown in fig 3. Find the center of masses of these two rectangles by drawing the diagonals. Draw a line joining the center of masses. The center of mass of the L-shape must lie on this line CD.

- As the center of mass of the shape must lie along AB and also along CD, it is obvious that it is at the intersection of these two lines, at O. The point O might not lie inside the L-shaped object.

Locating the center of mass of a composite shape

This method is useful when one wishes to find the location of the centroid or center of mass of an object that is easily divided into elementary shapes, whose centers of mass are easy to find (see List of centroids). Here the center of mass will only be found in the x direction. The same procedure may be followed to locate the center of mass in the y direction.

The shape. It is easily divided into a square, triangle, and circle. Note that the circle will have negative area.

The shape. It is easily divided into a square, triangle, and circle. Note that the circle will have negative area.

From the List of centroids, we note the coordinates of the individual centroids.

From the List of centroids, we note the coordinates of the individual centroids.

units.

The center of mass of this figure is at a distance of 8.5 units from the left corner of the figure.

Locating the center of mass by tracing around the perimeter of the shape

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2008) |

A direct development of the planimeter known as an integraph, or integerometer (though a better term is probably moment planimeter), can be used to establish the position of the centroid or center of mass of an irregular shape. This method can be applied to a shape with an irregular, smooth or complex boundary where other methods are too difficult. It was regularly used by ship builders to ensure the ship would not capsize. See Locating the center of mass by mechanical means.

The following elegant proof of how a planimeter works is due largely to O. Henrici and can be found in

O. Henrici, Report on Planimeters, British Assoc. for the Advancement of Science, Report of the 64th meeting, 1894, pp. 496-523.

This paper also contains an interesting history of planimeters up through 1894.

How a planimeter works

Proof of how a planimeter works I like this proof because it is almost entirely geometric, the algebra is minimal, and it can be understood intuitively without calculus. In addition, it shows how both linear and polar planimeters work independently of the linkages in their construction. Consequently, the explanation is valid for variants of these planimeters, which are used in a proof of the isoperimetric inequality. Line Segments Sweeping Out Area The Area Difference Theorem Turning the Moving Segment Into a Planimeter How the Roll of the Wheel is Related to Area Combining the Area Difference Theorem and the Roll of the Wheel Measuring a Region

Line Segments Sweeping Out Area Planimeters work based on the intuitive notion of a moving line segment sweeping out area. Here is a line segment sweeping out a narrow quadrilateral. The segment is oriented by a vector N, which is normal, or perpendicular, to the segment.

The area swept out is signed, or oriented. The positive direction is indicated by N. Area swept out in the direction of N counts positively.

Area swept out in the direction opposite that of N counts negatively.

The Area Difference Theorem Suppose the endpoints of an oriented moving line segment traverse closed curves in the counter clockwise direction. The Moving Segment Theorem says that the signed area swept out by the segment is the difference between the areas enclosed by the curves, that is, A = AR - AL ,

where AR and AL are the areas traversed by the right and left endpoints of the segment, respectively.

The reason for this is very intuitive.

Turning the Moving Segment Into a Planimeter The moving line segment becomes a planimeter by fixing its length and attaching a wheel (red). The axis of the wheel is parallel to the segment. The wheels are clearly seen on the schematics for the polar and linear planimeters, and on the underside of the carriage of my K&E polar planimeter. The surprising fact is that when a polar or linear planimeter is used to trace the boundary of a region, the amount the wheel rolls is proportional to the area of the region. Keep reading to see why. Here is a planimeter moving with its ends following two curves. Even though the curves are different, the length of the planimeter doesn't change. As the planimeter moves, the wheel partially rolls and partially slides. Motion of the segment in the direction of the vector N causes the wheel to roll, which is recorded on a scale attached to the wheel. The motion of the segment along its length causes the wheel to slide, and this motion is not recorded. Thus the wheel records the component of motion in the direction perpendicular to the planimeter's length.

The direction indicated by N is the direction in which area swept out counts positively -- it is not necessarily the direction of motion. In the animation, note that the left end of the planimeter has to move in reverse at one point in order to stay on its curve.

How the Roll of the Wheel is Related to Area There are two basic types of movement of the planimeter.

The first type of motion is when the planimeter moves parallel to itself, sweeping out a parallelogram. The important fact to note is that the roll of the wheel, which records the distance moved perpendicular to the rod, is exactly the height of the parallelogram. If A denotes the signed area swept out and s denotes the roll of the wheel, we get A = ls,

where l is the length of the planimeter and the parallelogram. Note that if the planimeter moves in the direction opposite of N, the wheel rolls backwards. The equation above is still valid, but A and s are both negative.

The second type of motion is when the planimeter rotates about the wheel. In this case part of the area swept out is positive and part of it is negative. Also note that the wheel doesn't roll! In this situation the net area swept out is related to the angle through which the planimeter rotates and the position of the wheel. The formula relating these is A = - 1/2 l l 2 Dq,which takes a little explanation.

The wheel could be located at any point on the rod. The number l is between -1 and 1, and indicates the position of the wheel on the rod. At the right endpoint l = 1; at the left endpoint l = -1; at the midpoint l = 0. In the example shown here l = -3/10.

To get the formula for the signed area swept out, first recall that the area of a circular sector is A = 1/2 r2Dq. If it is clear to you that A should depend linearly on l, note that A = - 1/2 l l2 Dq must be the correct formula since it gives the right signed area for the values l = -1, 0, 1. If this isn't so clear, here is a more complete derivation.

The general motion of the planimeter is a combination of translations and rotations. The signed area swept out is simply the sum of the translational and rotational parts. A = l s - 1/2 l l 2 Dq

Combining the Moving Segment Theorem and the Roll of the Wheel

Now suppose the planimeter rod moves so that it comes to rest in the same position in which it started. Then both formulas above for signed area (boxed in yellow) are valid, and so we get

AR - AL = l s - 1/2 l l 2 Dq .

In addition, Dq is an integer multiple of 2p, generally either 0 or 2p.

Measuring a Region

When a planimeter is used to measure a region, the user moves the right endpoint of the rod, the tracing point, around the boundary of the region to be measured. Consequently the desired area is AR. For a linear planimeter, the left endpoint moves back and forth along a line, enclosing no area, and so AL = 0. Similarly, for a polar planimeter used in the usual way, the left endpoint moves along the arc of a circle, but doesn't go completely around the circle; again AL = 0. For both polar and linear planimeters used in the usual way, the planimeter rod doesn't make a full rotation, and so Dq = 0. Plugging these into the formula above boxed in green yields the simple formula for the area of the region being measured:

AR = l s .

Three simple observations can be made from this.

The area of the region is proportional to the amount the wheel rolls. The constant of proportionality is the length of the planimeter rod. The scale on the wheel takes this into account, allowing the user to simply read the quantity l s from the scale.

It doesn't matter where the wheel is located along the rod.

The left endpoint could follow any path that encloses no area -- polar and linear planimeters are just special cases.

A polar planimeter can be used to measure a large region by placing its pole inside the region. (The pole is the fixed endpoint of the pole arm -- also the center of the circle followed by the left endpoint of the tracer arm.) When used in this way, the left endpoint goes all the way around the circle it follows, and so AL = pr2, where r is the radius of this circle, that is, the length of the pole arm. In addition, the tracer arm makes a full rotation, and so Dq = 2p. Inserting these into the above formula boxed in green yields

AR = l s + pr2 - lp l 2

for the area of the region being measured. The user reads the quantity l s from the scale and then adds pr2 - lp l 2 to get the desired area. The extra quantity added involves the lengths of the two planimeter arms and the location of the wheel. These are constants of the instrument, and are generally printed in the instruction manual.

See also

- Center of percussion

- Center of pressure

- Metacentric height

- Roll center

- Two-body problem

- Weight distribution

Notes

- ^ Van Pelt, Michael (2005). Space Tourism: Adventures in Earth Orbit and Beyond. Springer. p. 185. ISBN 0387402136.

- ^ Salah Zaimeche PhD (2005). Merv, Foundation for Science Technology and Civilization.

- ^ Symon, K. R. (1971). Mechanics, 3rd ed., Reading: Addison-Wesley.[citation needed]

References

- Feynman, Richard (1963). The Feynman Lectures on Physics. Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-02116-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Goldstein, Herbert (2002). Classical Mechanics (3e ed.). Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-65702-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Kleppner, Daniel (1973). An Introduction to Mechanics (2e ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-035048-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Marion, Jerry (1995). Classical Dynamics of Particles and Systems (4e ed.). Harcourt. ISBN 0-03-097302-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Murray, Carl (1999). Solar System Dynamics. Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-57295-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Serway, Raymond A.; Jewett, John W. (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers (6th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-40842-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Symon, Keithe R. (1971). Mechanics (3rd edition ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-07392-7.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Tipler, Paul (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Mechanics, Oscillations and Waves, Thermodynamics (5th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0809-4.

External links

- Centre of mass model - A Background model for segmentation of moving objects in image processing.

- barycenter fold by Paul Niquette.

- Center of Gravity Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Locating the center of mass by mechanical means.

- The dynamic centre of gravity Engineer Xavier Borg - Blaze Labs Research

- Measuring Center of Gravity Space Electronics, manufacturer of center of gravity measurement instruments.

- Motion of the Center of Mass shows that the motion of the center of mass of an object in free fall is the same as the motion of a point object.

- The solar system's barycenter Simulations showing the effect each planet contributes to the solar system's barycenter