Human brain

The human brain is the center of the human nervous system and is a highly complex organ. It has the same general structure as the brains of other mammals, but is over five times as large as the "average brain" of a mammal with the same body size.[citation needed] Most of the expansion comes from the cerebral cortex, a convoluted layer of neural tissue that covers the surface of the forebrain. Especially expanded are the frontal lobes, which are involved in executive functions such as self-control, planning, reasoning, and abstract thought. The portion of the brain devoted to vision is also greatly enlarged in humans.

Brain evolution, from the earliest shrewlike mammals through primates to hominids, is marked by a steady increase in encephalization, or the ratio of brain to body size. The human brain has been estimated to contain 50–100 billion (1011) neurons, of which about 10 billion (1010) are cortical pyramidal cells. These cells pass signals to each other via around 100 trillion (1014) synaptic connections.

In spite of the fact that it is protected by the thick bones of the skull, suspended in cerebrospinal fluid, and isolated from the bloodstream by the blood-brain barrier, the delicate nature of the human brain makes it susceptible to many types of damage and disease. The most common forms of physical damage are closed head injuries such as a blow to the head, a stroke, or poisoning by a wide variety of chemicals that can act as neurotoxins. Infection of the brain is rare because of the barriers that protect it, but is very serious when it occurs. More common are genetically based diseases, such as Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, and many others. A number of psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia and depression, are widely thought to be caused at least partially by brain dysfunctions, although the nature of the brain anomalies is not very well understood.

Structure

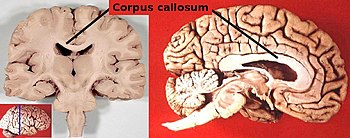

The adult human brain weighs on average about 3 lb (1.5 kg)[1] with a size of around 1130 cubic centimetres (cc) in women and 1260 cc in men, although there is substantial individual variation.[2] The brain is very soft, having a consistency similar to tofu. When alive, it is tan-gray on the outside and mostly yellow-white on the inside, with subtle variations in color. The photo on the right shows a horizontal slice of the head of an adult man, from the National Library of Medicine's Visible Human Project. In this project, two human cadavers (from a man and a woman) were frozen and then sliced into thin sections, which were individually photographed and digitized. The slice here is taken from a small distance below the top of the brain, and shows the cerebral cortex (the convoluted cellular layer on the outside) and the underlying white matter, which consists of myelinated fiber tracts traveling to and from the cerebral cortex.

Situated at the top and covered with a convoluted cortex, the cerebral hemispheres form the largest part of the human brain .[3] Underneath the cerebrum lies the brainstem, resembling a stalk on which the cerebrum is attached. At the rear of the brain, beneath the cerebrum and behind the brainstem, is the cerebellum, a structure with a horizontally furrowed surface that makes it look different from any other brain area. The same structures are present in other mammals, although the cerebellum is not so large relative to the rest of brain. As a rule, the smaller the cerebrum, the less convoluted the cortex. The cortex of a rat or mouse is almost completely smooth. The cortex of a dolphin or whale, on the other hand, is more convoluted than the cortex of a human.

The dominant feature of the human brain is corticalization. The cerebral cortex in humans is so large that it overshadows every other part of the brain. A few subcortical structures show alterations reflecting this trend. The cerebellum, for example, has a medial zone connected mainly to subcortical motor areas, and a lateral zone connected primarily to the cortex. In humans the lateral zone takes up a much larger fraction of the cerebellum than in most other mammalian species. Corticalization is reflected in function as well as structure. In a rat, surgical removal of the entire cerebral cortex leaves an animal that is still capable of walking around and interacting with the environment. In a human, comparable damage produces a permanent state of coma.

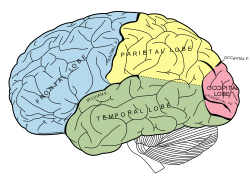

The cerebral cortex is nearly symmetric in outward form, with left and right hemispheres. Anatomists conventionally divide each hemisphere into four "lobes", the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, and occipital lobe. It is important to realize that this categorization does not actually arise from the structure of the cortex itself: the lobes are named after the bones of the skull that overlie them. There is one exception: the border between the frontal and parietal lobes is shifted backward to the central sulcus, a deep fold that marks the line where primary somatosensory cortex and primary motor cortex come together.

The cerebral cortex is essentially a two-dimensional sheet of neural tissue, folded in a way that allows a large surface area to fit within the confines of the skull. Each cerebral hemisphere, in fact, has a total surface area of about 1.3 square feet.[4] Anatomists call each cortical fold a sulcus, and the smooth area between folds a gyrus. Most human brains show a similar pattern of folding, but there are enough variations in the shape and placement of folds to make every brain unique. Nevertheless, the pattern is consistent enough for each major fold to have a name, such as "superior frontal gyrus", "postcentral sulcus", "trans-occipital sulcus", etc.

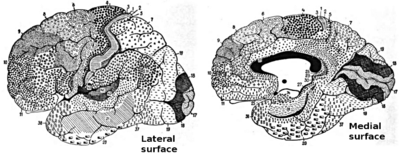

Different parts of the cerebral cortex are involved in different cognitive and behavioral functions. The differences show up in a number of ways: the effects of localized brain damage, regional activity patterns when the brain is examined using functional imaging techniques, connectivity with subcortical areas, and regional differences in the cellular architecture of the cortex. Anatomists describe most of the cortex—the part they call isocortex—as having six layers, but not all layers are apparent in all areas, and even when a layer is present, its thickness and cellular organization can vary. Several anatomists have constructed maps of cortical areas on the basis of variations in the appearance of the layers as seen with a microscope. One of the most widely used schemes came from Brodmann, who assigned numbers from 1 to 52 to brain areas (later anatomists have subdivided many of them). Thus, as a few random examples, Brodmann area 1 is the primary somatosensory cortex; Brodmann area 17 is the primary visual cortex; Brodmann area 25 is the anterior cingulate cortex; etc.

Topography

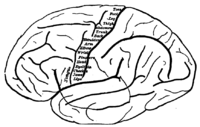

Many of these brain areas themselves have complex internal structures. In a number of cases, brain areas are organized into "topographic maps", where adjoining bits of the cortex represent adjoining parts of the body, or of some more abstract entity. One of the simplest examples is the primary motor cortex, a strip of tissue running along the anterior edge of the central sulcus, as shown in the image to the right. Motor areas innervating each part of the body arise from a distinct zone, with neighboring body parts represented by neighboring zones. Electrical stimulation of the cortex at any point causes a muscle-contraction in the represented body part. This "somatotopic" representation is not evenly distributed, however. The head, for example, is represented by a region about three times as large as the zone for the entire back and trunk. The level of detail determines the precision of motor control and sensory discrimination. The areas for the lips, fingers, and tongue are particularly expanded in proportion to the sizes of the body parts they represent.

In visual areas, the maps are retinotopic—that is, they reflect the topography of the retina, the layer of light-activated neurons lining the back of the eye. In this case too the representation is uneven: the fovea—the area at the center of the visual field—is greatly overrepresented compared to the periphery. The visual circuitry in the human cerebral cortex contains several dozen distinct retinotopic maps, each devoted to analyzing the visual input stream in a particular way. The primary visual cortex (Brodmann area 17), which is the main recipient of direct input from the visual part of the thalamus, contains many neurons that are most easily activated by edges with a particular orientation moving across a particular point in the visual field. Visual areas farther downstream extract features such as color, motion, and shape.

In auditory areas, the primary map is tonotopic. Sounds are parsed according to frequency (i.e., high pitch vs low pitch) by subcortical auditory areas, and this parsing is reflected by the primary auditory zone of the cortex. As with the visual system, there are a number of tonotopic cortical maps, each devoted to analyzing sound in a particular way.

Within a topographic map there can sometimes be finer levels of spatial structure. In the primary visual cortex, for example, where the main organization is retinotopic and the main responses are to moving edges, cells that respond to different edge-orientations are spatially segregated.

Lateralization

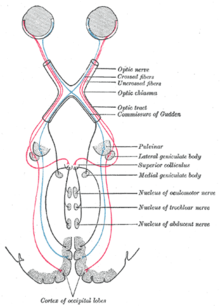

Each hemisphere of the brain interacts mainly with one half of the body, but for reasons that are unclear, the connections are crossed: the left side of the brain interacts with the right side of the body, and vice versa. Motor connections from the brain to the spinal cord, and sensory connections from the spinal cord to the brain, both cross the midline at brainstem levels. Visual input follows a more complex rule: the optic nerves from the two eyes come together at a point called the optic chiasm, and half of the fibers from each nerve split off to join the other. The result is that connections from the left half of the retina, in both eyes, go to the left side of the brain, whereas connections from the right half of the retina go to the right side of the brain. Because each half of the retina receives light coming from the opposite half of the visual field, the functional consequence is that visual input from the left side of the world goes to the right side of the brain, and vice versa. Thus, the right side of the brain receives somatosensory input from the left side of the body, and visual input from the left side of the visual field—an arrangement that presumably is helpful for visuomotor coordination.

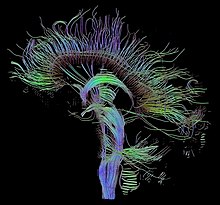

The two cerebral hemispheres are connected by a very large nerve bundle called the corpus callosum, which crosses the midline above the level of the thalamus. There are also two much smaller connections, the anterior commisure and hippocampal commisure, as well as many subcortical connections that cross the midline. The corpus callosum is the main avenue of communication between the two hemispheres, though. It connects each point on the cortex to the mirror-image point in the opposite hemisphere, and also connects to functionally related points in different cortical areas.

In most respects, the left and right sides of the brain are symmetrical in terms of function. For example, the counterpart of the left-hemisphere motor area controlling the right hand is the right-hemisphere area controlling the left hand. There are, however, several very important exceptions, involving language and spatial cognition. In most people, the left hemisphere is "dominant" for language: a stroke that damages a key language area in the left hemisphere can leave the victim unable to speak or understand, whereas equivalent damage to the right hemisphere would cause only minor impairment to language skills.

A substantial part of our current understanding of the interactions between the two hemispheres has come from the study of "split-brain patients"—people who underwent surgical transection of the corpus callosum in an attempt to reduce the severity of epileptic seizures. These patients do not show unusual behavior that is immediately obvious, but in some cases can behave almost like two different people in the same body, with the right hand taking an action and then the left hand undoing it. Most such patients, when briefly shown a picture on the right side of the point of visual fixation, are able to describe it verbally, but when the picture is shown on the left, are unable to describe it, but may be able to give an indication with the left hand of the nature of the object shown.

It should be noted that the differences between left and right hemispheres are greatly overblown in much of the popular literature on this topic. The existence of differences has been solidly established, but many popular books go far beyond the evidence in attributing features of personality or intelligence to the left or right hemisphere dominance.

Sources of information

Information about the structure and function of the human brain comes from a variety of sources. Most information about the cellular components of the brain and how they work comes from studies of animal subjects, using techniques described in the brain article. Some techniques, however, are used mainly in humans, and therefore are described here.

EEG

By placing electrodes on the scalp it is possible to record the summed electrical activity of the cortex, in a technique known as electroencephalography (EEG).[5] EEG measures mass changes in population synaptic activity from the cerebral cortex, but can only detect changes over large areas of the brain, with very little sensitivity for sub-cortical activity. EEG recordings can detect events lasting only a few thousandths of a second, so they have good temporal resolution, but the tradeoff is that they have very poor spatial resolution.

MEG

Apart from measuring the electric field around the skull it is possible to measure the magnetic field directly in a technique known as magnetoencephalography (MEG).[6] This technique has the same temporal resolution as EEG but much better spatial resolution, although not as good as fMRI. The greatest disadvantage of MEG is that, because the magnetic fields generated by neural activity are very weak, the method is only capable of picking up signals from near the surface of the cortex, and even then, only neurons located in the depths of cortical folds (sulci) have dendrites oriented in a way that gives rise to detectable magnetic fields outside the skull.

Structural and functional imaging

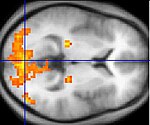

There are several methods for detecting brain activity changes by three-dimensional imaging of local changes in blood flow. The older methods are SPECT and PET, which depend on injection of radioactive tracers into the bloodstream. The newest method, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), has considerably better spatial resolution and involves no radioactivity.[7] Using the most powerful magnets currently available, fMRI can localize brain activity changes to regions as small as one cubic millimeter. The downside is that the temporal resolution is poor: when brain activity increases, the blood flow response is delayed by 1–5 seconds and lasts for at least 10 seconds. Thus, fMRI is a very useful tool for learning which brain regions are involved in a given behavior, but gives little information about the temporal dynamics of their responses. A major advantage for fMRI is that, because it is non-invasive, it can readily be used on human subjects.

Effects of brain damage

A key source of information about the function of brain regions is the effects of damage to them.[8] In humans, strokes have long provided a "natural laboratory" for studying the effects of brain damage. Most strokes result from a blood clot lodging in the brain and blocking the local blood supply, causing damage or destruction of nearby brain tissue: the range of possible blockages is very wide, leading to a great diversity of stroke symptoms. Analysis of strokes is limited by the fact that damage often crosses into multiple regions of the brain, not along clear-cut borders, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions.

Language

In human beings, it is the left hemisphere that usually contains the specialized language areas. While this holds true for 97% of right-handed people, about 19% of left-handed people have their language areas in the right hemisphere and as many as 68% of them have some language abilities in both the left and the right hemisphere. The two hemispheres are thought to contribute to the processing and understanding of language: the left hemisphere processes the linguistic meaning of prosody, while the right hemisphere processes the emotions conveyed by prosody.[9] Studies of children have shown that if a child has damage to the left hemisphere, the child may develop language in the right hemisphere instead. The younger the child, the better the recovery. So, although the "natural" tendency is for language to develop on the left, human brains are capable of adapting to difficult circumstances, if the damage occurs early enough.

The first language area within the left hemisphere to be discovered is called Broca's Area, after Paul Broca. The Broca's area doesn't just handle getting language out in a motor sense, though. It seems to be more generally involved in the ability to deal with grammar itself, at least the more complex aspects of grammar. For example, it handles distinguishing a sentence in passive form from a simpler subject-verb-object sentence. For instance, the sentence: "The boy was hit by the girl." implies the girl hit the boy, not the other way around. As a simple subject-verb-object interpretation it could mean: "The boy was hit by the girl.", and therefore, the boy hit the girl.

The second language area to be discovered is called Wernicke's Area, after Carl Wernicke, a German neurologist. The problem of not understanding the speech of others is known as Wernicke’s Aphasia. Wernicke's is not just about speech comprehension. People with Wernicke's Aphasia also have difficulty naming things, often responding with words that sound similar, or the names of related things, as if they are having a very hard time with their mental "dictionaries."

Pathology

Clinically, death is defined as an absence of brain activity as measured by EEG. Injuries to the brain tend to affect large areas of the organ, sometimes causing major deficits in intelligence, memory, and movement. Head trauma caused, for example, by vehicle or industrial accidents, is a leading cause of death in youth and middle age. In many cases, more damage is caused by resultant edema than by the impact itself. Stroke, caused by the blockage or rupturing of blood vessels in the brain, is another major cause of death from brain damage.

Other problems in the brain can be more accurately classified as diseases rather than injuries. Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, motor neurone disease, and Huntington's disease are caused by the gradual death of individual neurons, leading to decrements in movement control, memory, and cognition.

Mental disorders, such as clinical depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder may involve particular patterns of neuropsychological functioning related to various aspects of mental and somatic function. These disorders may be treated by psychotherapy, psychiatric medication or social intervention and personal recovery work; the underlying issues and associated prognosis vary significantly between individuals.

Some infectious diseases affecting the brain are caused by viruses and bacteria. Infection of the meninges, the membrane that covers the brain, can lead to meningitis. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (also known as mad cow disease), is deadly in cattle and humans and is linked to prions. Kuru is a similar prion-borne degenerative brain disease affecting humans. Both are linked to the ingestion of neural tissue, and may explain the tendency in some species to avoid cannibalism. Viral or bacterial causes have been reported in multiple sclerosis and Parkinson's disease, and are established causes of encephalopathy, and encephalomyelitis.

Many brain disorders are congenital. Tay-Sachs disease, Fragile X syndrome, and Down syndrome are all linked to genetic and chromosomal errors. Many other syndromes, such as the intrinsic circadian rhythm disorders, are suspected to be congenital as well. Development of the brain can be caused by genetic factors, drug use, nutritional deficiencies, and infectious diseases during pregnancy.

Certain brain disorders are treated by brain neurosurgeons while others are treated by neurologists and psychiatrists.

Notes

- ^ Carpenter's Human Neuroanatomy, Ch. 1

- ^ Cosgrove et al, 2007

- ^ Principles of Neural Science, p 324

- ^ Toro et al, 2008

- ^ Fisch and Spehlmann's EEG primer

- ^ Preissl, Magnetoencephalography

- ^ Buxton, Introduction to Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- ^ Andrews, Neuropsychology

- ^ Manlove, George (2005). "Deleted Words". UMaine Today Magazine. Retrieved 2007-02-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

References

- Andrews, DG (2001). Neuropsychology. Psychology Press. ISBN 9781841691039.

- Buxton, RB (2002). An Introduction to Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Principles and Techniques. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521581134.

- Cosgrove, KP (2007). "Evolving knowledge of sex differences in brain structure, function, and chemistry". Biol Psychiat. 62: 847–55. PMID 17544382.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Fisch, BJ (1999). Fisch and Spehlmann's EEG Primer: Basic Principles of Digital and Analog EEG. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780444821485.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Kandel, ER (2000). Principles of Neural Science. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 9780838577011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Parent, A (1995). Carpenter's Human Neuroanatomy. Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780683067521.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Preissl, H (2005). Magnetoencephalography. Academic Press. ISBN 9780123668691.

- Toro, R (2008). "Brain size and folding of the human cerebral cortex". 18: 2352–7. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhm261. PMID 18267953.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Simon, Seymour (1999). The Brain. HarperTrophy. ISBN 0-688-17060-9

- Thompson, Richard F. (2000). The Brain: An Introduction to Neuroscience. Worth Publishers. ISBN 0-7167-3226-2

- Campbell, Neil A. and Jane B. Reece. (2005). Biology. Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-8053-7171-0

See also

- Cephalic disorders, concerning defects of the head, especially the brain

- Cerebral hemispheres

- History of the brain

- Lateralization of brain function

- Lobes of the brain

- Neuroanatomy

- Neuroanthropology

- Neuroscience

- Regions in the human brain

- Common misconceptions about the brain

External links

- The Brain from Top to Bottom

- The Whole Brain Atlas

- High-Resolution Cytoarchitectural Primate Brain Atlases

- Brain Facts and Figures

- Current Research Regarding the Human Brain ScienceDaily

- Estimating the computational capabilities of the human brain

- When will computer hardware match the human brain? – an article by Hans Moravec

- How the human brain works

- Everything you wanted to know about the human brain — Provided by New Scientist.

- Differences between female & male human brains

- Surface Anatomy of the Brain

- Scientific American Magazine (May 2005 Issue) His Brain, Her Brain About differences between female and male brains.