Jerry Fodor

Jerry Alan Fodor | |

|---|---|

| Era | 20th / 21st-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | Analytic |

Main interests | Philosophy of mind Philosophy of language Cognitive science Rationalism · Cognitivism Functionalism |

Notable ideas | Modularity of mind Language of thought |

Jerry Alan Fodor (born 1935 in New York City, New York) is an American philosopher and cognitive scientist. He is the State of New Jersey Professor of Philosophy at Rutgers University and is also the author of many works in the fields of philosophy of mind and cognitive science, in which he has laid the groundwork for the modularity of mind and the language of thought hypotheses, among other ideas. Fodor is of Jewish descent.

Fodor argues that mental states, such as beliefs and desires, are relations between individuals and mental representations. He maintains that these representations can only be correctly explained in terms of a language of thought (LOT) in the mind. Further, this language of thought itself is an actually existing thing that is codified in the brain and not just a useful explanatory tool. Fodor adheres to a species of functionalism, maintaining that thinking and other mental processes consist primarily of computations operating on the syntax of the representations that make up the language of thought.

For Fodor, significant parts of the mind, such as perceptual and linguistic processes, are structured in terms of modules, or "organs", which are defined by their causal and functional roles. These modules are relatively independent of each other and of the "central processing" part of the mind, which has a more global and less "domain specific" character. Fodor suggests that the character of these modules permits the possibility of causal relations with external objects. This, in turn, makes it possible for mental states to have contents that are about things in the world. The central processing part, on the other hand, takes care of the logical relations between the various contents and inputs and outputs.

Although Fodor originally rejected the idea that mental states must have a causal, externally determined aspect, he has in recent years devoted much of his writing and study to the philosophy of language because of this problem of the meaning and reference of mental contents. His contributions in this area include the so-called asymmetric causal theory of reference and his many arguments against semantic holism. Fodor strongly opposes reductive accounts of the mind. He argues that mental states are multiply realizable and that there is a hierarchy of explanatory levels in science such that the generalizations and laws of a higher-level theory of psychology or linguistics, for example, cannot be captured by the low-level explanations of the behavior of neurons and synapses.

Biography

Jerry Fodor was born in New York City in 1935. He received his A.B. degree (summa cum laude) from Columbia University in 1956, where he studied with Sydney Morgenbesser, and a PhD in Philosophy from Princeton University in 1960, under the direction of Hilary Putnam. From 1959-86, Fodor was on the faculty of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts. From 1986–88, he was a full professor at the City University of New York (CUNY). Since 1988 he has been State of New Jersey Professor of Philosophy and Cognitive Science at Rutgers University in New Jersey.[1] Besides his interest in philosophy, Fodor is a passionate follower of opera and regularly writes popular columns for the London Review of Books on the subject.

One of Fodor's most notable former colleagues at Rutgers, the New Mysterian philosopher Colin McGinn, has described Fodor in these words:

"(Fodor) is a gentle man inside a burly body, and prone to an even burlier style of arguing. He is shy and voluble at the same time ... a formidable polemicist burdened with a sensitive soul.... Disagreeing with Jerry on a philosophical issue, especially one dear to his heart can be a chastening experience.... His quickness of mind, inventiveness, and sharp wit are not to be tangled with before your first cup of coffee in the morning. Adding Jerry Fodor to the faculty at Rutgers [University] instantly put it on the map, Fodor being by common consent the leading philosopher of mind in the world today. I had met him in England in the seventies and ... found him to be the genuine article, intellectually speaking (though we do not always see eye to eye)."[2]

Fodor is a member of the honorary societies Phi Beta Kappa and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He has received numerous awards and honors: New York State Regent's Fellow, Woodrow Wilson Fellow (Princeton University), Chancellor Greene Fellow (Princeton University), Fulbright Fellow (Oxford University), Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, and Guggenheim Fellow.[3]

He lives in New York with his wife, Janet Dean Fodor. He has two grown children.

Fodor and the nature of mental states

In his book Propositional Attitudes (1978), Fodor introduced the key idea that mental states are relations between individuals and mental representations. Despite the changes in many of his positions over the years, the idea that intentional attitudes are relational has remained unchanged from its original formulation up to the present time.[4]

In that book, he attempted to show how mental representations, specifically sentences in the language of thought, are necessary to explain this relational nature of mental states. Fodor considers two alternative hypotheses. The first completely denies the relational character of mental states and the second considers mental states to be two-place relations. The latter position can be further subdivided into the Carnapian view that such relations are between individuals and sentences of natural languages[5][6][7] and the Fregean view that they are between individuals and the propositions expressed by such sentences.[8] Fodor's own position, instead, is that to properly account for the nature of intentional attitudes, it is necessary to employ a three-place relation between individuals, representations and propositional contents.[4]

Considering mental states to be three-place relations in this way, representative realism makes it possible to hold together all of the elements necessary to the solution of this problem. Further, mental representations are not only the objects of beliefs and desires, but are also the domain over which mental processes operate. They can be considered the ideal link between the syntactic notion of mental content and the computational notion of functional architecture. These notions are, according to Fodor, our best explanation of mental processes.[4]

The functional architecture of the mind

Following in the path plowed by linguist Noam Chomsky, Fodor developed a strong commitment to the idea of psychological nativism.[9] Nativism is the belief in the innateness of many cognitive functions and concepts. For Fodor, this position emerges naturally out of his criticism of behaviourism and associationism. These criticisms also led him to the formulation of his well-known hypothesis of the modularity of the mind.

Historically, questions about mental architecture have been divided into two contrasting theories about the nature of the faculties. The first can be described as a "horizontal" view because it sees mental processes as interactions between faculties which are not domain specific. For example, a judgment remains a judgment whether it is judgment about a perceptual experience or a judgment about the understanding of language. The second can be described as a "vertical" view because it claims that our mental faculties are domain specific, genetically determined, associated with distinct neurological structures, and so on.[9]

The vertical vision can be traced back to the 19th century movement called phrenology and its founder Franz Joseph Gall. Gall claimed that mental faculties could be associated with specific physical areas of the brain. Hence, someone's level of intelligence, for example, could be literally "read off" from the size of a particular bump on his posterior parietal lobe.[10] This simplistic view of modularity has been disproved over the course of the last century.

Fodor revived the idea of modularity, without the notion of precise physical localizability, in the 1980s, and became one of the most vocal proponents of it with the 1983 publication of his monograph Modularity of Mind.[10] Two properties of modularity in particular, informational encapsulation and domain specificity, make it possible to tie together questions of functional architecture with those of mental content. The ability to elaborate information independently from the background beliefs of individuals that these two properties allow permits Fodor to give an atomistic and causal account of the notion of mental content. The main idea, in other words, is that the properties of the contents of mental states can depend, rather than exclusively on the internal relations of the system of which they are a part, also on their causal relations with the external world.[10]

Fodor's notions of mental modularity, informational encapsulation and domain specificity have been taken up and expanded, much to his own chagrin, by cognitive scientists such as Zenon Pylyshyn and evolutionary psychologists such as Steven Pinker and Henry Plotkin, among many others.[11][12][13] But Fodor complains that Pinker, Plotkin and other members of what he sarcastically calls "the New Synthesis" have taken modularity and similar ideas way too far. He insists that the mind is not "massively modular" and that, contrary to what these researchers would have us believe, the mind is still a very long way from having been explained by the computational, or any other, model.[14]

Intentional realism

In A Theory of Content and Other Essays (1990), Fodor takes up another of his central notions: the question of the reality of mental representations.[15] Fodor needs to justify representational realism to justify the idea that the contents of mental states are expressed in symbolic structures such as those of the LOT.

Fodor's criticism of Dennett

Fodor starts with some criticisms of so-called standard realism. This view is characterized, according to Fodor, by two distinct assertions. One of these regards the internal structure of mental states and asserts that such states are non-relational. The other concerns the semantic theory of mental content and asserts that there is an isomorphism between the causal roles of such contents and the inferential web of beliefs. Among modern philosophers of mind, the majority view seems to be that the first of these two assertions is false, but that the second is true. Fodor departs from this view in accepting the truth of the first thesis but rejecting strongly the truth of the second.[15]

In particular, Fodor criticizes the instrumentalism of Daniel Dennett.[15] Dennett maintains that it is possible to be realist with regard to intentional states without having to commit oneself to the reality of mental representations.[16] Now, according to Fodor, if one remains at this level of analysis, then there is no possibility of explaining why the intentional strategy works:

- "There is...a standard objection to instrumentalism...: it is difficult to explain why the psychology of beliefs/desires works so well, if the psychology of beliefs/desires is, in fact, false....As Putnam, Boyd and others have emphasized, from the predictive successes of a theory to the truth of that theory there is surely a presumed inference; and this is even more likely when... we are dealing with the only theory in play which is predictively crowned with success. It is not obvious...why such a presumption should not militate in favour of a realist conception...of the interpretations of beliefs/desires."[17]

Productivity, compositionality and thought

Fodor also has positive arguments in favour of the reality of mental representations in terms of the LOT. He maintains that if language is the expression of thoughts and language is systematic, then thoughts must also be systematic. Systematicity in natural languages tends to be explained in terms of two more basic concepts: productivity and compositionality. The fact that systematicity and productivity depend on the compositional structure of language means that language has a combinatorial semantics. If thought also has such a combinatorial semantics, then there must be a language of thought.[18]

The second argument that Fodor provides in favour of representational realism involves the processes of thought. This argument touches on the relation between the representational theory of mind and models of its architecture. If the sentences of Mentalese require unique processes of elaboration then they require a computational mechanism of a certain type. The syntactic notion of mental representations goes hand in hand with the idea that mental processes are calculations which act only on the form of the symbols which they elaborate. And this is the computational theory of the mind. Consequently, the defence of a model of architecture based on classic artificial intelligence passes inevitably through a defence of the reality of mental representations.[18]

For Fodor, this formal notion of thought processes also has the advantage of highlighting the parallels between the causal role of symbols and the contents which they express. In his view, syntax is what plays the role of mediation between the causal role of the symbols and their contents. The semantic relations between symbols can be "imitated" by their syntactic relations. The inferential relations which connect the contents of two symbols can be imitated by the formal syntax rules which regulate the derivation of one symbol from another.[18]

The nature of content

From the beginning of the 1980s, Fodor has adhered to a causal notion of mental content and of meaning. This idea of content contrasts sharply with the inferential role semantics to which Fodor subscribed earlier in his career. Fodor now criticizes inferential role semantics (IRS) because its commitment to an extreme form of holism excludes the possibility of a true naturalization of the mental. But naturalization must include an explanation of content in atomistic and causal terms.[19]

Anti-holism

Fodor’s criticisms of holism are many and various. He identifies the central problem with all the different notions of holism as the idea that the determining factor in semantic evaluation is the notion of an "epistemic bond". Briefly, P is an epistemic bond of Q if the meaning of P is considered by someone to be relevant for the determination of the meaning of Q. Meaning holism strongly depends on this notion. The identity of the content of a mental state, under holism, can only be determined by the totality of its epistemic bonds . And this makes the realism of mental states an impossibility:

- "If people differ in an absolutely general way in their estimations of epistemic relevance, and if we follow the holism of meaning and individuate intentional states by way of the totality of their epistemic bonds, the consequence will be that two people (or, for that matter, two temporal sections of the same person) will never be in the same intentional state. Therefore, two people can never be subsumed under the same intentional generalizations. And, therefore, intentional generalization can never be successful. And, therefore again, there is no hope for an intentional psychology."[19]

The asymmetric causal theory

Having criticized the idea that semantic evaluation concerns only the internal relations between the units of a symbolic system, the way is open for Fodor to adopt an externalist position with respect to mental content and meaning. For Fodor, in recent years, the problem of naturalization of the mental is tied to the possibility of giving "the sufficient conditions for which a piece of the world is relative to (expresses, represents, is true of) another piece" in non-intentional and non-semantic terms. If this goal is to be achieved within a representational theory of the mind, then the challenge is to devise a causal theory which can establish the interpretation of the primitive non-logical symbols of the LOT. Fodor’s initial proposal is that what determines that the symbol for “water” in Mentalese expresses the property H2O is that the occurrences of that symbol are in certain causal relations with water. The intuitive version of this causal theory is what Fodor calls the "Crude Causal Theory." According to this theory, the occurrences of symbols express the properties which are the causes of their occurrence. The term “horse”, for example, says of a horse that it is a horse. In order to do this, it is necessary and sufficient that certain properties of an occurrence of the symbol "horse" be in a law-like relation with certain properties which determine that something is an occurrence of horse.[15]

The main problem with this theory is that of erroneous representations. There are two unavoidable problems with the idea that "a symbol expresses a property if it is.. necessary that all and only the presences of such a property cause the occurrences." The first is that not all horses cause occurrences of horse. The second is that not only horses cause occurrences of horse. Sometimes the A(horses) are caused by A (horses), but at other times---when, for example, because of the distance or conditions of low visibility, one has confused a cow for a horse—the A (horses) are caused by B (cows). In this case the symbol A doesn’t express just the property A, but the disjunction of properties A or B. The crude causal theory is therefore incapable of distinguishing the case in which the content of a symbol is disjunctive from the case in which it isn’t. This gives rise to what Fodor calls the "problem of disjunction."

Fodor responds to this problem with what he defines as a "a slightly less crude causal theory." According to this approach, it is necessary to break the symmetry at the base of the crude causal theory. Fodor must find some criterion for distinguishing the occurrences of A caused by As (true) from those caused by Bs (false). The point of departure, according to Fodor, is that while the false cases are ontologically dependent on the true cases, the reverse is not true. There is an asymmetry of dependence , in other words, between the true contents (A= A) and the false ones (A = A or B). The first can subsist independently of the second, but the second can occur only because of the existence of the first:

- From the point of view of semantics, errors must be accidents: if in the extension of "horse" there are no cows, then it cannot be required for the meaning of "horse" that cows be called horses. On the other hand, if "horse" did not mean that which it means, and if it were an error for horses, it would never be possible for a cow to be called "horse." Putting the two things together, it can be seen that the possibility of falsely saying "this is a horse" presupposes the existence of a semantic basis for saying it truly, but not vice versa. If we put this in terms of the crude causal theory, the fact that cows cause one to say "horse" depends on the fact that horses cause one to say "horse"; but the fact that horses cause one to say "horse" does not depend on the fact that cows cause one to say "horse"..."[15]

Functionalism

During the 1960s, various philosophers such as Donald Davidson, Hilary Putnam, and Fodor tried to resolve the puzzle of developing a way to preserve the explanatory efficacy of mental causation and so-called "folk psychology" while adhering to a materialist vision of the world which did not violate the "generality of physics." Their proposal was, first of all, to reject the then-dominant theories in philosophy of mind: behaviorism and the type identity theory.[20] The problem with logical behaviorism was that it failed to account for causation between mental states and such causation seems to be essential to psychological explanation, especially if one considers that behavior is not an effect of a single mental event/cause but is rather the effect of a chain of mental events/causes. The type-identity theory, on the other hand, failed to explain the fact that radically different physical systems can find themselves in the same identical mental state. Besides being deeply anthropocentric (why should humans be the only thinking organisms in the universe?), the type-type theory also failed to deal with accumulating evidence in the neurosciences that every single human brain is different from all the others. Hence, the impossibility of referring to common mental states in different physical systems manifests itself not only between different species but also between organisms of the same species.

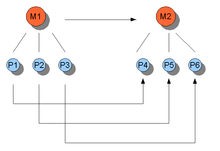

The solution to these problems, according to Fodor, is to be found in functionalism, a hypothesis which was designed to overcome the failings of both dualism and reductionism. Without going into detail here, the idea is that what is important is the function of a mental state regardless of the physical substrate which implements it. The foundation for this view lies in the principle of the multiple realizability of the mental. Under this view, for example, I and a computer can both instantiate ("realize") the same functional state though we are made of completely different material stuff (see graphic at right). On this basis functionalism can be classified as a form of token materialism.[21]

Criticism

Many of Fodor's ideas have been challenged by a wide variety of philosophers of diverse orientation. For example, the language of thought hypothesis has been accused of either falling prey to an infinite regress or of being superfluous. Specifically, Simon Blackburn suggested in an article in 1984 that since Fodor explains the learning of natural languages as a process of formation and confirmation of hypotheses in the LOT, this leaves him open to the question of why the LOT itself should not be considered as just such a language which requires yet another and more fundamental representational substrate in which to form and confirm hypotheses so that the LOT itself can be learned. If natural language learning requires some representational substrate (the LOT) in order for it to be learned, why shouldn't the same be said for the LOT itself and then for the representational substrate of this representational substrate and so on, ad infinitum? On the other hand, if such a representational substrate is not required for the LOT, then why should it be required for the learning of natural languages? In this case, the LOT would be superfluous.[22] Fodor, in response, argues that the LOT is unique in that it does not have to be learned via an antecedent language because it is innate.

Yet another argument against the LOT was formulated by Daniel Dennett in 1981. The basic point of this argument is that it would seem, on the basis of the evidence of our behavior toward computers but also with regard to some of our own unconscious behavior, that explicit representation is not necessary for the explanation of propositional attitudes. During a game of chess with a computer program, we often attribute such attitudes to the computer, saying such things as "It thinks that the queen should be moved to the left". We attribute propositional attitudes to the computer and this helps us to explain and predict its behavior in various contexts. Yet no one would suggest that the computer is actually thinking or believing somewhere inside its circuits the equivalent of the propositional attitude "I believe I can kick this guy's butt" in Mentalese. The same is obviously true, suggests Dennett, of many of our everyday automatic behaviors such as "desiring to breathe clear air" in a stuffy environment.[23]

Fodor's self-proclaimed "extreme" concept nativism has been criticized by some linguists and philosophers of language. Kent Bach, for example, takes Fodor to task for his criticisms of lexical semantics and polysemy. Fodor claims that there is no lexical structure to such verbs as "keep", "get", "make" and "put". He suggests that, alternatively, "keep" simply expresses the concept KEEP (Fodor capitalizes concepts to distinguish them from properties, names or other such entities). If there is a straightforward one-to-one mapping between individual words and concepts, "keep your clothes on", "keep your receipt" and "keep washing your hands" will all share the same concept of KEEP under Fodor's theory. This concept presumably locks on to the unique external property of keeping. But, if this it true, then RETAIN must pick out a different property in RETAIN YOUR RECEIPT, since one can't retain one's cloths or retain washing one's hands. Fodor's theory also has a problem explaining how the concept FAST contributes, differently, to the contents of FAST CAR, FAST DRIVER, FAST TRACK, and FAST TIME.[24] Whether or not the differing interpretations of "fast" in these sentences are specified in the semantics of English, or are the result of pragmatic inference, is a matter of debate.[25] Fodor's own response to this kind of criticism is expressed bluntly in Concepts: "People sometimes used to say that exist must be ambiguous because look at the difference between 'chairs exist' and 'numbers exist'. A familiar reply goes: the difference between the existence of chairs and the existence of numbers seems, on reflection, strikingly like the difference between numbers and chairs. Since you have the latter to explain the former, you don't also need 'exist' to be polysemic."[26]

What makes Fodor's view of concepts difficult to accept for some critics is simply his insistence that such a large, perhaps implausible, number of them are primitive and undefinable. For example, Fodor considers such concepts as EFFECT, ISLAND, TRAPEZOID, and WEEK to be all primitive, innate and unanalyzable because they all fall into the category of what he calls "lexical concepts" (those for which our language has a single word). Against this view, Bach argues that the concept VIXEN is almost certainly composed out of the concepts FEMALE and FOX, BACHELOR out of SINGLE and MALE, and so on.[24]

See also

References

- ^ Norfleet, Phil. "Consciousness Concepts of Jerry Fodor".

- ^ McGinn, Colin (2002). The Making of a Philosopher. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-019792-7.

- ^ Fodor, Jerry. "Curriculum Vitae".

- ^ a b c Fodor, Jerry A. (1981). Representations: Philosophical Essays on the Foundations of Cognitive Science. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-06079-5.

- ^ Carnap, Rudolf (1947). Meaning and Necessity. Chicago: Chicago University Press. ISBN ISBN 0-226-09347-6.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Field, H.H. (1978). "Mental Representation". Erkenntnis. 13 (13): 9–61. doi:10.1007/BF00160888.

- ^ Harman, G. (1982). "Conceptual Role Semantics". Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic. 23 (23): 242–256. doi:10.1305/ndjfl/1093883628.

- ^ Frege, G. (1892). "Über Sinn und Bedeutung". Zeitschrift für Philosophie und philosophische Kritik.; trans. it. Senso e denotatione, in A. Bonomì, La Struttura Logica del Linguaggio, Bompiani, Milan 1973, pp 9-32

- ^ a b Francesco Ferretti (2001). Jerry A. Fodor:Mente e Linguaggio. Rome: Editori Laterza. ISBN 88-420-6220-0.

- ^ a b c Fodor, Jerry A. (1983). The Modularity of Mind:An Essay in Faculty Psychology. The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-56025-9.

- ^ Pinker, S (1997). How the Mind Works. New York: Norton.

- ^ Plotkin, H. (1997). Evolution in Mind. London: Alan Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9138-0.

- ^ Pylyshyn, Z. (1984). Computation and Cognition. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- ^ Fodor, J. (2000). The Mind Doesn't Work That Way:The Scope and Limits of Computational Psychology. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-56146-8.

- ^ a b c d e Fodor, Jerry A. (1990). A Theory of Content and Other Essays. The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-56069-0.

- ^ Dennett, Daniel C. (1987). The Intentional Stance. The MIT Press.

- ^ Fodor, Jerry A. "Fodor's Guide to Mental Representations". Mind (94): 76–100.

- ^ a b c Fodor, J, (1978). RePresentations. Philosophical Essays on the Foundations of Cognitive Science. Mass.: The MIT Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Fodor, J. Holism: A Shopper's Guide, (with E. Lepore), Blackwell, 1992, ISBN 0-631-18193-8.

- ^ Putnam, Hilary (1988). Mind, Language and Reality. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Fodor, Jerry. "The Mind/Body Problem". Scientific American (244): 124–132.

- ^ Blackburn, S. (1984). Spreading the Word. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Dennett, D.C. (1981). Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology. MIT Press.

- ^ a b Bach, Kent. "Review of Concepts: Where Cognitive Science Went Wrong". San Diego Review.

- ^ Pustejovsky, J. (1995). "The Generative Lexicon". MIT Press.

- ^ Fodor, J. (1998). Concepts: Where Cognitive Science Went Wrong (online PDF text). Oxford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 0-19-823636-0.

Books

- LOT 2: The Language of Thought Revisited, Oxford University Press, 2008

- Hume Variations, Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-19-928733-3.

- The Compositionality Papers , (with E. Lepore), Oxford University Press 2002, ISBN 0-19-925216-5.

- The Mind Doesn't Work That Way: The Scope and Limits of Computational Psychology, MIT Press, 2000, ISBN 0-262-56146-8.

- In Critical Condition, MIT Press, 1998, ISBN 0-262-56128-X.

- Concepts: Where Cognitive Science Went Wrong, (The 1996 John Locke Lectures), Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-19-823636-0.

- The Elm and the Expert, Mentalese and its Semantics, (The 1993 Jean Nicod Lectures), MIT Press, 1994, ISBN 0-262-56093-3.

- Holism: A Consumer Update, (ed. with E. Lepore), Grazer Philosophische Studien, Vol 46. Rodopi, Amsterdam, 1993, ISBN 90-5183-713-5.

- A Theory of Content and Other Essays, MIT Press, 1990, ISBN 0-262-56069-0.

- Psychosemantics: The Problem of Meaning in the Philosophy of Mind, MIT Press, 1987, ISBN 0-262-56052-6.

- The Modularity of Mind: An Essay on Faculty Psychology, MIT Press, 1983, ISBN 0-262-56025-9.

- Representations: Essays on the Foundations of Cognitive Science, Harvard Press (UK) and MIT Press (US), 1979, ISBN 0-262-56027-5.

- The Language of Thought, Harvard University Press, 1975, ISBN 0-674-51030-5.

- The Psychology of Language, with T. Bever and M. Garrett, McGraw Hill, 1974, ISBN 0-394-30663-5.

- Psychological Explanation, Random House, 1968, ISBN 0-07-021412-3.

- The Structure of Language, with Jerrold Katz (eds.), Prentice Hall, 1964, ISBN 0-13-854703-3.

External links

- Jerry Fodor's Homepage

- Jerry Fodor's profile at the LRB

- Semantics - An Interview with Jerry Fodor, ReVEL. Vol. 5, n. 8 (March 2007).