Omnipotence paradox

The omnipotence paradox is a philosophical paradox which arises when attempting to apply logic to the notion of an omnipotent being. The paradox is based around the question of whether or not an omnipotent being is able to perform actions that would limit its own omnipotence, thus becoming non-omnipotent. Some philosophers see this argument as proof of the impossibility of the existence of any such entity; others assert that the paradox arises from a misunderstanding or mischaracterization of the concept of omnipotence. In addition, several philosophers have considered the assumption that a being is either omnipotent or non-omnipotent to be a false dilemma, as it neglects the possibility of varying degrees of omnipotence (Haeckel).

Often, the paradox is formulated in terms of the God of the Abrahamic religions, though this is not a requirement. Since the Middle Ages, philosophers have phrased the paradox in many ways, of which the classic example is, "Could an omnipotent being create a rock so heavy that even that being could not lift it?" This particular statement has subtle flaws (discussed below), but as the most famous version, it still serves adequately for illustrating the different ways the paradox has been analyzed.

In order to analyze the omnipotence paradox in a rigorous way, one must first establish the precise definition of omnipotence. The definition of omnipotence varies amongst cultures and religions, and from one philosopher to another. A common definition is "all-powerful", but that is insufficient for the omnipotence paradox. This paradox cannot be formulated, for example, if one defines omnipotence as the ability to operate outside the constraints of any logical framework. Modern approaches to the problem have involved the study of semantics, debating whether language—and therefore philosophy—can meaningfully address the concept of omnipotence itself.

Definition of omnipotence

This section only defines omnipotence for the purposes of this article. For more uses, see the main article at Omnipotence.

Omnipotence in the context of an omnipotence paradox has several meanings. It is the power "to bring about any state of affairs" (Hoffman). However, the scope of such affairs is open to debate. Some philosophers, such as Descartes, maintain that the definition of omnipotence includes the ability to bring about logically impossible events. For example, it is logically impossible in the finite universe for a cube to be shapeless, or for 1 to equal 2 in the commonly used number system. For an omnipotent being to create a shapeless cube would prove that it is in fact possible, and that such a being is not bound by the laws of logic. Other philosophers, such as Aquinas, claim that a being does not have to do the logically impossible in order to still be omnipotent (Hoffman). In such cases, an omnipotent being has the power to do anything that is logically possible. The distinction between the two ways of thinking is important when attempting to resolve the omnipotence paradox, as it provides a limitation to the meaning of omnipotence.

Omnipotence can be applied to an entity in different ways. An essentially omnipotent being is an entity that is always omnipotent. In contrast, an accidentally omnipotent being is an entity that can be omnipotent for a temporary period of time, and then becomes non-omnipotent. The omnipotence paradox can be applied differently to each type of being (Hoffman).

Philosophical responses

A common example of the omnipotence paradox is expressed in the question, "Could an omnipotent being create a stone that it could not lift?" It is possible to analyze this question in the following manner:

- The being can either create a stone which it cannot lift, or it cannot create a stone which it cannot lift.

- If the being can create a stone which it cannot lift, then it is not omnipotent.

- If the being cannot create a stone which it cannot lift, then it is not omnipotent.

This mirrors the solution to another classic paradox, the irresistible force paradox: What happens when an irresistible force meets an immovable object? A response to this paradox is that if a force is irresistible, then by definition there is no truly immovable object; conversely, if an immovable object were to exist, then no force could be defined as being truly irresistible. This treatment of the paradox remains true to the basic assertions, but does not address the issue of the definition of omnipotence. Furthermore, the omnipotence paradox is related to another similar philosophical question, the grandfather paradox. The vernacular definition of omnipotence often seems to include the ability to travel across time; one could then ask the question, "Can an omnipotent being go back in time and kill his own grandfather?" This is not, however, a logically satisfactory analysis of the paradox, as it tends to focus on the imposition of human attributes onto a being that is not necessarily of human form (Wierenga).

One can also attempt to resolve the paradox by postulating that omnipotence does not necessarily demand that a being must be able to do all things at all times. Thus, one reasons,

- The being can create a stone which it cannot at that moment lift.

- However, being omnipotent, the being can always later reduce the weight of the stone to a weight where it can lift it. Therefore the being is still legitimately omnipotent.

This is essentially the same view espoused by Matthew Harrison Brady, a character in Inherit the Wind loosely based upon William Jennings Bryan. In the climactic scene of the 1960 movie version, Brady argues, "Natural law was born in the mind of the Creator. He can change it—cancel it—use it as He pleases!" Changing a stone's weight is logically equivalent to changing the effect of gravity (at least upon that one stone). Given this reasoning, one can debate the paradox yet again: can an omnipotent being create a stone so immutable that the being itself cannot reduce the stone's weight? Furthermore, does this situation impose a requirement on the omnipotent being—i.e., that it later reduce the stone's weight—thereby limiting the omnipotent being's free will?

The classic statement of the "irresistible force" paradox suffers from shortcomings when viewed in the context of modern physics, for a cannonball which cannot be deflected and a wall which cannot be knocked down are both objects of the same impossible type, that is, objects of infinite inertia. However, this is a statement of physics, which does not directly address the logic of the paradox; it only influences the choice of philosophical examples that we use to illustrate it. Likewise, the classic statement of the omnipotence paradox—a rock so heavy that its omnipotent creator cannot lift it—is grounded in Aristotelian science. This statement assumes both a geocentric cosmos and a flat Earth—can a stone only be "lifted" relative to the surface of the planet? Furthermore, if one considers the stone's position relative to the sun around which the planet orbits, one could hold that the stone is constantly being lifted. Pedantically speaking, modern physics indicates that the choice of phrasing about lifting stones may be a poor one; however, this does not in itself invalidate the fundamental concept of the generalized omnipotence paradox. Following Stephen Hawking's contemplations of the relation between a creator deity and natural law, one might modify the classic statement as follows:

- An omnipotent being creates a universe which follows the laws of Aristotelian physics.

- Within this universe, can the omnipotent being create a stone so heavy that the being cannot lift it?

Science writer James Gleick, in his biography of Richard Feynman, observes that the paradox arose when scientists began to debate the existence of atoms: could an omnipotent being—in this case, assumed to be the Christian God—create atoms that God Himself could not split?

Accidental omnipotence

If a being is accidentally omnipotent, then it can resolve the paradox:

- The omnipotent being creates a stone which it cannot lift (or "creates an atom it cannot split", et cetera).

- The omnipotent being cannot lift the stone, and becomes non-omnipotent.

Unlike essentially omnipotent entities, it is possible for an accidentally omnipotent being to be non-omnipotent. This does, however, raise the question of whether or not the being was ever omnipotent, or just capable of great power (Hoffman).

Essential omnipotence

If a being is essentially omnipotent, then it can resolve the paradox:

- The omnipotent being is essentially omnipotent, and therefore it is impossible for it to be non-omnipotent.

- Furthermore, the omnipotent being cannot do what is logically impossible.

- Creation of a stone which the omnipotent being cannot lift would be an impossibility, and therefore the omnipotent being is not required to do such a thing.

- The omnipotent being cannot create such a stone, but nevertheless retains its omnipotence.

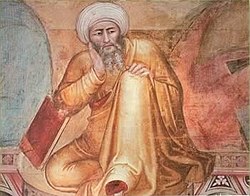

This necessarily accepts the view that even an omnipotent being cannot violate the laws of logic, and indeed this whole paradox can be seen as a strong reason for such a view. The philosopher Averroës advanced the omnipotence paradox for this reason (for which he was condemned by Bishop Tempier), although instead of phrasing it in terms of stones, he asked whether God could create a triangle with internal angles that did not add up to 180 degrees.

Note that the later discovery of non-Euclidean geometry does not resolve this question; for one might as well ask, "If given the axioms of Riemannian geometry, can an omnipotent being create a triangle whose angles do not add up to more than 180 degrees?" In either case, the real question is whether or not an omnipotent being would have the ability to evade the consequences which follow logically from a system of axioms that the being created.

For an overview of this formulation and the historical context in which it emerged, see James Burke's The Day the Universe Changed, either the second episode of the television series or the second chapter of the companion book. After the Reconquista, translations of Arab scientific and philosophical works—many of them in turn translations of Ancient Greek material—entered European intellectual society. When Averroës's conundrum reached Paris, it became part of a controversy which led to the University's theology students going on strike for six years. As Burke phrases the matter, "This 'limitations on God' stuff was dynamite."

Mainstream Catholic theology eventually reconciled itself to the Greek and Arabic material the Reconquista made available, thanks in large part to Thomas Aquinas, whose Summa Theologica affirmed the notion that God could not defy logic. In this respect, Aquinas follows the thinking of Maimonides, the twelfth-century Jewish philosopher and physician, who makes the same proposition in his Guide for the Perplexed. Maimonides was an adherent of negative theology, a discipline which holds that one can only describe God via negations. A somewhat mystical view, negative or "Apophatic" theology centers upon the concept that God's true essence cannot be spoken, and that all affirmative descriptions of God risk being blasphemous or heretical.

Ethan Allen, a guerrilla in the American Revolution, wrote a treatise entitled Reason: The Only Oracle of Man, which addresses the topics of original sin, theodicy and several others in classic Enlightenment fashion. In Chapter 3, section IV, he notes that "omnipotence itself" could not exempt animal life from mortality, since change and death are defining attributes of such life. He argues, "the one cannot be without the other, any more than there could be a compact number of mountains without valleys, or that I could exist and not exist at the same time, or that God should effect any other contradiction in nature." Labeled by his friends a Deist, Allen accepted the notion of a divine being, though throughout Reason he argues that even a divine being must be circumscribed by logic.

Logically impossible

Some philosophers maintain that the paradox can be resolved if the definition of omnipotence includes Descartes' view that an omnipotent being can do the logically impossible:

- An omnipotent being can do the logically impossible.

- The omnipotent being creates a stone which it cannot lift.

- The omnipotent being then lifts the stone.

Presumably, such a being could also make the sum 2 + 2 = 5 become mathematically possible, or could create a square circle. In the words of Harry Frankfurt, "If an omnipotent being can do what is logically impossible, then he can not only create situations which he cannot handle but also, since he is not bound by the limits of consistency, he can handle situations which he cannot handle."

However, this attempt to resolve the paradox is problematic in that the definition itself forgoes logical consistency. The paradox may be solved, but at the expense of rendering logic futile, unnecessary or meaningless in defining such a being since such a being transcends logic. Allen's Reason lampoons those who resolved paradoxes by abandoning logic. He writes, "if they argue without reason (which, in order to be consistent with themselves, they must do) they are out of the reach of rational conviction, nor do they deserve a rational argument."

Semantics

Many years later, the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein formalized Allen's attitude in the concluding pages of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Up until proposition 6.4, the Tractatus stays generally within the realm of logical positivism, but 6.41 and the succeeding propositions argue that ethics is a "transcendental" subject which we cannot examine with language, as it is a form of aesthetics and cannot be expressed. Wittgenstein then begins talking of the will, life after death, and God; he argues that all discussion of such issues is a misuse of logic. Specifically, since logical language can only reflect the world, any discussion of the mystical, that which lies outside of the metaphysical subject's world, is meaningless. This suggests that many of the traditional domains of philosophy—e.g., ethics and metaphysics—cannot in fact be discussed meaningfully. Any attempt to discuss them immediately loses all sense. This also suggests that Wittgenstein's own project of trying to explain language is impossible, for exactly these reasons, and so he suggests that the project of philosophy must ultimately be abandoned for those logical practices which attempt to reflect the world, not what is outside of it.

Wittgenstein's work makes the omnipotence paradox a problem in semantics, the study of how symbols are given meaning. (The retort "That's only semantics" is a way of saying that a statement only concerns the definitions of words, instead of anything important in the physical world.) According to the Tractatus, then, even attempting to formulate the omnipotence paradox is futile, since language cannot refer to the entities the paradox considers. The final proposition of the Tractatus gives Wittgenstein's dictum for these circumstances: "What we cannot speak of, we must pass over in silence."

One should note that in his later years, Wittgenstein himself revised or renounced outright much of what he wrote in the Tractatus. His second major work, Philosophical Investigations (published posthumously), argues that many philosophical problems which had seemingly been intractable to logical analysis are in truth artifacts of the way philosophers misuse language. Typically, commentators divide Wittgenstein's work into "early" and "late" periods, though beyond this simple distinction, it is difficult to find any consensus among Wittgenstein's interpreters.

Pop culture and humorous responses

The omnipotence paradox has infiltrated popular culture. References to the omnipotence paradox and similar debates such as the existence of an omnipotent being can be found in a variety of media.

- In an episode of The Simpsons, Homer asks Ned Flanders, "Could Jesus microwave a burrito so hot that He Himself could not eat it?" Note that this formulation is immune to the questions of physics raised earlier, since modern concepts of inertia and relativity have not affected the definition of a burrito.

- Stephen Hawking's A Brief History of Time introduces the omnipotence paradox within a more general discussion of what role a creator deity might play in relation to natural laws. In a later book, Black Holes and Baby Universes, Hawking notes half-jokingly that including these religious speculations—including the book's last line, "for then we would know the mind of God"—probably doubled A Brief History's sales.

- The modern science of quantum mechanics postulates that all material objects naturally exist in a superposition of states. Though the basic equations of quantum mechanics can be interpreted in several different ways, a common viewpoint states that when an object is "observed" or "measured", it "collapses" into a single state. Many calculations in quantum mechanics are intended to determine the probability with which an object will collapse into one state or another. This concept has led to a tongue-in-cheek solution for the omnipotence paradox, in the tradition of physicist humor exemplified by Schrödinger's cat. If an omnipotent being is in fact omnipotent, it can prevent others from observing it. Such a being could then both create a stone it cannot lift and lift the stone at the same time, and because others could not observe it doing so, there would be no way to confirm the outcome of events. Greg Egan's novel Quarantine explores some of these issues in a fictional context.

See also

References

- External links in the following were last verified 16 November 2005.

- Haeckel, Ernst. The Riddle of the Universe. Harper and Brothers, 1900.

- Hoffman, Joshua, Rosenkrantz, Gary. "Omnipotence" The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2002 Edition). Edward N. Zalta (ed.) [1]

- Wierenga, Edward. "Omnipotence" The Nature of God: An Inquiry into Divine Attributes. Cornell University Press, 1989. [2]

- Gleick, James. Genius. Pantheon, 1992. ISBN 0-679-40836-3.

- Burke, James. The Day the Universe Changed. Little, Brown; 1995 (paperback edition). ISBN 0-316-11704-8.

- Allen, Ethan. Reason: The Only Oracle of Man. J.P. Mendum, Cornill; 1854. Originally published 1784, available online.

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Available online via Project Gutenberg.