John Marshall

John Marshall | |

|---|---|

| |

| 4th Chief Justice of the United States | |

| In office February 4, 1801 – July 6, 1835 | |

| Nominated by | John Adams |

| Preceded by | Oliver Ellsworth |

| Succeeded by | Roger B. Taney |

| 4th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office June 13, 1800 – March 13, 1801 | |

| President | John Adams |

| Preceded by | Timothy Pickering |

| Succeeded by | James Madison |

| U.S. Representative from Virginia | |

| In office March 4, 1799 – June 7, 1800 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 24, 1755 Germantown, Colony of Virginia |

| Died | July 6, 1835 (aged 79) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.A. |

| Political party | Federalist |

| Spouse | Mary Willis Ambler |

| Profession | Lawyer, Judge |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Culpeper, Virginia Militia |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War |

John Marshall (September 24, 1755 – July 6, 1835) was an American statesman and jurist who shaped American constitutional law and made the Supreme Court a center of power. Marshall was Chief Justice of the United States, serving from February 4, 1801, until his death in 1835. He served in the United States House of Representatives from March 4, 1799, to June 7, 1800, and, under President John Adams, was Secretary of State from June 6, 1800, to March 4, 1801. Marshall was from the Commonwealth of Virginia and a leader of the Federalist Party.

The longest serving Chief Justice in Supreme Court history, Marshall dominated the Court for over three decades (a term outliving his own Federalist Party) and played a significant role in the development of the American legal system. Most notably, he established that the courts are entitled to exercise judicial review, the power to strike down laws that violate the Constitution. Thus, Marshall has been credited with cementing the position of the judiciary as an independent and influential branch of government. Furthermore, Marshall made several important decisions relating to Federalism, shaping the balance of power between the federal government and the states during the early years of the republic. In particular, he repeatedly confirmed the supremacy of federal law over state law and supported an expansive reading of the enumerated powers.

Early years

John Marshall was born in a log cabin near Germantown, a rural community on the Virginia frontier, in what is now Fauquier County near Midland, Virginia, to Thomas Marshall and Mary Randolph Keith. From a young age, he was noted for his good humor and black eyes, which were "strong and penetrating, beaming with intelligence and good nature".[1] Marshall served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War and was friends with George Washington. He served first as a Lieutenant in the Culpeper Minute Men from 1775 to 1776, then as a Lieutenant in the Eleventh Virginia Continental Regiment from 1776 to 1780.[2] During his time in the army, he enjoyed running races with the other soldiers and was nicknamed "Silverheels" for the white heels his mother had sewn into his stockings.[3] After his time in the Army, he read law under the famous Chancellor George Wythe in Williamsburg, Virginia at the College of William and Mary,[4] and was admitted to the Bar in 1780.[2] He was in private practice in Fauquier County, Virginia[2] before entering politics.

State political career

In 1782 Marshall won a seat in the Virginia House of Delegates, in which he served until 1789 and again from 1795–1796. The Virginia General Assembly elected him to serve on the Council of State later in the same year. In 1785, Marshall took up the additional office of Recorder of the Richmond City Hustings Court.[5]

In 1788, Marshall was selected as a delegate to the Virginia convention responsible for ratifying or rejecting the United States Constitution, which had been proposed by the Philadelphia Convention a year earlier. Together with James Madison and Edmund Randolph, Marshall led the fight for ratification. He was especially active in defense of Article III, which provides for the Federal judiciary.[6] His most prominent opponent at the ratification convention was Anti-Federalist leader Patrick Henry. Ultimately, the convention approved the Constitution by a vote of 89-79. Marshall identified with the new Federalist Party (which supported a strong national government and commercial interests), rather than Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party (which advocated states' rights and idealized the yeoman farmer and the French Revolution).

Meanwhile, Marshall's private law practice continued to flourish. He successfully represented the heirs of Lord Fairfax in Hite v. Fairfax (1786), an important Virginia Supreme Court case involving a large tract of land in the Northern Neck of Virginia. In 1796, he appeared before the United States Supreme Court in another important case, Ware v. Hylton, a case involving the validity of a Virginia law providing for the confiscation of debts owed to British subjects. Marshall argued that the law was a legitimate exercise of the state's power; however, the Supreme Court ruled against him, holding that the Treaty of Paris required the collection of such debts.[7]

In 1795, Marshall declined Washington's offer of Attorney General of the United States and, in 1796, declined to serve as minister to France. In 1797, he accepted when President John Adams appointed him to a three-member commission to represent the United States in France. (The other members of this commission were Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Elbridge Gerry.) However, when the envoys arrived, the French refused to conduct diplomatic negotiations unless the United States paid enormous bribes. This diplomatic scandal became known as the XYZ Affair, inflaming anti-French opinion in the United States. Hostility increased even further when the Directoire expelled Marshall and Pinckney from France. Marshall's handling of the affair, as well as public resentment toward the French, made him popular with the American public when he returned to the United States.[7]

In 1798, Marshall declined a Supreme Court appointment, recommending Bushrod Washington, who would later become one of Marshall's staunchest allies on the Court.[8] In 1799, Marshall reluctantly ran for a seat in the United States House of Representatives. Although his congressional district (which included the city of Richmond) favored the Democratic-Republican Party, Marshall won the race, in part due to his conduct during the XYZ Affair and in part due to the support of Patrick Henry. His most notable speech was related to the case of Thomas Nash (alias Jonathan Robbins), whom the government had extradited to Great Britain on charges of murder. Marshall defended the government's actions, arguing that nothing in the Constitution prevents the United States from extraditing one of its citizens.[9]

On May 7, 1799, President Adams nominated Congressman Marshall as Secretary of War. However, on May 12, Adams withdrew the nomination, instead naming him Secretary of State, as a replacement for Timothy Pickering. Confirmed by the United States Senate on May 13, Marshall took office on June 6, 1800. As Secretary of State, Marshall directed the negotiation of the Convention of 1800, which ended the Quasi-War with France and brought peace to the new nation.

The Marshall Court from 1801 to 1835

Marshall was thrust into the office of Chief Justice in the wake of the presidential election of 1800. With the Federalists soundly defeated and about to lose both the executive and legislative branches to Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans, President Adams and the lame duck Congress passed what came to be known as the Midnight Judges Act, which made sweeping changes to the federal judiciary, including a reduction in the number of Justices from six to five so as to deny Jefferson an appointment until two vacancies occurred.[10] As the incumbent Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth was in poor health, Adams first offered the seat to ex-Chief Justice John Jay, who declined on the grounds that the Court lacked "energy, weight, and dignity."[11] Jay's letter arrived on January 20, 1801, and as there was precious little time left, Adams nominated Marshall, who was with him at the time and able to accept immediately. The Senate at first delayed, hoping to Adams would make a different choice, but recanted "lest another not so qualified, and more disgusting to the Bench, should be substituted, and because it appeared that this gentleman was not privy to his own nomination".[12] Marshall was confirmed by the Senate on January 27, 1801, and received his commission on January 31, 1801.[2] While Marshall officially took office on February 4, at the request of the President he continued to serve as Secretary of State until Adams' term expired on March 4.

Soon after becoming Chief Justice, Marshall revolutionized the manner in which the Supreme Court announced its decisions. Previously, each Justice would author a separate opinion (known as a seriatim opinion), as is still done in the 20th and 21st centuries in such jurisdictions as the United Kingdom and Australia. Under Marshall, however, the Supreme Court adopted the practice of handing down a single opinion of the Court. As Marshall was almost always the author of this opinion, he essentially became the Court's sole mouthpiece in important cases. His forceful personality allowed him to dominate his fellow Justices; only once did he find himself on the losing side. (The case of Ogden v. Saunders, in 1827, was the sole constitutional case in which he dissented from the majority.)[8]

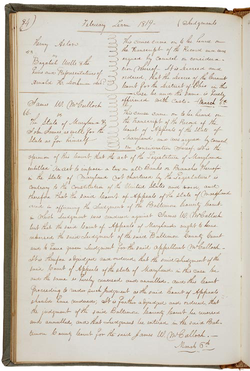

The first important case of Marshall's career was Marbury v. Madison (1803), in which the Supreme Court invalidated a provision of the Judiciary Act of 1789 on the grounds that it violated the Constitution by attempting to expand the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. Marbury was the first case in which the Supreme Court ruled an act of Congress unconstitutional; it firmly established the doctrine of judicial review. The Court's decision was opposed by President Thomas Jefferson, who lamented that this doctrine made the Constitution "a mere thing of wax in the hands of the judiciary, which they may twist and shape into any form they please."[13]

In 1807, he presided, with Judge Cyrus Griffin, at the great state trial of former Vice President Aaron Burr, who was charged with treason and misdemeanor. Prior to the trial, President Jefferson condemned Burr and strongly supported conviction. Marshall, however, narrowly construed the definition of treason provided in Article III of the Constitution; he noted that the prosecution had failed to prove that Burr had committed an "overt act," as the Constitution required. As a result, the jury acquitted the defendant, leading to increased animosity between the President and the Chief Justice.[14]

During the 1810s and 1820s, Marshall made a series of decisions involving the balance of power between the federal government and the states, where he repeatedly affirmed federal supremacy. For example, he established in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) that states could not tax federal institutions and upheld congressional authority to create the Second Bank of the United States, even though the authority to do this was not expressly stated in the Constitution. Also, in Cohens v. Virginia (1821), he established that the Federal judiciary could hear appeals from decisions of state courts in criminal cases as well as the civil cases over which the court had asserted jurisdiction in Martin v. Hunter's Lessee (1816). Justices Bushrod Washington and Joseph Story proved to be his strongest allies in these cases, whereas Smith Thompson was a strong opponent to Marshall.

As the young nation was endangered by regional and local interests that often threatened to fracture its hard-fought unity, Marshall repeatedly interpreted the Constitution broadly so that the Federal Government had the power to become a respected and creative force guiding and encouraging the nation's growth. Thus, for all practical purposes, the Constitution in its most important aspects today is the Constitution as John Marshall interpreted it. As Chief Justice, he embodied the majesty of the judiciary of the government as fully as the President of the United States stood for the power of the Executive Branch.

Marshall wrote several important Supreme Court opinions, including:

- Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803)

- Fletcher v. Peck, 10 U.S. 87 (1810)

- McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819)

- Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 U.S. 518 (1819)

- Cohens v. Virginia, 19 U.S. 264 (1821)

- Johnson v. M'Intosh, 21 U.S. 543 (1823)

- Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. 1 (1824)

- Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 (1832)

- Barron v. Baltimore, 32 U.S. 243 (1833)

Marshall served as Chief Justice through all or part of six Presidential administrations (John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson), and remained a stalwart advocate of Federalism and a nemesis of the Jeffersonian school of government throughout its heyday. He participated in over 1000 decisions, writing 519 of the opinions himself.[6]

He established the Supreme Court as the final authority on matters of constitutional law.[15]

His impact "on American constitutional law is peerless" and the totality of his work on the court has been likened to his being the "Babe Ruth" of the Supreme Court. "As the single most important figure on constitutional law, Marshall's imprint can still be fathomed in the great issues of contemporary America."[16]

Despite modesty and blandness, Marshall held strong views. He dominated the Court and "was personally responsible for elevating it to a position of real authority." Despite all that, he "often curbed" his personal opinions, preferring to arrive at decisions by consensus.[17] He adjusted his role to accommodate other members of the court as they developed.[18] His performance as chief justice established the paradigm for all chief justices who followed in his place.[17][18]

President John Adams offered this appraisal of Marshall's impact: "My gift of John Marshall to the people of the United States was the proudest act of my life."[19]

Biography of Washington

Marshall greatly admired George Washington, and wrote a highly influential biography. Between 1805 and 1807, he published a five-volume biography; his Life of Washington was based on records and papers provided him by the president's family. The first volume was reissued in 1824 separately as A History of the American Colonies. The work reflected Marshall's Federalist principles. His revised and condensed two-volume Life of Washington was published in 1832.[20] Historians have often praised its accuracy and well-reasoned judgments, while noting his frequent paraphrases of published sources such as William Gordon's 1801 history of the Revolution and the British Annual Register.[21]

Other work, later life, legacy

Marshall loved his home, built in 1790, in Richmond, Virginia,[22] and spent as much time there as possible in quiet contentment.[23][24] While in Richmond he attended St. John's Church in Church Hill until 1814 when he led the movement to hire Robert Mills as architect of Monumental Church, which commemorated the death of 72 Virginians. The Marshall family occupied pew No. 23 at Monumental Church and entertained the Marquis de Lafayette there during his visit to Richmond in 1824. For approximately three months each year, however, he would be away in Washington for the Court's annual term; he would also be away for several weeks to serve on the circuit court in Raleigh, North Carolina.

In 1823, he became first president of the Richmond branch of the American Colonization Society, which was dedicated to resettling freed American slaves in Liberia, on the West coast of Africa.

In 1828, he presided over a convention to promote internal improvements in Virginia.

In 1829, he was a delegate to the state constitutional convention, where he was again joined by fellow American statesman and loyal Virginians, James Madison and James Monroe, although all were quite old by that time. Marshall mainly spoke at this convention to promote the necessity of an independent judiciary.

On December 25, 1831, Mary, his beloved wife of some 49 years, died. Most who knew Marshall agreed that after Mary's death, he was never quite the same.

On returning from Washington in the spring of 1835, he suffered severe contusions resulting from an accident to the stage coach in which he was riding.[25] His health, which had not been good for several years, now rapidly declined, and in June he journeyed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania for medical attendance. There he died on July 6, at the age of 79, having served as Chief Justice for over 34 years. He also was the last surviving member of John Adams's Cabinet and the second to last surviving Founding Father, the last being James Madison.

Two days before his death, he enjoined his friends to place only a plain slab over his and his wife's graves, and he wrote the simple inscription himself. His body, which was taken to Richmond, lies in Shockoe Hill Cemetery in a well kept grave.[26]

JOHN MARSHALL

Son of Thomas and Mary Marshall

was born the 24th of September 1755

Intermarried with Mary Willis Ambler

the 3rd of January 1783

Departed this life

the 6th day of July 1835.[27]

Monuments and memorials

Marshall's home in Richmond, Virginia, has been preserved by APVA Preservation Virginia. It is considered to be an important landmark and museum, essential to an understanding of the Chief Justice's life and work.[28] See, John Marshall House.

The United States Bar Association commissioned sculptor William Wetmore Story to execute the statue of Marshall that now stands [sits] inside the Supreme Court on the ground floor.[29][30] Another casting of the statue is located at Constitution Ave. and 4th Street in Washington D.C. and a third on the grounds of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Story's father Joseph Story had served as an Associate Justice on the United States Supreme Court with Marshall. The statue was originally dedicated in 1884.[31]

An engraved portrait of Marshall appears on U.S. paper money on the series 1890 and 1891 treasury notes. These rare notes are in great demand by note collectors today. Also, in 1914, an engraved portrait of Marshall was used as the central vignette on series 1914 $500 federal reserve notes. These notes are also quite scarce. Example of both notes are available for viewing on the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco website.[32][33]

Having grown from a Reformed Church academy, Marshall College, named upon the death of Chief Justice John Marshall, officially opened in 1836 with a well-established reputation. After a merger with Franklin College in 1853, the school was renamed Franklin and Marshall College. The college went on to become one of the nation's foremost liberal arts colleges.

Four law schools and one University today bear his name: The Marshall-Wythe School of Law at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia; The Cleveland-Marshall College of Law in Cleveland, Ohio; John Marshall Law School in Atlanta, Georgia; and, The John Marshall Law School in Chicago, Illinois. The University that bears his name is Marshall University in Huntington West Virginia. Marshall County, Illinois, Marshall County, Indiana,Marshall County, Kentucky and Marshall County, West Virginia are also named in his honor. A number of high schools around the nation have also been named for him.

John Marshall's birthplace in Fauquier County is a park, the John Marshall Birthplace Park, and a marker can be seen on Route 28 noting this place and event.

Marshall, Michigan was named by town founders Sidney and George Ketchum in honor of the Chief Justice of the United States John Marshall from Virginia—whom they greatly admired. Occurring five years before Marshall's death, it was the first of dozens of communities and counties named for him.[34] Marshalltown, Iowa was allegedly named for the Michigan city, but adopted its current name because there was already a Marshall, Iowa[35]

John Marshall was an active Freemason and served as Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Prominent family connections

- Humphrey Marshall (1760 – July 3, 1841) -- a United States Senator from Kentucky -- is the first cousin and brother-in-law of the chief justice.

- Thomas Francis Marshall (June 7, 1801 – September 22, 1864) was a nineteenth century politician and lawyer who was elected U.S. Representative from Kentucky. He is a nephew of the Chief Justice.

- George Marshall (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American military leader, General of the U.S. Army, Chief of Staff of the Army, Secretary of State, and the third Secretary of Defense. He was the 'father' of the Marshall Plan, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. He is a distant relative of the chief justice.

- Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) primary author of the U.S. Declaration of Independence and President of the United States. He is a distant cousin of Marshall on his mother's side.

Bibliography

- Baker, Leonard, (1974) John Marshall: A Life in Law (New York: Macmillan). KF8745 M3 B3.

- Beveridge, Albert J. The Life of John Marshall, in 4 volumes (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1919), winner of the Pulitzer Prize, Volume I, Volume II, Volume III and Volume IV at Internet Archive.

- Corwin, Edward W., (1919) John Marshall and the Constitution: A Chronicle of the Supreme Court, Yale University Press, online Edition at Project Gutenberg

- Hobson, Charles. The Great Chief Justice: John Marshall and the Rule of Law (University Press of Kansas, 1996). ISBN 0700607889; ISBN 978-0700607884.

- Johnson, Herbert Alan, "John Marshall" in Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel, eds. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions — Vol. 1 (1997) pp 180–200. ISBN 0-313-27932-2.

- Johnson, Herbert A. The Chief Justiceship of John Marshall from 1801 to 1835. University of South Carolina Press, 1998. 352 pp. ISBN 1570031215; ISBN 978-1570031212.

- Newmyer, R. Kent. John Marshall and the Heroic Age of the Supreme Court Louisiana State University Press, 2001. 511 pp.[36] ISBN 0-8071-2701-9; ISBN 978-0-8071-2701-8.

- Newmyer, R. Kent, (1968) The Supreme Court under Marshall and Taney, University of Connecticut.

- Robarge, David. (2000) A Chief Justice's Progress: John Marshall from Revolutionary Virginia to the Supreme Court. (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press). 366 pp. ISBN 9780313308581.

- Rudko, Frances H., (1991) John Marshall, Statesman, and Chief Justice (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press). ISBN 0-313-27932-2.

- Shevory, Thomas C.; John Marshall's Law: Interpretation, Ideology, and Interest Greenwood Press, 1994. ISBN 0-313-27932-2.

- Simon, James F. What Kind of Nation: Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, and the Epic Struggle to Create a United States. Simon & Schuster, 2002. 348 pp ISBN 0684848716; ISBN 9780684848716.

- Smith, Jean Edward, (1996) John Marshall: Definer Of A Nation, Henry Holt and Company. 736 pp. ISBN 080501389X; ISBN 978-0805013894.

- Stites, Francis N., (1981) John Marshall: Defender of the Constitution (Boston: Little, Brown). ISBN 0673393534; ISBN 978-0673393531.

- White, Edward. The Marshall Court and Cultural Change, 1815-1835 Macmillan, 1988. 1009 pp; abridged ed. Oxford University Press, 1991. 864 pp. ISBN 0195070585; ISBN 978-0195070583

Primary sources

- Cotton, Joseph Peter, Jr., ed., (1905) Constitutional Decisions of John Marshall, (New York and London).

- Hobson, Charles F.; Perdue, Susan Holbrook; and Lovelace, Joan S., eds. The Papers of John Marshall published by University of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture; the standard scholarly edition; most recent volume: Vol. 11: Correspondence, Papers, and Selected Judicial Opinions, April 1827–December 1830. (2002) ISBN 0815311761.

- Story, Joseph, ed., The Writings of John Marshall, late Chief Justice of the United States, upon the Federal Constitution, Boston, 1839 at Google books.

Notes

- ^ Quoted in Baker (1972), p. 4 and Stites (1981), p. 7.

- ^ a b c d John Marshall at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- ^ Stites (1981), pp. 11-15.

- ^ Courthouse History, U.S. District Court, Washington, DC.

- ^ "Marshall, John." Federal Judicial Center.

- ^ a b "John Marshall" Encyclopædia Britannica, from Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite 2004 DVD. Copyright © 1994–2003 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. May 30, 2003

- ^ a b "Marshall, John." (1888). Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- ^ a b Ariens, Michael. "John Marshall."

- ^ "Marshall, John." (1911) Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. London: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Stites (1981), pp. 77-80.

- ^ Goldman, Jerry. "John Jay." OYEZ Project.

- ^ Quoted in Stites (1981), p. 80.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas. Letter to Spencer Roane.

- ^ Linder, Doug. "The Treason Trial of Aaron Burr."

- ^ John Marshall at Supreme Court Historical Society.

- ^ Oyez Project, Supreme Court media, John Marshall.

- ^ a b Fox, John, Expanding Democracy, Biographies of the Robes, John Marshall. Public Broadcasting Service.

- ^ a b Newmyer, R. Kent. John Marshall at Answers.com.

- ^ The Marshall Court, 1801-1835, Supreme Court Historical Society.

- ^ Marshall, John; Widger, David, Ed., Life of Washington (Document No. 28859 -- Release Date 2009-05-18) at Project Gutenberg.

- ^ William A. Foran, "John Marshall as a Historian," American Historical Review, Vol. 43, No. 1 (October, 1937), pp. 51-64 in JSTOR

- ^ John Marshall House, Richmond, Virginia.

- ^ National Park Service, Marshall's Richmond home.

- ^ National Park Service, "The Great Chief Justice" at Home, Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- ^ Courthouse History, U.S. District Court, Washington, DC.

- ^ John Marshall at Find a Grave. See also, Christensen, George A. (2008) Here Lies the Supreme Court Revisited: Gravesites of the Justices. Supreme Court Historical Society. Journal of the Supreme Court, 33 Issue 1, Pages 17 - 41 (19 Feb 2008), University of Alabama.

- ^ *John Marshall at Find a Grave

- ^ National Park Service, "The Great Chief Justice" at Home, Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- ^ Exercises at the ceremony of unveiling the statue of John by Morrison Remick Waite, William Henry Rawle, Philadelphia Bar Association - 1884 - Biography & Autobiography - 92 pp., pages 1, 3, 5 9, 23-29.

- ^ Courthouse History, U.S. District Court, Washington, DC.

- ^ Exercises at the ceremony of unveiling the statue of John by Morrison Remick Waite, William Henry Rawle, Philadelphia Bar Association - 1884 - Biography & Autobiography - 92 pp., pages 1, 3, 5 9, 23-29.

- ^ Pictures of large size Federal Reserve Notes featuring John Marshall, provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

- ^ Pictures of US Treasury Notes featuring John Marshall, provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

- ^ City of Marshall, Michigan

- ^ Answers, source of Marshalltown name.

- ^ Online review, John Marshall and the Heroic Age of the Supreme Court.

References

- Lossing, Benson John (December 21, 2005) [1855]. Our countrymen, or, Brief memoirs of eminent Americans. Illustrated by one hundred and three portraits. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Scholarly Publishing Office, University of Michigan Library. ISBN 1-4255-4394-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Smith, Jean Edward (March 15, 1998) [1996]. John Marshall: Definer Of A Nation (Reprint edition ed.). New York, NY: Owl Books. ISBN 0-8050-5510-X.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)

- United States Congress. "John Marshall (id: M000157)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1568021267.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0791013774.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195058356.

- Martin, Fenton S. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0871875543.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 0815311761.

See also

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of places and things named for John Marshall

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Marshall Court

External links

- Works by John Marshall at Project Gutenberg

- The Life of George Washington, Vol. 1 (of 5) Commander in Chief of the American Forces During the War which Established the Independence of his Country and First President of the United States (English)

- The Life of George Washington, Vol. 2 (of 5)

- The Life of George Washington, Vol. 3 (of 5)

- The Life of George Washington, Vol. 4 (of 5)

- The Life of George Washington, Vol. 5 (of 5)

- Template:Worldcat id

- Bennett, Georgia, John and Tom — Rivals in Everything, Richmond Times-Dispatch, February 10, 1935

- John Marshall Foundation.

- Location of Papers of John Marshall, Judicial manuscripts.

- National Park Service, "The Great Chief Justice" at Home, Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan.

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1801-1804 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1804-1806 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1807-1810 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1810-1811 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1811-1812 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1812-1823 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1823-1826 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1826-1828 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1828-1829 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1830-1834 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1835 Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition

- American Episcopalians

- American Anglicans

- 19th-century American Episcopalians

- 18th-century American Episcopalians

- Chief Justices of the United States

- Continental Army officers from Virginia

- United States Secretaries of State

- Members of the Virginia House of Delegates

- Virginia lawyers

- British North American Anglicans

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Virginia

- Virginia Federalists

- People of the Quasi-War

- People from Richmond, Virginia

- People from Fauquier County, Virginia

- Phi Beta Kappa Society

- College of William and Mary alumni

- 1755 births

- 1835 deaths

- United States federal judges appointed by John Adams