Ketogenic diet

The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, adequate-protein, low-carbohydrate diet primarily used to treat difficult-to-control (refractory) epilepsy in children. The diet mimics aspects of starvation by forcing the body to burn fats rather than carbohydrates. Normally, the carbohydrates contained in food are converted into glucose, which is then transported around the body and is particularly important in fuelling brain function. However, if there is very little carbohydrate in the diet, the liver converts fat into fatty acids and ketone bodies. The ketone bodies pass into the brain and replace glucose as an energy source. An elevated level of ketone bodies in the blood, a state known as ketosis, leads to a reduction in the frequency of epileptic seizures.[1]

The diet provides just enough protein for body growth and repair, and sufficient calories to maintain the correct weight for age and height. The classic ketogenic diet contains a 4:1 ratio by weight of fat to combined protein and carbohydrate. This is achieved by excluding high-carbohydrate foods such as starchy fruits and vegetables, bread, pasta, grains and sugar, while increasing the consumption of foods high in fat such as cream and butter.[1]

Most dietary fat is made of molecules called long-chain triglycerides (LCTs). However, medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs)—made from fatty acids with shorter carbon chains than LCTs—are more ketogenic. A variant of the diet known as the MCT ketogenic diet uses a form of coconut oil, which is rich in MCTs, to provide around half the calories. As less overall fat is needed in this variant of the diet, a greater proportion of carbohydrate and protein can be consumed, allowing a greater variety of food choices.[2][3]

Developed in the 1920s, the ketogenic diet was widely used into the next decade, but its popularity waned with the introduction of effective anticonvulsant drugs. In the mid 1990s, Hollywood producer Jim Abrahams, whose son's severe epilepsy was effectively controlled by the diet, created the Charlie Foundation to promote it. Publicity included an appearance on NBC's Dateline programme and ...First Do No Harm (1997), a made-for-television film starring Meryl Streep. The foundation sponsored a multicentre research study, the results of which—published in 1996—marked the beginning of renewed scientific interest in the diet.[1]

The diet is effective in half of the patients who try it, and very effective in a third.[4] In 2008, a randomised controlled trial showed a clear benefit for treating refractory epilepsy in children with the ketogenic diet.[5] There is some evidence that adults with epilepsy may benefit from the diet, and that a less strict regime, such as a modified Atkins diet, is similarly effective.[1] The ketogenic diet has also been proposed as a treatment for a number of neurological conditions other than epilepsy; as of 2008, research in this area has yet to produce sufficient positive data to warrant clinical use.[4][6]

Epilepsy

Epilepsy, the second most common neurological disorder after stroke, is diagnosed in a person having recurrent unprovoked seizures. Epileptic seizures occur when cortical neurons fire excessively, hypersynchronously, or both, leading to temporary disruption of normal brain function. This might affect, for example, the muscles, the senses, consciousness, or a combination. A seizure might be focal, confined to one part of the brain, or generalised, spread widely throughout the brain and leading to a loss of consciousness. Epilepsy can occur for a variety of reasons; some forms have been classified into epileptic syndromes, most of which begin in childhood. Epilepsy is considered refractory to treatment when two or three anticonvulsant drugs have failed to control it. About 60% of patients will achieve control of their epilepsy with the first drug they use; about 30% do not achieve control with drugs, some of whom may be candidates for epilepsy surgery.[7]

History

The ketogenic diet is a mainstream therapy that was developed to reproduce the success and remove the limitations of the non-mainstream use of fasting to treat epilepsy.[Note 1] Although popular for a while, it was discarded when anticonvulsant drugs became available.[1] Most individuals with epilepsy can successfully control their seizures with medication. However, 20–30% fail to achieve such control despite trying a number of different drugs.[6] For this group, and for children in particular, the diet has once again found a role in epilepsy management.[1]

Fasting

The ancient Greek physicians treated diseases, including epilepsy, by altering their patient's diet. An early treatise concerning epilepsy, On the Sacred Disease, can be found in the Hippocratic Corpus and dates from around 400 BC. Its author argued against the prevailing view that epilepsy was supernatural in origin and cure, and proposed that dietary therapy had a rational and physical basis.[Note 2] In the same collection, the author of Epidemics describes the case of a man whose epilepsy is cured as quickly as it had appeared, through complete abstinence of food and drink.[Note 3] The royal physician, Erasistratus, declared, "One inclining to epilepsy should be made to fast without mercy and be put on short rations."[Note 4] Galen believed an "attenuating diet"[Note 5] might afford a cure in mild cases and be helpful in others.[8]

The first modern study of fasting as a treatment for epilepsy was in France in 1911.[9] Twenty patients, of all ages, were "detoxified" by consuming a low-calorie vegetarian diet, combined with periods of fasting and purging. Two benefited enormously, but most failed to maintain compliance with the imposed restrictions. The diet improved the patients' mental capabilities, in contrast to their medication, potassium bromide, which dulled the mind.[10]

Around this time, the American exponent of physical culture, Bernarr Macfadden, popularised the use of fasting to restore health. His disciple, the osteopathic physician Hugh Conklin, of Battle Creek, Michigan, began to treat his epilepsy patients by recommending fasting. Conklin conjectured that epileptic seizures were caused when a toxin, secreted from the Peyer's patches in the intestines, was discharged into the bloodstream. He recommended a fast lasting 18 to 25 days to allow this toxin to dissipate. Conklin probably treated hundreds of epilepsy patients with his "water diet" and boasted of a 90% cure rate in children, falling to 50% in adults. Later analysis of Conklin's case records showed 20% of his patients achieved freedom from seizures and 50% had some improvement.[11]

Conklin's fasting therapy was adopted by neurologists in mainstream practice. In 1916, a Dr. McMurray wrote to the New York Medical Journal claiming to have successfully treated epilepsy patients with a fast, followed by a starch- and sugar-free diet, since 1912. In 1921, prominent endocrinologist H. Rawle Geyelin reported his experiences to the American Medical Association convention. He had seen Conklin's success first-hand and had attempted to reproduce the results in 36 of his own patients. He achieved similar results despite only having studied the patients for a short time. Further studies in the 1920s indicated that seizures generally returned after the fast. Charles Howland, the parent of one of Conklin's successful patients and a wealthy New York corporate lawyer, gave his brother John a gift of $5,000 to study "the ketosis of starvation". As professor of paediatrics at Johns Hopkins Hospital, John Howland used the money to fund research undertaken by neurologist Stanley Cobb and his assistant William G. Lennox.[11]

Diet

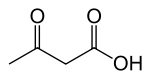

In 1921, Rollin Woodyatt reviewed the research on diet and diabetes. He reported that three water-soluble compounds, β-hydroxybutyrate, acetoacetate and acetone (known collectively as ketone bodies), were produced by the liver in otherwise healthy people when they were starved or if they consumed a very low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet. Russel Wilder, at the Mayo Clinic, built on this research and coined the term ketogenic diet to describe a diet that produced a high level of ketones in the blood (ketonemia) through an excess of fat and lack of carbohydrate. Wilder hoped to obtain the benefits of fasting in a dietary therapy that could be maintained indefinitely. His trial on a few epilepsy patients in 1921 was the first use of the ketogenic diet as a treatment for epilepsy.[11]

Wilder's colleague, paediatrician Mynie Peterman, later formulated the classic diet, with a ratio of one gram of protein per kilogram of body weight in children, 10–15 g of carbohydrate per day, and the remainder of calories from fat. Peterman's work in the 1920s established the techniques for induction and maintenance of the diet. Peterman documented positive effects (improved alertness, behaviour, and sleep) and adverse effects (nausea and vomiting due to excess ketosis). The diet proved to be very successful in children: Peterman reported in 1925 that 95% of 37 young patients had improved seizure control on the diet and 60% became seizure-free. By 1930, the diet had also been studied in 100 teenagers and adults. Clifford Barborka, also from the Mayo Clinic, reported that 56% of those older patients improved on the diet and 12% became seizure-free. Although the adult results are similar to modern studies of children, they did not compare as well to contemporary studies. Barborka concluded that adults were least likely to benefit from the diet, and the use of the ketogenic diet in adults was not studied again until 1999.[11][12]

Anticonvulsants and decline

During the 1920s and 1930s, when the only anticonvulsant drugs were the sedative bromides (discovered 1857) and phenobarbital (1912), the ketogenic diet was widely used and studied. This changed in 1938 when H. Houston Merritt and Tracy Putnam discovered phenytoin (Dilantin), and the focus of research shifted to discovering new drugs. With the introduction of sodium valproate in the 1970s, drugs were available to neurologists that were effective across a broad range of epileptic syndromes and seizure types. The use of the ketogenic diet, by this time restricted to difficult cases such as Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, declined further.[11]

MCT diet

In the 1960s, it was discovered that medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) are much more ketogenic than normal dietary fats (which are mostly long-chain triglycerides). This is because MCTs are absorbed rapidly and contain many calories. The classic ketogenic diet's severe carbohydrate restrictions made it difficult for parents to produce palatable meals that their children would tolerate. In 1971, Peter Huttenlocher devised a ketogenic diet where about 60% of the calories came from the MCT oil, and this allowed more protein and up to three times as much carbohydrate as the classic ketogenic diet. The oil was mixed with at least twice its volume of skimmed milk, chilled, and sipped during the meal or incorporated into food. He tested it on twelve children and adolescents with intractable seizures. Most children improved in both seizure control and alertness, results that were similar to the classic ketogenic diet. Gastrointestinal side effects were a problem, which led one patient to abandon the diet, but meals were easier to prepare and better accepted by the children.[13] The MCT diet replaced the classic ketogenic diet in many hospitals, though some devised diets that were a combination of the two.[11]

Revival

The ketogenic diet achieved national media exposure in the US in October 1994, when NBC's Dateline television programme reported the case of Charlie Abrahams, son of Hollywood producer Jim Abrahams. The two-year-old suffered from epilepsy that had remained uncontrolled by mainstream and alternative therapies. Abrahams discovered a reference to the ketogenic diet in an epilepsy guide for parents and brought Charlie to the Johns Hopkins Hospital, which was one of the few institutions still offering the therapy. Under the diet, Charlie's epilepsy was rapidly controlled and his developmental progress resumed. This inspired Abrahams to create the Charlie Foundation to promote the diet and fund research.[11] A multicentre prospective study began in 1994 and the results were presented to the American Epilepsy Society in 1996. There followed an explosion of scientific interest in the diet. In 1997, Abrahams produced a TV movie, …First Do No Harm, starring Meryl Streep, in which a young boy's intractable epilepsy is successfully treated by the ketogenic diet.[1]

As of 2007, the ketogenic diet is available from around 75 centres in 45 countries. Less restrictive variants, such as the modified Atkins diet, have come into use, particularly among older children and adults. The ketogenic diet is also under investigation for the treatment of a wide variety of disorders other than epilepsy.[1]

Efficacy

The ketogenic diet reduces seizure frequency by 50% in half of the patients who try it and by 90% in a third of patients.[4] Three-quarters of children who respond do so within two weeks, though experts recommend a trial of three months before assuming it has been ineffective.[6] Children with refractory epilepsy are more likely to find the ketogenic diet to be effective than an anticonvulsant drug.[1]

Trial design

Early studies reported high success rates: in one study in 1925, 60% of patients became seizure free, and another 35% of patients had a 50% reduction in seizure frequency. These studies generally examined a cohort of patients recently treated by the physician (known as retrospective studies) and selected patients who had successfully maintained the dietary restrictions. However, these studies are difficult to compare to modern trials. One reason is that these older trials suffered from selection bias, as they excluded patients who were unable to start or maintain the diet and thereby selected from patients who would generate better results. In an attempt to control for this bias, modern study design prefers a prospective cohort (the patients in the study are chosen before therapy begins) in which the results are presented for all patients regardless of whether they started or completed the treatment (known as intent-to-treat analysis).[14]

Another difference between older and newer studies is that the type of patients treated with the ketogenic diet has changed over time. When first developed and used, the ketogenic diet was not a treatment of last resort; in contrast, the children in modern studies have already tried and failed a number of anticonvulsant drugs, so may be assumed to have more difficult-to-treat epilepsy. Early and modern studies also differ because the treatment protocol has changed. In older protocols, the diet was initiated with a prolonged fast, designed to lose 5–10% body weight, and heavily restricted the calorie intake. Concerns over child health and growth led to a relaxation of the diet's restrictions.[14] Fluid restriction was once a feature of the diet, but this led to increased risk of constipation and kidney stones; it is no longer considered beneficial.[4]

Outcomes

The largest modern study with an intent-to-treat prospective design was published in 1998 by a team from the Johns Hopkins Hospital[15] and followed-up by a report published in 2001.[16] As with most studies of the ketogenic diet, there was no control group (patients who were denied the treatment). The study enrolled 150 children. After three months, 83% of them were still on the diet, 26% had experienced a good reduction in seizures, 31% had had an excellent reduction and 3% were seizure-free.[Note 6] At twelve months, 55% were still on the diet, 23% had a good response, 20% had an excellent response and 7% were seizure-free. Those who had discontinued the diet by this stage did so because it was ineffective, too restrictive or due to illness, and most of those who remained were benefiting from it. The percentage of those still on the diet at two, three and four years was 39%, 20% and 12% respectively. During this period the most common reason for discontinuing the diet was because the children had become seizure-free or significantly better. At four years, 16% of the original 150 children had a good reduction in seizure frequency, 14% had an excellent reduction and 13% were seizure-free, though these figures include many who were no longer on the diet. Those remaining on the diet after this duration were typically not seizure-free but had had an excellent response.[16][17]

It is possible to combine the results of several small studies to produce evidence that is stronger than that available from each study alone—a statistical method known as meta-analysis. One of four such analyses, conducted in 2006, looked at 19 studies on a total of 1,084 patients.[18] It concluded that half the patients achieved a 50% reduction in seizures and a third achieved a 90% reduction.[4]

The first randomised controlled trial was published in 2008, which had an intent-to-treat prospective design, but no blinding. This study enrolled 145 children, half of whom were randomly selected to start the ketogenic diet immediately and half to start after a three-month delay. The children who received delayed treatment acted as a control, which is particularly important for medical conditions where patients may get better or worse regardless of treatment. Of the children in the diet group, 38% had at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency, 7% had at least a 90% reduction, and one child became seizure-free. Only 6% of the control group saw a greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency and no children had a 90% reduction. The mean seizure frequency of the diet group fell by a third; the control group's mean seizure frequency actually got worse.[5]

Indications and contra-indications

The ketogenic diet is indicated as an adjunctive (additional) treatment in children with drug-resistant epilepsy.[20][21][22] It is approved by national clinical guidelines in Scotland,[22] England and Wales[20] and reimbursed by nearly all by US insurance companies.[23] Children with a focal lesion (a single point of brain abnormality causing the epilepsy) who would make suitable candidates for surgery are more likely to achieve good results with surgery than with the ketogenic diet.[6] In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence advises that the diet should not be recommended for adults with epilepsy.[20] A minority of epilepsy centres that offer the ketogenic diet also offer a dietary therapy to adults. Some clinicians consider the two less restrictive dietary variants—the low glycemic index treatment and the modified Atkins diet—to be more appropriate for adolescents and adults.[6] Children under six years of age and children who are tube-fed are most likely to comply with the restrictions of the ketogenic diet.[3]

Advocates for the diet recommend that it be seriously considered after two medications have failed, as the chance of other drugs succeeding is only 10%.[6][24][25] The diet can be considered earlier for some epilepsy and genetic syndromes where it has shown particular usefulness. These include Dravet syndrome, infantile spasms, myoclonic-astatic epilepsy and tuberous sclerosis complex.[6]

A survey in 2005 of 88 paediatric neurologists in the US found that 36% regularly prescribed the diet after three or more drugs had failed; 24% occasionally prescribed the diet as a last resort; 24% had only prescribed the diet in a few rare cases; and 16% had never prescribed the diet. There are several possible explanations for this gap between evidence and clinical practice.[26] One major factor may be the lack of adequately trained dietitians, who are needed to administer a ketogenic diet programme.[24]

Because the ketogenic diet radically alters the body's metabolism, it is a first-line therapy in children with certain congenital metabolic diseases. However, it is absolutely contraindicated in others. The diseases Pyruvate dehydrogenase (E1) deficiency and glucose transporter 1 deficiency syndrome prevent the body from using carbohydrates as fuel, which leads to a dependency on ketone bodies. The ketogenic diet is beneficial in treating the seizures and some other symptoms in these diseases.[27] In contrast, the diseases pyruvate carboxylase deficiency, porphyria and other rare genetic disorders of fat metabolism prevent any use of the diet.[6] A person with a disorder of fatty acid oxidation is unable to metabolise fatty acids, which replace carbohydrates as the major energy source on the diet. On the ketogenic diet, their body would consume its own protein stores for fuel, leading to acidosis, and eventually coma and death.[28]

Interactions

The ketogenic diet is usually initiated in combination with the patient's existing drug regime, though these may be discontinued if the diet is successful. There is some evidence of synergistic benefits when the diet is combined with the vagus nerve stimulator or with the drug zonisamide, and that the diet may be less successful in children receiving phenobarbital.[4]

Adverse effects

The ketogenic diet is not a benign, holistic or natural treatment for epilepsy; as with any serious medical therapy, there may be complications. These are generally less severe and less frequent than with anticonvulsant medication or surgery.[23] Common but easily treatable short-term side effects include constipation, low-grade acidosis, and hypoglycaemia if there is an initial fast. Cholesterol may increase by around 30%.[23] Long-term use of the ketogenic diet in children increases the risk of retarded growth, bone fractures, and kidney stones. Supplements are necessary to counter the dietary deficiency in many micronutrients.[4]

About 1 in 20 children on the ketogenic diet will develop kidney stones (compared with 1 in several thousand for the general population). A class of anticonvulsants known as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (topiramate, zonisamide) are known to increase the risk of kidney stones, but the combination of these anticonvulsants and the ketogenic diet does not appear to elevate that risk.[29] The stones are treatable and do not justify discontinuation of the diet.[29] To prevent kidney stones, Johns Hopkins Hospital now gives oral potassium citrate supplements to ketogenic diet patients.[30] However, this empiric usage has not been tested in a prospective controlled trial.[6] Kidney stone formation (nephrolithiasis) occurs on the diet for four reasons.[29]

- Excess calcium in the urine (hypercalciuria) occurs due to increased bone demineralisation with acidosis. Bones are mainly composed of calcium phosphate. The phosphate reacts with the acid, and the calcium is excreted by the kidneys.[29]

- There is an abnormally low concentration of citrate in the urine (hypocitraturia), which normally helps to dissolve free calcium.[29]

- The urine has a low pH, which stops uric acid from dissolving, leading to crystals that act as a nidus for calcium stone formation.[29]

- Many institutions traditionally restricted the water intake of patients on the diet to 80% of normal daily needs;[29] this practice is no longer encouraged.[4]

In adults, common side effects include weight loss, constipation, raised cholesterol levels and, in women, menstrual irregularities including amenorrhoea.[31]

Implementation

The ketogenic diet is a medical nutrition therapy that involves participants from various disciplines. Essential team members include a registered paediatric dietitian who coordinates the diet programme; a paediatric neurologist who is experienced in offering the ketogenic diet; and a registered nurse who is familiar with childhood epilepsy. Additional help may come from a medical social worker who works with the family and a pharmacist who can advise on the carbohydrate content of medicines. Lastly, the parents and other caregivers must be educated in many aspects of the diet in order for it to be safely implemented.[3]

Initiation

The Johns Hopkins Hospital protocol for initiating the ketogenic diet has been widely adopted.[32] It involves a consultation with the patient and their carers and, later, a short hospital admission.[14] Johns Hopkins begins the diet with a short fast, which occasionally poses a significant health risk in young children, so a stay in hospital is necessary to monitor for complications.[33]

At the initial consultation, patients are screened for conditions that may contraindicate the diet. A dietary history is obtained and the parameters of the diet selected: the ketogenic ratio of fat to combined protein and carbohydrate, the calorie requirements, and the fluid intake.[14]

The day before admission to hospital, the proportion of carbohydrate in the diet is decreased and the patient begins fasting after his or her evening meal.[14] On admission, only calorie- and caffeine-free fluids[28] are allowed until dinner, which consists of "eggnog"[Note 7] restricted to one-third of the typical calories for a meal. The following breakfast and lunch are similar, and on the second day, the "eggnog" dinner is increased to two-thirds of a typical meal's caloric content. By the third day, dinner contains the full calorie quota and is a standard ketogenic meal (not "eggnog"). After a ketogenic breakfast on the fourth day, the patient is discharged. If possible, the patient's current medicines are changed to carbohydrate-free formulations.[14]

When in the hospital, glucose levels are checked and the patient is monitored for signs of symptomatic ketosis (which can be treated with a small quantity of orange juice). Lack of energy and lethargy are common but disappear within two weeks.[34] The parents attend classes over the first three full days, which cover nutrition, managing the diet, preparing meals, avoiding sugar and handling illness.[14] The level of parental education and commitment required is much higher than with medication.[35]

Variations on the Johns Hopkins protocol are common. The initiation can be performed using outpatient clinics rather than requiring a stay in hospital. Often, there is no initial fast. Rather than increasing meal sizes over the three-day initiation, some institutions maintain meal size but alter the ketogenic ratio from 2:1 to 4:1.[14]

For patients who benefit, half achieve a seizure reduction within five days (if the diet starts with an initial fast of one to two days), three-quarters achieve a reduction within two weeks, and 90% achieve a reduction within 23 days. If the diet does not begin with a fast, the time for half of the patients to achieve an improvement is longer (two weeks) but the long-term seizure reduction rates are unaffected. Since fasting increases the risk of acidosis and hypoglycaemia, its use is justified only where there is some medical urgency. If no improvement is seen within two months, it is likely that the diet has failed.[35]

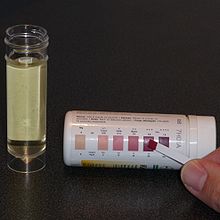

Maintenance

At Johns Hopkins Hospital, outpatient clinics are held at 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months after initiation. A period of minor adjustments is necessary to ensure consistent ketosis is maintained and to better adapt the meal plans to the patient. This fine-tuning is typically done over the telephone with the hospital dietitian[14] and includes changing the number of calories, altering the ketogenic ratio, or adding some MCT or coconut oils to a classic diet.[4] Urinary ketone levels are checked daily to detect whether ketosis has been achieved and to confirm that the patient is following the diet, though the level of ketones does not correlate with an anticonvulsant effect.[14] The test strip contains nitroprusside, which turns from buff-pink to maroon in the presence of acetoacetate (one of the three ketone bodies).[36]

A short-lived increase in seizure frequency may occur during illness or if ketone levels fluctuate. The diet may be modified if seizure frequency remains high, or the child is losing weight.[14] Loss of seizure-control may come from unexpected sources. Even "sugar-free" food can contain carbohydrates such as maltodextrin, sorbitol, starch and fructose. The sorbitol content of suntan lotion and other skincare products may be high enough for some to be absorbed through the skin and thus negate ketosis.[24]

Discontinuation

About 10% of children on the ketogenic diet achieve freedom from seizures, and many are able to reduce or stop taking anticonvulsant drugs. At around two years on the diet, or after six months of being seizure-free, the diet may be gradually discontinued over two or three months. This is done by lowering the ketogenic ratio until urinary ketosis is no longer detected, and then lifting all calorie restrictions.[37]

Children who discontinue the diet after achieving seizure freedom have about a 20% risk of seizures returning. The length of time until recurrence is highly variable but averages two years. This risk of recurrence compares with 10% for resective surgery (where part of the brain is removed) and 30–50% for anticonvulsant therapy. Of those that have a recurrence, just over half can regain freedom from seizures either with anticonvulsants or by returning to the ketogenic diet. Recurrence is more likely if, despite seizure freedom, an EEG shows epileptiform spikes. These spikes are an indication of epileptic activity in the brain, but are below the level that will cause a seizure. Recurrence is also likely if an MRI shows focal abnormalities (for example, children with tuberous sclerosis). Such children may remain on the diet longer than normal, and it has been suggested that children with tuberous sclerosis who achieve seizure freedom could remain on the ketogenic diet indefinitely.[37]

Variants

Classic

The ketogenic diet is calculated by a dietitian for each child. Age, weight, activity levels, culture and food preferences all affect the meal plan. First, the energy requirements are set at 80–90% of the recommended daily amounts (RDA) for the child's age (the high-fat diet requires less energy to process than a typical high-carbohydrate diet). Highly active children or those with muscle spasticity require more calories than this; immobile children require less. The ketogenic ratio of the diet compares the weight of fat to the combined weight of carbohydrate and protein. This is typically 4:1, but children who are under 18 months, who are over 12 years, or who are obese may be started on a 3:1 ratio. Fat is energy-rich, with 9 kcal/g compared to 4 kcal/g for carbohydrate or protein, so portions on the ketogenic diet are smaller than normal. The quantity of fat in the diet can be calculated from the overall energy requirements and the chosen ketogenic ratio. Next, the protein levels are set to allow for growth and body maintenance, and are around 1 g protein for each kg of body weight. Lastly, the amount of carbohydrate is set according to what allowance is left while maintaining the chosen ratio. Any carbohydrate in medications or supplements must be subtracted from this allowance. The total daily amount of fat, protein and carbohydrate is then evenly divided across the meals.[28]

A computer program may be used to help generate recipes. The meals have four components: heavy whipping cream, a protein-rich food (typically meat), a fruit or vegetable, and butter, vegetable oil or mayonnaise. Only low-carbohydrate fruits and vegetables are allowed, which excludes bananas, potatoes, peas, and corn. Suitable fruits are divided into two groups based on the amount of carbohydrate they contain. Vegetables are similarly divided into two groups. Foods within each of these four groups may be freely substituted to allow for variation without needing to recalculate portion sizes. For example, cooked broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower and green beans are all equivalent. Fresh, canned or frozen foods are equivalent, but raw and cooked vegetables differ, and processed foods are an additional complication. Parents are required to be precise when measuring food quantities on an electronic scale accurate to 1 g.[28]

The ketogenic diet is deficient in several vitamins and minerals, so sugar-free supplements are prescribed. The child must eat the whole meal and cannot have extra portions; any snacks must be incorporated into the meal plan. A small amount of MCT oil may be used to help with constipation or to increase ketosis.[28] A typical day of food for a child on a 4:1 ratio, 1,500 calorie ketogenic diet comprises:[23]

- Breakfast: egg with bacon

- 28 g egg, 11 g bacon, 37 g of 36% heavy whipping cream, 23 g butter, 9 g apple.

- Snack: peanut butter ball

- 6 g peanut butter, 9 g butter.

- Lunch: tuna salad

- 28 g tuna fish, 30 g mayonnaise, 10 g celery, 36 g of 36% heavy whipping cream and 15 g lettuce.

- Snack: keto yogurt

- 18 g of 36% heavy whipping cream, 17 g sour cream, 4 g strawberries and artificial sweetener.

- Dinner: cheeseburger

- 22 g minced (ground) beef, 10 g American cheese, 26 g butter, 38 g cream, 10 g lettuce and 11 g green beans.

- Snack: keto custard

- 25 g of 36% heavy whipping cream, 9 g egg and pure vanilla flavouring.

MCT oil

Normal dietary fat contains long-chain triglycerides (LCT). Medium-chain triglycerides are more ketogenic than LCTs because they generate more ketones per calorie of energy when metabolised. Their use allows for a diet with a lower proportion of fat and a greater proportion of protein and carbohydrate,[4] leading to more food choices and larger portion sizes.[2] The original MCT diet developed by Peter Huttenlocher in the 1970s derived 60% of its calories from MCT oil.[13] Consuming that quantity of MCT oil caused abdominal cramps, diarrhoea and vomiting in some children. A figure of 45% is regarded as a balance between achieving good ketosis and minimising gastrointestinal complaints. The classical and modified MCT ketogenic diets are equally effective and differences in tolerability are not statistically significant.[6] The MCT diet is less popular in the United States; MCT oil is more expensive than other dietary fats and is not covered by insurance companies.[4]

Modified Atkins

A modified Atkins diet has been shown, in small, uncontrolled studies, to be effective at reducing seizures in children and adults.[6] The diet consists of 60% fat, 30% protein and 10% carbohydrate by weight. Calories are not restricted. Carbohydrates are limited to 10 g per day for at least one month and may be gradually increased to 10% if this limitation is not tolerated. Consistently strong ketosis is more difficult to achieve than on the ketogenic diet; patients with wildly fluctuating urinary ketones have unfavourable seizure outcomes. Achieving the balance of fat, protein and carbohydrate can be difficult; patients may consume the appetising protein (meat) and leave or vomit the fat. Older children and adolescents who refuse the ketogenic diet's restrictions may tolerate the modified Atkins diet.[38]

Low glycemic index treatment

The low glycemic index treatment (LGIT) is an attempt to achieve the stable blood glucose levels seen in children on the classic ketogenic diet while using a much less restrictive regime.[39] The hypothesis is that stable blood glucose may be one of the mechanisms of action involved in the ketogenic diet,[6] which occurs because the absorption of the limited carbohydrates is slowed by the high fat content.[3] Although it is also a high-fat diet (with approximately 60% calories from fat),[3] the LGIT allows far more carbohydrate than either the classic ketogenic diet or the modified Atkins diet, approximately 40–60 g per day.[4] However, the types of carbohydrates consumed are restricted to those that have a glycemic index lower than 50. The LGIT, as with the modified Atkins diet, has not been studied in large or randomised trials. Despite this, both are offered at most centres that run ketogenic diet programmes, and in some centres they are the primary dietary therapy for adolescents.[6]

Prescribed formulations

Infants and patients fed via a gastrostomy tube can also be given a ketogenic diet. Parents make up a prescribed powdered formula, such as KetoCal, into a liquid feed.[14] Gastrostomy feeding avoids any issues with palatability, and bottle-fed infants readily accept the ketogenic formula.[24] Some studies have found this liquid feed to be more efficacious than a solid ketogenic diet.[4] KetoCal is a nutritionally complete feed containing milk protein and is supplemented with amino acids, fat, carbohydrate, vitamins, minerals and trace elements. It is used to administer the 4:1 ratio classic ketogenic diet in children over one year. Each 100 g of powder contains 73 g fat, 15 g protein and 3 g carbohydrate, and is typically diluted 1:5 with water. The formula is available unflavoured or in an artificially sweetened vanilla flavour and is suitable for tube or sip feeding.[40]

Worldwide

There are theoretically no restrictions on where the ketogenic diet might be used, and it can cost less than modern anticonvulsants. However, fasting and dietary changes are affected by religious and cultural issues. A culture where food is often prepared by grandparents or hired help means more people have to be educated about the diet. When families dine together, sharing the same meal, it can be difficult to separate the child's meal. In many countries, food labelling is not mandatory so calculating the proportions of fat, protein and carbohydrate is difficult. In some countries, it may be hard to find sugar-free forms of medicines and supplements, to purchase an accurate electronic scale, or to afford MCT oils.[41]

In Israel, religious rules prevent mixing meat and milk in one dish. In Asia, the normal diet includes rice and noodles as the main energy source, making their elimination difficult. Therefore the MCT-oil form of the diet, which allows more carbohydrate, has proved useful. In India, religious beliefs commonly affect the diet: some patients are vegetarians or vegans, or will not eat root vegetables, or avoid beef. The Indian ketogenic diet is started without a fast due to cultural opposition towards fasting in children. The low-fat, high-carbohydrate nature of the normal Indian and Asian diet means that their ketogenic diets typically have a lower ketogenic ratio than in America and Europe. However, they appear to be just as effective.[41]

In many developing countries, the ketogenic diet is expensive because dairy fats and meat are dearer than grain, fruit and vegetables. The modified Atkins diet has been proposed as a lower-cost alternative for those countries, with the slightly dearer food bill offset by a reduction in pharmaceutical costs if the diet is successful. The modified Atkins diet is less complex to explain and prepare and requires less support from a dietitian.[42]

Mechanism of action

Seizure pathology

The brain is composed of a network of neurons that transmit signals by propagating nerve impulses. The propagation of this impulse from one neuron's synapse to another is typically controlled by neurotransmitters, though there are also electrical pathways between some neurons. Neurotransmitters can inhibit impulse firing (primarily done by γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)) or they can excite the neuron into firing (primarily done by glutamate). A neuron that releases inhibitory neurotransmitters from its terminals is called an inhibitory neuron, while one that releases excitatory neurotransmitters is an excitatory neuron. When the normal balance between inhibition and excitation is significantly disrupted in all or part of the brain, a seizure can occur. The GABA system is an important target for anticonvulsant drugs, since seizures may be discouraged by increasing GABA synthesis, decreasing its breakdown, or enhancing its effect on neurons.[7]

The nerve impulse is characterised by a great influx of sodium ions through channels in the neuron's cell membrane followed by an efflux of potassium ions through other channels. The neuron is unable to fire again for a short time (known as the refractory period), which is mediated by another potassium channel. The flow through these ion channels is governed by a "gate" which is opened by either a voltage change or a chemical messenger known as a ligand (such as a neurotransmitter). These channels are another target for anticonvulsant drugs.[7]

There are many ways in which epilepsy occurs. Examples of pathological physiology include: unusual excitatory connections within the neuronal network of the brain; abnormal neuron structure leading to altered current flow; decreased inhibitory neurotransmitter synthesis; ineffective receptors for inhibitory neurotransmitters; insufficient breakdown of excitatory neurotransmitters leading to excess; immature synapse development; and impaired function of ionic channels.[7]

Seizure control

Although many hypotheses have been put forward to explain how the ketogenic diet works, it remains a mystery. Disproven hypotheses include systemic acidosis (high levels of acid in the blood), electrolyte changes and hypoglycaemia (low blood glucose).[14] Although many biochemical changes are known to occur in the brain of a patient on the ketogenic diet, it is not known which of these has an anticonvulsant effect. The lack of understanding in this area is similar to the situation with many anticonvulsant drugs.[43]

On the ketogenic diet, carbohydrates are severely restricted and so cannot provide for all the metabolic needs of the body. Instead, fatty acids are used as the major source of fuel. These are used through fatty-acid oxidation in the cell's mitochondria (the energy-producing part of the cell). Humans can convert some amino acids into glucose by a process called gluconeogenesis, but cannot do this for fatty acids.[44] Since amino acids are needed to make proteins, which are essential for growth and repair of body tissues, these cannot be used only to produce glucose. This could pose a problem for the brain, since it is normally fuelled solely by glucose, and fatty acids do not cross the blood-brain barrier. Fortunately, the liver can use fatty acids to synthesise the three ketone bodies β-hydroxybutyrate, acetoacetate and acetone. These ketone bodies enter the brain and substitute for glucose.[43]

The ketone bodies are possibly anticonvulsant in themselves; in animal models, acetoacetate and acetone protect against seizures. The ketogenic diet results in adaptive changes to brain energy metabolism that increase the energy reserves; ketone bodies are a more efficient fuel than glucose, and the number of mitochondria is increased. This may help the neurons to remain stable in the face of increased energy demand during a seizure, and may confer a neuroprotective effect.[43]

The ketogenic diet has been studied in at least 14 rodent animal models of seizures. It is protective in many of these models and has a different protection profile than any known anticonvulsant. This, together with studies showing its efficacy in patients who have failed to achieve seizure control on half a dozen drugs, suggests a unique mechanism of action.[43]

Anticonvulsants suppress epileptic seizures, but they neither cure nor prevent the development of seizure susceptibility. The development of epilepsy (epileptogenesis) is a process that is poorly understood. A few anticonvulsants (valproate, levetiracetam and benzodiazepines) have shown antiepileptogenic properties in animal models of epileptogenesis. However, no anticonvulsant has ever achieved this in a clinical trial in humans. The ketogenic diet has been found to have antiepileptogenic properties in rats.[43]

Other applications

The ketogenic diet may be a successful treatment for several rare metabolic diseases. Case reports of two children indicate that it may be a possible treatment for astrocytomas, a type of brain tumour. Autism, depression, migraine headaches, polycystic ovary syndrome, and type 2 diabetes mellitus have also been shown to improve in small case studies. There is evidence from uncontrolled clinical trials and studies in animal models that the ketogenic diet can provide symptomatic and disease-modifying activity in a broad range of neurodegenerative disorders including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease,[14] and may be protective in traumatic brain injury and stroke.[45] Because tumour cells are inefficient in processing ketone bodies for energy, the ketogenic diet has also been suggested as a treatment for cancer.[46] As of 2008[update], there is insufficient evidence to support the use of the ketogenic diet as a treatment for these conditions.[6]

Notes

- ^ Unless otherwise stated, the term fasting in this article refers to going without food while maintaining calorie-free fluid intake.

- ^ Hippocrates, On the Sacred Disease, ch. 18; vol. 6.

- ^ Hippocrates, Epidemics, VII, 46; vol. 5.

- ^ Galen, De venae sect. adv. Erasistrateos Romae degentes, c. 8; vol. 11.

- ^ Galen, De victu attenuante, c. 1.

- ^ A good reduction is defined here to mean a 50–90% decrease in seizure frequency. An excellent reduction is a 90–99% decrease.

- ^ Ketogenic "eggnog" is used during induction and is a drink with the required ketogenic ratio. For example, a 4:1 ratio eggnog would contain 60 g of 36% heavy whipping cream, 25 g pasteurised raw egg, vanilla and saccharin flavour. This contains 245 calories, 4 g protein, 2 g carbohydrate and 24 g fat (24:6 = 4:1).[34] The eggnog may also be cooked to make a custard, or frozen to make ice cream.[28]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Freeman JM, Kossoff EH, Hartman AL. The ketogenic diet: one decade later. Pediatrics. 2007 Mar;119(3):535–43. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2447. [PMID 17332207]

- ^ a b Liu YM. Medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) ketogenic therapy. Epilepsia. 2008 Nov;49 Suppl 8:33-6. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01830.x. [PMID 19049583]

- ^ a b c d e Zupec-Kania BA, Spellman E. An overview of the ketogenic diet for pediatric epilepsy. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008 Dec–2009 Jan;23(6):589–96. doi:10.1177/0884533608326138. [PMID 19033218]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Kossoff EH, Zupec-Kania BA, Rho JM. Ketogenic diets: an update for child neurologists. J Child Neurol. 2009 Aug;24(8):979–88. doi:10.1177/0883073809337162. [PMID 19535814]

- ^ a b Neal EG, Chaffe H, Schwartz RH, Lawson MS, Edwards N, Fitzsimmons G, et al. The ketogenic diet for the treatment of childhood epilepsy: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008 Jun;7(6):500–6. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70092-9. [PMID 18456557]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kossoff EH, Zupec-Kania BA, Amark PE, Ballaban-Gil KR, Bergqvist AG, Blackford R, et al. Optimal clinical management of children receiving the ketogenic diet: recommendations of the International Ketogenic Diet Study Group. Epilepsia. 2009 Feb;50(2):304-17. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01765.x. [PMID 18823325]

- ^ a b c d Stafstrom CE. An introduction to seizures and epilepsy. In: Stafstrom CE, Rho JM, editors. Epilepsy and the ketogenic diet. Totowa: Humana Press; 2004. ISBN 1588292959.

- ^ Temkin O. The falling sickness: a history of epilepsy from the Greeks to the beginnings of modern neurology. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1971. p. 33, 57, 66, 67, 71, 78. ISBN 0801848490.

- ^ Guelpa G, Marie A. La lutte contre l'epilepsie par la desintoxication et par la reeducation alimentaire. Rev Ther med-Chirurg. 1911; 78: 8–13. As cited by Bailey (2005).

- ^ Bailey EE, Pfeifer HH, Thiele EA. The use of diet in the treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2005 Feb;6(1):4–8. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.10.006. [PMID 15652725]

- ^ a b c d e f g Wheless JW. History and origin of the ketogenic diet (PDF). In: Stafstrom CE, Rho JM, editors. Epilepsy and the ketogenic diet. Totowa: Humana Press; 2004. ISBN 1588292959.

- ^ Kossoff EH. Do ketogenic diets work for adults with epilepsy? Yes! epilepsy.com. 2007, March. Cited 24 October 2009.

- ^ a b Huttenlocher PR, Wilbourn AJ, Signore JM. Medium-chain triglycerides as a therapy for intractable childhood epilepsy. Neurology. 1971 Nov;21(11):1097–103. [PMID 5166216]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Hartman AL, Vining EP. Clinical aspects of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia. 2007 Jan;48(1):31–42. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.00914.x [PMID 17241206]

- ^ Freeman JM, Vining EP, Pillas DJ, Pyzik PL, Casey JC, Kelly LM. The efficacy of the ketogenic diet—1998: a prospective evaluation of intervention in 150 children. Pediatrics. 1998 Dec;102(6):1358–63. [PMID 9832569]. Lay summary—JHMI Office of Communications and Public Affairs. Updated 7 December 1998. Cited 6 March 2008.

- ^ a b Hemingway C, Freeman JM, Pillas DJ, Pyzik PL. The ketogenic diet: a 3- to 6-year follow-up of 150 children enrolled prospectively. Pediatrics. 2001 Oct;108(4):898–905. [PMID 11581442].

- ^ Kossoff EH, Rho JM. Ketogenic diets: evidence for short- and long-term efficacy. Neurotherapeutics. 2009 Apr;6(2):406–14. doi:10.1016/j.nurt.2009.01.005 [PMID 19332337].

- ^ Henderson CB, Filloux FM, Alder SC, Lyon JL, Caplin DA. Efficacy of the ketogenic diet as a treatment option for epilepsy: meta-analysis. J Child Neurol. 2006 Mar;21(3):193-8. doi:10.2310/7010.2006.00044. [PMID 16901419]

- ^ Bergqvist AGC. Indications and Contraindications of the Ketogenic diet. In: Stafstrom CE, Rho JM, editors. Epilepsy and the ketogenic diet. Totowa: Humana Press; 2004. p. 53–61. ISBN 1588292959.

- ^ a b c Stokes T, Shaw EJ, Juarez-Garcia A, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Baker R. The diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care. (PDF). London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2004. ISBN 1842578081.

- ^ Levy R, Cooper P. Ketogenic diet for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(3):CD001903. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001903 [PMID 12917915]

- ^ a b Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Guideline 81, Diagnosis and management of epilepsies in children and young people. A national clinical guideline (PDF). Edinburgh: Royal College of Physicians; 2005. ISBN 1899893245.

- ^ a b c d Turner Z, Kossoff EH. The ketogenic and Atkins diets: recipes for seizure control (PDF). Pract Gastroenterol. 2006 Jun;29(6):53, 56, 58, 61–2, 64.

- ^ a b c d Kossoff EH, Freeman JM. The ketogenic diet—the physician's perspective. In: Stafstrom CE, Rho JM, editors. Epilepsy and the ketogenic diet. Totowa: Humana Press; 2004. p. 53–61. ISBN 1588292959.

- ^ Spendiff S. The diet that can treat epilepsy. Guardian. 2008 Aug 15;Sect. Health & wellbeing.

- ^ Mastriani KS, Williams VC, Hulsey TC, Wheless JW, Maria BL. Evidence-based versus reported epilepsy management practices. J Child Neurol. 2008 Feb 15. doi:10.1177/0883073807309785. [PMID 18281618]

- ^ Huffman J, Kossoff EH. State of the ketogenic diet(s) in epilepsy (PDF). Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006 Jul;6(4):332–40. [PMID 16822355]

- ^ a b c d e f Zupec-Kania B, Werner RR, Zupanc ML. Clinical Use of the Ketogenic Diet—The Dietitian's Role. In: Stafstrom CE, Rho JM, editors. Epilepsy and the ketogenic diet. Totowa: Humana Press; 2004. p. 63–81. ISBN 1588292959.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sampath A, Kossoff EH, Furth SL, Pyzik PL, Vining EP. Kidney stones and the ketogenic diet: risk factors and prevention (PDF). J Child Neurol. 2007 Apr;22(4):375–8. doi:10.1177/0883073807301926. [PMID 17621514]

- ^ Muzykewicz DA, Lyczkowski DA, Memon N, Conant KD, Pfeifer HH, Thiele EA. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of the low glycemic index treatment in pediatric epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009 May;50(5):1118–26. [PMID 19220406]

- ^ Kossoff E. Is there a role for the ketogenic diet beyond childhood? In: Freeman J, Veggiotti P, Lanzi G, Tagliabue A, Perucca E. The ketogenic diet: from molecular mechanisms to clinical effects. Epilepsy Res. 2006 Feb;68(2):145–80. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.10.003. [PMID 16523530]

- ^ Kim DY, Rho JM. The ketogenic diet and epilepsy. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008 Mar;11(2):113–120. doi:10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f44c06. [PMID 18301085]

- ^ Bergqvist AG, Schall JI, Gallagher PR, Cnaan A, Stallings VA. Fasting versus gradual initiation of the ketogenic diet: a prospective, randomized clinical trial of efficacy. Epilepsia. 2005 Nov;46(11):1810–9. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00282.x. [PMID 16302862]

- ^ a b Vining EP, Freeman JM, Ballaban-Gil K, Camfield CS, Camfield PR, Holmes GL, et al. A multicenter study of the efficacy of the ketogenic diet. Arch Neurol. 1998 Nov;55(11):1433–7. [PMID 9823827]

- ^ a b Kossoff EH, Laux LC, Blackford R, Morrison PF, Pyzik PL, Hamdy RM, et al. When do seizures usually improve with the ketogenic diet? (PDF). Epilepsia. 2008 Feb;49(2):329–33. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01417.x. [PMID 18028405]

- ^ Musa-Veloso K, Cunnane SC. Measuring and interpreting ketosis and fatty acid profiles in patients on a high-fat ketogenic diet. In: Stafstrom CE, Rho JM, editors. Epilepsy and the ketogenic diet. Totowa: Humana Press; 2004. p. 129–41. ISBN 1588292959.

- ^ a b Martinez CC, Pyzik PL, Kossoff EH. Discontinuing the ketogenic diet in seizure-free children: recurrence and risk factors. Epilepsia. 2007 Jan;48(1):187–90. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00911.x. [PMID 17241227]

- ^ Kang HC, Lee HS, You SJ, Kang du C, Ko TS, Kim HD. Use of a modified Atkins diet in intractable childhood epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007 Jan;48(1):182–6. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00910.x. [PMID 17241226]

- ^ Pfeifer HH, Thiele EA. Low-glycemic-index treatment: a liberalized ketogenic diet for treatment of intractable epilepsy. Neurology 2005 Dec 13;65(11):1810-2. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000187071.24292.9e. [PMID 16344529]

- ^ KetoCal. SHS International. Updated 2007. Cited 11 October 2009.

- ^ a b Kossoff EH, McGrogan JR. Worldwide use of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia. 2005 Feb;46(2):280–9. doi:10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.42704.x. [PMID 15679509]

- ^ Kossoff EH, Dorward JL, Molinero MR, Holden KR. The modified Atkins diet: a potential treatment for developing countries. Epilepsia. 2008 Sep;49(9):1646-7. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01580_6.x [PMID 18782218]

- ^ a b c d e Hartman AL, Gasior M, Vining EP, Rogawski MA. The neuropharmacology of the ketogenic diet. Pediatr Neurol. 2007 May;36(5):281–292. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.02.008. [PMID 17509459]

- ^ Kerndt PR, Naughton JL, Driscoll CE, Loxterkamp DA. Fasting: the history, pathophysiology and complications. West J Med. 1982 Nov;137(5):379–99. [PMID 6758355]

- ^ Gasior M, Rogawski MA, Hartman AL. Neuroprotective and disease-modifying effects of the ketogenic diet. Behav Pharmacol. 2006;17(5–6):431–9. [PMID 16940764]

- ^ Barañano KW, Hartman AL.The ketogenic diet: uses in epilepsy and other neurologic illnesses. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2008;10(6):410-9. [PMID 18990309]

Further reading

- Freeman JM, Kossoff EH, Freeman JB, Kelly MT. The Ketogenic Diet: A Treatment for Children and Others with Epilepsy. 4th ed. New York: Demos; 2007. ISBN 1932603182.

External links

- Matthew's Friends. A UK charity and information resource.

- The Charlie Foundation. A US charity and information resource, set up by Jim Abrahams.

- epilepsy.com: Dietary Therapies & Ketogenic News. Information and regular research news updates.

- A Talk with John Freeman: Tending the Flame. An interview discussing the ketogenic diet that appeared in BrainWaves, Fall 2003, Volume 16, Number 2.