The Great Escape (film)

| The Great Escape | |

|---|---|

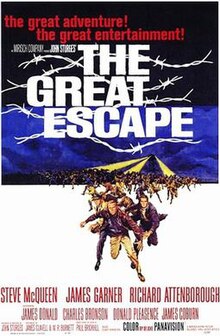

original movie poster by Frank McCarthy | |

| Directed by | John Sturges |

| Written by | Novel: Paul Brickhill Screenplay: James Clavell W.R. Burnett Walter Newman (uncredited) |

| Screenplay by | James Clavell |

| Produced by | John Sturges |

| Starring | Steve McQueen James Garner Richard Attenborough |

| Cinematography | Daniel L. Fapp |

| Edited by | Ferris Webster |

| Music by | Elmer Bernstein |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date | 4 July Template:Fy |

Running time | 172 minutes |

| Country | Template:FilmUS |

| Language | Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{lang-en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. |

| Budget | $4,000,000 |

| Box office | $5,500,000 (US) |

The Great Escape is a Template:Fy film about an escape by Allied prisoners of war from a German POW camp during World War II. It is based on the book The Great Escape by Paul Brickhill, which is a novelization of the true story of a mass escape from Stalag Luft III. The film was made by the Mirisch Corporation, released by United Artists, produced and directed by John Sturges, and stars Steve McQueen, James Garner, and Richard Attenborough.

Plot

Having wasted an enormous amount of resources on recapturing escaped Allied prisoners of war (POWs), German forces move the most determined and capable escapees to a new, high-security prisoner of war camp. The commandant, Luftwaffe Colonel von Luger, tells the Senior British Officer (SBO) Group Captain Ramsey, "There will be no escapes from this camp." The SBO replies that it is their duty to try to escape. After several failed escape attempts on the first day, the POWs settle into the prison camp.

Gestapo and SS agents bring Squadron Leader Roger Bartlett (RAF) to the camp and deliver him to von Luger. Gestapo agent Kuhn suggests that Bartlett be kept under the strictest security confinement permanently, because they believe he is the leader of numerous escape attempts. As Kuhn leaves, he warns Bartlett that if he escapes again and is caught, he will be shot. Afterwards, Bartlett is put with the rest of the POWs.

Locked up with "every escape artist in Germany", and well known by them as "Big X", Bartlett recognizes the opportunity and immediately plans the greatest escape attempted—a tunnel system for exfiltrating 250 prisoners. The intent is to "confuse and harass the enemy" to the point that as many troops and resources as possible will be wasted on finding and detaining POWs, instead of being used on the front line.

Teams are organized to tunnel, make civilian clothing, forge documents, procure contraband materials, and prevent the guards from discovering their work. Flight Lieutenant Hendley, an American in the RAF, is "the scrounger" who finds ingenious ways to get what the others need, from a camera to identity cards. Australian Flying Officer Louis Sedgwick, "the manufacturer", makes many of the tools, such as picks for digging and bellows for pumping air into the tunnels. Flight Lieutenant Danny Velinski and William "Willie" Dickes are "the tunnel kings", and are in charge of making the tunnels. Forgery is handled by Flight Lieutenant Colin Blythe, who becomes nearly blind from intricate work by candlelight; Hendley takes it upon himself to be Blythe's guide in the escape.

The prisoners work on three tunnels simultaneously, codenamed "Tom", "Dick", and "Harry". Work on Harry and Dick is stopped so that more work can be performed on Tom. The worst of the work noise is covered by the prisoner choir led by Flight Lieutenant Cavendish, while dirt from the tunnels is concealed by POWs who carry excavated soil in their trousers to the camp's gardens.

Meanwhile, USAAF Captain Virgil Hilts, "The Cooler King", irritates the guards with frequent escape attempts and irreverent behavior. His first attempt, conceived while in the cooler, is a short tunnel with RAF Flying Officer Archibald Ives; they are caught and returned to the cooler.

While the mostly British POWs are enjoying a 4th of July celebration, organized by the three Americans in the camp, the guards discover tunnel Tom. The mood drops to agonizing disappointment, and hits Ives the hardest. He is impulsively drawn to the barbed wire fence that confines them in the camp and climbs it in desperation, in full view of the tower guards. Hilts runs to stop him but is too late, and Ives is machine-gunned dead near the top of the fence. With Tom discovered, the prisoners switch their efforts to Harry.

After the death of Ives, Hilts' escape partner, Hilts agrees to a previous request made by Bartlett, to change his escape plan and reconnoiter in the vicinity outside the POW camp and then allow himself to be recaptured. The information Hilts brings back is used by POW cartographers to create maps of the area, including the nearest town and railway station.

The last part of the tunnel is completed on the night of the escape, but is 20 feet short of woods that are to provide cover. Danny nearly snaps from claustrophobia in the tunnel and delays those behind him, but is helped by Willie. Seventy-six escape before the guards discover the escaping prisoners.

After attempts to reach neutral Switzerland, Sweden, and Spain, almost all the POWs are recaptured or killed. Hendley and Blythe steal an airplane, intending to fly over the Swiss border, but the engine fails and they crash-land. Soldiers arrive on the road a distance away. Unknowingly, the blind Blythe stands in their view and when he turns away, he is shot. Hendley comes to his friend's aid, waving his hands and shouting "don't shoot", and is captured as Blythe dies. Flt. Lt. Cavendish, having hitched a ride in a truck, is captured at a checkpoint, discovering another POW, Haynes, captured in his German soldier disguise.

Bartlett is recognized at a distance in a crowded railroad station by Gestapo agent Kuhn. Another escapee, Ashley-Pitt, sees this and sacrifices himself when he kills Kuhn with his own gun, and soldiers then shoot and kill him. In the commotion, Bartlett and MacDonald are able to slip away, but they are caught later. Lastly, Hilts steals a motorcycle, is pursued by German soldiers, jumps a barbed wire fence with the motorcycle to get away, but becomes entangled in another barbed wire fence and is captured.

Three truckloads of captured POWs go down a country road and split off in three separate directions. One of the trucks, containing Bartlett, MacDonald, Cavendish, and others, is shown to stop in a field and the POWs are told to get out and "stretch their legs". They are then shot dead with a machine gun. In total, 50 escapees are executed. Meanwhile, Hendley and nine others are returned to the POW camp. Von Luger is relieved of command and driven away by the SS to face the consequences of failing to prevent the breakout.

Only three escapees evade capture and make it to safety. Danny and Willie steal a rowboat and proceed downriver to the Baltic coast, where they board a Swedish merchant ship. Sedgewick steals a bicycle, then rides hidden in a freight train boxcar to France, where he is then guided by the Resistance to Spain.

Hilts is brought back alone to the camp, and taken to the cooler. A fellow POW gets Hilts' baseball and glove and throws it to him when Hilts and his guards pass by. The guard locks him in his cell and walks away, but momentarily pauses when he hears the familiar sound of Hilts bouncing his baseball against a cell wall. The film ends with this scene, under the caption, "This picture is dedicated to the fifty."

Cast

| Actor | Role |

|---|---|

| Steve McQueen | Captain Virgil Hilts USAAF, "The Cooler King" |

| James Garner | Flight Lieutenant Bob Hendley DFC RAF, "The Scrounger" |

| Richard Attenborough | Squadron Leader Roger Bartlett DFC RAF, "Big X" |

| James Donald | Group Captain Ramsey DSO MC RAF, "The SBO [Senior British Officer]" |

| Charles Bronson | Flight Lieutenant Danny Velinski DFC RAF, "The Tunnel King" |

| Donald Pleasence | Flight Lieutenant Colin Blythe RAF, "The Forger" |

| James Coburn | Flying Officer Sedgwick RAAF, "The Manufacturer" |

| Hannes Messemer | Oberst von Luger, "The Kommandant" |

| David McCallum | Lieutenant-Commander Eric Ashley-Pitt RN, "Dispersal" |

| Gordon Jackson | Flight Lieutenant 'Mac' MacDonald RAF, "Intelligence" |

| John Leyton | Flight Lieutenant William 'Willie' Dickes RAF, "The Tunneler" |

| Angus Lennie | Flying Officer Archibald 'Archie' Ives RAF, "The Mole" |

| Nigel Stock | Flight Lieutenant Denys Cavendish RAF, "The Surveyor" |

| Robert Graf | Werner, "The Ferret" |

| Jud Taylor | First Lieutenant Goff USAAF |

| Hans Reisser | Kuhn, Gestapo |

| Harry Riebauer | Oberfeldwebel Stratwitch, "The Security Sergeant" |

| William Russell | Flight Lieutenant Sorren RAF, "Security" |

| Robert Freytag | Hauptmann Posen, "The Adjutant" |

| Ulrich Beiger | Preissen, Gestapo |

| George Mikell | SS-Obersturmführer Dietrich |

| Lawrence Montaigne | Flying Officer Haynes RCAF, "Diversions" |

| Robert Desmond | Flying Officer 'Griff' Griffith RAF, "The Tailor" |

| Til Kiwe | Frick, "The Ferret" |

| Heinz Weiss | Kramer, "The Ferret" |

| Tom Adams | Flight Lieutenant 'Dai' Nimmo RAF, "Diversions" |

| Karl-Otto Alberty | SS-Obersturmführer Steinach |

Production

Adaptation

The story was adapted for the screen by James Clavell, W.R. Burnett, and Walter Newman from Paul Brickhill's book The Great Escape. Brickhill had been a prisoner at Stalag Luft III during World War II and novelized the experience.

The screenwriters increased the importance of the roles of American POWs relative to the reality of the actual escape, as their role was minor and it was a largely British affair.[1] Some fictional, dramatic elements were added, such as Hilts's dash for the border by motorcycle. The scene was added at the request of McQueen, who did nearly all the stunt riding himself except for the jump,[2] and has become one of the most famous action scenes of 1960s cinema.

Ex-POWs asked the filmmakers to exclude details about the help that the POWs received from their home countries, such as maps, papers and tools hidden in gift packages, lest it jeopardize future POW escapes. The filmmakers complied.[3]

Casting

Steve McQueen's Virgil Hilts, "remains one of the film's most enduring characters, his cooler king having become an icon of cool who continues to inform popular culture."[citation needed] Critic Leonard Maltin wrote that "the large, international cast is superb, but the standout is McQueen; it's easy to see why this cemented his status as a superstar."[4]

Richard Attenborough was cast as Sqn. Ldr. Roger Bartlett RAF ("Big X"), a character based on Roger Bushell, a South Africa born British POW at Stalag Luft III.[5] Similarly, the character of Flt. Lt. Colin Blythe RAF ("The Forger") was created, based on Tim Walenn, and played by Donald Pleasence.[6]

Donald Pleasence had served in the Royal Air Force during World War II. He was shot down and spent a year in a German prisoner-of-war camp Stalag Luft 1. James Garner was a soldier and wounded twice during the Korean War and was a scrounger during that time.[7]

Hannes Messemer was cast as the Kommandant of Stalag Luft III, "Colonel von Luger," a character based on Oberst Friedrich Wilhelm von Lindeiner-Wildau.[8]

Angus Lennie's Flying Officer Archibald Ives RAF "The Mole" was based on Jimmy Kiddel who was shot dead while trying to scale the perimeter fence.[9]

Location and set design

The "barbed wire" that Hilts crashed into before being recaptured was actually made of little strips of rubber tied around normal wire, and was made by the cast and crew during their free time.[10] The film depicts Tom's entrance as being under a stove and Harry's as in a drain sump in a washroom. In reality, Dick's entrance was the drain sump, Harry's was under the stove, and Tom's was in a darkened corner next to a stove chimney.[11]

Reception

The Great Escape did not command much respect until years after its release. Its audience has broadened, prompting film historians to reappraise its unique qualities.[12]

Upon its theatrical release in 1963, New York Times critic Bosley Crowther wrote: "But for much longer than is artful or essential, The Great Escape grinds out its tormenting story without a peek beneath the surface of any man, without a real sense of human involvement. It's a strictly mechanical adventure with make-believe men."[13] British film critic Leslie Halliwell described it as "pretty good but overlong POW adventure with a tragic ending".[14] In Time magazine 1963: "The use of color photography is unnecessary and jarring, but little else is wrong with this film. With accurate casting, a swift screenplay, and authentic German settings, Producer-Director John Sturges has created classic cinema of action. There is no sermonizing, no soul probing, no sex. The Great Escape is simply great escapism".[15]

The film has been regularly shown on British TV, especially during holiday periods such as Christmas.[16] In a 2006 poll in the UK, regarding the family movie that TV viewers would most want to see on Christmas Day, The Great Escape came in third, and was first among the choices of male viewers.[17]

In 2009 a group of seven former POWs returned to Stalag Luft III to mark the 65th anniversary of the real escape,[18] which included a viewing of the film. According to the veterans, the first half depicting life in the camp is authentic; for example, the machinegunning of a man who snaps and tries to scale the fence, and the way the tunnels were dug. However, one veteran criticised McQueen for glamorising the situation.[19]

In Popular Culture

References to scenes and motifs from the film, as well as Elmer Bernstein's iconic musical theme, have frequently appeared in other films, television series, advertisements, and even as a mobile phone ringtone. These include television shows Monty Python's Flying Circus, The Simpsons, Hogan's Heroes, Nash Bridges, Seinfeld, Get Smart, Red Dwarf, as well as the films Chicken Run, Reservoir Dogs, The Parent Trap, and Charlie's Angels.[20]

TV sequel and video games

A highly fictionalized, made-for-television sequel, The Great Escape II: The Untold Story, appeared many years later. It starred Christopher Reeve with Donald Pleasence as an SS villain.[21]

Several video games were based on the movie, including one in 1986, and one in 2003.[citation needed]

See also

- Stalag Luft III, and its section The "Great Escape", which covers the real escape.

References

- ^ Wolter, Tim (2001). POW baseball in World War II. McFarland. pp. 24–5. ISBN 978-0786411863.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Davis, Rob. "The 1963 film of the Great Escape". History of Film. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- ^ The Great Escape: Heroes Underground documentary, available on The Great Escape DVD Special Edition.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (1999). Leonard Maltin's Family Film Guide. New York: Signet. p. 225. ISBN 0-451-19714-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Whalley, Kirsty (2008-11-10). "Escape artist's inspiring exploits". This is Local London. Newsquest Media Group / A Gannett Company. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Now sporting a huge, bushy moustache ... he set to work arranging the operations of the forgery department" (Vance 2003, p. 44)

- ^ DVD extra

- ^ Carroll, Tim (2004). The Great Escapers. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 1-84018-904-5.

- ^ Hall, Allan (2009-03-24). "British veterans mark Great Escape anniversary". Telegraph.co.uk. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Retrieved 2009-10-26.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Archived version 2009-10-26 - ^ Rufford, Nick (2009-02-13). "Video: The Great Escape, re-enacted". Times Online. Times Newspapers Ltd. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) See 4th paragraph. Archived version 2009-10-20 - ^ (Vance 2003, p. 116-118)

- ^ Eder, Bruce (2009). "allmovie - Review: The Great Escape". AllMovie. Macrovision Corporation. Retrieved 2009-10-14.

- ^ Bosley Crowther (1963-08-08). "P.O.W.'s in 'Great Escape':Inmates of Nazi Camp Are Stereotypical – Steve McQueen Leads Snarling Tunnelers". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Walker, John (1997). Halliwell's film and Video Guide. London: HarperCollins. p. 311. ISBN 006387799.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ "Cinema: The Getaway". Time. Time Inc. 1963-07-19. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ^ Empire - Special Collectors' Edition - The Greatest Action Movies Ever, published in 2001

- ^ "TV classics are recipe for Christmas Day delight". Freeview. 2006-12-11. Retrieved 2009-09-05. Archived version 2009-09-05

- ^ "Veterans of the Great Escape visit old stalag" article at The Independent website

- ^ [http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/article5970344.ece "'Great Escape' PoWs remember comrades... and boo 'silly' Steve McQueen, The Times

- ^ Nixon, Rob (2008). "Pop Culture 101: The Great Escape". Turner Classic Movies, A Time Warner Company.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0095252/

Bibliography

- The Great Escape, Paul Brickhill.

- The Tunnel King, The True Story of Wally Floody & the Great Escape, Barbara Hehner. Publ.: Harper Trophy Canada 2004.

- The Longest Tunnel, Alan Burgess.

- "Tre kom tilbake" (Three returned)", the Norwegian book by surviving escapee Jens Müller. Publ.: Gyldendal 1946.

- Exemplary Justice, Allen Andrews. Details the manhunt by the Royal Air Force's special investigations unit after the war to find and bring to trial the perpetrators of the "Sagan murders".

- Project Lessons from the Great Escape (Stalag Luft III), Mark Kozak-Holland. The prisoners formally structured their work as a project. This book analyzes their efforts using modern project management methods.

- 'Wings' Day, Sydney Smith, story of Wing Commander Harry "Wings" Day Pan Books 1968 ISBN 0330024949

External links

- The Great Escape at IMDb

- The Great Escape at the TCM Movie Database

- The Great Escape at AllMovie

- The Real Great Escape

- Great Escape (PBS Nova)

- Detailed information about the real event

- Exhibition about this and other escapes at the Imperial War Museum, London (until 31 July 2006)

- First hand account of Stalag Luft III by Wing Commander Ken Rees

- Pivotal Games site for the computer game version of The Great Escape

- World of Spectrum entry for the 1986 video game

- Project Management lessons from the Great Escape

- Interactive map of Tunnel Harry

- James Garner Interview on the Charlie Rose Show

- James Garner interview at Archive of American Television

- Death of Eric Dowling, one of the escape planners [dead link]

- Death of Alex Lees, who helped with construction of tunnel 'Harry'