Laffer curve

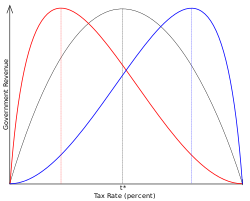

The Laffer curve is a thought experiment which compares total tax revenue against the rate of taxation. It is based on the hypothesis that changes in the rate of taxation impact the incentive to earn taxable income. At the ends of the Laffer curve, both a 0% income tax rate and a 100% tax rate generate no revenue, thus a revenue maximising taxation rate lies somewhere in between. It is clear that a 0% tax rate raises no revenue, but the hypothesis is that a 100% tax rate will also generate no revenue because at such a rate there is no longer any incentive for a rational taxpayer to earn any income. Thus the revenue raised will be 100% of nothing. One potential outcome of the experiment is that increasing taxes beyond a certain point will become counterproductive for raising tax revenue because of diminishing returns. The Laffer curve is central to supply side economics, where the curve's use in debates over rates of taxation has been the subject of controversy.

The Laffer curve was popularised by Arthur Laffer in the 1980s. However, the idea dates to the 14th century North African polymath Ibn Khaldun, who discusses the idea in his 1377 Muqaddimah. More recently, in his 1936 General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, John Maynard Keynes described how past a certain point, increasing taxation would lower revenue and vice versa.[citation needed]

| Public finance |

|---|

|

Theory

Laffer [1] explains the model in terms of a curve describing two interacting impacts of taxation: an "arithmetic effect" and an "economic effect". The "arithmetic effect" assumes that tax revenue raised is the tax rate multiplied by the revenue available for taxation (or tax base). At a 0% tax rate, the model assumes that no tax revenue is raised. The "economic effect" assumes that the tax rate will have an impact on the tax base itself. At the extreme of a 100% tax rate, the government theoretically collects zero revenue because taxpayers change their behavior in response to the tax rate: either they have no incentive to work or they find a way to avoid paying taxes. Thus, the "economic effect" of a 100% tax rate is decreases the tax base to zero. The model assumes that somewhere between 0% and 100% lies a tax rate that will maximize revenue. Graphical representations of the curve sometimes appear to put the rate at around 50%, but the optimal rate could theoretically be any percentage greater than 0% and less than 100%, depending on the circumstances.

The point at which the curve achieves its theoretical maximum is subject to much speculation. It will vary from one economy to another and depends on the elasticity of supply for labor and various other factors. It is therefore expected to vary with time even in the same economy. Complexities arise when taking into account possible differences in incentive to work for different income groups and when introducing progressive taxation. The structure of the curve may also be changed by other policy decisions, for example, if tax loopholes and off-shore tax shelters are made more readily available by legislation, the point at which revenue begins to decrease with increased taxation will become lower.

Jude Wanniski noted [2] that all economic activity would be unlikely to cease at a 100% taxation, but would switch to barter from the exchange of money. He also noted that there can be special circumstances where economic activity can continue for a period at a 100% taxation rate (for example, in war time).

The curve is often used by advocates who want government to reduce tax rates (such as those on capital gains) and believe that the optimum tax rate is below the current tax rate. In that case, a reduction in tax rates will actually increase government revenue and not need to be offset by decreased government spending or increased borrowing.

History

Origin of the Curve

Laffer himself does not claim to have invented the concept, attributing it to 14th century Muslim scholar Ibn Khaldun and, more recently, to John Maynard Keynes. The term was reportedly coined by Jude Wanniski (a writer for The Wall Street Journal) after a 1974 afternoon meeting between Laffer, Wanniski, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and his deputy press secretary Grace-Marie Arnett (Wanniski, 2005; Laffer, 2004). In this meeting, Laffer, arguing against President Gerald Ford's tax increase, reportedly sketched the curve on a napkin[3] to illustrate the concept. Cheney did not buy the idea of supply-side economics immediately, but the idea caught the imaginations of those present[4]. Laffer professes no recollection of this napkin, but writes, "I used the so-called Laffer Curve all the time in my classes and with anyone else who would listen to me" (Laffer, 2004).

Mellon in 1924

In 1924, Secretary of Treasury Andrew Mellon wrote, "It seems difficult for some to understand that high rates of taxation do not necessarily mean large revenue to the Government, and that more revenue may often be obtained by lower rates." Exercising his understanding that "73% of nothing is nothing" he pushed for the reduction of the top income tax bracket from 73% to an eventual 24% (as well as tax breaks for lower brackets). Personal income-tax receipts rose from $719 million in 1921 to over $1 billion in 1929, which supporters attribute to the rate cut. [5]

Influence on Policy

In the United States

The Laffer curve and supply side economics inspired Reaganomics and the Kemp-Roth Tax Cut of 1981. Supply-side advocates of tax cuts claimed that lower tax rates would generate more tax revenue because the United States government's marginal income tax rates prior to the legislation were on the right-hand side of the curve. Tax revenue continued to increase, but more slowly, after the change[6].

Paul Samuelson argues in his popular economic textbook that Reagan was correct in a very limited sense to view the intuition underlying the Laffer curve as accurate, because as a successful actor, Reagan was subject to marginal tax rates as high as 90% during World War II. The point is that in a progressive tax system, any given person's perspective on the point on the curve where the economy currently sits will be influenced by the marginal tax rate to which that person's income is subject.

Influence beyond the U.S.

Between 1979 and 2002, more than 40 other countries, including the UK, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Norway, and Sweden cut their top rates of personal income tax. In an article about this, Alan Reynolds, a senior fellow with the Cato Institute, wrote, "Why did so many other countries so dramatically reduce marginal tax rates? Perhaps they were influenced by new economic analysis and evidence from... supply-side economics. But the sheer force of example may well have been more persuasive. Political authorities saw that other national governments fared better by having tax collectors claim a medium share of a rapidly growing economy (a low marginal tax) rather than trying to extract a large share of a stagnant economy (a high average tax)." [7]

Empirical evidence

Eastern Europe

Laffer, in an article published at the Heritage Foundation, has pointed to Russia and the Baltic states who have recently instituted a flat tax with rates lower than 35%, and whose economies started growing soon after implementation. He has also referred to the economic success following the Kemp-Roth tax act, the Kennedy tax cuts, the 1920s tax cuts, and the changes in US capital gains tax structure in 1997 as examples of how tax cuts can cause the economy to grow and thus increase tax revenue.[8] Others have noted that federal revenues, as a percentage of GDP, have remained stable at approximately 19.5% over the period 1950 to 2007 despite significant changes in margin tax rates over the same period. They argue that since federal revenue is proportional to GDP, the key factor in increasing revenue is to increase GDP.[9]

One study of the United States between 1959–1991 placed the revenue-maximizing tax rate (the point at which another marginal tax rate increase would decrease tax revenue) between 32.67% and 35.21%.[10] Another empirical study found that the point of maximum tax revenue in Sweden in the 1970s would have been 70%[11]

2005 CBO estimates of the effectiveness tax cuts

In 2005, the Congressional Budget Office released a paper called "Analyzing the Economic and Budgetary Effects of a 10 Percent Cut in Income Tax Rates" that casts doubt on the idea that tax cuts ultimately improve the government's fiscal situation. Unlike earlier research, the CBO paper estimates the budgetary impact of possible macroeconomic effects of tax policies, i.e., it attempts to account for how reductions in individual income tax rates might affect the overall future growth of the economy, and therefore influence future government tax revenues; and ultimately, impact deficits or surpluses. The paper's author forecasts the effects using various assumptions (e.g., people's foresight, the mobility of capital, and the ways in which the federal government might make up for a lower percentage revenue). Even in the paper's most generous estimated growth scenario, only 28% of the projected lower tax revenue would be recouped over a 10-year period after a 10% across-the-board reduction in all individual income tax rates. The paper points out that these projected shortfalls in revenue would have to be made up by federal borrowing: the paper estimates that the federal government would pay an extra $200 billion in interest over the decade covered by his analysis.[12]

Critics at the Cato Institute have charged that to support these calculations, the paper assumes that the 10% reduction in individual tax rates would only result in a 1% increase in gross national product, a figure they consider too low for current marginal tax rates in the United States.[13]

Criticism

Inappropriate Usage

Conventional economic paradigms acknowledge the basic notion of the Laffer curve. However, its role as a justification to cut taxation has been controversial. Just about everyone can agree that if an increase in tax rates leads to a decrease in tax revenues, then taxes are too high. It is also generally agreed that at some level of taxation, revenues will turn down. Proponents of tax cuts have sometimes argued that government was operating on the right-hand side of the curve, so a tax cut would increase revenue, but determining the level of taxation where revenues are maximized is a matter of debate. Pecorino (1995) argued that the peak occurred at tax rates around 65% [14]

Critics such as Paul Krugman contend that supply-side adherents did not fully believe that the United States income tax rate was on the "backwards-sloping" side of the curve and yet they still advocated lowering taxes to encourage investment of personal savings.[15]

Laffer himself proposed the curve only as a learning tool and in 2007 warned "The Laffer Curve should not be the reason you raise or lower taxes".[16]

David Stockman, President Ronald Reagan's budget director during his first administration and one of the early proponents of supply-side economics, maintained that the Laffer curve was not to be taken literally — at least not in the economic environment of the 1980s United States. In The Triumph of Politics, he writes:

- [T]he whole California gang had taken [the Laffer curve] literally (and primitively). The way they talked, they seemed to expect that once the supply-side tax cut was in effect, additional revenue would start to fall, manna-like, from the heavens. Since January, I had been explaining that there is no literal Laffer curve.

According to Nobel prize laureate James Tobin, "[t]he 'Laffer Curve' idea that tax cuts would actually increase revenues turned out to deserve the ridicule with which sober economists had greeted it in 1981."[17]

Economist John Kenneth Galbraith believed that the Reagan administration actively used the curve "to lower taxes on the affluent."[18]

Former Comptroller General of the United States David Walker stated during January 2009: "You can't have guns, butter and tax cuts. The numbers just don't add up."

During both Ronald Reagan's and George W. Bush's presidencies, White House budget staff cited in the Laffer Curve a forecast that tax rate cuts would increase overall tax revenues, but instead tax revenue increases slowed[19], requiring large debt increases to cover Reagan's and Bush's large spending increases over the short term.

Questionable assumptions

The Laffer Curve assumes that the Government will collect no tax at a 100% tax rate because there would be no incentive to earn income. However some question whether this assumption is correct. They argue, for example, that in the Soviet Union there was an effective 100% tax rate and yet, while the Soviets were not known for their efficiency, the government still managed to fund a very large and highly dispersed military while at the same time creating a highly advanced space program.[20]

Actual Results

Actual collected tax revenue in the United States from 2000 to 2007 slowed, despite tax cuts by the Bush administration aimed at raising revenue.[21]

Economist Charles Wheelan writes of the Reagan tax cuts in his book Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science, addressing overall income inequality in context to tax rate: "The tax cuts did not boost government revenues; they led to a decade and a half of large budget deficits... The wealthiest Americans may have paid more in taxes because their incomes went up sharply, not because they were working harder in response to lower tax rates."

See also

- Trickle-down economics

- Supply-side economics

- Reaganomics

- Macroeconomics

- List of economics topics

- Hauser's Law

Notes

- ^ http://www.heritage.org/Research/Taxes/bg1765.cfm

- ^ Wanniski, Jude (1978). "Taxes, Revenues and the 'Laffer Curve'". The Public Interest.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help); Text "http://www.nationalaffairs.com/doclib/20080528_197805001taxesrevenuesandthelaffercurvejudewanniski.pdf" ignored (help) - ^ http://www.polyconomics.com/gallery/Napkin003.jpg

- ^ Gellman, Barton, 258. Angler: The Cheney Vice Presidency, Penguin Press, New York 2008.

- ^ Folsom Jr., Burton W., "The Myth of the Robber Barons", page 103. Young America's Foundation, 2007.

- ^ "Receipts by Source. Retrieved from the Government Printing Office Access". GPOAccess.gov. 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ Marginal Tax Rates, by Alan Reynolds

- ^ "Laffer, A. (June 1, 2004). The Laffer Curve, Past, Present and Future. Retrieved from the Heritage Foundation". Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ DAVID RANSON, "You Can't Soak the Rich,", The Wall Street Journal, May 20, 2008; Page A23

- ^ Hsing, Y. (1996), "Estimating the Laffer curve and policy implications", Journal of Socio-Economics, 25 (3): 395–401, doi:10.1016/S1053-5357(96)90013-X, retrieved 2009-04-21

- ^ Stuart, C. (1981,October). Swedish tax rates, labor supply and tax revenues. Journal of Political Economy, 89, 1020-38.

- ^ "CBO. (December 1, 2005). Analyzing the Economic and Budgetary Effects of a 10 Percent Cut in Income Tax Rates" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ Moore, Stephen (2003-03-18). "President Bush's Economic Growth Tax Cut". CATO Institute. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ Pecorino, Paul (1995), "Tax rates and tax revenues in a model of growth through human capital accumulation", Journal of Monetary Economics, 36 (3): 527–539, doi:10.1016/0304-3932(95)01224-9

{{citation}}: External link in|title= - ^ Peddling Prosperity by Paul Krugman, p.95

- ^ Tax Cuts Don't Boost Revenues, Time Magazine, December 06, 2007

- ^ Tobin, J. (Summer 1992). Voodoo Curse. Harvard International Review, 14, p10, 4p, 1bw.

- ^ Galbraith, J.K. (Sinclair-Stevenson 1994). The World Economy Since The Wars. A Personal View, p. 232.

- ^ http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxfacts/displayafact.cfm?Docid=203

- ^ Chait, J. (September 10, 2007). Feast of the Wingnuts: How economic crackpots devoured American politics. The New Republic, 237, 27-31

- ^ Tax Cuts Don't Boost Revenues, Time Magazine, December 06, 2007