Mongolian script

| Mongolian script | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | ca.1204 – today |

| Direction | Vertical left-to-right, left-to-right |

| Languages | Mongolian language Evenki language |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Manchu script Clear script Vaghintara script |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Mong (145), Mongolian |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Mongolian |

| U+1800 – U+18AF | |

Mongolian script (Template:Lang-mn), or Hudum Mongolian script (in comparison with Todo Mongolian script), was the first of many writing systems created for the Mongolian language and the most successful until the introduction of Cyrillic to Mongolia in 1946. With minor modification, the classic vertical script is used in Inner Mongolia to this day to write both Mongolian and the Evenki language.

History

The Mongolian vertical script was developed as an adaption of the Uyghur script to write the Mongolian language. It was introduced by the Uyghur scribe Tatar-Tonga, who had been captured by the Mongols during a war against the Naimans around 1204. There were no substantive changes to the Uyghur form for the first few centuries, so that, for example, initial yodh stood for both [dʒ] and [j], while medial tsadi stood for both [dʒ] and [tʃ], and there was no letter for [d] in initial position. Mongolian sources often distinguish the early forms by using the term Uyghurjin script (Chinese: 回鹘式蒙古文, Mongolian for Uyghur style script). Western sources tend to use this term as a synonym for all variations of the Mongolian script.

Eventually, minor concessions were made to the differences between the Uyghur and Mongol languages: In the 17th and 18th centuries, smoother and more angular versions of tsadi became associated with [dʒ] and [tʃ] respectively, and in the 19th century, the Manchu hooked yodh was adopted for initial [j]. Zain was dropped as it was redundant for [s]. Various schools of orthography, some using diacritics, were developed to avoid ambiguity.

Mongolian is written vertically. The Uyghur script and its descendants—Mongolian, Oirat Clear, Manchu, and Buryat—are the only vertical scripts written from left to right. This developed because the Uyghurs rotated their Sogdian-derived script, originally written right to left, 90 degrees counterclockwise to emulate Chinese writing, but without changing the relative orientation of the letters.[1]

The characters

Characters take different shapes depending on their initial, medial, or final position within a word. In some cases, there are additional graphic variations which are selected for better visual harmony with the subsequent character.

The alphabet fails to make several vowel (o/u, ö/ü, final a/e) and consonant (t/d, k/g, sometimes ž/y) distinctions of Mongolian that were not required for Uyghur.[1] The result is somewhat comparable to the situation of English, which must represent ten or more vowels with only five letters and uses the digraph th for two distinct sounds. Sometimes, ambiguity is avoided, because the requirements of vowel harmony and syllable sequence usually determine the right choice. Moreover, as there are few words with an exactly identical spelling, actual ambiguities are rare for a reader who knows the orthography.

| Characters | Transliteration | Notes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| initial | medial | final | Latin | Cyrillic | ||

| a | А | Distinction usually by vowel harmony (see also q/γ and k/g below) | ||||

| e | Э | |||||

| i, yi | И,Й, Ы, Ь | At end of word today often absorbed into preceding syllable | ||||

| File:3mg ouöü final.png | o, u | О, У | Distinction depending on context. | |||

| File:Mg öü initial.png | File:2mg öü1 medial.pngFile:2mg öü2 medial.png | File:3mg ouöü final.png |

ö, ü | Ө, Ү | Distinction depending on context. | |

| n | Н | Distinction from medial and final a/e by position in syllable sequence. | ||||

| ng | Н, НГ | Only at end of word (medial for composites). Transcribes Tibetan ང; Sanskrit ङ. | ||||

| b | Б, В | |||||

| p | П | Only at the beginning of Mongolian words. Transcribes Tibetan པ; | ||||

| q | Х | Only with back vowels | ||||

| γ | Г | Only with back vowels. Between vowels pronounced as a long vowel.[note 5] The "final" version only appears when followed by an a written detached from the word. | ||||

| k | Х | Only with front vowels, but 'ki/gi' can occur in both front and back vowel words Word-finally only g, not k. g between vowels pronounced as long vowel.[note 6] | ||||

| g | Г | |||||

| m | М | |||||

| l | Л | |||||

| s | С | |||||

| š | Ш | |||||

| t, d | Т, Д | Distinction depending on context. | ||||

| č | Ч, Ц | Distinction between /tʃ'/ and /ts'/ in Khalkha Mongolian. | ||||

| j | Ж, З | Distinction by context in Khalkha Mongolian. | ||||

| y | -Й, Е*, Ё*, Ю*, Я* | |||||

| r | Р | Not normally at the beginning of words.[note 7] | ||||

| v | В | Used to transcribe foreign words (Originally used to transcribe Sanskrit व) | ||||

| f | Ф | Used to transcribe foreign words | ||||

| ḳ | К | Used to transcribe foreign words | ||||

| (c) | (ц) | Used to transcribe foreign words (Originally used to transcribe Tibetan /ts'/ ཚ; Sanskrit छ) | ||||

| (z) | (з) | Used to transcribe foreign words (Originally used to transcribe Tibetan /dz/ ཛ; Sanskrit ज) | ||||

| (h) | (г, х) | Used to transcribe foreign words (Originally used to transcribe Tibetan /h/ ཧ, ྷ; Sanskrit ह) | ||||

| (zh) | (-,-) | Transcribes Chinese 'zhi' - used in Inner Mongolia | ||||

| (ř) | (-,-) | Transcribes Chinese 'ri' - used in Inner Mongolia | ||||

| (chi) | (-,-) | Transcribes Chinese 'chi' - used in Inner Mongolia | ||||

Notes:

- ^ Following a consonant, Latin transliteration is i.

- ^ Following a vowel, Latin transliteration is yi, with rare exceptions like naim ("eight") or Naiman.

- ^ Character for front of syllable (n-<vowel>).

- ^ Character for back of syllable (<vowel>-n).

- ^

Examples: qa-γ-an (khan) is shortened to qaan. Some exceptions like tsa-g-aan ("white") exist.

- ^

Example: de-g-er is shortened to deer. Some exceptions like ügüi ("no") exist.

- ^ Transcribed foreign words usually get a vowel prepended. Example: Transcribing Русь (Russia) results in Oros.

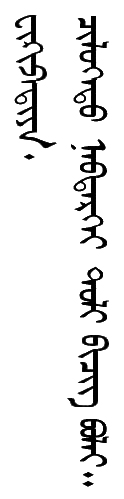

Examples

| Historical shapes | Modern print type | Transliterating first word: | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

- transliteration: Vikipediya čilügetü nebterkei toli bičig bolai.

- Cyrillic: Википедиа Чөлөөт Нэвтэрхий Толь Бичиг Болой.

- Transcription: Vikipedia chölööt nevterkhii toli bichig boloi.

- Gloss: Wikipedia free omni-profound mirror scripture is.

- Translation: Wikipedia is the free encyclopedia.

Derived scripts

Galik script

In 1587, the translator and scholar Ayuush Güüsh (Аюуш гүүш) created the Galik script (Али-гали), inspired by the 3. Dalai Lama, Sonam Gyatso. It primarily added extra characters for transcribing Tibetan and Sanskrit terms when translating religious texts, and later also from Chinese. Some of those characters are still in use today for writing foreign names (compare table above).[2]

Clear script

In 1648, the Oirat Buddhist monk Zaya-pandita Namkhaijamco created this variation with the goals of bringing the written language closer to the actual pronunciation and making it easier to transcribe Tibetan and Sanskrit. The script was used by Kalmyks of Russia until 1924, when it was replaced by the Cyrillic alphabet. In Xinjiang, China, the Oirat people still use it.

Manchu script

The Manchu script was developed from the Mongolian script in the early 17th century to write the Manchu language. A variant is still used to write the Xibe language.

Vaghintara script

Another variant was developed in 1905 by a Buryat monk named Agvan Dorjiev (1854–1938). It was also meant to reduce ambiguity, and to support the Russian language in addition to Mongolian. The most significant change however was the elimination of the positional shape variations. All characters were based on the medial variant of the original Mongol script. After a few years, Agvan-Dorjiev ran out of funds to promote his invention further, so that fewer than a dozen books were printed using it.

Mongolian in Unicode

The Unicode Mongolian block is U+1800 – U+18AF.[3] It includes letters, digits and various punctuation marks for Mongolian, Todo script, Xibe, and Manchu, as well as extensions for transcribing Sanskrit and Tibetan.

| 1800 ᠀ Birga

|

1801 ᠁ Ellipsis

|

1802 ᠂ Comma

|

1803 ᠃ Full Stop

|

1804 ᠄ Colon

|

1805 ᠅ Four Dots

|

1806 ᠆ Todo Soft Hyphen

|

1807 ᠇ Sibe Syllable Boundary Marker

|

1808 ᠈ Manchu Comma

|

1809 ᠉ Manchu Full Stop

|

180A ᠊ Nirugu

|

180B ᠋ Free Variation Selector One

|

180C ᠌ Free Variation Selector Two

|

180D ᠍ Free Variation Selector Three

|

180E Vowel Separator

|

|

| 1810 ᠐ Zero

|

1811 ᠑ One

|

1812 ᠒ Two

|

1813 ᠓ Three

|

1814 ᠔ Four

|

1815 ᠕ Five

|

1816 ᠖ Six

|

1817 ᠗ Seven

|

1818 ᠘ Eight

|

1819 ᠙ Nine

|

||||||

| 1820 ᠠ A

|

1821 ᠡ E

|

1822 ᠢ I

|

1823 ᠣ O

|

1824 ᠤ U

|

1825 ᠥ Oe

|

1826 ᠦ Ue

|

1827 ᠧ Ee

|

1828 ᠨ Na

|

1829 ᠩ Ang

|

182A ᠪ Ba

|

182B ᠫ Pa

|

182C ᠬ Qa

|

182D ᠭ Ga

|

182E ᠮ Ma

|

182F ᠯ La

|

| 1830 ᠰ Sa

|

1831 ᠱ Sha

|

1832 ᠲ Ta

|

1833 ᠳ Da

|

1834 ᠴ Cha

|

1835 ᠵ Ja

|

1836 ᠶ Ya

|

1837 ᠷ Ra

|

1838 ᠸ Wa

|

1839 ᠹ Fa

|

183A ᠺ Ka

|

183B ᠻ Kha

|

183C ᠼ Tsa

|

183D ᠽ Za

|

183E ᠾ Haa

|

183F ᠿ Zra

|

| 1840 ᡀ Lha

|

1841 ᡁ Zhi

|

1842 ᡂ Chi

|

1843 ᡃ Todo Long Vowel Sign

|

1844 ᡄ Todo E

|

1845 ᡅ Todo I

|

1846 ᡆ Todo O

|

1847 ᡇ Todo U

|

1848 ᡈ Todo Oe

|

1849 ᡉ Todo Ue

|

184A ᡊ Todo Ang

|

184B ᡋ Todo Ba

|

184C ᡌ Todo Pa

|

184D ᡍ Todo Qa

|

184E ᡎ Todo Ga

|

184F ᡏ Todo Ma

|

| 1850 ᡐ Todo Ta

|

1851 ᡑ Todo Da

|

1852 ᡒ Todo Cha

|

1853 ᡓ Todo Ja

|

1854 ᡔ Todo Tsa

|

1855 ᡕ Todo Ya

|

1856 ᡖ Todo Wa

|

1857 ᡗ Todo Ka

|

1858 ᡘ Todo Gaa

|

1859 ᡙ Todo Haa

|

185A ᡚ Todo Jia

|

185B ᡛ Todo Nia

|

185C ᡜ Todo Dza

|

185D ᡝ Sibe E

|

185E ᡞ Sibe I

|

185F ᡟ Sibe Iy

|

| 1860 ᡠ Sibe Ue

|

1861 ᡡ Sibe U

|

1862 ᡢ Sibe Ang

|

1863 ᡣ Sibe Ka

|

1864 ᡤ Sibe Ga

|

1865 ᡥ Sibe Ha

|

1866 ᡦ Sibe Pa

|

1867 ᡧ Sibe Sha

|

1868 ᡨ Sibe Ta

|

1869 ᡩ Sibe Da

|

186A ᡪ Sibe Ja

|

186B ᡫ Sibe Fa

|

186C ᡬ Sibe Gaa

|

186D ᡭ Sibe Haa

|

186E ᡮ Sibe Tsa

|

186F ᡯ Sibe Za

|

| 1870 ᡰ Sibe Raa

|

1871 ᡱ Sibe Cha

|

1872 ᡲ Sibe Zha

|

1873 ᡳ Manchu I

|

1874 ᡴ Manchu Ka

|

1875 ᡵ Manchu Ra

|

1876 ᡶ Manchu Fa

|

1877 ᡷ Manchu Zha

|

||||||||

| 1880 ᢀ Ali Gali Anusvara One

|

1881 ᢁ Ali Gali Visarga One

|

1882 ᢂ Ali Gali Damaru

|

1883 ᢃ Ali Gali Ubadama

|

1884 ᢄ Ali Gali Inverted Ubadama

|

1885 ᢅ Ali Gali Baluda

|

1886 ᢆ Ali Gali Three Baluda

|

1887 ᢇ Ali Gali A

|

1888 ᢈ Ali Gali I

|

1889 ᢉ Ali Gali Ka

|

188A ᢊ Ali Gali Nga

|

188B ᢋ Ali Gali Ca

|

188C ᢌ Ali Gali Tta

|

188D ᢍ Ali Gali Ttha

|

188E ᢎ Ali Gali Dda

|

188F ᢏ Ali Gali Nna

|

| 1890 ᢐ Ali Gali Ta

|

1891 ᢑ Ali Gali Da

|

1892 ᢒ Ali Gali Pa

|

1893 ᢓ Ali Gali Pha

|

1894 ᢔ Ali Gali Ssa

|

1895 ᢕ Ali Gali Zha

|

1896 ᢖ Ali Gali Za

|

1897 ᢗ Ali Gali Ah

|

1898 ᢘ Todo Ali Gali Ta

|

1899 ᢙ Todo Ali Gali Zha

|

189A ᢚ Manchu Ali Gali Gha

|

189B ᢛ Manchu Ali Gali Nga

|

189C ᢜ Manchu Ali Gali Ca

|

189D ᢝ Manchu Ali Gali Jha

|

189E ᢞ Manchu Ali Gali Tta

|

189F ᢟ Manchu Ali Gali Ddha

|

| 18A0 ᢠ Manchu Ali Gali Ta

|

18A1 ᢡ Manchu Ali Gali Dha

|

18A2 ᢢ Manchu Ali Gali Ssa

|

18A3 ᢣ Manchu Ali Gali Cya

|

18A4 ᢤ Manchu Ali Gali Zha

|

18A5 ᢥ Manchu Ali Gali Za

|

18A6 ᢦ Ali Gali Half U

|

18A7 ᢧ Ali Gali Half Ya

|

18A8 ᢨ Manchu Ali Gali Bha

|

18A9 ᢩ Ali Gali Dagalga

|

18AA ᢪ Manchu Ali Gali Lha

|

|||||

Issues

Although the Mongolian script has been defined in Unicode since 1999, there was no support for Unicode Mongolian from the major vendors until the release of the Windows Vista operating system in 2007, and so Unicode Mongolian is not yet widely used. In China, legacy encodings such as the Private Use Area (PUA) Unicode mappings and GB18030 mappings of the Menksoft IMEs (espc. Menksoft Mongolian IME) are more commonly used than Unicode for writing web pages and electronic documents in Mongolian.

The inclusion of a Unicode Mongolian font and keyboard layout in Windows Vista has meant that Unicode Mongolian is now gradually becoming more popular, but the complexity of the Unicode Mongolian encoding model and the lack of a clear definition for the use variation selectors are still barriers to its widespread adoption.

However, there are bugs in Microsoft's Mongolian Baiti font.[4]

References

- ^ a b György Kara, "Aramaic Scripts for Altaic Languages", in Daniels & Bright The World's Writing Systems, 1994.

- ^ Otgonbayar Chuluunbaatar (2008). Einführung in die Mongolischen Schriften (in German). Buske. ISBN 978-3-87548-500-4.

- ^ Unicode block U+1800 – U+18AF; Mongolian.

- ^ Version 5.00 of the Mongolian Baiti font may be displayed incorrectly in Windows Vista