Ray Bradbury

Ray Bradbury | |

|---|---|

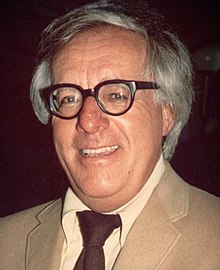

Bradbury in 1975 | |

| Occupation | Novelist, Short story writer, Essayist. |

| Nationality | USA |

| Genre | Science fiction, fantasy, horror, mystery, social science fiction, dark fantasy |

| Notable works | The Martian Chronicles, Fahrenheit 451, Fever Dream |

| Signature | |

| Website | |

| http://www.raybradbury.com/ | |

Ray Douglas Bradbury (born August 22, 1920) is an American fantasy, horror, science fiction, and mystery writer. Best known for his dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451 (1953) and for the science fiction stories gathered together as The Martian Chronicles (1950) and The Illustrated Man (1951), Bradbury is one of the most celebrated among 20th and 21st century American writers of speculative fiction.[citation needed] Bradbury's popularity has been increased by more than 20 filmed dramatizations of his works. (See Adaptations of his work.)

Beginnings

Bradbury was born in Waukegan, Illinois, to a Swedish immigrant mother and a father who was a power and telephone lineman.[3] His paternal grandfather and great-grandfather were newspaper publishers. He is also somewhat distantly related to the American Spalding family, owners of the famous Spalding sports equipment company. His title character Douglas Spaulding,from the novel Dandelion Wine was reportedly drawn from this heritage. He is also reputedely and ironically related to the American Shakespeare scholar Douglas Spaulding.

Bradbury was a reader and writer throughout his youth, spending much time in the Carnegie library in Waukegan, Illinois. He used this library as a setting for much of his novel Something Wicked This Way Comes, and depicted Waukegan as "Green Town" in some of his other semi-autobiographical novels—Dandelion Wine, Farewell Summer—as well as in many of his short stories.[4]

He attributes his lifelong habit of writing every day to an incident in 1932 when a carnival entertainer, Mr. Electrico,[5] touched him on the nose with an electrified sword, made his hair stand on end, and shouted, "Live forever!" It was from then that Bradbury wanted to live forever and decided his career as an author in order to do what he was told: live forever. It was at that age that Bradbury first started to do magic. Magic was his first great love. If he had not discovered writing, he would have become a magician.[6]

The Bradbury family lived in Tucson, Arizona, in 1926–27 and 1932–33 as his father pursued employment, each time returning to Waukegan, but eventually settled in Los Angeles in 1934, when Ray was thirteen.

Bradbury graduated from the Los Angeles High School in 1938 but did not attend college. Instead, he sold newspapers at the corner of South Norton Avenue and Olympic Boulevard. In regard to his education, Bradbury said:

"Libraries raised me. I don’t believe in colleges and universities. I believe in libraries because most students don’t have any money. When I graduated from high school, it was during the Depression and we had no money. I couldn’t go to college, so I went to the library three days a week for 10 years."[7]

Having been influenced by science fiction heroes like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, he began to publish science fiction stories in fanzines in 1938. Bradbury was invited by Forrest J Ackerman to attend the now legendary Los Angeles Science Fiction Society, which at the time met at Clifton’s Cafeteria in downtown Los Angeles. This was where he met the writers Robert A. Heinlein, Emil Petaja, Fredric Brown, Henry Kuttner, Leigh Brackett, and Jack Williamson. His first published story was "Hollerbochen's Dilemma", which appeared in the fan magazine Imagination! in January, 1938. Launching his own fanzine in 1939, titled Futuria Fantasia, he wrote most of its four issues, each limited to under 100 copies. Between 1940 and 1947, he was a contributor to Rob Wagner's film magazine, Script.

Bradbury's first paid piece, "Pendulum", written with Henry Hasse, was published in the pulp magazine Super Science Stories in November 1941, for which he earned $15.[8] He became a full-time writer by the end of 1942. His first book, Dark Carnival, a collection of short works, was published in 1947 by Arkham House, a firm owned by writer August Derleth.

A chance encounter in a Los Angeles bookstore with the British expatriate writer Christopher Isherwood gave Bradbury the opportunity to put The Martian Chronicles into the hands of a respected critic. Isherwood's glowing review followed and substantially boosted Bradbury's career.

Ray Bradbury married Marguerite McClure (1922–2003) in 1947, and they had four daughters. To date, Bradbury has never obtained a driver license.[9]

Works

Although he is often described as a science fiction writer, Bradbury does not box himself into a particular narrative categorization:

First of all, I don't write science fiction. I've only done one science fiction book and that's Fahrenheit 451, based on reality. Science fiction is a depiction of the real. Fantasy is a depiction of the unreal. So Martian Chronicles is not science fiction, it's fantasy. It couldn't happen, you see? That's the reason it's going to be around a long time—because it's a Greek myth, and myths have staying power.[10]

On another occasion, Bradbury observed that the novel touches on the alienation of people by media:

In writing the short novel Fahrenheit 451 I thought I was describing a world that might evolve in four or five decades. But only a few weeks ago, in Beverly Hills one night, a husband and wife passed me, walking their dog. I stood staring after them, absolutely stunned. The woman held in one hand a small cigarette-package-sized radio, its antenna quivering. From this sprang tiny copper wires which ended in a dainty cone plugged into her right ear. There she was, oblivious to man and dog, listening to far winds and whispers and soap-opera cries, sleep-walking, helped up and down curbs by a husband who might just as well not have been there. This was not fiction.[11]

Besides his fiction work, Bradbury has written many short essays on the arts and culture, attracting the attention of critics in this field. Bradbury was a consultant for the American Pavilion at the 1964 New York World's Fair and the original exhibit housed in Epcot's Spaceship Earth geosphere at Walt Disney World.[12][13][14]

Bradbury was a close friend of Charles Addams and Addams illustrated the first of Bradbury's stories about the Elliotts, a family that would resemble Addams' own Addams Family placed in rural Illinois. Bradbury's first story about them was "Homecoming," published in the New Yorker Halloween issue for 1946, with Addams illustrations. He and Addams planned a larger collaborative work that would tell the family's complete history, but it never materialized and according to a 2001 interview they went their separate ways.[15] In October 2001, Bradbury published all the Family stories he had written in one book with a connecting narrative, From the Dust Returned, featuring a wraparound Addams cover of the original 'Homecoming' illustration.[16]

Adaptations

From 1951 to 1954, 27 of Bradbury's stories were adapted by Al Feldstein for EC Comics, and 16 of these were collected in the paperbacks, The Autumn People (1965) and Tomorrow Midnight (1966), both published by Ballantine Books with cover illustrations by Frank Frazetta.

Also in the early 1950s, adaptations of Bradbury's stories were televised on a variety of anthology shows, including Tales of Tomorrow, Lights Out, Out There, Suspense, CBS Television Workshop, Jane Wyman's Fireside Theatre, Star Tonight, Windows and Alfred Hitchcock Presents. "The Merry-Go-Round," a half-hour film adaptation of Bradbury's "The Black Ferris," praised by Variety, was shown on Starlight Summer Theater in 1954 and NBC's Sneak Preview in 1956.

Director Jack Arnold first brought Bradbury to movie theaters in 1953 with It Came from Outer Space, a Harry Essex screenplay developed from Bradbury's screen treatment, "The Meteor". Three weeks later, Eugène Lourié's The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), based on Bradbury's "The Fog Horn," about a sea monster mistaking the sound of a fog horn for the mating cry of a female, was released. Bradbury's close friend Ray Harryhausen produced the stop-motion animation of the creature. Bradbury would later return the favor by writing a short story, "Tyrannosaurus Rex", about a stop-motion animator who strongly resembled Harryhausen. Over the next 50 years, more than 35 features, shorts, and TV movies were based on Bradbury's stories or screenplays.

Bradbury's short story I Sing the Body Electric (from the book of the same name) was adapted for the 100th episode of the American TV series The Twilight Zone. The episode was first aired on 18 May 1962.

Oskar Werner and Julie Christie starred in Fahrenheit 451 (1966), an adaptation of Bradbury's novel directed by François Truffaut.

In 1969, The Illustrated Man was brought to the big screen, starring Oscar winner Rod Steiger, Claire Bloom, & Robert Drivas. Containing the prologue, and three short stories from the book, the film received mediocre reviews.

The Martian Chronicles became a three-part TV miniseries starring Rock Hudson which was first broadcast by NBC in 1980. Bradbury found the miniseries "just boring".[17]

The 1983 horror film Something Wicked This Way Comes, starring Jason Robards and Jonathan Pryce, is based on the Bradbury novel of the same name.

In 1984, Michael McDonough of Brigham Young University produced "Bradbury 13," a series of thirteen audio adaptations of famous Ray Bradbury stories, in conjunction with National Public Radio. The full-cast dramatizations featured adaptations of "The Man," "The Ravine," "Night Call, Collect," "The Veldt," "Kaleidoscope," "There Was an Old Woman," "Here There Be Tygers," "Dark They Were, and Golden-Eyed," "The Wind," "The Fox and the Forest," "The Happiness Machine," "The Screaming Woman", and "A Sound of Thunder". Voiceover actor Paul Frees provided narration, while Bradbury himself was responsible for the opening voiceover; Greg Hansen and Roger Hoffman scored the episodes. The series won a Peabody Award as well as two Gold Cindy awards. The series has not yet been released on CD but is heavily traded by fans of "old time radio".

From 1985 to 1992 Bradbury hosted a syndicated anthology television series, The Ray Bradbury Theater, for which he adapted 65 of his stories. Each episode would begin with a shot of Bradbury in his office, gazing over mementoes of his life, which he states (in narrative) are used to spark ideas for stories. During the first two seasons, Bradbury also provided additional voiceover narration specific to the featured story, and appeared on-screen.

Five episodes of the USSR science fiction TV series This Fantastic World adapted Ray Bradbury's stories I Sing The Body Electric, Fahrenheit 451, A Piece of Wood, To the Chicago Abyss, and Forever and the Earth.[18] A Soviet adaptation of "The Veldt" was filmed in 1987.[19]

The 1998 film The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit, released by Touchstone Pictures, was written by Ray Bradbury. It was based on his story "The Magic White Suit" originally published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1957. The story had also previously been adapted as a play, a musical, and a 1958 television version.

In 2002, Bradbury's own Pandemonium Theatre Company production of Fahrenheit 451 at Burbank's Falcon Theatre combined live acting with projected digital animation by the Pixel Pups. In 1984 Telarium released a video game for Commodore 64 based on Fahrenheit 451.[20] Bradbury and director Charles Rome Smith co-founded Pandemonium in 1964, staging the New York production of The World of Ray Bradbury (1964), adaptations of "The Pedestrian," "The Veldt", and "To the Chicago Abyss."

In 2005, the film A Sound of Thunder was released, loosely based upon the short story of the same name.[21] Short film adaptations of A Piece of Wood and The Small Assassin were released in 2005 and 2007 respectively.[22][23]

In 2008, the film Ray Bradbury's Chrysalis was produced by Roger Lay Jr for Urban Archipelago Films, based upon the short story of the same name. The film went on to win the best feature award at the International Horror and Sci-Fi Film Festival in Phoenix. The film has been picked up for international distribution by Arsenal Pictures and for domestic distribution by Lightning Entertainment.[24]

A new film version of Fahrenheit 451 is being planned by director Frank Darabont.

Honors

- In 2007, Bradbury received the French Commandeur Ordre des Arts et des Lettres medal.

- For his contribution to the motion picture industry, Ray Bradbury was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6644 Hollywood Blvd.

- An asteroid is named in his honor, "9766 Bradbury," along with a crater on the moon called "Dandelion Crater" (named after his novel, Dandelion Wine).

- On April 16, 2007, Bradbury received a special citation from The Pulitzer Board, "for his distinguished, prolific, and deeply influential career as an unmatched author of science fiction and fantasy."[25]

- On November 17, 2004, Bradbury was the recipient of the National Medal of Arts, presented by then-President George W. Bush and Laura Bush. Bradbury has also received the World Fantasy Award life achievement, Stoker Award life achievement, SFWA Grand Master, SF Hall of Fame Living Inductee, and First Fandom Award. He received an Emmy Award for his work on The Halloween Tree. He received the Prometheus Award for Fahrenheit 451.

- One short film he worked on, Icarus Montgolfier Wright[26] was nominated for an Academy Award, but Bradbury himself has not been.

- Ray Bradbury Park was dedicated in Waukegan, Illinois in 1990. The author was present for the ribbon-cutting ceremony. The park contains locations described in "Dandelion Wine", most notably the staircase. In 2009 an interpretive panel designed by artist Michael Pavelich was added to the park detailing the history of Ray Bradbury and Ray Bradbury Park.

- Honorary doctorate from Woodbury University in 2003. Bradbury presents the Ray Bradbury Creativity Award each year at Woodbury University. Winners include sculptor Robert Graham, actress Anjelica Huston, Cosmopolitan editor Helen Gurley Brown, director Irvin Kershner, humorist Stan Freberg, and architect Jon A. Jerde.

- Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters Award for 2000 from the National Book Foundation.[27]

- In 2008, he was named SFPA Grandmaster.[28]

- The Ray Bradbury Award, presented by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America for screenwriting, was named in Bradbury's honor.

Fahrenheit 9/11

In 2005 it was reported that Bradbury was upset with filmmaker Michael Moore for using the title Fahrenheit 9/11, which is an allusion to Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, for his documentary about the George W. Bush administration. Bradbury expressed displeasure with Moore's use of the title but stated that his resentment was not politically motivated. Bradbury asserts that he does not want any of the money made by the movie, nor does he believe that he deserves it. He pressured Moore to change the name, but to no avail. Moore called Bradbury two weeks before the film's release to apologize, saying that the film's marketing had been set in motion a long time ago and it was too late to change the title.[29]

Documentaries

- Bradbury's works and approach to writing are documented in Terry Sanders' film Ray Bradbury: Story of a Writer (1963).

See also

Notes

- ^ The Rough Guide To Cult Fiction", Tom Bullough, et al., Penguin Books Ltd, London, 2005, p.35

- ^ King, Stephen (1981). Stephen King's danse macabre. Macdonald. p. [page needed]. ISBN 0354046470.

My first experience of real horror came at the hands of Ray Bradbury.

- ^ Certificate of Birth, Ray Douglas Bradbury, August 22, 1920, Lake County Clerk's Record #4750. Although he was named after Rae Williams, a cousin on his father's side, Ray Bradbury's birth certificate spells his first name as "Ray."

- ^ Sites from these works which still exist in Waukegan include his boyhood home, his grandparents' home next door (and their connecting lawns where he and his grandfather gathered dandelions to make wine) and, less than a block away, the famous ravine which Bradbury used as a metaphor throughout his career.

- ^ "In His Words". RayBradbury.com. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ^ Terry Sanders' film Ray Bradbury: Story of a Writer (1963)

- ^ Steinhauer, Jennifer (2009-06-19). "A Literary Legend Fights for a Local Library". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ^ "Biographies: Bradbury, Raymond Douglas". s9.com. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ^ Riddle, Warren (2009-06-25). "Sci-Fi Author Ray Bradbury Trashes the Web". Switched. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ^ wil gerken, nathan hendler, doug floyd, john banks. "Books: Grandfather Time (Weekly Alibi . 09-27-99)". Weeklywire.com. Retrieved 2010-02-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Quoted by Kingsley Amis in New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction (1960).

- ^ Ray Bradbury. "In 1982 he created the interior metaphors for the Spaceship Earth display at Epcot Center, Disney World." http://www.raybradbury.com/bio.html

- ^ Ray Bradbury. "The images at Spaceship Earth in DisneyWorld's EPCOT Center in Orlando? Well, they are all Bradbury's ideas." http://www.raybradbury.com/articles_town_talk.html

- ^ Ray Bradbury. "He also serves as a consultant, having collaborated, for example, in the design of a pavilion in the Epcot Center at Walt Disney World." Referring to Spaceship Earth ...http://www.raybradbury.com/articles_book_mag.html

- ^ Interview with Ray Bradbury in IndieBound, fall 2001.

- ^ Bradbury, Ray, From The Dust Returned: A Novel. William Morrow, 2001.

- ^ Weller, Sam (2005). The Bradbury Chronicles: The Life of Ray Bradbury. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 301–302. ISBN 0-06-054581-X.

- ^ "State Fund of Television and Radio Programs" (in Russian).

- ^ Veld at IMDb

- ^ "Fahrenheit 451 (1984 game)".

- ^ A Sound of Thunder at IMDb

- ^ A Piece of Wood at IMDb

- ^ The Small Assassin at IMDb

- ^ Chrysalis at IMDb

- ^ 2007 Special Awards from the Pulitzer Prize website

- ^ Icarus Montgolfier Wright at IMDb

- ^ Distinguished Contribution to American Letters Award with his acceptance speech.

- ^ Wilson, Stephen M. (2008). "2008 SFPA Grandmaster". The Science Fiction Poetry Association. SFPA. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ^ Weller, Sam (2005). The Bradbury Chronicles: The Life of Ray Bradbury. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 330–331. ISBN 0-06-054581-X.

References

- Tuck, Donald H. (1974). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Chicago: Advent. pp. 61–63. ISBN 0-911682-20-1.

- William F. Nolan, The Ray Bradbury Companion: A Life and Career History, Photolog, and Comprehensive Checklist of Writings, Gale Research (1975). Hardcover, 339 pages. ISBN 0-8103-0930-0

- Donn Albright, Bradbury Bits & Pieces: The Ray Bradbury Bibliography, 1974-88, Starmont House (1990). ISBN 155742151X. Never published but available in manuscript at The Center for Ray Bradbury Studies.

- Robin Anne Reid, Ray Bradbury: A Critical Companion, Greenwood Press (2000). 133 pages. ISBN 0313309019

- Jerry Weist, Bradbury, an Illustrated Life: A Journey to Far Metaphor, William Morrow & Company (2002). Hardcover, 208 pages. ISBN 0-06-001182-3

- Jonathan R. Eller and William F. Touponce, Ray Bradbury: The Life of Fiction, Kent State University Press (2004). Hardcover, 570 pages. ISBN 0-87338-779-1

- Sam Weller, The Bradbury Chronicles: The Life of Ray Bradbury, HarperCollins (2005). Hardcover, 384 pages. ISBN 0-06-054581-X

External links

- Ray Bradbury - Official Website

- Bradburymedia - detailed coverage of Bradbury's work in film, TV, radio, theatre

- Please use a more specific IMDb template. See the documentation for available templates.

- Ray Bradbury at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Center for Ray Bradbury Studies

- Ray Bradbury: Story of a Writer, film by Terry Sanders

- Illustrated guide to Bradbury's stories (English, Polish and Russian languages)

- Survey of Bradbury Scholarship - Chronological analysis of Bradbury criticism

- Full stories list with filter by collection, year and alphabet

- 1920 births

- American fantasy writers

- American horror writers

- American novelists

- American science fiction writers

- American screenwriters

- American short story writers

- American Unitarian Universalists

- Authors of books about writing fiction

- Commandeurs of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

- Hugo Award winning authors

- Living people

- People from Waukegan, Illinois

- Prometheus Award winning authors

- Pulitzer Prize winners

- Pulp fiction writers

- Science fiction fans

- Science Fiction Hall of Fame

- SFWA Grand Masters

- American people of Swedish descent

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- Worldcon Guests of Honor

- Winners of the Sir Arthur Clarke Award

- Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award winners