Battle of Verdun

| Battle of Verdun | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of the First World War | |||||||

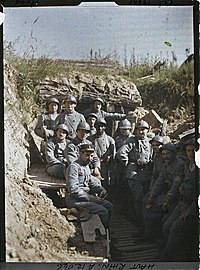

A French trench in northeastern France | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| About 30,000 on 21 February 1916 | About 150,000 on 21 February 1916 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 542,000[3]-400,000[4]; of whom 163,000 died | 434,000[5]-355,000[6]; of whom 143,000 died | ||||||

The Battle of Verdun (French: Bataille de Verdun, IPA: [bataj də vɛʁdœ̃], German: Schlacht um Verdun) was one of the major battles during the First World War on the Western Front. It was fought between the German and French armies, from 21 February to 18 December 1916, on hilly terrain north of the city of Verdun-sur-Meuse in north-eastern France. The Battle of Verdun ended in a French victory since the German High Command failed to achieve its two strategic objectives: the capture of the city of Verdun and a much higher casualty count inflicted on the French adversary. As a whole, the Battle of Verdun resulted in more than a quarter of a million battlefield deaths and at least half a million wounded. Verdun was the longest battle and one of the most devastating in the First World War and more generally in human history. A total of about 40 million artillery shells were exchanged by both sides, leaving behind an endless field of shell craters that are still partly visible today. In both France and Germany, Verdun has come to represent the horrors of war, similar to the significance of the Battle of the Somme to the United Kingdom. Major General Julian Thompson, a renowned British military historian, has referred to Verdun in the History Channel's: 1916: Total War, as "France's Stalingrad".

The Battle of Verdun popularized at the time General Robert Nivelle's: Ils ne passeront pas ("They shall not pass"), a phrase he delivered in an official order of the day on June 23, 1916, at the time of the critical combat for Fort Souville (in: Denizot, Alain, 1996, "Verdun 1914–1918", Nouvelles Editions Latines, Paris, ISBN 2-7233-0514-7 based on his Sorbonne Ph.D. thesis). At the beginning of the Battle of Verdun, on 16 April 1916, General Philippe Pétain had already issued a reassuring order of the day ending with: Courage! On les aura ("Courage! We shall get them"). These admonitions betray a sense of concern by the French leadership at the morale problems which would sporadically manifest themselves at Verdun during the late summer and fall of 1916. Those would later culminate into the French army mutinies that followed after the Nivelle offensive of April 1917 (Denizot,1996).

Historical background

For centuries, Verdun had played an important role in the defence of its hinterland, due to the city's strategic location on the Meuse River. Attila the Hun, for example, failed in his 5th-century attempt to seize the town. In the division of the empire of Charlemagne, the Treaty of Verdun of 843 made the town part of the Holy Roman Empire. The Peace of Munster in 1648 awarded Verdun to France. Verdun played a very important role in the defensive line that was built after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. As a protection against German threats along the eastern border, a strong line of fortifications was constructed between Verdun and Toul and between Épinal and Belfort. Verdun guarded the northern entrance to the plains of Champagne, and thus the approach to the French capital city of Paris.

Verdun sector in 1914

In 1914, during the German invasion of France, a salient was created around Verdun by the First Battle of the Marne (5 to 12 September) and the capture of Saint-Mihiel (on September 24). Although some forts underwent Big Bertha's artillery bombardment, the fortifications were not threatened with capture.

The heart of the city of Verdun was a citadel built by Vauban in the 17th century. By the end of the 19th century, a large underground complex had also been built which served as quarters for the troops inside the city. About 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) beyond the walls of the city of Verdun was an outer circular ring of 18 large underground forts (not including 12 smaller forts or redoubts), many of them featuring retractable/rotating artillery turrets equipped with short 75 mm and short 155 mm fortress cannons. This ring of 18 large underground forts protecting Verdun had been built at great cost during the 1880s[7] and according to the specifications of the Séré de Rivières system. The Verdun forts were variable in quality and size, and thus provided unequal potential to resist heavy artillery shelling.

The forts situated to the north and east of Verdun (e.g. Fort Douaumont, Fort Vaux, Moulainville) had been thoroughly hardened during the early 1900s with very thick steel-reinforced concrete tops resting on a sand cushion. Those hardened forts had also been equipped with regular 75 mm field guns installed in reinforced concrete bunkers ("Casemates de Bourges") looking sideways, thus providing flanking fire across the intervals between the forts. However, several large forts built during the 1880s on the same defensive ring, but to the west and south of Verdun (e.g. La Chaume, Regret, Belrupt-en-Verdunois), had never been improved. The prediction was that a German assault would come from the east and north and this later proved to be essentially correct.

German strategy

After the German invasion of France had been halted at the First Battle of the Marne, in September 1914, the war of movement gave way to trench warfare with neither side being able to achieve a successful breakthrough.

In 1915, all attempts to force a breakthrough by the Germans at Ypres, by the British at Neuve Chapelle and by the French at Battle of Champagne and Battle of Artois had failed, resulting only in very heavy casualties.

According to his post-war memoirs, the German Chief of Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, believed that, although a major breakthrough might no longer be achieved, the French army could still be defeated if it suffered a sufficient number of casualties. He explained that his motivation for the battle was to attack a position from which the French army could not retreat, both for strategic reasons and for reasons of national pride. Verdun, surrounded by a ring of forts, was a stronghold and a salient that projected into the German lines and blocked an important railway line leading to Paris.

However, by early 1916, Verdun's much-vaunted impregnability had been seriously weakened. General Joffre had concluded, from the easy fall of the Belgian fortresses at Liège and at Namur, that this type of defensive system was obsolete and could no longer withstand shelling by the German heavy siege guns. Consequently, during 1915, the Verdun sector was denuded of over 50 complete batteries and 128,000 rounds of artillery ammunition. This stripping process was still in progress at the end of January 1916. By that time, the 18 major forts and other batteries surrounding Verdun were left with fewer than 300 guns and limited ammunition. Furthermore, their garrisons had been reduced to small maintenance crews.

In choosing Verdun, Falkenhayn had opted for a location where material circumstances favoured a successful German offensive: Verdun was isolated on three sides and railway communications to the French rear were restricted. Conversely, a German controlled major rail head lay only 20 kilometres (12 mi) to the north of their positions. In a war where materiel trumped élan, Falkenhayn expected a favourable loss exchange ratio as the French would cling fanatically to a death trap.

Falkenhayn claimed in his memoirs that, rather than a traditional military victory, Verdun was planned as a vehicle for destroying the French Army. He quotes in his book from a memo he says he wrote to the Kaiser:

The string in France has reached breaking point. A mass breakthrough—which in any case is beyond our means—is unnecessary. Within our reach there are objectives for the retention of which the French General Staff would be compelled to throw in every man they have. If they do so the forces of France will bleed to death.

However, recent German scholarship by Holger Afflerbach and others has questioned the veracity of this so-called "Christmas memo".[8] No copy has ever surfaced and the only account of it appeared in Falkenhayn's post-war memoir. His army commanders at Verdun, including the German Crown Prince, denied any knowledge of a plan based on attrition. Afflerbach argues that it seems likely that Falkenhayn did not specifically design the battle to bleed the French Army, but proposed ex-post-facto the motive of the Verdun offensive, to justify its failure.

Current analyses follow the same trend and exclude the traditional explanation. The offensive was probably planned to overwhelm Verdun's weakened defences, thus striking a potentially fatal blow at the French Army. Again, Verdun's peacetime rail communications had been cut off in 1915 and thus the city and its ring of forts were depending on a single narrow road (the future "Voie sacrée") and a local narrow-gauge railway (the "Chemin de fer Meusien") to be re-supplied. This logistical bottleneck had raised German hopes that an effective French defence of the Verdun sector could not be sustained beyond a few weeks.

Prelude

As previously stated, the Verdun sector was poorly defended in 1916 because half of the artillery in the forts had been taken away during 1915, leaving only the heavy guns in the retractable gun turrets. The highly effective 75 mm guns in the "Casemates de Bourges" had all been removed. Furthermore, there were no continuous barbed wire belts around the forts and most of the forts' machine guns were still boxed up in underground storage. By a fluke of bureaucratic incoherence, the forts had been placed under the control of a general officer who was not reporting to the local commander of the Verdun Military Sector. Instead he took his orders directly from Paris. Consequently, when the local commander of the Verdun Military Sector showed up to inspect Fort Douaumont, one month before the battle, he was refused access because he did not carry the necessary papers. In February 1916, French intelligence on German preparations and a delay in the attack due to bad weather gave the French High Command time to rush two divisions from the 30th Corps—the 72nd and 51st—to the area's defence. The French strength at Verdun was now 34 battalions against 72 German battalions, therefore, about half that of the assailant. French artillery was even more at a disadvantage: about 300 guns, mostly 75 mm field guns, versus 1400 guns on the German side most of them heavy and super heavy including 14-inch and 16-inch mortars.

February–April 1916

The German High Command aimed to launch the offensive on the 12 February; however, fog, heavy rain and high winds delayed the offensive for a week, hence the battle began on 21 February 1916 at 7:15 am with a ten-hour artillery bombardment firing over 1,000,000 shells (including poison gas) by 1,400 guns, most of them heavies, on a front of 40 kilometres (25 miles). This incessant pounding or " Trommelfeuer" ("drum fire") was the heaviest and longest artillery preparation ever inflicted since the beginning of the First World War. The noise it produced was carried through the ground as a rumble that was still heard one hundred miles away. This massive preparation was followed by an attack by three army corps (the 3rd, 7th, and 18th). The Germans used flamethrowers for the first time to clear the French trenches. Newly introduced storm troops led the attack with rifles slung, the first time in the war, and went into battle with grenades in hand. Combined artillery and infantry shock tactics on that scale were new to the French defenders and caused them to lose much ground to the Germans at the beginning. The bombardment completely pulverized the French trenches, phone lines, and artillery. French forces took massive losses during this bombardment. Some soldiers were ripped to pieces or buried underneath the earth, and human remains were seen hanging in tree branches.[9] German forces then began their push. French forces resisted from all sides, and by the end of the first day, the Germans had sufferd about 600 casualties.[9][10]

By 22 February, German shock troops had advanced three miles (5 km) capturing the Bois des Caures, at the edge of the village of Flabas, after two French battalions led by Colonel Émile Driant had held them up for two days, and pushed the French defenders back to Samogneux, Beaumont, and Ornes. Later that day, on 22 February, French Colonel Émile Driant was killed, rifle in hand, fighting alongside the 56th and 59th Bataillon de chasseurs à pied. Only 118 Chasseurs managed to escape. Poor communications meant that only then did the French high command realise the seriousness of the attack. The Germans managed to take the village of Haumont, but French forces repulsed a German attack on the village of Bois de l'Herbebois.[9]

On 23 February, a French counterattack at Bois des Caures was repulsed. Fierce fighting at Bois de l'Herbebois continued, but the Germans managed to flank the French defenders from Bois de Wavrille and capture the town. The Germans also suffered heavy casualties during their attack on Bois de Fosses. French forces managed to retain control of the village of Samogneux, despite heavy fighting. However, the Germans continued to drive the French from their first line of defense.[9]

On 24 February, the French defenders of XXX Corps fell back again from their second line of defense, but were saved from disaster by the appearance of the XX Corps under General Maurice Balfourier. Intended as relief, the new arrivals were thrown into combat immediately. That evening French Army chief of staff, General de Castelnau, advised his commander-in-chief, General Joffre, that the French Second Army, under General Philippe Pétain, ought to be brought up to reinforce the Verdun sector. In the meantime, the Germans were now in possession of Beaumont, the Bois des Fosses, the Bois des Caurières and were moving up the Hassoule ravine which led directly to Fort Douaumont.

On 24 February, at 4:30 pm, infantrymen from three companies of the German 24th (Brandenburg) regiment entered the centrepiece of the French fortification system: Fort Douaumont. The first German party to find an entry into the fort was led by a Sergeant Kunze. He was followed by other raiders led by Lieutenant Cordt von Brandis, Lieutenant Radtke, and Captain Haupt. The whole German raiding party, made up of only 19 officers and 79 soldiers, promptly overwhelmed the small French garrison (68 men) and forced its surrender.

Douaumont was known as the largest fort of the Verdun's defensive system. It had been built before the war to hold a garrison of 477 men and 7 commissioned officers. It also featured two retractable/rotating artillery turrets plus 4 × 75 mm field guns firing from side bunkers. However, the reality of Douaumont's situation in February 1916 was quite different. Firstly, a single NCO named Chenot was the highest ranking military personnel inside Fort Douaumont and its de facto commander. Ordnance wise, only one rotating gun turret, out of the four in existence, was properly armed and manned by a crew of artillerymen. The drawbridge, which had been immobilized in the down position by a German shell, had never been repaired. All the fort's 75 mm guns in side bunkers had been removed in 1915, following orders given by General Joffre. The fort's moats were basically left undefended and preparations had been made to blow up the fort from the inside. Captain Haupt, being the senior officer in the raiding party that captured Douaumont, took command of the fort. However he was wounded the next morning and had to delegate his command to Oberleutnant von Brandis CO of 8th Kompanie. Both von Brandis and Haupt won the highest German military decoration, Pour le Mérite, for the extraordinary courage and initiative they had shown during this successful action. Von Brandis, who spoke French fluently, had also played a key role in persuading the fort's small garrison to surrender[citation needed]. The final recapture of Fort Douaumont, on 24 October 1916, was estimated at a later date to have cost the French Army at least 100,000 casualties.

Castelnau appointed General Philippe Pétain commander of the Verdun area and ordered the French Second Army to the battle sector. Pétain took over on 25 February and decided that the Verdun forts should be strongly re-garrisoned to form the principal bulwarks of a new defence. He mapped out new lines of resistance on both banks of the Meuse and gave orders for a barrage position to be established through Avocourt, Fort de Marre, Verdun's NE outskirts and Fort du Rozellier. The line Bras-Douaumont was divided into four sectors, each sector was entrusted to fresh French troops of the 20th "Iron" Corps. Their main job was to delay the German advance with counter-attacks.

On 29 February, the German attack was slowed down at the village of Douaumont by heavy snowfall and a tenacious defence by the French 33rd Infantry Regiment which had been commanded by Pétain himself in the years prior to the war. Captain Charles de Gaulle, the future Free French leader (World War II), and French President, was a company commander in this regiment and was taken prisoner near Douaumont during the battle. This slowdown gave the French time to bring up 90,000 men and 23,000 tons of ammunition from the railhead at Bar-le-Duc to Verdun. This was largely accomplished by uninterrupted, night-and-day trucking along a narrow departmental road: the so-called "Voie sacrée". The standard gauge railway line going through Verdun in peacetime had been interrupted since 1915.

As in so many previous offensives on the Western Front, the German assailants had lost effective artillery cover by advancing too fast in the early stages of the attack. With the battlefield turned into a sea of mud through continual shelling, it was more and more difficult for German artillery to follow forward in this very hilly terrain. German infantry's southward advance also brought it into range of French field artillery on the opposite side of the Meuse river. Each new advance to the south, towards the city of Verdun, became more and more costly than the previous ones as the attacking German Fifth Army units were cut down by Pétain's artillery massed on the opposite, or the west bank of the Meuse river. When the village of Douaumont was finally captured by German infantry on 2 March 1916, the Germans had suffered 2,000 casualties. Four German infantry regiments had been decimated.[9]

Unable to make any further progress against Verdun frontally, the Germans turned to the flanks, attacking on the west bank, or left bank, of the Meuse river at the hills of Le Mort Homme on 6 March and Côte (Hill) 304 on 20 March. The German artillery preparation and its follow up involved some 800 heavy guns which fired nearly 4 million shells and transformed the two hills into volcanoes of mud and rocks. The top of Côte 304 had gone down from 304 metres to 300 metres, as surveyed after the war. Mort Homme Hill sheltered active batteries of French field guns which had long hindered German progress towards Verdun on the right bank. They also provided commanding views of all the left bank battlefield.

After storming the Bois des Corbeaux, and then losing it to a determined French counter-attack, the Germans launched another assault on Le Mort Homme on 9 March and this time from the direction of Béthincourt to the northwest. They also seized the Bois des Corbeaux a second time, but at a crippling cost before they could finally occupy the crests of Le Mort Homme and Côte 304. During this successful advance, they had also captured the destroyed villages of Cumières and Chattancourt.

May–June 1916

During May 1916, the main event was the French failed attempt to reoccupy Fort Douaumont. The assault had been planned by recently promoted General Robert Nivelle and executed on a very narrow front under the direction of General Charles Mangin. It involved three infantry divisions supported by 300 guns ranging from the 75 mm field gun to heavy 6-inch (150 mm) and 12-inch (300 mm) howitzers. The assault began on 22 May after a massive artillery preparation. Three days later the French attempt had failed, although French infantry had occupied the superstructure of Fort Douaumont for over 12 hours. Mangin was blamed for that failure and refused to carry out another attempt. Higher up, Pétain also refused to support a renewed attempt to recapture Douaumont, invoking insufficient heavy artillery availability at the time.

Then, later in May 1916, the German attacks shifted from the left bank (Mort-Homme and Côte 304) and returned to the right bank, south of Fort Douaumont. They found a focus on Fort Vaux which was shelled continuously by the heaviest German siege guns. After a final assault initiated on 1 June by nearly 10,000 German shock troops, they occupied the top of the fort on 2 June. However, the underground casemates of Fort Vaux still remained under French control. Then close fighting proceeded underground for five days, barricade by barricade, in the narrow corridors of the fort. The French garrison of Fort Vaux, led by a Major Raynal, finally surrendered on 7 June when the defenders had run out of water. Up to this point, losses had been appalling on both sides. General Pétain had attempted to spare his troops by remaining on the defensive, but he had been relieved on 1 May from his Verdun command and promoted to lead the overall Centre Army Group which still included the Verdun sector. General Pétain had been replaced with the more attack-minded General Robert Nivelle, an artillery man by training and by previous command experiences.

June–July 1916

The German's next tactical move, on the right bank of the Meuse river, was to continue to press southward towards the city of Verdun. As a preliminary, on 21 June, German assault troops (60,000 men) took the redoubt of Thiaumont and the ruined village of Fleury. But just before the descent onto Verdun stood a final barrier they had to overcome: Fort Souville. It was a second line of fortification whose upper levels had already been reduced to rubble by German heavy shells, sparing only the fort's deepest underground corridors. To prepare for the assault on Souville, the Germans, beginning on 10 July, attempted to incapacitate French artillery with over 60,000 diphosgene gas shells (the so-called "Green Cross Gas"). This was largely ineffective since the French, quite fortuitously, had just been equipped with their latest type of gas mask (the M2 gas mask).

In the meantime, German heavy guns hammered Fort Souville and its approaches with more than 300,000 shells including some 500 14-inch shells aimed at the fort itself. However, when the time for the assault came, the path leading to Fort Souville had narrowed down and became too tightly packed with German infantry which came under devastating fire from French artillery barrages. What was left of the German assault troops (Bavarians and Alpen Korps) was further thinned out by French machine gunners who had emerged from the fort's ruins and taken positions on its superstructure. Fewer than a hundred German infantrymen managed somehow to escape their fire and made it to the top of the fort on 12 July. From that position, they could actually see the roofs of the city of Verdun and the spire of its cathedral. But being decimated by hand grenades and belatedly by a 75 mm artillery barrage falling on the fort, they had to retreat to their starting lines or choose to surrender. Thus, Fort Souville, on 12 July 1916 in the morning, became the historic high mark of the unsuccessful German offensive against Verdun. Fort Souville, the deeply scarred superstructure of which is only partially visible today because of large water-filled shell craters and dense vegetation, is one of the most horrifying and also one of the most hazardous sites of the old Verdun battlefield.

In the meantime, while Souville was under assault, the opening of the Battle of the Somme on 1 July 1916, had forced the Germans to withdraw some of their artillery from Verdun to counter the combined Anglo-French offensive to the north. The battle of the Somme was launched in part by the allies to try to take some of the pressure off the French at Verdun.

By late 1916, the German troops were exhausted, and Falkenhayn had been replaced as Chief of the General Staff by Paul von Hindenburg. Hindenburg's deputy, Chief Quartermaster-General Erich Ludendorff, soon acquired almost dictatorial power in Germany.

French counter-offensives in late 1916 and August 1917

The French launched a major counter-offensive to recapture Douaumont in October 1916. Its architect was General Nivelle, an experienced commander in the massive use of artillery. The preparation which lasted six days consummed 530,000 75 mm artillery shells plus 100,000 155mm shells, not counting the heavier calibers. The final assault on Fort Douaumont combined an infantry attack following behind a progressive "creeping" forward artillery barrage timed to keep the enemy machine gunners down. To soften up Douaumont before this assault, two French Saint-Chamond railway guns located eight miles to the southwest at Baleycourt had inflicted crushing blows onto the fort with 400 mm (16-inch) 1 ton shells. At least twenty of those 1 ton shells hit the fort, six of them penetrating down to the lowest levels before exploding. The Germans partly evacuated Douaumont which was then recaptured on 24 October by French marine infantry and colonials. On 2 November, the Germans evacuated Fort Vaux which had also come under fire from the 400 mm railway guns. A broader offensive, planned by General Nivelle and executed by General Mangin, began on 15 December and drove the Germans back close to their initial February starting lines. Within 36 hours the French had taken 11,387 prisoners, including 284 officers, and captured 115 artillery pieces. To some German senior officers who complained to Mangin about their lack of comfort in captivity he replied (translated from the French): "We do regret it, gentlemen, but then we did not expect so many of you". Unquestionably, German morale at Verdun had begun to deteriorate after the failure to seize Fort Souville and then later after the loss of Fort Douaumont.

A limited French offensive on the left bank in August 1917, planned by General Pétain and carried out with overwhelming heavy artillery, rapidly recaptured Mort-Homme Hill as well as Côte 304. Later on, during 1918 and until the Armistice, the Verdun Sector remained an active battle zone where the two adversaries never ceased to confront each other in life-wasting local actions. A certain discontent had begun to spread among the French combatants on the Verdun battlefield during the summer of 1916. The signs, intercepted in the soldier's mail and heard in the rest areas, progressed from a quiet weariness into open manifestations of contempt for the high command and the politicians. Furthermore, the departure of General Pétain from his Verdun command on 1 June 1916 and his replacement by General Nivelle had a negative impact on the soldiers' morale. Only ten days after Nivelle had replaced Pétain at the helm, two French lieutenants, Henri Herduin and Pierre Millant were summarily executed by firing squad, on 11 June 1916, in Fleury-devant-Douaumont. The executions were illegal since they had been carried out without proper court martial judgement but only with Nivelle's consent. Herduin and Millant had walked back from their positions, together with the few survivors of their company, as their relief was long overdue and they had run out of ammunition. Ten years later, in 1926, and after an inquiry that became a "cause célèbre", the late Lieutenant Herduin and Lieutenant Millant were totally exonerated, and their official military records expunged. However, and more generally, the horror of Verdun never left the battlefield until the Armistice of 11 November 1918 finally put an end to it. The last major combat in the Verdun sector took place during the Meuse-Argonne offensive, successfully carried out by the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) from 12 September to the Armistice.

French and German casualties

The Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary) were waging war on two fronts in 1916, in Russia and on the Western Front. Their strategy was to inflict more casualties on their adversaries than they themselves suffered. The German Army had achieved this goal in Russia during 1914 and 1915. Beyond this result, it also had to inflict casualties on the French Army that would weaken it to the point of collapse. In order to reach this objective, the French Army had to be drawn into a situation from which it could not escape for strategic and national pride reasons. The German Army also counted on their larger numbers of heavy and super heavy guns to deliver higher casualty counts than French artillery which relied upon the 75 mm field gun.

In reality, the German goal of inflicting disproportionate casualties on the French Army at Verdun was never achieved. The French Army's losses at Verdun were high, but only slightly higher than the German losses. General (later Marshal) Philippe Pétain was sparing of his troops and rotated them out after only 2–3 weeks in the front lines. Nevertheless, he managed to keep at least eleven French divisions (over 100,000 men) fully deployed on the Verdun battlefield at any given time. Thanks to Pétain's rotation system, 70% of the French Army went through "the wringer of Verdun", as opposed to only 25% of the German forces. General Pétain had always been a strong supporter of artillery firepower. His pre-war dictum: "le feu tue" or "firepower kills" was also the nub of his strategy at Verdun. By June 1916, French artillery at Verdun had grown to 2,708 guns, including 1,138 X 75 mm field guns which were highly effective in an anti-personnel role. To open his morning staff meetings, General Pétain was known to always ask the same question: "What is our artillery doing?"

French military casualties at Verdun, in 1916, are recorded as: 371,000 men including 60,000 killed, 101,000 missing and 210,000 wounded. Total German casualties at Verdun, between February and December 1916, are recorded as 337,000 men. The statistics also confirm that at least 70% of the Verdun casualties on both sides were the result of artillery fire. The shell consumption by French artillery at Verdun, between 21 February and 30 September at Verdun, totalled 23.5 million rounds. Most of them (16 million shells) were fired by the French 75 batteries which lined up about 1000 guns on the battlefield. German sources document that their own artillery, mostly heavy and super heavy, fired off over 21 million shells from February to September 1916 only.

Period photographs and current visitors to the Verdun battlefield testify to the huge numbers of shell craters that overlap each other endlessly over several hundred square miles. Forests planted in the 1930s have grown up and thus hide most of the hideous fields of the "Zone Rouge" (the "Red Zone") where so many men lost their lives or limbs. The battlefield is actually a vast graveyard since the mortal remains of over 100,000 missing combatants are still dispersed underground wherever they fell. To this day they are still being discovered by the French Forestry Service which turns them over to the Douaumont ossuary where they find a final resting place.

Significance

The Battle of Verdun—also known as the Mincing Machine of Verdun or Meuse Mill—became a symbol of French determination to hold the ground and then roll back the enemy at any human cost. However, it is quite clear that the French High Command had been caught unprepared by the assault on Verdun in February 1916. As time passed, Verdun became a battle of attrition where artillery continued to play the dominant role. A significant factor that helped even out the odds in favour of the French Army was their intensive use of trucking to keep troops and supplies coming onto the front lines. Furthermore, during the summer of 1916, a standard gauge railway bypass (the Nettancourt-Dugny line) was completed and took over from the truck traffic on the Voie sacrée. First, the intense trucking on the Voie sacrée and then later the opening of the Nettancourt-Dugny railway line, had not been anticipated by the German military planners.

The German General Staff had chosen Verdun as a strategic target, instead of Belfort, because the standard gauge railway lines going through Verdun in peacetime had been interrupted. One line coming from the south into Verdun had been severed at Saint-Mihiel by the German occupation of that town in 1914. The other railway line leading westward out of Verdun and onto Paris was under their direct observation and artillery fire at Aubreville. Thus, at the outset, the German planners saw Verdun for what it was: a salient cut off on three sides, a cul-de-sac without effective railway communications and thus a trap onto which they could strike a fatal blow against the French Army. What they did not anticipate was that, once the initial surprise had worn out, French logistics would improve with time and rob them of their initial advantage. It has often been remarked that Verdun was, in large part, a logistic victory of the French trucks over the German railways.

The perceived success of the fixed fortification system led to the adoption of the Maginot Line (Ligne Maginot) as the basic defensive system along the Franco-German border during the inter-war years. In reality, during the Battle of Verdun, French conventional field artillery massed in the open outnumbered the turreted guns in the Verdun forts by a factor of at least fifty to one. As a matter of fact, post-war statistics bear out that massed French field artillery plus several heavy railway guns inflicted over 70% of the casualties inflicted to the German assailants at Verdun. Infantry small arms and a few turreted guns in the forts account for most of the rest. Some twenty years later, the Maginot line suffered from the same conceptual flaw as the Verdun forts: too few turreted guns in relation to the enormous tonnage of concrete and steel that was needed to support these mostly underground installations. Nevertheless, Verdun remained a symbol of French determination for many years. At the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1953–54, General Christian de Castries remarked that the situation was " somewhat like Verdun."[11]

Further reading

- Brown, Malcolm Verdun 1916 Tempus Publishing, 1999, ISBN 0-7524-1774-6

- Clayton, Anthony. Paths of Glory – The French Army 1914–18., ISBN 0-304-36652-8

- Denizot, Alain, 1996, Verdun, 1914–1918. Nouvelles Editions Latines. Paris. ISBN 2-7233-0514-7. The most detailed and most complete facts, statistical figures and maps drawn from the original military archives covering the Battle of Verdun are found in this volume (in French). This is the publication of his Ph.D. Thesis at the University of Paris (Sorbonne).

- Foley, Robert. German Strategy and the Path to Verdun., Cambridge University Press 2004. ISBN 0-521-84193-3

- Holstein, Christina. Walking Verdun. Pen and Sword Battleground, 2009. ISBN 978-1-84415-867-6

- Horne, Alistair. The Price of Glory., ISBN 0-14-017041-3

- Keegan, John. The First World War., ISBN 0-375-70045-5

- Le Halle, Guy, 1998,Verdun, les Forts de la Victoire, CITEDIS, Paris. ISBN 2-911920-10-4 (in French). Contains highly detailed technical descriptions of all the Verdun region forts.

- Martin, William. Verdun 1916. London: Osprey Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1-85532-993-X

- Mosier, John. The Myth of the Great War., ISBN 0-06-008433-2

- Pétain, Marshal Henri Philippe Verdun (English translation) Elkin Mathews & Marrot, 1930

- Ousby, Ian. The Road to Verdun. ISBN 0-385-50393-8

References

- Dupuy, R. Ernest and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Harper's Encyclopedia of Military History, HarperCollins Publishers, 1993.

- Grant, R.G., Battle:A Visual Journey through 5,000 years of Combat, DK Publishing, 2005.

- Ground warfare: an international encyclopedia, Vol.1, Ed. Stanley Sandler, ABC-CLIO, 2002.

- Holger Afflerbach Falkenhayn. Politisches Denken und Handeln im Kaiserreich, München: Oldenbourg, 1994.

- Le Halle, Guy, 1998,Verdun. Les Forts de la Victoire, CITEDIS, Paris.

- MacKenzie, Donald A., The story of the Great War, Buck Press, 2009.

- The Encyclopedia Americana, Vol.28, J.B. Lyon Company, 1920.

- Total War: Combat and Mobilization on the Western Front, 1914–1918, Roger Chickering and Stig Foerster, eds., New York: Cambridge, 2000.

Notes

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana, Vol.28, (J.B. Lyon Company, 1920), 283.

- ^ MacKenzie, Donald A., The story of the Great War, (Buck Press, 2009), 142.

- ^ Dupuy, 4th Ed.,1052.

- ^ Grant, 276.

- ^ Dupuy, 4th Ed.,1052.

- ^ Grant, 276.

- ^ (Le Halle,1998)

- ^ Holger Afflerbach Falkenhayn. Politisches Denken und Handeln im Kaiserreich (München: Oldenbourg, 1994); "Planning Total War? Falkenhayn and the Battle of Verdun, 1916," in Great War, Total War: Combat and Mobilization on the Western Front, 1914–1918, Roger Chickering and Stig Foerster, eds. (New York: Cambridge, 2000)

- ^ a b c d e http://www.wereldoorlog1418.nl/battleverdun/index.htm#battle02

- ^ The Mammoth Book of Modern Battles - Verdun

- ^ Windrow, M. The Last Valley, (London, 2004), p. 499.

See also

- Émile Driant

- French villages destroyed in the First World War which were ruined during the Battle of Verdun, and six of which have not subsequently been rebuilt

- Douaumont ossuary

- Verdun Memorial

- Voie Sacrée

- Zone rouge (First World War)

- Rue Verdun, Beirut, Lebanon.

External links

La place forte de Verdun 1870–1918 sur www.fortiffsere.fr http://fortiffsere.fr/verdun/

- Verdun Page – English+German

- Info from firstworldwar.com

- Verdun book excerpt

- Dutch/Flemish WW1 Forum

- "Verdun – A Battle of the Great war".