Armero tragedy

The Armero tragedy (Spanish: Tragedia de Armero) was the major consequence of the November 13, 1985, eruption of Nevado del Ruiz in Tolima, Colombia. Pyroclastic flows melted the mountain's ice cap, sending four lahars (mudslides) down its slopes at 60 kilometers (37 mi) per hour. One covered the town of Armero, killing most of its population, more than 20,000 of its almost 29,000 inhabitants.[1] Deaths in other towns, particularly Chinchina, brought the overall death toll to 23,000. Footage and photos of Omayra Sánchez, a young victim of the tragedy, were published around the world.

This was the second-deadliest volcanic disaster of the 20th century, surpassed only by the 1902 eruption of Mount Pelée, and is the fourth-deadliest volcanic eruption in recorded history.

Geologists and other experts had warned authorities and media outlets about the danger over the weeks and days leading up to the eruption. On the day of the eruption, several evacuation attempts were made, but a severe storm restricted communications. Many victims stayed in their houses as they had been instructed, believing that the eruption had ended. The noise from the storm may have prevented many from hearing the noises from Ruiz.

Armero was the third-largest town in the Tolima Department after the Department capital, Ibagué, and the city of Espinal. The volcano had been dormant for 69 years before 1985.[2]

1985 activity

Precursor

In late 1984, geologists noticed that seismicity in the area had begun to increase.[3] Increased fumarole activity, deposition of sulfur on the summit of the volcano, and small phreatic eruptions alerted geologists to a possible eruption. These events were taking place when magma touched water, shooting steam high into the air.[3] In October 1985, activity began to decline, probably because the new magma had finished rising into Nevado del Ruiz's volcanic edifice (before September 1985).[3]

An Italian volcanological mission analyzed gas samples from fumaroles along the Arenas crater floor and found them to be a mixture of carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide, indicating a direct release of magma into the surface environment. Publishing a report for officials on October 22, 1985, the scientists determined that the risk of lahars was unusually high. To prepare for the eruption, the report gave several simple preparedness techniques to local authorities.[4]

In November 1985, volcanic activity once again increased[3] as magma neared the surface. Increasing quantities of gases rich in sulfur dioxide and elemental sulfur began to appear in the volcano. The water content of the fumaroles' gases decreased, and water springs in the vicinity of Nevado del Ruiz became enriched in magnesium, calcium and potassium, leached from the magma.[3] The thermodynamic equilibration (stationary heat energy) temperatures, corresponding to the chemical composition of the discharged gases, were from 200 °C (400 °F) to 600 °C (1,000 °F). The extensive degassing of the magma caused pressure to build up inside the volcano, which eventually resulted in the explosive eruption.[5]

Eruption

At 9:09 pm, on November 13, 1985,[6] Nevado del Ruiz erupted, ejecting dacitic tephra more than 30 kilometers (19 mi) into the atmosphere.[3] The total mass of the erupted material (including magma) was 35 million tonnes[3]—only 3% of the amount that erupted from Mount St. Helens in 1980.[7] The eruption reached a value of 3 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index.[8] The mass of the ejected sulfur dioxide was about 700,000 tonnes, or about 2% of the mass of the erupted solid material,[3] making the eruption atypically sulfur rich.[9]

The eruption produced pyroclastic flows that melted summit glaciers and snow, generating four thick lahars that raced down river valleys on the volcano's flanks,[10] destroying a small lake that was observed in Arenas' crater several months before the eruption.[3] Water in such volcanic lakes tends to be extremely salty, and may contain dissolved volcanic gases. The lake's hot, acidic water significantly accelerated the melting of the ice, an effect confirmed by the large amounts of sulfates and chlorides found in the lahar flow.[3]

The lahars, formed of water, ice, pumice, and other rocks,[10] mixed with clay as they traveled down the volcano's flanks.[11] They ran down the volcano's sides at an average speed of 60 km per hour, eroding soil, dislodging rock, and destroying vegetation. After descending thousands of meters down the side of the volcano, the lahars were directed into all of the six river valleys leading from the volcano, where they grew to almost four times their original volume. In the Gualí River, a lahar reached a maximum width of 50 meters (200 ft).[10] One of the lahars virtually erased the small town of Armero in Tolima Department, which lay in the Lagunilla River valley. Around one quarter of its 28,700 inhabitants survived.[10]

A second lahar, which descended through the valley of Chinchina River, killed about 1,800 people and destroyed about 400 homes in the town of Chinchina.[12] In total, over 23,000 people were killed, approximately 5,000 were injured,[10] and more than 5,000 homes were destroyed.[10] The Armero tragedy, as the event came to be known, was the second-deadliest volcanic disaster of the 20th century, surpassed only by the 1902 eruption of Mount Pelée,[13] and is the fourth-deadliest volcanic eruption in recorded history.[14] It is also the deadliest lahar,[15] and Colombia's worst natural disaster.[16]

Impact

The loss of life during the 1985 eruption was exacerbated by the lack of an accurate timeframe for the eruption, and the unwillingness of local authorities to take costly preventative measures without clear signs of imminent danger.[17] After black ash columns erupted from the volcano at approximately 3:00 pm local time, the local Civil Defense director was alerted to the situation. He contacted INGEOMINAS, who ruled to evacuate the area; he then was told to contact the Civil Defense director in Bogota and Tolima. Between 5:00 and 7:00 pm, the ash stopped falling, and local officials instructed people to "stay calm" and go inside. Around 5:00 pm an emergency committee meeting had begun, and when it ended at 7:00 pm, several members contacted the regional Red Cross of the intended evacuation efforts at Armero, Mariquita, and Honda. The Ibague Red Cross contacted Armero's officials and ordered an evacuation, which was not carried out because of electrical problems caused by a storm. The storm's heavy rain and constant thunder may have blotted out the noise of the volcano, and with no systematic warning efforts, the residents of Armero were completely unaware of the continuing activity at Ruiz. At 9:45 pm, after the volcano had already erupted, Civil Defense officials from Ibague and Murillo tried to warn Armero's officials, but could not make contact. Later they overheard conversations between individual officials of Armero and others; famously, a few heard the Mayor of Armero speaking on a ham radio, saying "that he did not think there was much danger", when he was overtaken by the lahar.[18]

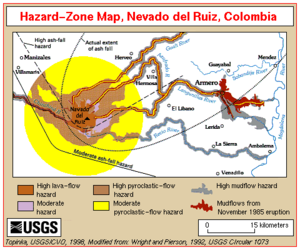

Because its last substantial eruption had occurred 140 years earlier, in 1845, it was difficult for many to accept the danger presented by the volcano; locals even called it the "Sleeping Lion".[19] Hazard maps showing that Armero would be completely flooded after an eruption were distributed more than a month before the eruption, but the Colombian Congress criticized the scientific and civil defense agencies for scaremongering.

Scientists reflecting later noticed that several long-period earthquakes (which begin strongly and then slowly die out) had occurred in the final hours before the eruption. Volcanologist Bernard Chouet said that, "the volcano was screaming 'I'm about to explode'", but the scientists who were studying the volcano at the time of the eruption were not able to read the signal.[20]

Relief efforts

The eruption occurred at the same time as the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, slightly reducing the amount of supplies that were sent. The US government spent over $1 million in aid, and US Ambassador to Colombia Charles S. Gillespie Jr. donated an initial $25,000 to Colombian disaster assistance institutions. The Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance of the US Agency for International Development (AID) additionally sent one member of the United States Geological Survey (USGS), along with an AID disaster-relief expert and 12 helicopters with support and medical personnel from Panama. The US subsequently sent further aircraft and supplies, including 500 tents, 2,250 blankets, and several tent repair kits. Twenty-four other nations contributed to the rescue and assistance of survivors. Ecuador supplied a mobile hospital, and Iceland's Red Cross sent $4,650. The French government sent their own medical supplies with 1,300 tents. Japan sent $1.25 million, along with eight doctors, nurses, and engineers, plus $50,000 to the United Nations for relief efforts.[21]

Because Armero's hospital was destroyed in the eruption, helicopters moved any survivors to nearby hospitals. Six local towns set up makeshift emergency relief clinics, consisting of treatment areas and shelters for the homeless. To help with the treatment, physicians and rescue teams came from all over the country.[22]

The eruption was used as an example for psychiatric recuperation after natural disasters by Robert Desjarlais and Leon Eisenberg in their work World Mental Health: Problems and Priorities in Low-Income Countries. The authors were concerned that only initial treatment for the survivors' trauma was conducted. Often survivors of natural disasters experience grief, loss, and "the daunting task of rebuilding their lives". One study showed that the victims of the eruption suffered from anxiety and depression, which can lead to alcohol abuse and marital problems amongst others.[22]

Aftermath

A lack of preparation for the disaster contributed to the high death toll. Armero had been built on old mudflows; authorities had ignored a hazard-zone map that showed the potential damage to the town if lahar were to avalanche down the mountain. Residents stayed inside their dwellings to avoid the falling ash, as local officials had instructed them to do, not thinking that they might be buried by the mudflows.[7]

The disaster gained major international notoriety due in part to a photograph taken by photographer Frank Fournier of a young girl named Omayra Sánchez, who was trapped beneath rubble for three days before she died.[23] Two photographers from the Miami Herald won a Pulitzer Prize for photography of the effects of the lahar.[24] Dr. Stanley Williams of Louisiana University said that following the eruption, "With the possible exception of Mount St. Helens in the state of Washington, no other volcano in the Western Hemisphere is being watched so elaborately."[25] In response to the eruption, the USGS Volcano Crisis Assistance Team was formed in 1986,[26] and the Volcano Disaster Assistance Program.[27] The volcano erupted several more times between 1985 and 1994.[28]

Preparedness

The volcano continues to pose a serious threat to nearby towns and villages. Of the threats, the one with the most potential for danger is small-volume eruptions, which can destabilize glaciers and trigger lahars.[29] Although much of the volcano's glacier mass has retreated, a significant volume of ice still sits atop Nevado del Ruiz and other volcanoes in the Ruiz–Tolima massif. A melting of just 10% of the ice would produce mudflows with a volume of up to 200 million cubic meters—similar to the mudflow that destroyed Armero in 1985.[15] In just hours, these lahars can travel up to 100 km along river valleys.[15] Estimates show that up to 500,000 people living in the Combeima, Chinchina, Coello-Toche, and Guali valleys are at risk, of whom 100,000 are considered to be at high risk.[29][a] Lahars poses a threat to the nearby towns of Honda, Mariquita, Ambalema, Chinchina, Herveo, Villa Hermosa, Salgar and La Dorada.[18] Although small eruptions are more likely, the two-million-year eruptive history of the Ruiz–Tolima massif includes numerous large eruptions, indicating that the threat of a large eruption cannot be ignored.[29] A large eruption would have more widespread effects, including the potential closure of Bogotá's airport due to ashfall.[30]

As the Armero tragedy was exacerbated by the lack of early warnings,[17] unwise land use,[31] and the unpreparedness of nearby communities,[17] the government of Colombia created a special program (Oficina Nacional para la Atencion de Desastres, 1987) to prevent such incidents in the future. All Colombian cities were directed to promote prevention planning to mitigate the consequences of natural disasters,[31] and evacuations caused by volcanic hazards have been carried out. About 2,300 people living along five nearby rivers were evacuated when Nevado del Ruiz erupted again in 1989.[32] When another Colombian volcano, the Nevado del Huila, erupted in April 2008, thousands of people were evacuated because volcanologists worried that the eruption could be another "Nevado del Ruiz".[33]

See also

Notes

- ^ Schuster, Robert L. and Highland, Lynn M. (2001). Socioeconomic and Environmental Impacts of Landslides in the Western Hemisphere, U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 01-0276. Also previously published in the Proceedings of the Third Panamerican Symposium on Landslides, July 29 to August 3, 2001, Cartagena, Colombia. Castaneda Martinez, Jorge E., and Olarte Montero, Juan, eds.,

- ^ "Nevado del Ruiz". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Naranjo, J.L. (1986). "Eruption of the Nevado del Ruiz Volcano, Colombia, On 13 November 1985: Tephra Fall and Lahars". Science. 233: 991–993. doi:10.1126/science.233.4767.961. PMID 17732038.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Barberi, F., Martini, M., and Rosi, M., F; Martini, M; Rosi, M (1990). "Nevado del Ruiz volcano (Colombia): pre-eruption observations and the 13 November 1985 catastrophic event". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 42 (1–2): 1–12. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(90)90066-O.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Giggenbach, Garcia, Rodriguez, Londoño, Rojas, Calvache, W.F., N., L., A., N., M.L.; Garciap, N; Londonoc, A; Rodriguezv, L; Rojasg, N; Calvachev, M (1990). "The chemistry of fumarolic vapor and thermal-spring discharges from the Nevado del Ruiz volcanic-magmatic-hydrothermal system, Colombia". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 42 (1–2): 13–39. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(90)90067-P.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mileti, Dennis S. (1991). The Eruption of Nevado Del Ruiz Volcano Colombia, South America, November 13, 1985. Washington, D.C.: Commission on Engineering and Technical Systems (National Academy Press). p. 13. ISBN 0309044774.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Wright, T.L. (1992). Living with Volcanoes: The U. S. Geological Survey's Volcano Hazards Program: USGS Circular 1073. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved December 13, 2008.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "Wright" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Watson, John. "Mount St. Helens – Comparisons With Other Eruptions". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ "TOMS measurement of the sulfur dioxide emitted during the 1985 Nevado del Ruiz eruptions". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 41 (1–4). Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research: 7–15. 1990. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(90)90081-P.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f "Deadly Lahars from Nevado del Ruiz, Colombia: November 13, 1985". United States Geological Survey. September 30, 1999. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ^ Lowe, Donald R. (1986). "Lahars initiated by the 13 November 1985 eruption of Nevado del Ruiz, Colombia". Nature. 324: 51–53. doi:10.1038/324051a0. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mileti, Dennis S. (1991). The Eruption of Nevado Del Ruiz Volcano Colombia, South America, November 13, 1985. Washington, D.C.: Commission on Engineering and Technical Systems (National Academy Press). p. 1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff. "Nevado del Ruiz – Facts and Figures". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

- ^ Topinka, Lyn. "Deadliest Volcanic Eruptions Since 1500 A.D." United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ a b c Huggel, Cristian (2007). "Review and reassessment of hazards owing to volcano–glacier interactions in Colombia" (pdf). Annals of Glaciology. 45: 128–136. doi:10.3189/172756407782282408.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff (November 14, 1995). "World News Briefs". CNN. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ a b c Fielding, Emma. "Volcano Hell Transcript". BBC. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

- ^ a b Mileti, Dennis S. (1991). The Eruption of Nevado Del Ruiz Volcano Colombia, South America, November 13, 1985. Washington, D.C.: Commission on Engineering and Technical Systems (National Academy Press). p. 80. ISBN 0309044774.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ BBC contributors (November 13, 1985). "BBC:On this day: November 13: 1985: Volcano kills thousands in Colombia". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ BBC contributors (August 27, 2003). "Signs of an eruption — A scientist has found a way to use earthquakes to predict when volcanoes will erupt". BBC. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Colombia's pleas for disaster aid draw worldwide response". Christian Science Monitor. November 19, 1985. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

- ^ a b Desjarlais and Eisenberg, p. 30.

- ^ Picture power: Tragedy of Omayra Sanchez BBC, September 30, 2005 - Retrieved: July 9, 2007

- ^ "Winners of Pulitzer Prizes in Journalism, Letters, and the Arts". New York Times. April 16, 1986. Retrieved 2008-11-26.

- ^ Sullivan, Walter (May 31, 1988). "At Ice-Clad Volcanoes, Vigils for Disaster". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ Russell-Robinson, Susan. "US team moves as Caribbean volcano dusts town with volcanic ash". USGS. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

- ^ Weiner, Tim (January 2, 2001). "Watchful Eyes On a Violent Giant". New York Times. Retrieved September 24, 2008.

- ^ "Nevado del Ruiz: Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2008-12-13.

- ^ a b c Thouret, Jean-Claude (1990). Stratigraphy and quaternary eruptive history of the Ruiz-Tolima volcanic massif, Colombia. Implications for assessement of volcanic hazards (PDF). Symposium international géodynamique andine: résumés des communications. Paris. pp. 391–393.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ McDowell, Bart (1986). "Eruption in Colombia". National Geographic: 640–653. Archived from the original on 2009-11-01.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Touret, Jean-Claude (1994). "Hazard Appraisal and Hazard-Zone Mapping of Flooding and Debris Flowage in the Rio Combeima Valley and Ibague City, Tolima Department, Colombia". GeoJournal. 34 (4): 407–413. doi:10.1007/BF00813136.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Associated Press (September 2, 1989). "Colombian Volcano Erupting". New York Times. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ Associated Press (April 15, 2008). "Colombian Volcano Erupts, Thousands Evacuated". Fox News. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

Sources

- Desjarlais, Robert (1996). World Mental Health: Problems and Priorities in Low-Income Countries. Oxford University Press US.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)