Thirteen Days (film)

| Thirteen Days | |

|---|---|

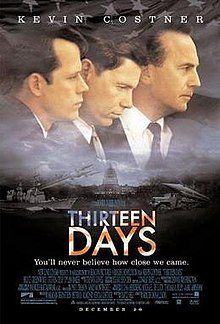

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Roger Donaldson |

| Written by | David Self |

| Produced by | Armyan Bernstein Thomas A. Bliss Kevin Costner et al |

| Starring | Kevin Costner Bruce Greenwood |

| Edited by | Conrad Buff |

| Music by | Trevor Jones |

| Distributed by | New Line Cinema |

Release date | December 25, 2000 |

Running time | 145 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $80 million |

| Box office | $33,094,473 |

Thirteen Days is a 2000 docudrama directed by Roger Donaldson about the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, seen from the perspective of the US political leadership.

While the movie carries the same name as the book Thirteen Days by former Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, it is in fact based on a different book, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis by Ernest May and Philip Zelikow. It is the second docudrama made about the crisis, the first being 1974's The Missiles of October, which was based on Kennedy's book. The 2000 film contains some newly declassified information not available to the earlier production, but takes greater dramatic license, particularly in its choice of Kenneth O'Donnell as protagonist.

Plot

In October, 1962, U-2 surveillance photos reveal that the Soviet Union is in the process of placing missiles carrying nuclear weapons in Cuba. These weapons have the capability of wiping out most of the Eastern and Southern United States in minutes if they become operational. President John F. Kennedy and his advisers must come up with a plan of action to prevent their activation. Kennedy is determined to show that the United States will not allow a missile threat in its virtual back yard. The Joint Chiefs of Staff advise immediate U.S. military strikes against the missile sites followed by an invasion of Cuba. However, Kennedy is reluctant to attack and invade because it would very likely cause the Soviets to invade Berlin. Kennedy sees an analogy to the events that started World War I, only this time nuclear weapons are involved. War appears to be almost inevitable.

The Kennedy administration tries to find a solution that will remove the missiles but avoid an act of war. They settle on a step less than a blockade, which is formally regarded as an act of war. They settle on what they publicly describe as a quarantine. They announce that the U.S. Naval forces will stop all ships entering Cuban waters and inspect them to verify they are not carrying weapons destined for Cuba. The Soviet Union sends mixed messages in response. John A. Scali, a reporter with ABC News, is contacted by Soviet emissary Aleksandr Fomin, and through this back-channel communication method the Soviets offer to remove the missiles in exchange for public assurances from the U.S. that it will never invade Cuba.

Khrushchev sends a long, apparently personally written message which is in the same tone as the informal communication from Fomin. This is followed by a second, more hard line cable in which the Soviets offer a deal involving U.S removal of its Jupiter missiles from Turkey. The Kennedy administration interprets the second as a response from the Politburo, and in a risky act, decides to ignore it and respond to the first message from Khrushchev. There are several mis-steps during the crisis: the defense readiness level of Strategic Air Command (SAC) is raised to DEFCON 2 (one step shy of maximum readiness for imminent war), without informing the President; and a routine test launch of a U.S. offensive missile is also carried out without the President's knowledge.

After much deliberation with the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, Kennedy secretly agrees to remove all Jupiter missiles from southern Italy and in Turkey, the latter on the border of the Soviet Union, in exchange for Khrushchev removing all missiles in Cuba. Off the shores of Cuba, the Soviet ships turn back from the quarantine lines. Secretary of State Dean Rusk says, "We're eyeball to eyeball and I think the other fellow just blinked."

Distribution

New Line Cinema was one of the production companies, alongside Kevin Costner's company Tig Productions and Armyan Bernstein's Beacon Communications. The film was given a limited release in late December 2000, but wide release did not occur until January 2001, with a staggered release to various countries throughout most of the year.

Reception

The film holds a 83% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes. The film was less successful financially, grossing $33,094,473 worldwide, against an $80 million budget.

Historical accuracy

The Missile Crisis was first publicly dramatized in the 1974 made-for-television play The Missiles of October. Thirteen Days portrays some incidents based on newly unclassified information not available in the earlier work, such as the shooting down of a U2 reconnaissance aircraft over Cuba during the crisis. In an interview provided on the DVD version, the director touts the meticulous attention to historical accuracy of Thirteen Days.

However, several still-living (as of the film's release) Kennedy administration officials and contemporary historians, including Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Special Counsel Ted Sorensen, and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, have criticized the film for the depiction of Special Assistant Kenneth O'Donnell as chief motivator of Kennedy and others during the crisis.[1] McNamara reacted in a PBS NewsHour interview:

"For God’s sakes, Kenny O’Donnell didn’t have any role whatsoever in the missile crisis; he was a political appointment secretary to the President; that’s absurd."[2]

According to McNamara, the duties performed by O'Donnell in the film are closer to the role Sorensen played during the actual crisis: "It was not Kenny O'Donnell who pulled us all together—it was Ted Sorensen."

The film has also been criticized for its anti-military bias in its portrayal of the Joint Chiefs, who in fact advocated a military response to take out the missiles, but are portrayed cartoonishly in their zeal, leading one political science professor to compare the film to the satirical Dr. Strangelove.[1]

The film was produced by Beacon pictures, owned by Kenny O'Donnell's son, Kevin M. O'Donnell, Who called his hands-on work on production of the film "his most significant achievement".

Cast

- Kevin Costner as Kenneth "Kenny" O'Donnell

- Bruce Greenwood as President John F. Kennedy

- Stephanie Romanov as First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy

- Steven Culp as Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy

- Dylan Baker as Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara

- Lucinda Jenney as Helen O'Donnell, wife of Kenneth "Kenny" O'Donnell

- Michael Fairman as United States Ambassador to the UN, Adlai Stevenson

- Bill Smitrovich as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Maxwell Taylor

- Frank Wood as National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy

- Ed Lauter as Deputy Director of the CIA, Lt. Gen. Marshall Carter

- Kevin Conway as Chief of Staff of the USAF Gen. Curtis LeMay

- Tim Kelleher as Ted Sorensen

- Len Cariou as Dean Acheson

- Chip Esten as Maj. Rudolf Anderson

- Olek Krupa as Soviet Foreign Minister, Andrei Gromyko

- Elya Baskin as Anatoly Dobrynin

- Jack McGee as Richard J. Daley

- Tom Everett as Walter Sheridan

- Oleg Vidov as Valerian Zorin

- Alex Veadov as Radio Room Operator #3

- Henry Strozier as Dean Rusk

- Walter Adrian as Vice-President Lyndon Johnson

- Christopher Lawford as Commander William Ecker (Lawford happens to be President Kennedy's nephew.)

- Madison Mason as Admiral George Whelan Anderson, Jr.

- Kelly Connell as Press Secretary Pierre Salinger

- Peter White as Director of Central Intelligence, John McCone

- Boris Lee Krutonog as Aleksandr Fomin

See also

- The Missiles of October, TV film portraying the crisis

- Thirteen Days (book), Robert Kennedy's posthumous memoirs of the crisis

References

- ^ a b Nelson, Michael, Political Science Professor, Rhodes College (February 2, 2001). "'Thirteen Days' Doesn't Add Up". The Chronicle Review. Chronicle of Higher Education: B15. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.pbs.org/newshour/forum/february01/thirteendays3.html

External links

- Thirteen Days at IMDb

- Thirteen Days at Rotten Tomatoes

- Thirteen Days at Box Office Mojo

- Thirteen Days in 145 minutes – commentary by Ernest R. May, Harvard professor who wrote the book on which it was based, on the accuracy of the movie

- White House Museum - How accurate was the movie recreation of the architecture and floor plan of the actual White House (review)

- 2000 films

- Cold War films

- American drama films

- 2000s drama films

- Historical films

- Films based on non-fiction books

- Films about Presidents of the United States

- Films set in the 1960s

- Films set in Florida

- Films set in Connecticut

- Films set in Washington, D.C.

- Films shot in Washington, D.C.

- Films set in Cuba

- Films based on actual events

- Political thriller films

- Films directed by Roger Donaldson

- Films shot in the Philippines