Casino Royale (novel)

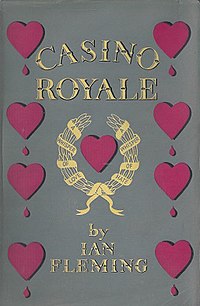

First edition cover - published by Jonathan Cape. | |

| Author | Ian Fleming |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Ian Fleming (devised) |

| Language | English |

| Series | James Bond |

| Genre | Spy novel |

| Publisher | Jonathan Cape |

Publication date | 13 April 1953 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 213 |

| ISBN | NA Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

| Followed by | Live and Let Die |

Casino Royale by Ian Fleming is the first James Bond novel. It would eventually pave the way for eleven other novels by Fleming himself, in addition to two short story collections, followed by many 'continuation' Bond novels by other authors.

Since first publication on April 13, 1953, by Jonathan Cape, Casino Royale has been adapted for the screen three times: (i) the Climax! CBS television episode with Barry Nelson as CIA agent "Jimmy Bond", 1954, (ii) a spoof with David Niven as "Sir James Bond" in 1967, and (iii) the twenty-first official film in the EON Productions film series with Daniel Craig as James Bond, released November 17, 2006.

The novel

Release and reception

Casino Royale was first released on 13 April 1953, in a United Kingdom hardcover edition by publishers Jonathan Cape.[1] The first paperback edition of Casino Royale in the United States was re-titled by publisher American Popular Library in 1955 (this followed a hardcover edition with the original title). Fleming's suggestions for a new title, The Double-O Agent and The Deadly Gamble, were disregarded in favour of You Asked For It. The novel was subtitled "Casino Royale" and made reference to secret agent 007 as "Jimmy Bond" on the back cover. After 1960, the original title Casino Royale replaced You Asked For It for all further paperback editions in the United States.

In 1954, Anthony Boucher reviewed the book for The New York Times, commenting that the book, although about a British Secret Service operative, belongs "pretty much to the private-eye school" of fiction. He praised the first part, saying that

- Fleming, in a style suggesting a more literate version of Cheyney's "Dark" series, manages to make baccarat clear even to one who's never played it and produced as exciting a gambling sequence as I've ever read. But then he decides to pad out the book to novel length and leads the weary reader through a set of tough clichés to an ending which surprises nobody save Operative 007. You should certainly begin this book; but you might as well stop when the baccarat game is over.[2]

Plot

Monsieur Le Chiffre ("the cypher"), the treasurer of a Soviet-backed trade union in the Alsace-Lorraine region of France, is running a baccarat game in the casino at Royale-les-Eaux, France, in order to recover union money he lost in a failed chain of brothels.

Expert baccarat player James Bond (British secret agent 007) is assigned to defeat Le Chiffre, in the hope that his gambling debts will provoke Soviet espionage agency SMERSH to kill him. Bond is provided an assistant, the beautiful but emotionally unstable Vesper Lynd, who becomes his lover. After hours of intense play Le Chiffre bankrupts Bond, but CIA agent Felix Leiter provides him with enough money to continue playing and leave Le Chiffre broke. Soon after, Le Chiffre abducts Vesper and uses her to lure Bond into a near-fatal car chase, which results in Bond's capture. Le Chiffre tortures Bond. However, when it becomes clear to Le Chiffre that Bond will not tell him where the money is, he threatens to castrate him. Seconds later a SMERSH agent assassinates Le Chiffre for his betrayal, shooting him through the head with a pistol. Unintentionally, the SMERSH assassin (whose organisation becomes the hero's bitter nemesis in later adventures) saves the captive Bond, saying: "I have no orders to kill you" — yet cuts the Cyrillic letter "Ш" (шпион, shpion, spy) in the back of Bond's left hand, "for future reference."

Bond spends three weeks in hospital recovering from his torture at the hands of Le Chiffre, expressing intent to resign from the secret service, and spends his convalescence with Vesper Lynd. After his recuperation he becomes suspicious of her because of the combination of apparent dishonesty and her terror of a man with an eye patch called Gettler. Believing that Gettler is a SMERSH assassin sent to kill her and Bond for her disobedience, Vesper commits suicide by an overdose of sleeping pills, leaving Bond an explanatory note where it is revealed that she is a Soviet double agent who was ordered to ensure Bond did not escape Le Chiffre. Her betrayal inspires him to remain in service; he tersely reports to HQ: "The bitch is dead now."

Story inspirations

It has been claimed that Fleming based Lynd on Christine Granville/Krystyna Skarbek.[3] Fleming stated that Casino Royale was inspired by certain incidents that took place during his career at the Naval Intelligence Division of the Admiralty. The first, and the basis for the novel, was a trip to Lisbon that Fleming and the Director of Naval Intelligence, Admiral Godfrey, took during World War II en route to the United States. While there, they went to the Estoril Casino in Estoril, which (due to the neutral status of Portugal) had a number of spies of warring regimes present. Fleming claimed that while there he was cleaned out by a "chief German agent" at a table playing chemin de fer. Admiral Godfrey tells a different story: Fleming only played Portuguese businessmen and that afterwards Fleming had fantasised about there being German agents and the excitement of cleaning them. His references to 'Red Indians' (four times, twice on last page) comes from Fleming's own 30 Assault Unit, which he nicknamed his own 'Red Indians'.

The failed assassination attempt on Bond while at Royale-Les-Eaux is also claimed by Fleming to be inspired by a real event. The inspiration comes from a failed assassination on Franz von Papen who was a Vice-Chancellor and Ambassador under Adolf Hitler. Both Papen and Bond survive their assassination attempts, carried out by Bulgarians, due to a tree that protects them both from a bomb blast.

Fleming wrote "Casino Royale" in Jamaica in 1952, two months before his wedding to pregnant girlfriend, Ann Charteris. There is speculation that he wrote the "ultimate spy novel" about giving up things in life, such as giving up bachelorhood for marriage.[4]

The city of Royale-les-Eaux and its casino are inspired by Le Touquet-Paris-Plage or by Deauville, where Fleming used to play as a young man.[5]

Comic strip adaptation

Casino Royale was the first James Bond novel to be adapted as a daily comic strip which was published in the British Daily Express newspaper, and syndicated worldwide. It ran from July 7, 1958 to December 13, 1958, and was written by Anthony Hern and illustrated by John McLusky; the strip was reprinted by Titan Books in the early 1990s and again in 2005; the 2005 collection, titled Casino Royale, also includes the comic strip adaptations of Live and Let Die and Moonraker.

To aid the Daily Express in illustrating James Bond, Ian Fleming commissioned an artist to create a sketch of what he believed James Bond to look like. The illustrater, John McLusky, however, felt that Fleming's 007 looked too "outdated" and "pre-war" and thus changed Bond to give him a more masculine look.

Publication history

First published in April 1953, Jonathan Cape has reported that of the 4,728 copies of Casino Royale that were printed, less than half of those were actually sold commercially; the rest were given to public libraries. In 2006, first editions of the book were selling for $30,000 to $60,000 from antiquarian booksellers. A second printing was published by Cape in May 1953 and a third in May 1954 using the same cover. Further printings used a different cover. The first edition’s cover was devised by Ian Fleming and executed by Kenneth Lewis; the motif used on the cover—of blood dripping from a heart—would be included in the opening credits of the 2006 film. Fleming also devised the cover for the first editions of Live and Let Die (1954) and Moonraker (1955). When the book came to the UK in paperback form in 1955, readers were given their first glimpse of an image of secret agent James Bond on the book jacket. The image of Bond was based on a photograph of American actor Richard Conte, who would become known for roles in films such as Ocean's Eleven (1960) and The Godfather (1972).

The following is a list of English language editions of Casino Royale;

- Casino Royale (1953 first edition)

- Publisher: Jonathan Cape

- Hardcover

- United Kingdom

- Casino Royale (1954)

- Publisher: Macmillan

- Hardcover

- United States

- You Asked For It (1955)

- Publisher: Popular Library

- Paperback

- US

- Casino Royale (1955)

- Pan Books

- Paperback

- UK

- Casino Royale (1960)

- Publisher: Signet Books

- Paperback

- US

- Casino Royale (1964)

- Publisher: Pan Books

- Paperback

- UK

- Casino Royale (1971)

- Publisher: Bantam Books

- Paperback

- US

- Casino Royale (1978)

- Publisher: Granada

- Paperback

- UK

- Casino Royale (1979)

- Publisher: Chivers Press

- Hardcover

- UK

- Large print edition

- Casino Royale (1980)

- Publisher: Jove Books

- Paperback

- US

- Casino Royale (1982)

- Publisher: Berkeley Books

- Paperback

- US

- Casino Royale (1987)

- Publisher: Charter Books

- Paperback

- US

- Casino Royale (1987)

- Publisher: Berkeley Books

- Paperback

- US

- Casino Royale (1988)

- Publisher: Coronet

- Paperback

- UK

- Casino Royale (2002)

- Publisher: Penguin Books

- Paperback

- US

- Casino Royale (2002)

- Publisher: Penguin Books

- Paperback

- UK

- Casino Royale, Live and Let Die, Moonraker (2003) [Omnibus volume][6]

- Publisher: Penguin Modern Classics

- Paperback

- UK

- Casino Royale (2004)

- Publisher: Penguin Modern Classics

- Paperback

- UK

- Casino Royale (2006)

- Publisher: Penguin Books

- Paperback

- UK

- Casino Royale (2006)

- Publisher: Penguin Books

- Paperback

- UK

- Casino Royale (2008)

- Publisher: Penguin 007

- Hardcover

- UK

After 2002, all English language editions of Casino Royale have been published by Penguin Books, or an imprint of penguin. [7]

Adaptations

1954 television episode

In 1954, producer and director Gregory Ratoff of CBS paid Ian Fleming $1,000 to adapt Casino Royale into a one-hour television adventure as part of their Climax! series. The episode aired on October 21, 1954 and starred Barry Nelson as secret agent "Card Sense" James 'Jimmy' Bond and Peter Lorre as Le Chiffre.

A brief tutorial on Baccarat is given at the beginning of the show, to enable viewers to understand a game which was not popular in America at the time.

For this Americanised version of the story, Bond is an American agent, described as working for "Combined Intelligence", while the character Felix Leiter from the original novel became French, was renamed "Clarence Leiter," (listed in the credits to the episode as Clarence Letter) and was an agent for Station S, while being a combination of Leiter and René Mathis. The name "Mathis" was given to the leading lady, who is named Valérie Mathis, instead of Vesper Lynd.

In this adaptation, Le Chiffre is highly placed in the French Socialists, and has gambled away 80,000 francs which belonged to the Soviets. He desperately hopes to win it all back, again at the Baccarat table.

Another change from the novel is that the extra 35,000 francs given Bond after he goes broke come from Mathis, one of Bond's former lovers who turns out to be a French intelligence agent.

This was the first screen adaptation of a James Bond novel. When MGM eventually obtained the rights to the 1967 film version of Casino Royale, it also received the rights to this television episode, which is included in the Special Features of the DVD release of the film.

Howard Hawks film

According to the biography Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood, by Todd McCarthy, the director of His Girl Friday considered filming a version of Casino Royale in 1962, possibly starring Cary Grant as James Bond, but, ultimately, chose not to. There is a webpage that speculates on what a Howard Hawks Bond film might have been like.[8]

Casino Royale (1967)

In 1955, Ian Fleming sold the film rights of Casino Royale to producers Michael Garrison (later creator of The Wild Wild West) and Gregory Ratoff for $6,000. Ratoff eventually tried to sell the idea of a James Bond series to 20th Century Fox but was turned down. In conjunction with Michael Garrison, Ratoff's widow sold the film rights to producer Charles K. Feldman after Ratoff's death. With the success of the official James Bond film series in the early 1960s, Feldman went to producers Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman with a proposition to produce a serious film version starring Sean Connery as agent 007, but was turned down after their discontent on a joint production with Kevin McClory on Thunderball. Like McClory's later 1983 production of Never Say Never Again, Feldman started his own production and first approached Connery who was in the heat of frustration playing the role. Connery offered his acceptance to do the film under a $1 million dollar salary (a salary Connery eventually received to return for 1971's Diamonds Are Forever and an even larger salary on Never Say Never Again), of which Feldman disapproved. Coming off the success of the comedy What’s New, Pussycat?, Feldman decided the best way to profit from the film rights was to make a satirical version. Feldman's satire was produced and released in 1967 by Columbia Pictures. Burt Bacharach wrote and arranged the soundtrack, which had appearances by Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass and Dusty Springfield.

The film was originally going to centre on the character of Evelyn Tremble (played by Peter Sellers) and his impersonation of James Bond. However, Sellers expressed increasing discontent when the film became focused on a comedy and not just the original serious treatment, which he felt his performance was suited for exclusively. This led to Sellers walking off the picture and Feldman's inability to continue production; firing the actor. Feldman later turned to one of the original choices to play James Bond before Sean Connery, actor David Niven, to shape his new scenes around what Peter Sellers/Ursula Andress segments could be used. Despite Feldman having on board what Bond film alumni screenwriter Richard Maibaum referred to in a 1987 interview as Fleming's main inspiration for Bond, the satire continued due to the absence of having Connery on board for a Bond film. After this film's budget had ballooned from its original $6 million dollar budget to $12 million, Feldman reportedly told Connery at a later Hollywood party that it would have been cheaper to have paid him his $1 million fee on only a serious version of the Casino Royale material.

The unproduced Raymond Benson stage play

In 1985, Raymond Benson adapted Fleming's novel into a stage play, although the play was never produced. The play was submitted to a British agent who recommended that it not be produced. In an interview Benson stated,

- "She was very elderly and in my opinion she just didn't get it. She recommended that the play not be produced. After further thought, Glidrose shelved it with the ultimate decision that a James Bond stage play simply wouldn't work. The films had Bond in a monopoly and there was no way a play could compete. I disagreed, but it was their property."[9] — Raymond Benson

In 1996, Benson went on to become the third continuation author of the James Bond novels (not counting John Pearson who did not write original novels in the oeuvre). In total, Benson wrote six novels, three novelisations, and three short stories before retiring from the job in 2002.

Casino Royale (2006)

In the 1990s, Sony Pictures Entertainment (which had incorporated Columbia Pictures) decided to make its own serious adaptation of Casino Royale and had also announced plans to produce its own rival Bond series, but these plans, in addition to Kevin McClory's plans for a second reconfiguration of Thunderball (the first being Never Say Never Again) were laid to rest when Sony settled a legal action with MGM/UA in 1999 giving up any rights to the James Bond character. Included in the settlement Sony traded the rights to Casino Royale for MGM's partial-rights to Spider-Man. The distribution rights to Never Say Never Again were previously acquired by MGM from Warner Bros. in 1997. Kevin McClory claimed until his death in November 2006 to own the film rights to Thunderball, but a court that heard the Sony/MGM case held that his rights had expired.

After MGM's acquisition of the film rights to Casino Royale there was speculation that an official version would be produced. In 2004, a Sony/Comcast consortium acquired MGM, and consequently, became co-owner of the Bond film series rights. Soon after, in 2005, it was announced by EON Productions that their next James Bond adventure would in fact be Casino Royale, to be directed by GoldenEye director Martin Campbell.

On October 14, 2005 during a news conference by EON Productions and Sony Pictures Entertainment it was announced that English actor Daniel Craig would play James Bond. Taking over from Pierce Brosnan, it was Craig's first appearance as the British secret agent. He is supported in the film by Eva Green as Vesper Lynd and Mads Mikkelsen as Le Chiffre. Judi Dench also returns for her fifth Bond film as Bond's superior, M. The film is a reboot, showing Bond at the beginning of his career as a 00-agent.

The film overall stays true to the original novel with most of the changes being adaptations to the changing times (such as Le Chiffre working for terrorists instead of Russians and the big stakes game at the casino is Texas Hold 'Em rather than Baccarat) and the circumstances and motive for Vesper's death are altered considerably. The film was first released on November 16, 2006, and on DVD and Blu-ray Disc March 13, 2007.

Cultural references

- The Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode “Our Man Bashir” has clear allusions to Casino Royale, including a British secret agent playing a game of baccarat against a villain at a French casino.

- In Wu Ming’s novel 54 (pub. 2003), Cary Grant goes on a secret mission on behalf of MI6. In the English countryside he stumbles upon a copy of Casino Royale and starts to read it. Grant’s harsh judgement on both the plot and the James Bond character is one of the comedic elements in the novel. He ends up discussing the book’s “incoherence” with British secret agents with his friend David Niven, who short-sightedly comments: “They’ll never make a film out of that!”. This reference has a double significance, as Grant (as noted above) was one of the first actors considered to play James Bond, while Niven portrayed the character in the 1967 film adaptation of the book (see above).

- In Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me, Austin can be seen parading around naked after his wife dies. In one of the parts of the hotel, a sign can be seen with the words Casino Royale, obviously a reference to Fleming's book.

References

- ^ "Universal Exports-Casino Royale". Retrieved 2006-03-04.

- ^ Boucher, Anthony (1954), "Criminals at Large," The New York Times, April 25, 1954, p. BR27

- ^ McCormick, Donald (1993). The Life of Ian Fleming. Peter Owen Publishers. p. 151.

- ^ Chancellor, Henry (2005). James Bond: The Man and His World. John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-6815-3.

- ^ Perfect break: Le Touquet The Daily Telegraph

- ^ http://www.iblist.com/book63018.htm

- ^ http://www.iblist.com/book4779.htm

- ^ Koenig, William (1998). "Howard Hawks' CASINO ROYALE". Retrieved 2006-03-04.

- ^ "Casino Royale The 'Lost' Stage Play". Retrieved August 6, 2005.

External links

- Climax! (1954) at IMDb - original broadcast of the TV version

- Casino Royale (1967) at IMDb

- Casino Royale (2006) at IMDb

- Casino Royale (1967) at Rotten Tomatoes

- Casino Royale (2006) at Rotten Tomatoes

- A travelogue of Fleming's French in Casino Royale

- 30 Commando Assault Unit - Ian Fleming's 'Red Indians' - Literary James Bond's wartime unit

See also

- James Bond - main article