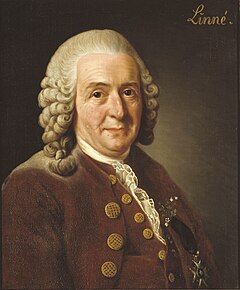

Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (Carl von Linné) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 23, 1707[a 1] Råshult, Stenbrohult parish (now within Älmhult Municipality), Sweden |

| Died | January 10, 1778 (aged 70) Hammarby (estate), Danmark parish (outside Uppsala), Sweden |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Alma mater | Lund University Uppsala University University of Harderwijk |

| Known for | Taxonomy Ecology Botany |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Botany Biology Zoology |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | L. |

| Signature | |

| Notes | |

Carl Linnaeus (sometimes confused with his less well known son, Carolus Linnaeus the Younger L.f.) [a 2] (Swedish original name Carl Linnæus, also Carl Nilsson Linnæus, Latinized as Carolus Linnæus,[a 3] also known after his ennoblement as , Latinized as Carolus a Linné, 23 May[a 1] 1707 – 10 January 1778) was a Swedish botanist, physician, and zoologist, who laid the foundations for the modern scheme of binomial nomenclature. He is known as the father of modern taxonomy, and is also considered one of the fathers of modern ecology.

Linnaeus was born in the countryside of Småland, in southern Sweden. Linnaeus got most of his higher education at Uppsala University and began giving lectures in botany there in 1730. He lived abroad between 1735–1738, where he studied and also published a first edition of his Systema Naturae in the Netherlands. He then returned to Sweden where he became professor of botany at Uppsala. In the 1740s, he was sent on several journeys through Sweden to find and classify plants and animals. In the 1750s and 60s, he continued to collect and classify animals, plants, and minerals, and published several volumes. At the time of his death, he was renowned as one of the most acclaimed scientists in Europe.

The Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau sent him the message: "Tell him I know no greater man on earth."[1] The German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote: "With the exception of Shakespeare and Spinoza, I know no one among the no longer living who has influenced me more strongly."[1] Swedish author August Strindberg wrote: "Linnaeus was in reality a poet who happened to become a naturalist".[2] Among other compliments, Linnaeus has been called "Princeps botanicorum" ("Prince of Botanists"), "The Pliny of the North" and "The Second Adam".[3]

In botany, the author abbreviation used to indicate Linnaeus as the authority for species names is simply L.[4]

In 1959 Carl Linnaeus was designated as lectotype for Homo sapiens,[5] which means that following the nomenclatural rules Homo sapiens was validly defined as the animal species to which Linnaeus belonged.

Biography

Early life

Childhood

Carl Linnaeus was born in Råshult, Småland, Sweden on 23 May 1707. He was the first child of Nils Ingemarsson Linnaeus and Christina Brodersonia; His father was the first in his ancestry to adopt a permanent last name; before that, ancestors had used the patronymic naming system of Scandinavian countries. His father adopted the Latin-form name Linnæus after a giant linden tree on the family homestead. This name was spelled with the æ ligature, which was also used by his son Carl in his handwritten documents and publications.

Nils was from a long line of peasants and priests. Nils was an amateur botanist, a Lutheran minister, and the curate of the small village of Stenbrohult in Småland. Christina was the daughter of the rector of Stenbrohult, Samuel Brodersonius. She subsequently gave birth to three daughters and another son, Samuel (who would eventually succeed their father as rector of Stenbrohult and write a manual on beekeeping).[6][7][8] A year after Linnaeus' birth his grandfather Samuel Brodersonius died, and his father Nils became the rector of Stenbrohult. Thus Linnaeus and his parents could move into the rectory instead of the curate's house where they had lived before.[9][10]

Even in his early years Linnaeus seemed to have a liking for plants, flowers in particular. Whenever he was upset he was given a flower which immediately calmed him. Nils spent much time in his garden and often showed flowers to Linnaeus and told him their names. Soon Linnaeus was given his own patch of earth in his father's garden where he could grow plants.[11]

Early education

His father began teaching Linnaeus Latin, religion, and geography at an early age; one account says that due to much use of Latin for household conversation he learned Latin before he learned Swedish. When Linnaeus was seven Nils considered it better for him to have a tutor. His parents picked Johan Telander, a son of a local yeoman. Telander was not appreciated by Linnaeus, who later wrote in his autobiography that Telander "was better calculated to extinguish a child's talents than develop them".[12] Two years after his tutoring had begun, in 1717, he was instead sent to the Lower Grammar School at Växjö.[13] Linnaeus rarely studied, instead he often went to the countryside to look for plants. Nevertheless Linnaeus managed to reach the last year of the Lower School when he was fifteen. This year was taught by the headmaster, Daniel Lannerus who was interested in botany. Lannerus noticed Linnaeus' interest in botany and gave him the run of his garden. He also introduced him to Johan Rothman who was the state doctor of Småland and teacher at Växjö Gymnasium. Rothman, being a doctor and thus at that time also a botanist, widened Linnaeus' interest in botany and helped him develop an interest in medicine.[14][15]

After having spent the last seven years in a grammar school Linnaeus entered the Växjö Gymnasium in 1724 . At the gymnasium he studied mainly Greek, Hebrew, theology and mathematics; a curriculum designed for someone who intended on a future as a priest.[16][17] In the last year at the gymnasium Linnaeus' father Nils visited to ask the professors at the gymnasium how Linnaeus' studies were progressing; to his dismay most of them told him that Linnaeus would never become a scholar. However, Rothman believed otherwise and suggested that Linnaeus could have a future in medicine. Rothman also offered that he would give Linnaeus a home in Växjö and teach him physiology and botany. Nils gratefully accepted this offer.[18][19]

University

Lund

Rothman showed Linnaeus that botany was a serious subject and not only a simple hobby. He taught Linnaeus to classify plants according to Tournefort's system. Linnaeus was also taught about sexuality of plants according to Sébastien Vaillant.[18] In 1727 Linnaeus, now 21, enrolled in Lund University in Skåne.[20][21] Linnaeus was offered tutoring and lodging by the local doctor Kilian Stobaeus. There he could use the doctor's library, including many books about botany, and was given free admission to the doctor's lectures.[22][23] In his free time Linnaeus explored the flora of Skåne together with students sharing the same interests.[24]

Uppsala

In August 1728 Linnaeus decided to attend Uppsala University on the advice of Rothman, who believed it would be a better choice if Linnaeus wanted to study both medicine and botany. Rothman based this recommendation on the two professors who taught at medical faculty at Uppsala: Olof Rudbeck the Younger and Lars Roberg. Both Rudbeck and Roberg had undoubtedly been good professors once but at that time they were old and not interested in teaching anymore. Rudbeck for example no longer gave public lectures himself, letting a less able person stand in for him. Thus the botany, zoology, pharmacology and anatomy lectures were not in their best state.[25] In Uppsala Linnaeus met a new benefactor, Olof Celsius. Celsius was a professor of Theology and an amateur botanist.[26] He received Linnaeus into his home and allowed him use of his library which was one of the richest botanical libraries in Sweden.[27]

In 1729 Linnaeus wrote a thesis, Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum on plant sexuality. This attracted the attention of Olof Rudbeck; in May 1730 he selected Linnaeus to begin giving lectures at the University even though Linnaeus was only a second year student. The lectures were very popular and Linnaeus could often find himself addressing an audience of 300 persons.[28] In June Linnaeus moved from Celsius' house into Rudbeck's house to become the tutor of the three youngest of his 24 children. His friendship with Celsius did not wane; they continued to go on botanical expeditions.[29] During that winter Linnaeus began doubting Tournefort's system of classification and decided to create one of his own. His plan was to divide the plants by the number of stamens and pistils. He began writing several books which would later result in, for example, Genera Plantarum and Critica Botanica. He also produced a book concerning the plants grown in Uppsala Botanical Garden, Adonis Uplandicus.[30]

Rudbeck's former assistant Nils Rosén returned to the University in March 1731 with a degree in medicine. Rosén started giving anatomy lectures and tried to take over Linnaeus' lectures in botany, an attempt stopped by Rudbeck. Until December Rosén gave Linnaeus private tutoring in medicine. In December Linnaeus had a "disagreement" with Rudbeck's wife and had to move out of Rudbeck's house; his relationship with Rudbeck went seemingly unharmed. That Christmas Linnaeus returned home to Stenbrohult to visit his parents for the first time in about three years. His mother's feelings for him had grown cold since he had chosen not to become a priest but when she heard that he was teaching at the University she was pleased.[30][31]

Expedition to Lapland

During a visit with his parents Linnaeus told them about his plan to travel to Lapland, a journey which Rudbeck had taken once in 1695, but the results of which had been lost in a 1702 fire. Linnaeus' hope was to find new plants, animals and possibly valuable minerals. He was also curious of the customs of the native Sami people, reindeer-herding nomads who wandered Scandinavia's vast tundras. In April 1732 Linnaeus was awarded a grant from the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala for his journey.[32][33]

Linnaeus began his expedition on 22 May; he travelled on foot and horse, bringing with him his journal, botanical and ornithological manuscripts and sheets of paper for pressing plants. It took him 11 days to reach his first destination, Umeå, sometimes dismounting on the way to examine a flower or rock.[34] He was particularly interested in mosses and lichens, the latter a main part of the diet of the reindeer, a common animal in Lapland.[35] Next, he reached Gävle where he found great quantities of Campanula serpyllifolia (later known as Linnaea borealis), the twinflower that would become his favourite.[36]

After Gävle Linnaeus began journeying to Lycksele, a town further away from the coast than he had traveled up till then, examining waterbirds on the way. After five days he reached the town and stayed with the pastor and his wife.[36] In the beginning of June he returned to Umeå after having spent some days in Lycksele, and learning more of the customs of the Sami.[37] (See, e.g., Tablut)

From Umeå he travelled further north into the Scandinavian Mountains passing Old Luleå, where he received a Sami woman's cap on the way.[38] Here he crossed the border to Norway into Sørfold, about 300 kilometres (190 mi) from Old Luleå.[39] Subsequently he traveled to Kalix where he received instructions in assaying. In the middle of September he began his journey back to Uppsala travelling through Finland, taking the boat from Åbo. He returned from his six month long, over 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi), expedition on 10 October having gathered and observed many plants, birds and rocks.[40][41][42] Though Lapland was a region with limited biodiversity, Linnaeus was able to describe about one hundred previously unknown plants. His discoveries would later become the basis of his book Flora Lapponica.[43][44]

In 1734 Linnaeus led a small group of students to Dalarna. The trip, funded by the Governor of Dalarna, aimed to catalogue known natural resources and discover new ones, but also included gathering intelligence on Norwegian mining activities at Røros.[42]

European excursions

Doctorate

Back in Uppsala, Linnaeus' relations with Nils Rosén worsened and thus he gladly accepted an invitation from the student Claes Sohlberg to spend the Christmas holiday in Falun with Sohlberg's family. Sohlberg's father was a mining inspector and let Linnaeus visit the mines near Falun.[45] Sohland's father suggested to Linnaeus that he should bring Sohlberg to Holland and continue to tutor him there for an annual pay. At that time Holland was one of the most revered places to study natural history and a common place for Swedes to take their doctor's degree; Linnaeus, who was interested in both of these, accepted.[46]

In April 1735 Linnaeus and Sohlberg set out for the Netherlands, with Linnaeus to take a doctor's degree in medicine at the University of Harderwijk.[47] On the way they stopped in Hamburg. Here they met the mayor, who proudly showed them a wonder of nature which he possessed: the taxidermied remains of a seven-headed hydra. Linnaeus quickly discovered that it was a fake: jaws and clawed feet from weasels and skins from snakes had been glued together. The provenance of the hydra suggested to Linnaeus that it had been manufactured by monks to represent the Beast of Revelation. As much as this may have upset the mayor, Linnaeus made his observations public and the mayor's dreams of selling the hydra for an enormous sum were ruined. Fearing his wrath, Linnaeus and Sohlberg had to leave Hamburg quickly.[48][49]

When Linnaeus reached Harderwijk, he started taking his degree immediately. First he handed in a thesis on the cause of malaria that he had written in Sweden. He then defended his thesis in a public debate. The next step was to take an oral exam and to diagnose a patient. After less than two weeks he took his degree and became a doctor, at the age of 28.[48][50] During the summer Linnaeus met a friend from Uppsala, Peter Artedi. Prior to their departure from Uppsala, Artedi and Linnaeus had decided that should one of them die, the survivor would finish the other's work. Ten weeks later Artedi drowned in one of the canals of Amsterdam and his unfinished manuscript on the classification of fish was left to Linnaeus to complete.[51][52]

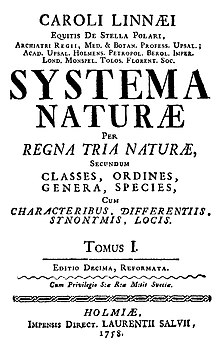

Publishing of Systema Naturae

One of the first scientists Linnaeus met in the Netherlands was Johan Frederik Gronovius to whom Linnaeus showed one of his several manuscripts he had brought with him from Sweden. The manuscript described a new system for classifying plants. When Gronovius saw it, he was very impressed and offered to help pay for the printing. With an additional monetary contribution by the Scottish doctor Isaac Lawson the manuscript was published as Systema Naturae.[53][54]

Linnaeus became acquainted with one of the most respected physicians and botanists in the Netherlands, Herman Boerhaave who tried to convince Linnaeus to make a career there. Boerhaave offered him a journey to South Africa and America but Linnaeus declined, stating he would not stand the heat. Instead Boerhaave suggested that Linnaeus visit the botanist Johannes Burman, which Linnaeus did. After Linnaeus' visit Burman, impressed with his guest's knowledge, decided that Linnaeus should stay with him during the winter. During his stay Linnaeus helped Burman with his Thesaurus Zeylanicus. Burman also helped Linnaeus with the books he was working on: Fundamenta Botanica and Bibliotheca Botanica.[55]

George Clifford

In August, during Linnaeus' stay with Burman, he met George Clifford III, a director of the Dutch East India Company and the owner of a rich botanical garden at the estate of Hartecamp in Heemstede. Clifford was very impressed with Linnaeus' ability to classify plants and invited him to become his physician and superintendent of his garden. Linnaeus had already agreed to stay with Burman over the winter and could thus not accept immediately. However, Clifford offered to compensate Burman by offering him a copy of Sir Hans Sloane's Natural History of Jamaica, a rare book, if he let Linnaeus stay with him and Burman accepted.[56][57] On 24 September 1735 Linnaeus became the botanical curator and house physician at Hartecamp, free to buy any book or plant he wanted.

In July 1736 Linnaeus travelled to England, at Clifford's expense.[58] He went to London to visit Sir Hans Sloane, a collector of Natural History, and see his cabinet,[59] as well as to visit the Chelsea Physic Garden and its keeper Philip Miller. He taught Miller about his new system of subdividing plants, as described in Systema Naturae. Miller was impressed and from then on started to arrange the garden according to Linnaeus' system.[60] Linnaeus also traveled to Oxford University to visit the botanist Johann Jacob Dillenius. He failed however to make Dillenius publicly accept his new classification system. He then returned to Hartecamp, bringing with him many specimens of rare plants.[61] The next year he published Genera Plantarum in which he described 935 genera of plants, shortly thereafter supplemented by Corollarium Generum Plantarum, with another sixty (sexaginta) genera.[62]

His work at Hartecamp led to another book Hortus Cliffortianus, a catalogue of the botanical holdings in the herbarium and botanical garden of Hartecamp, written in nine months, completed in July 1737 but not published until 1738.[55] It contains the first use of the name Nepenthes, which Linnaeus used to describe a genus of pitcher plants.[63][a 4]

Linnaeus stayed with Clifford at Hartecamp until 18 October 1737 (new style) when he left the house in order to return to Sweden. Illness and the kindness of Dutch friends obliged him to stay some months longer in Holland. In May 1738 he set out for Sweden again. On the way home he stayed in Paris for about a month, visiting botanists such as Antoine de Jussieu. After his return, Linnaeus never left Sweden again.[64][65]

Return to Sweden

When Linnaeus returned to Sweden 28 June 1738 he went to Falun where he entered into an engagement to Sara Elisabeth Moræa. Three months later he moved to Stockholm to find employment as a physician and thus making it possible to support a family.[66][67] Once again Linnaeus found a patron; he became acquainted with Count Carl Gustav Tessin who helped Linnaeus get work as a physician at the Admiralty.[68][69] During this time in Stockholm Linnaeus helped found the Royal Swedish Academy of Science. Linnaeus became the first Praeses in the academy by drawing of lots.[70]

Because his economy had improved and was now sufficient to support a family he received permission to marry his fiancée Sara Elisabeth Moræa. Their wedding was held 26 June 1739. Seven months later Sara gave birth to their first son, Carl. Two years later a daughter, Elisabeth Christina was born and the subsequent year Sara gave birth to Sara Magdalena who died at 15 days old. Sara and Linnaeus would later have four other children: Lovisa, Sara Christina, Johannes and Sophia.[66][71]

In May 1741 Linnaeus was appointed Professor of Medicine at Uppsala University, first with the responsibility of the medicine-related matters. Soon he changed place with the other Professor of Medicine, Nils Rosén, and thus was responsible for the Botanical Garden (which he would thoroughly reconstruct and expand), botany and natural history instead. In October that same year his wife and nine-year-old son followed him to live in Uppsala.[72]

Further exploration of Sweden

Öland and Gotland

Ten days after he was appointed Professor he undertook an expedition to the island provinces of Öland and Gotland with six students from the university, to look for plants useful in medicine. First they travelled to Öland and stayed there until 21 June when they sailed to Visby in Gotland. Linnaeus and the students stayed on Gotland for about a month and then returned to Uppsala. During this expedition they found 100 previously unrecorded plants. The observations from the expedition were later published in Öländska och Gothländska Resa, written in Swedish. Like Flora Lapponica it contained both zoological and botanical observations as well as observations concerning the culture in Öland and Gotland.[73][74]

During the summer of 1745, Linnaeus published two more books: Flora Suecica and Fauna Suecica. Flora Suecica was a strictly botanical book while Fauna Suecica was zoological.[66][75] Anders Celsius had created the temperature scale named after him in 1742. Celsius' scale was inverted compared to today, the boiling point at 0 °C and freezing point at 100 °C. In 1745 Linnaeus inverted the scale to its present standard.[76]

Västergötland

In the summer of 1746 Linnaeus was once again commissioned by the Government to carry out an expedition, this time to the Swedish province Västergötland. He set out from Uppsala 12 June and returned 11 August. On the expedition his primarily companion was Erik Gustaf Lidbeck, a student who had accompanied him on his previous journey. Linnaeus described his findings from the expedition in the book Wästgöta-Resa, published the next year.[73][77] After returning from the journey the Government decided Linnaeus should take on another expedition to the southernmost province Scania. This journey was postponed, as Linnaeus felt too busy.[66]

In 1747 Linnaeus was given the title archiater, or chief physician, by the Swedish king Adolf Frederick—a mark of great respect.[78] The same year he was elected member of the Academy of Sciences in Berlin.[79]

Scania

In the spring of 1749 Linnaeus could finally journey to Scania, again commissioned by the Government. With him he brought his student Olof Söderberg. On the way to Scania he made his last visit to his brothers and sisters in Stenbrohult since his father had died the previous year. The expedition was similar to the previous journeys in most aspects but this time he was also ordered to find the best place to grow Walnut and Swedish Whitebeam. These trees were used by the military to make rifles. The journey was successful and Linnaeus' observations were published the next year in Skånska Resa.[80][81]

Rector of Uppsala University

In 1750 Linnaeus became rector of Uppsala University, starting a period where specifically natural sciences were esteemed.[66] The perhaps most important contribution Linnaeus made during his time at Uppsala was to teach; many of his students travelled to various places in the world to collect botanical samples. Linnaeus called the best of these students his "apostles."[82] His lectures were normally very popular and were often held in the Botanical Garden. He tried to teach the students to think for themselves and not trust anybody, not even him. Even more popular than the lectures were the botanical excursions made every Saturday during summer where Linnaeus and his students explored the flora and fauna in the vicinity of Uppsala.[83]

Publishing of Species Plantarum

Linnaeus published Philosophia Botanica in 1751. The book contained a complete survey of the taxonomy system Linnaeus had been using in his earlier works. It also contained information of how to keep a journal on travels and how to maintain a botanical garden.[84]

In 1753 Linnaeus published Species Plantarum, the work which—together with his earlier work Systema Naturae—is internationally accepted as the beginning of modern botanical nomenclature. The book contained 1,200 pages and was published in two volumes. It described over 7,300 species.[85][86] The same year he was dubbed knight of the Order of the Polar Star by the king. Linnaeus was the first civilian in Sweden to become a knight in this order. He was then seldom seen not wearing the order.[87]

Ennoblement

Linnaeus felt Uppsala was too noisy and unhealthy and thus he bought two farms in 1758: Hammarby and Sävja. The next year he bought a neighbouring farm, Edeby. Together with his family he spent the summers at Hammarby; first only a small one-storey house but expanded with a new, bigger main building in 1762.[81][88] In Hammarby Linnaeus made a garden where he could grow plants that could not be grown in the Botanical Garden in Uppsala. He began constructing a museum on a hill behind Hammarby in 1766 where he moved his library and collection of plants. The reason for the move was a fire that destroyed about one third of Uppsala and had threatened his residence there.[89]

Since the initial release of Systema Naturae in 1735 the book had been expanded and reprinted several times; the tenth edition was released in 1758. This edition established itself as the starting point for zoological nomenclature, the equivalent of Species Plantarum.[85][90]

The Swedish king Adolf Frederick granted Linnaeus nobility in 1757, but he was not ennobled until 1761. He took the name von Linné, becoming Carl von Linné. The noble family's coat of arms prominently features a twinflower, one of Linnaeus' favourite plants; it was given the scientific name Linnaea borealis in his honour by Gronovius. The shield in the coat of arms is divided into thirds: red, black and green for the three kingdoms of nature (animal, mineral and vegetable) in Linnaean classification; in the center is an egg "to denote Nature, which is continued and perpetuated in ovo." At the bottom is a phrase in Latin, borrowed from the Aeneid, which reads "FAMAM EXTENDERE FACTIS": We extend our fame by our deeds.[91][92][93]

Last years

Linnaeus was relieved of his duties in the Royal Swedish Academy of Science in 1763 but continued his work there as usual for more than ten years after.[66] In December 1772 Linnaeus stepped down as rector at Uppsala University, mostly due to his declining health.[65][94]

Linnaeus' last years were troubled by illness. He had suffered from a disease called the Uppsala fever in 1764 but survived thanks to the care of Rosén. He got sciatica in 1773 and the next year he had a stroke which partially paralysed him.[95] In 1776 he suffered a second stroke, losing the use of his right side and leaving him bereft of his memory; while still able to admire his own writings, he could not recognize himself as their author.[96][97]

In December 1777 he had another stroke which greatly weakened him, and eventually led to his death 10 January 1778 in Hammarby.[94][98] Despite his desire to be buried in Hammarby, he was interred in Uppsala Cathedral 22 January.[99][100]

His library and collections were left to his widow Sara and their children. Joseph Banks, an English botanist, wanted to buy the collection but Carl refused and moved the collection to Uppsala. However, in 1783 Carl died and Sara inherited the collection, having outlived both her husband and son. She tried to sell it to Banks but he was no longer interested; instead an acquaintance of his agreed to buy the collection. The acquaintance was a 24 year old medical student, James Edward Smith who bought the whole collection: 14,000 plants, 3,198 insects, 1,564 shells, about 3,000 letters and 1,600 books. Smith founded the Linnean Society of London five years later.[100][101]

Apostles

During Linnaeus' time as Professor and Rector of Uppsala University he taught many devoted students, 17 of whom he called "apostles." They were the most promising, most committed students and all of them made botanical expeditions to various places in the world, often with the help of Linnaeus. The amount of this help varied; sometimes he used his influence as Rector to grant his apostles a place on an expedition or a scholarship.[102] To most of the apostles he gave instructions of what to find on their journeys. Abroad the apostles collected and organised new plants, animals and minerals according to Linnaeus' system. Most of them also gave some of their collection to Linnaeus when their journey was finished.[103] Thanks to these students the Linnaean system of taxonomy spread through the world without Linnaeus ever having to travel outside Sweden after his return from Holland.[104] The British botanist William T. Stearn notes that without Linnaeus' new system it would not have been possible for the apostles to collect and organize so many new specimens.[105] Many of the apostles died during their expeditions.

Early expeditions

Christopher Tärnström, the first apostle and a 43-year-old pastor with a wife and children, made his journey in 1746. He boarded a Swedish East India Company ship headed for China. Tärnström never reached his destination, having died of a tropical fever on Côn Sơn Island the same year. Tärnström's widow blamed Linnaeus for making her children fatherless, causing Linnaeus to prefer sending out younger, unmarried students after Tärnström.[106] Six other apostles later died on their expeditions, including the apostles Pehr Forsskål and Pehr Löfling.[105]

Two years after Tärnström's expedition Finnish-born Pehr Kalm set out as the second apostle to North America. There he spent two-and-a-half years studying the flora and fauna of Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey and Canada. Linnaeus was overjoyed when Kalm returned, bringing back with him many pressed flowers and seeds. At least 90 of the 700 North American species described in Species Plantarum had been brought by Kalm.[107]

Cook expeditions and Japan

Daniel Solander was living in Linnaeus' house during his time as a student in Uppsala. Linnaeus was very fond of him, promising Solander his oldest daughter's hand in marriage. On Linnaeus' recommendation Solander travelled to England in 1760 where he met the English botanist Joseph Banks. Together with Banks, Solander joined James Cook on his expedition to Oceania on the Endeavour in 1768-71.[108][109] Solander was not the only apostle to journey with James Cook: Anders Sparrman followed on the Resolution in 1772–75 bound for, among others, Oceania and South America. Sparrman made many other expeditions, one of them to South Africa.[110]

Perhaps the most famous and successful apostle was Carl Peter Thunberg who embarked on a nine-year-long expedition in 1770. He stayed in South Africa for three years and then travelled to Japan. All foreigners in Japan were forced to stay on the island of Dejima outside Nagasaki and it was thus hard for Thunberg to study the flora. However, he managed to persuade some of the translators to bring him different plants and also found plants in the gardens of Dejima. He returned to Sweden in 1779, one year after Linnaeus' death.[111]

Major publications

Systema Naturae

The first edition of Systema Naturae was printed in the Netherlands in 1735. It was a twelve page work.[112] By the time it reached its 10th edition (1758), it classified 4,400 species of animals and 7,700 species of plants. In it, the unwieldy names mostly used at the time, such as "Physalis annua ramosissima, ramis angulosis glabris, foliis dentato-serratis", were supplemented with concise and now familiar "binomials", composed of the generic name, followed by a specific epithet - in the case given, Physalis angulata. These binomials could serve as a label to refer to the species. Higher taxa were constructed and arranged in a simple and orderly manner. Although the system, now known as binomial nomenclature, was developed by the Bauhin brothers (see Gaspard Bauhin and Johann Bauhin) almost 200 years earlier, Linnaeus was the first to use it consistently throughout the work, also in monospecific genera, and may be said to have popularized it within the scientific community.

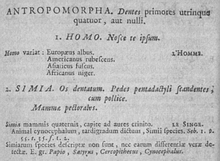

Linnaeus named taxa in ways that struck him as common-sensical; for example, human beings are Homo sapiens (see sapience). He also briefly described a second human species, Homo troglodytes ("cave-dwelling man"). This name was based on a figure and description by Bontius 1658,[113] the figure referred to a female Indonesian or Malayan human and the description to an orang utan.[114] The group "Mammalia" were named for their mammary glands because one of the defining characteristics of mammals is that they nurse their young.

Species Plantarum

Species Plantarum (or, more fully, Species Plantarum, exhibentes plantas rite cognitas, ad genera relatas, cum differentiis specificis, nominibus trivialibus, synonymis selectis, locis natalibus, secundum systema sexuale digestas) was first published in 1753, as a two-volume work. Its prime importance is perhaps that it is the primary starting point of plant nomenclature as it exists today.

In 1754 Linnaeus divided the plant Kingdom into 25 classes. One, Cryptogamia, included all the plants with concealed reproductive parts (algae, fungi, mosses and liverworts and ferns).[115]

Genera Plantarum

Genera plantarum: eorumque characteres naturales secundum numerum, figuram, situm, et proportionem omnium fructificationis partium was first published in 1737, delineating plant genera. It reached its sixth edition by 1764.

Systema Plantarum

Systema Plantarum was a work published posthumously in 1779 that integrated the botanical aspects of Systema Naturae with Species Plantarum (and, defacto, Genera Plantarum) to make a complete work. This work actually presented the fourth edition of Species Plantarum. A follow-up titled Supplementum Plantarum was published by Carolus Linnaeus the Younger in 1782.

Philosophia Botanica

Philosophia Botanica (1751) was a summation of Linnaeus's thinking on plant classification and nomenclature and an elaboration of the work he had previously published in Fundamenta Botanica (1736) and Critica Botanica (1737). Other publications forming part of his plan to reform the foundations of botany include his Classes Plantarum and Bibliotheca Botanica: all were printed in Holland (as well as Genera Plantarum (1737) and Systema Naturae (1735)), the Philosophia being simultaneously released in Stockholm.[116]

Linnaean taxonomy

The establishment of universally accepted conventions for the naming of organisms was Linnaeus' main contribution to taxonomy—his work marks the starting point of binomial nomenclature. In addition Linnaeus developed, during the 18th century expansion of natural history knowledge, what became known as the Linnaean taxonomy; the system of scientific classification now widely used in the biological sciences.

The Linnaean system classified nature within a nested hierarchy, starting with three kingdoms. Kingdoms were divided into Classes and they, in turn, into Orders, which were divided into Genera (singular: genus), which were divided into Species (singular: species). Below the rank of species he sometimes recognized taxa of a lower (unnamed) rank (for plants these are now called "varieties").

Linnaeus' groupings were based upon shared physical characteristics. Only his groupings for animals survive, and the groupings themselves have been significantly changed since their conception, as have the principles behind them. Nevertheless, Linnaeus is credited with establishing the idea of a hierarchical structure of classification which is based upon observable characteristics. While the underlying details concerning what are considered to be scientifically valid "observable characteristics" have changed with expanding knowledge (for example, DNA sequencing, unavailable in Linnaeus' time, has proven to be a tool of considerable utility for classifying living organisms and establishing their evolutionary relationships), the fundamental principle remains sound.

Philosophical views

Views on mankind

According to German biologist Ernst Haeckel the question of man's origin began with Linnaeus. He helped future research in the natural history of man by describing humans just like he described any other plant or animal.[117] Linnaeus was the first person to place humans in a system of biological classification. He put humans under Homo sapiens among the primates in the first edition of Systema Naturae. During his time at Hartecamp he had the opportunity to examine several monkeys and noted several similarities between them and man.[82] He pointed out that both species basically have the same anatomy; except for the speech he found no other differences.[118][a 5] Thus he placed man and monkeys under the same category, Antromorpha, meaning "manlike."[119] This classification received criticism from other botanists such as Johan Gottschalk Wallerius, Jacob Theodor Klein and Johann Georg Gmelin on the ground that it is illogical to describe a human as 'like a man'.[120] In a letter to Gmelin from 1747, Linnaeus replied:[121]

It does not please [you] that I've placed Man among the Antropomorpha, but man learns to know himself. Let's not quibble over words. It will be the same to me whatever name we apply. But I seek from you and from the whole world a generic difference between man and simian that [follows] from the principles of Natural History.[a 6] I absolutely know of none. If only someone might tell me a single one! If I would have called man a simian or vice versa, I would have brought together all the theologians against me. Perhaps I ought to have by virtue of the law of the discipline.

The theological concerns were twofold: first, that putting man at the same level as monkeys or apes would lower the spiritually higher position man was assumed to have in the great chain of being, and second, because the Bible says that man was created in the image of God,[122] if monkeys/apes and humans were not distinctly and separately designed, that would mean monkeys and apes were created in the image of God as well. This was something many could not accept.[123] The conflict between worldviews based on science and theology that was caused by asserting that man was a type of animal would simmer for a century until the much greater, and still ongoing, creation–evolution controversy began in earnest with the publication of On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin in 1859.

After this criticism Linnaeus felt he needed to explain himself more clearly. In the 10th edition of Systema Naturae introduced new terms including Mammalia and Primate, the latter which would replace Antromorpha.[124] The new classification received less criticism but many natural historians still felt that human had been demoted from its former place to rule over nature, not be a part of it. But Linnaeus believed that man biologically belongs to the animal kingdom and thus should be there.[125] In his book Dieta Naturalis he said "One should not vent one's wrath on animals, Theology decree that man has a soul and that the animals are mere aoutomata mechanica, but I believe they would be better advise that animals have a soul and that the difference is of nobility."[126]

Linnaeus also added a second human species in Systema Naturae, the Homo troglodytes or caveman.[127] This name was based on a figure and description by Bontius from 1658, the figure referred to a female Indonesian or Malayan human and the description to an orang utan.[113] In these times tales on human species were based on myths from people who claimed they had seen something looking like a human. Most of these tales were scientifically accepted and in early editions of Systema Naturae many mythical animals were included such as the phoenix, dragon and unicorn. Linnaeus placed them under the category Paradoxa, according to Swedish historian Gunnar Broberg it was to offer a natural explanation and demystify the world of superstition.[128] An example of this, was that Linnaeus did not only settle with trying to classify these mythical creatures, but also tried to find out for example if the Homo troglodytes actually existed, by asking the Swedish East Indian Trade Company to search for one. They did not, however, find any signs of its existence.[129] Broberg believes the new human species Linnaeus described were actually monkeys or native people clad in skins to frighten settlers, whose appearances had been exaggerated in transit to Linnaeus.[130] In 1771 Linné published another name for a non-human primate in the genus Homo, which was Homo lar,[131] this name is currently in use for the lar gibbon as Hylobates lar (Linné, 1771).

Commemoration

Anniversaries of Linnaeus' birth, especially in centennial years, have been marked by major celebrations.[132] In 1807 events were held in Sweden that included Linnaeus' daughters and apostles such as Afzelius who was then head of the short-lived Linnéska institutet. A century later, celebrations of the bicentennial expanded globally and were even larger in Sweden. At Uppsala University, honorary doctorates given to Ernst Haeckel, Francis Darwin and Selma Lagerlöf, among others. The memorials were so numerous that newspaper columnists began to tire of them and printed caricatures of the esteemed Linnaeus.[133] In 1917, on the 210th anniversary of Linnaeus' birth, the Swedish Linnaeus Society was founded and proceeded to restore the Linnaean Garden which had fallen into disrepair. In 2007 tricentennial celebrations were held. During that year a documentary titled Expedition Linnaeus was produced, which was intended to increase public understanding of and respect for nature.

The Linnean Society of London has awarded the Linnean Medal for excellence in botany or zoology since 1888. Starting in 1978, in commemoration of the 200th anniversary of the death of Linnaeus, the Bicentenary Medal of the Linnean Society has been awarded in recognition of work done by a biologist under the age of forty.

The Linnean Society of New South Wales awards a bursary to assist botany, zoology or geology students at the University of Sydney.

The Australian National University campus has a road named Linnaeus Way, which runs past several biology buildings.[134]

Gustavus Adolphus College began its eponymous Linnaeus Arboretum in 1973.

The asteroid 7412 Linnaeus and Linné (crater) on the Earth's moon were named in his honor.

The nightshade species Solanum linnaeanum and twinflower genus Linnaea were named in his honor.

Linnaeus has appeared on numerous Swedish postage stamps and banknotes.[132] In 1986, a new 100 kronor bill was introduced featuring a portrait of Linnaeus, drawings of pollinating plants from his Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum, a sketch of the Linnaean Garden and a quote, often described as Linnaeus' motto, from Philosophia Botanica which reads "OMNIA MIRARI ETIAM TRITISSIMA": Find wonder in all things, even the most commonplace.[135]

Following approval by the Parliament of Sweden, Växjö University and Kalmar College merged on 1 January 2010; the resulting institution was named Linnaeus University in his honor.[136]

-

Celebration in Råshult, 1907.

-

The twinflower, Linnaea borealis was a personal emblem for Linnaeus.

-

The Linné crater on the moon.

-

Bust of Linnaeus adorned with a Swedish student cap, near the Linnaeus arboretum in 2007.

-

The Linnean Medal.

-

Monument to Linnaeus at his birthplace in Råshult.

-

Linnaeus featured on Swedish currency.

-

Statue of Linnaeus in the Royal Academy of London.

-

The logo of Linnéuniversitetet (Linnaeus University).

See also

- History of botany

- History of phycology

- Index cards, which were invented by Linnaeus.

- Linnaeus' flower clock

- List of students of Linnaeus

- Scientific revolution

Footnotes

- ^ a b Carl Linnaeus was born in 1707 on 13 May (Swedish Style) or 23 May according to the modern calendar. According to the Julian calendar he was born 12 May. (Blunt 2004, p. 12)

- ^ Carl Linnaeus's father, Nils, was born with the patronymic Ingemarsson after his father Ingemar Bengtsson and no family surname. However, when Nils was entering the university of Lund he had to take on a family name. Since a lime tree stood on land belonging to Nils' family he chose the name Linnæus after the Swedish name for lime tree, "lind". (Blunt, 2004, 12) The name was spelled with æ ligature. When Carl was born he was therefore named Carl Linnæus, taking his father's family name. (Blunt, 2004, 13) Carl Linnæus spelled his name always with the æ ligature, in handwritten documents and in publications.

- ^ When Carl Linnaeus enrolled in private school as student at the University of Lund, he was registered as 'Carolus Linnæus'. This Latinized form was the name he used when he published his works in Latin. After his ennoblement, in 1761, he took the name Carl von Linné. 'Linné' was thus a shortened and francophone version of 'Linnæus', and the German title 'von' was added to signify his ennoblement. (Blunt, 2004, 171)

- ^ "If this is not Helen's Nepenthes, it certainly will be for all botanists. What botanist would not be filled with admiration if, after a long journey, he should find this wonderful plant. In his astonishment past ills would be forgotten when beholding this admirable work of the Creator!" (translated from Latin by Harry Veitch)

- ^ Frängsmyr et al. (1983). p. 167.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) quotes Linnaeus explaining that the real difference would necessarily be absent from his classification system as it was not a morphological characteristic: "I well know what a splendidly great difference there is [between] a man and a bestia [literally, "beast"; that is, a non-human animal] when I look at them from a point of view of morality. Man is the animal which the Creator has seen fit to honor with such a magnificent mind and has condescended to adopt as his favorite and for which he has prepared a nobler life". - ^ Others who followed were more inclined to give humans a special place in classification; Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in the first edition of his Manual of Natural History (1779), proposed that the primates be divided into the Quadrumana (four-handed, i.e. apes and monkeys) and Bimana (two-handed, i.e. humans). This distinction was taken up by other naturalists, most notably Georges Cuvier. Some elevated the distinction to the level of order. However, the many affinities between humans and other primates — and especially the great apes — made it clear that the distinction made no scientific sense. Charles Darwin wrote, in The Descent of Man in 1871:

The greater number of naturalists who have taken into consideration the whole structure of man, including his mental faculties, have followed Blumenbach and Cuvier, and have placed man in a separate Order, under the title of the Bimana, and therefore on an equality with the orders of the Quadrumana, Carnivora, etc. Recently many of our best naturalists have recurred to the view first propounded by Linnaeus, so remarkable for his sagacity, and have placed man in the same Order with the Quadrumana, under the title of the Primates. The justice of this conclusion will be admitted: for in the first place, we must bear in mind the comparative insignificance for classification of the great development of the brain in man, and that the strongly-marked differences between the skulls of man and the Quadrumana (lately insisted upon by Bischoff, Aeby, and others) apparently follow from their differently developed brains. In the second place, we must remember that nearly all the other and more important differences between man and the Quadrumana are manifestly adaptive in their nature, and relate chiefly to the erect position of man; such as the structure of his hand, foot, and pelvis, the curvature of his spine, and the position of his head.

References

Notes

- ^ a b "What people have said about Linnaeus", Uppsala University website "Linné on line" English language version.

- ^ Linnaeus deceased Uppsala University website "Linné on line" English language version.

- ^ Broberg, Gunnar (2006). p. 7.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ International Plant Names Index Author Details for Linnaeus, Carl (1707-1778)

- ^ p. 4 in Stearn, W. T. 1959. The background of Linnaeus's contributions to the nomenclature and methods of systematic biology. - Systematic Zoology 8 (1): 4-22.

- ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 12.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). p. 8.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Broberg, Gunnar (2006). p. 10.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 13.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Quammen, David (2007-06). "The Name Giver". National Geographic: 1. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 15.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 15–16.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). p. 5.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 16.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). pp. 5–6.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). p. 6.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 16–17.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 17–18.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). pp. 8–11.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 18.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). p. 13.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 21–22.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). p. 15.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). pp. 14–15.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 23–25.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 31–32.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). pp. 19–20.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 32–34.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 34–37.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). pp. 36–37.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Anderson, Margaret J. (1997). p. 40.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Anderson, Margaret J. (1997). pp. 42–43.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). p. 38.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Anderson, Margaret J. (1997). pp. 43–44.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Anderson, Margaret J. (1997). p. 46.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). pp. 42–43.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). pp. 45–47.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Anderson, Margaret J. (1997). pp. 50–51.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). pp. 55–56.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). pp. 63–65.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 39–42.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Broberg, Gunnar (2006). p. 29.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Quammen, David (2007-06). "The Name Giver". National Geographic: 2. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). pp. 38–39.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). p. 74.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). pp. 78–79.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). p. 71.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Anderson, Margaret J. (1997). pp. 60–61.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 90.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). p. 94.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Anderson, Margaret J. (1997). p. 66.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 98–100.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). p. 98.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Anderson, Margaret J. (1997). pp. 62–63.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 100–102.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Anderson, Margaret J. (1997). p. 64.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). pp. 81–82.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). pp. 106–107.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). p. 89.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). pp. 89–90.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). pp. 90–93.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). p. 95.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Veitch, H.J. 1897. Nepenthes. Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society 21(2): 226–262.

- ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). p. 123.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Koerner, Lisbet (1999). p. 56.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Petrusson, Louise. "Carl Linnaeus". Swedish Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). p. 141.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). pp. 146–147.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Koerner, Lisbet (1999). p. 16.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Koerner, Lisbet (1999). pp. 103–105.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). p. 382.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Mary, Gribbin (2008). pp. 49–50.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Koerner, Lisbet (1999). p. 115.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 137–142.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). pp. 117–118.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Koerner, Lisbet (1999). p. 204.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 159.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 165.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). p. 167.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 198–205.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Koerner, Lisbet (1999). p. 116.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Mary, Gribbin (2008). pp. 56–57.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Gribbin56-57" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 173–174.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 221.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Mary, Gribbin (2008). p. 47.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). pp. 198–199.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 166.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 219.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 220–224.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 6.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 199.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 229–230.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Mary, Gribbin (2008). p. 62.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 245.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). p. 232.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1974). pp. 243–245.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Broberg, Gunnar (2006). p. 42.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Mary, Gribbin (2008). p. 63.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Quammen, David (2007-06). "The Name Giver". National Geographic: 4. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Anderson, Margaret J. (1997). pp. 104–106.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). pp. 238–240.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 189–190.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Broberg, Gunnar (2006). pp. 37–39.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Anderson, Margaret J. (1997). pp. 92–93.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 184–185.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 185–186.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Anderson, Margaret J. (1997). pp. 93–94.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Anderson, Margaret J. (1997). p. 96.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 191–192.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 192–193.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). pp. 193–194.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Linnæus, C. 1735. Systema naturæ, sive regna tria naturæ systematice proposita per classes, ordines, genera, & species. - pp. [1-12]. Lugduni Batavorum. (Haak).

- ^ a b p. 84 in Bontius, I. 1658. Historiæ naturalis & medicæ Indiæ Orientalis libri sex. - pp. 1-226, in: Piso, G.: De Indiæ Utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibet. -- pp. [1-22], 1-327 [= 329], [1-5], 1-39, 1-226. Amstelædami. (Elzevier).

- ^ p. 64 in Blumenbach, J. F. 1779. Handbuch der Naturgeschichte. Mit Kupfern. [Erster Theil]. - pp. [1-13], 1-448, Tab. I-II [= 1-2]. Göttingen. (J. C. Dieterich).

- ^ Hoek, C.van den, Mann, D.G. and Jahns, H.M. 2005. Algae An Introduction to Phycology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0 521 30419 9

- ^ Stafleu, Frans A. 1971. Linnaeus and the Linnaeans: the Spreading of their Ideas in Systematic Botany, 1735–1789. Utrecht: International Association for Plant Taxonomy. ISBN 9060460642. p. 157.

- ^ Frängsmyr et al. (1983). pp. 156–157.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Frängsmyr et al. (1983). p. 170.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Frängsmyr et al. (1983). p. 167.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Gmelin's letter to Linnaeus in the Linnean Correspondence

- ^ The Linnean Correspondence. Note: Discussion of translation was originally made in this thread on talk.origins in 2005. Please see Mary, Gribbin (2008). p. 56.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) for an alternate translation: [1] - ^ http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=genesis1:26-27&version=KJV

- ^ Frängsmyr et al. (1983). pp. 171–172.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Frängsmyr et al. (1983). p. 175.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Frängsmyr et al. (1983). pp. 191–192.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Frängsmyr et al. (1983). p. 166.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ p. 24 in Linnæus, C. 1758. Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. - pp. [1-4], 1-824. Holmiæ. (Salvius).

- ^ Frängsmyr et al. (1983). pp. 176–177.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Frängsmyr et al. (1983). p. 186.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Frängsmyr et al. (1983). p. 187.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ p. 521 in Linné, C. a 1771. Mantissa plantarum altera generum editionis VI. et specierum editionis II. - pp. [1-7], 144-588. Holmiæ. (Salvius).

- ^ a b "Making Memorials: Early Celebrations of Linnaeus" by Hanna Östholm, from Special Issue No. 8 of The Linnean (Newsletter and Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London) [2]

- ^ "Linné on line - Caricatures of Linnaeus". Linnaeus.uu.se. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ http://campusmap.anu.edu.au/displaymap.asp?grid=ef54

- ^ "Sveriges Riksbank/Riksbanken - 100-kronor banknote". Riksbank.com. 1 January 2006. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ About Linnaeus University, Linnaeus University website.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Margaret J. (1997). Carl Linnaeus: father of classification. United States: Enslow Publishers. ISBN 109876543.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - Blunt, Wilfrid (2001). Linnaeus: the compleat naturalist. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 0711218412.

- Blunt, Wilfrid (2004). Linnaeus: the compleat naturalist. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 0711223629.

- Broberg, Gunnar (2006). Carl Linnaeus. Stockholm: Swedish Institute. ISBN 9152009122.

- Frängsmyr, Tore; Lindroth, Sten; Eriksson, Gunnar; Broberg, Gunnar (1983). Linnaeus, the man and his work. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0711218412.

- Gribbin, Mary; Gribbin, John; Gribbin, John R (2008). Flower hunters. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199561827.

- Koerner, Lisbet (1999). Linnaeus: Nature and Nation. Harvard: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674097459.

- Stöver, Dietrich Johann Heinrich (1794). Joseph Trapp (ed.). The life of Sir Charles Linnæus. London: Library of Congress. ISBN 0198501226.

Further reading

- Brightwell, C. L. A Life of Linnaeus. London: J. Van Voorst, 1858.

- de Bray, Lys (2001). The Art of Botanical Illustration: A history of classic illustrators and their achievements, pp. 62-71. Quantum Publishing Ltd., London. ISBN 1-86160-425-4.

- Hovey, Edmund Otis. The Bicentenary of the Birth of Carolus Linnaeus. New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1908.

- Sörlin & Fagerstedt, Linné och hans lärjungar, 2004. ISBN 91-27-35590-X

- J.L.P.M. Krol, Linneaus' verblijf op de Hartekamp In: Het landgoed de Hartekamp in Heemstede. Heemstede, 1982. ISBN 90-70712-01-6

External links

Biographies

- Biography at the Department of Systematic Botany, University of Uppsala

- Biography at The Linnean Society of London

- Biography from the University of California Museum of Paleontology

Resources

- The Linnaeus Apostles

- The Linnean Collections

- The Linnean Correspondence

- The Linnaean Dissertations

- Linnean Herbarium

- The Linnæus Tercentenary

Other

- Scientists and Mathematicians on Money: Linneaus is featured on the 100 Swedish Krona banknote.

- Linnaeus was depicted by Jay Hosler in a parody of Peanuts titled: Good ol' Charlie Darwin

- Stained glass depiction of Linnaeus at the All Saints' Chapel in Sewanee: The University of the South.

- Ginkgo biloba tree at the University of Harderwijk, said to have been planted by Linnaeus in 1735.

- The 15 March 2007 issue of the Journal Nature featured a picture of Linnaeus on the cover with the heading "Linnaeus's Legacy" and devoted a substantial portion to items related to Linnaeus and Linnaean taxonomy.

- Woodward Park in Tulsa, Oklahoma has a section called the Linnaeus Teaching Gardens which features a large bronze statue of Linnaeus [3] [4] [5]

Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

- Use dmy dates from September 2010

- Carl Linnaeus

- People from Älmhult Municipality

- 18th-century Latin-language writers

- Phycologists

- Arachnologists

- Botanists active in Europe

- Bryologists

- Burials at Uppsala Cathedral

- Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Historical definitions of race

- Swedish botanists

- Swedish biologists

- Swedish entomologists

- Swedish Lutherans

- Swedish mammalogists

- Swedish mycologists

- Swedish ornithologists

- Swedish nobility

- 18th-century Swedish physicians

- Swedish taxonomists

- Pteridologists

- University of Harderwijk alumni

- Uppsala University alumni

- Uppsala University faculty

- Botanical nomenclature

- 1707 births

- 1778 deaths