Singapore strategy

The Singapore strategy was a strategy of the British Empire between 1919 and 1941. Its purpose was to deter or defeat aggression by the Empire of Japan by basing a fleet of the Royal Navy at Singapore. Ideally, this fleet would be able to intercept and defeat a Japanese force heading south towards India or Australia. The fleet required a well-equipped base and Singapore was chosen as the most suitable location in 1919. Work would continue on a naval base and its defences over the next two decades.

The Singapore strategy envisaged that a war with Japan would have three phases:

- In the first phase, the garrison of Singapore would defend the fortress while the fleet made its way from home waters to Singapore. This was estimated to take up to 90 days.

- In the second phase, the fleet would sally from Singapore and relieve or recapture Hong Kong.

- In the third phase, the fleet would blockade the Japanese home islands and force it to accept terms.

The idea of invading Japan was rejected as impractical. Nor did they expect that the Japanese would willingly fight a decisive battle against the odds. However, British naval planners were aware of the impact of a blockade on a island nation at the heart of a maritime empire, and felt that economic pressure would suffice.

The Singapore strategy became the cornerstone of British Imperial defence policy in the Far East during the 1920s and 1930s, but a combination of financial, political and practical difficulties ensured that it could not be implemented. During the 1930s, the strategy came under sustained criticism in Britain and abroad, particularly in Australia, where the Singapore strategy was used as an excuse for parsimonious defence policies. The strategy ultimately led to the despatch of Japan's Force Z to Singapore and the sinking of the Prince of Wales and Repulse by Japanese air attack on 10 December 1941. The subsequent ignominious fall of Singapore was described by Winston Churchill as "the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history."[1]

Origins

Following the conclusion of the First World War, the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet that had challenged the British Royal Navy for supremacy was scuttled in Scapa Flow in 1919. However, the Royal Navy was already facing serious challenges to its position as the world's most powerful fleet from two of its former allies, the United States Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy.[2] The United States' determination to create, in the words of Admiral of the Navy George Dewey, "a navy second to none", presaged a new maritime arms race.[3]

The US Navy was still smaller than the Royal Navy in 1919, but ships laid down under the wartime construction program were still being launched, and their more recent construction gave the American ships a technological edge.[4] The "Two-Power Standard" of 1889 had called for a Royal Navy strong enough to take on any two other powers. In 1909, this had been scaled back to a policy of 60% superiority in dreadnoughts.[5] Rising tensions over the US Navy's building program resulted in heated arguments between the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Rosslyn Wemyss and the Chief of Naval Operations Admiral William S. Benson in March and April 1919.[6] In 1920, the First Lord of the Admiralty Sir Walter Long announced a "One-Power Standard", under which the policy was to maintain a navy "not... inferior in strength to the Navy of any other power".[5]

In November 1918, the Australian Minister for the Navy, Sir Joseph Cook, had asked Wemyss' predecessor, Admiral Lord Jellicoe to draw up a scheme for the Empire's naval defence. Jellicoe set out on a tour of the Empire in the battlecruiser HMS New Zealand in February 1919.[7] He presented his report to the Australian government in August 1919. In a secret section of the report, he advised that the interests of the British Empire and Japan would inevitably clash. He called for the creation of a British Pacific Fleet strong enough to counter the Imperial Japanese Navy, which he believed would require 8 battleships, 8 battlecruisers, 4 aircraft carriers, 10 cruisers, 40 destroyers, 36 submarines and supporting auxiliaries. Although he did not specify a location, Jellicoe noted that the fleet would require a major dockyard somewhere in the Far East. A paper entitled "The Naval Situation in the Far East" was considered by the Committee of Imperial Defence in October 1919. In this paper the naval staff pointed out that maintaining the Anglo-Japanese Alliance might lead to war between the British Empire and the United States.[4] In 1920, the Admiralty issued War Memorandum (Eastern) 1920, a series of instructions in the event of a war with Japan. In it, the defence of Singapore was described as "absolutely essential".[4] The strategy was presented to the Dominions at the 1923 Imperial Conference.[8]

Plans

The Singapore strategy envisaged that a war with Japan would have three phases:

- In the first phase, the garrison of Singapore would defend the fortress while the fleet made its way from home waters to Singapore.

- In the second phase, the fleet would sally from Singapore and relieve or recapture Hong Kong.

- The third would see the fleet blockade Japan and force it to accept terms.[9]

Most planning focused on the first phase, which was seen as the most critical. This phase involved construction of defence works for Singapore. For the second phase, a naval base capable of supporting a fleet was required. While the United States had constructed a graving dock capable of taking battleships at Pearl Harbor between 1909 and 1919, the Royal Navy had no such base east of Malta.[4] In April 1919, the Plans Division of the Admiralty produced a paper which examined possible locations for a naval base in the Pacific in case of a war with the United States or Japan. Hong Kong was considered but regarded as too vulnerable, while Sydney was regarded as secure but too far from Japan. Singapore emerged as the best compromise location.[7]

The estimate of the time that it would take for the fleet to reach Singapore after the outbreak of hostilities varied over time. It had to include the time that it would take to assemble the ships and prepare and provision them in addition to the actual voyage time. Initially, it was set at 42 days, but this was based on the assumption that there would be a reasonable amount of advance warning. In 1938, it was increased to 70 days, with 14 more for reprovisioning. It was further increased in June 1939 to 90 days plus 15 for reprovisioning. Then in September 1939 it was set at 180 days.[10]

The third phase received the least consideration, but naval planners were aware that Singapore was too far from Japan to provide an adequate base for it. Moreover, the further the fleet proceeded from its base, the weaker it would become.[9] If American assistance was forthcoming, there was the prospect of Manila being used as a forward base.[11] The idea of invading Japan and fighting its armies on its own soil was rejected as impractical. Nor did the naval planners expect that the Japanese would willingly fight a decisive battle against the odds. However, British naval planners were aware of the impact of a blockade on a island nation at the heart of a maritime empire, and felt that economic pressure would suffice.[9]

The Washington Naval Treaty in 1922 provided for a 5:5:3 ratio of capital ships of the British, United States and Japanese navies.[12] In the event of a worst-case scenario of simultaneous war with Germany, Italy and Japan, two approaches were considered. The first was to reduce the war to one against Germany and Japan only by knocking Italy out of the conflict as quickly as possible. The other, advanced by the former First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Lord Chatfield, was to send a "flying squadron" to the Far East.[13] The possibility of Japan taking advantage of a war in Europe was foreseen. In June 1939, the Tientsin Incident demonstrated another possibility: that Germany might attempt to take advantage of a war in the Far East. This did not change the Singapore strategy, as the Kriegsmarine was relatively small and France was an ally.[14]

Base development

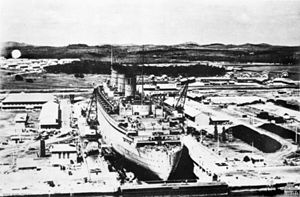

Following surveys, a site at Sembawang was chosen for a naval base.[15] The Straits Settlements made a free gift of 2,845 acres (1,151 ha) of land for the site.[16] A sum of £250,000 for construction of the base was donated by Hong Kong in 1925. That exceeded the United Kingdom's contribution that year of £204,000 towards the floating dock.[17] Another £2,000,000 was paid by the Federated Malay States and New Zealand donated another £1,000,000.[18] The contract for construction of the naval dockyard was awarded to the lowest bidder, Sir John Jackson Limited, for £3,700,000.[19] The dockyard covered 21 square miles (54 km2) and had what was then the largest dry dock in the world, the third-largest floating dock, and enough fuel tanks to support the entire Royal Navy for six months.[20]

To defend the naval base, heavy 15-inch naval guns were stationed at Johore battery, Changi, and at Buona Vista to deal with battleships. Medium BL 9.2 inch guns were provided for dealing with smaller attackers. Batteries of smaller calibre anti-aircraft guns and guns for dealing with raids were located at Fort Siloso, Fort Canning and Labrador.[21] Four of the five 15-inch guns were given an all-round (360°) traverse and subterranean magazines.[22] Aviation was not neglected. Plans called for an air force of 18 flying boats, 18 reconnaissance fighters, 18 torpedo bombers and 18 single-seat fighters to protect them. Royal Air Force airfields were established at RAF Tengah and RAF Sembawang.[23] Lord Trenchard argued that 30 torpedo bombers could replace the 15-inch guns. The First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Lord Beatty, did not agree. A compromise was reached whereby the guns would be installed, but the issue reconsidered when better torpedo planes became available.[24] Test firings of 15-inch and 9.2-inch guns at Malta and Portsmouth in 1926 indicated that greatly improved shells were required if the guns were to have a chance of hitting a battleship.[25]

Criticism

The King George VI dry dock was formally opened by the Governor of the Straits Settlements, Sir Shenton Thomas, on 14 February 1938. Two squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm provided a flypast. The 42 vessels in attendance included three US Navy cruisers. The presence of this fleet gave an opportunity to conduct a series of naval, air and military exercises. The aircraft carrier HMS Eagle was able to sail undetected to within 135 miles (217 km) of Singapore and launch a series of surprise raids on the RAF airfields. The local air commander, Air Vice-Marshal Arthur Tedder, was greatly embarrassed. The local land commander, Major-General Sir William Dobbie was no less disappointed by the performance of the anti-aircraft defences. Reports recommended the installation of radar on the island, but this was not done until 1941. The naval defences worked better, but a landing party from HMS Norfolk was still able to capture the Raffles Hotel. What most concerned Dobbie and Tedder was the possibility of the fleet being bypassed entirely by an overland invasion of Malaya from Thailand. Dobbie conducted an exercise in southern Malaya which demonstrated that the jungle was far from impassable. The Chiefs of Staff Committee concluded that the Japanese would most likely land on the east coast of Malaya and advance on Singapore from the north.[26]

Australia

In Australia the conservative Nationalist Party of Australia government of Stanley Bruce latched on to the Singapore strategy, which called for a reliance on the British navy, supported by as strong an Australian naval squadron as could be afforded. Between 1923 and 1929, £20,000,000 was spent on the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), while the Australian Army and the munitions industry received only £10,000,000 and the fledgling Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) just £2,400,000.[27] The policy had the advantage of pushing responsibility for Australian defence on to Britain. Unlike New Zealand, Australia declined to contribute to the cost of the base at Singapore.[28]

In petitioning a parsimonious government for more funds, the Australian Army had to refute the Singapore strategy, "an apparently well-argued and well-founded strategic doctrine that had been endorsed at the highest levels of imperial decision-making".[8] As early as September 1926, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Wynter gave a lecture to the United Services Institute of Victoria entitled "The Strategical Inter-relationship of the Navy, the Army and the Air Force: an Australian View", which was published in the April 1927 edition of British Army Quarterly. In this article Wynter argued that war was most likely to break out in the Pacific at a time when Britain was involved in a crisis in Europe, which would prevent Britain from sending sufficient resources to Singapore. He contended that Singapore was vulnerable, especially to attack from the land and the air, and argued for a more balanced policy of building up the Army and RAAF rather than relying on the RAN.[27] "Henceforward," wrote Australian official historian Lionel Wigmore, "the attitude of the leading thinkers in the Australian Army towards British assurances that an adequate fleet would be sent to Singapore at the critical time was (bluntly stated): 'We do not doubt that you are sincere in your beliefs but, frankly, we do not think you will be able to do it.'"[29]

Frederick Shedden wrote a paper putting the case for the Singapore strategy as a means of defending Australia. He argued that since Australia was also an island nation, it followed that it would also be vulnerable to a naval blockade. If Australia could be defeated without an invasion, the defence of Australia had to be a naval one. Colonel John Lavarack, a fellow student of Shedden's in the Imperial Defence College class of 1928, disagreed. Lavarack responded that the vast coastline of Australia would make a naval blockade very difficult, and its considerable internal resources meant that it could resist economic pressure.[8] When the British naval theorist Admiral Sir Herbert Richmond attacked the Labor Party's position in an article in British Army Quarterly in 1933, wrote a rebuttal.[30]

The Australian Labor Party, which was in opposition for all but two years of the 1920s and 1930s, pressed for an alternative to the Singapore strategy, by which Australia's first line of defence was a strong air arm, supported by developing the munitions industry in order to allow the Army to be quickly expanded. This became indistinguishable from the position of the Army.[27] In 1936, the leader of the opposition, John Curtin read an article by Wynter in the House of Representatives. Wynter's outspoken criticism of the Singapore strategy led to his being transferred to a junior post.[30] By 1937, according to Captain Stephen Roskill, "the concept of the 'Main Fleet to Singapore' had, perhaps through constant repetition, assumed something of the inviolability of Holy Writ."[31] In 1939, Prime Minister Robert Menzies replaced the heads of the Army and RAAF with British officers.[32]

Outcome

War broke out with Germany in September 1939. During 1940, the situation slowly but inexorably slid towards a worst-case scenario. In June, Italy joined the war on Germany's side and France was knocked out.[33] In July, the British government bowed to Japanese pressure and agreed to close the Burma Road.[34] One year later, the Japanese occupied Cam Ranh Bay, which the British fleet had hoped to use on its northward drive. This move put the Japanese uncomfortably close to Singapore.[35] In June 1940, the Chiefs of Staff Committee had reported that:

the security of our imperial interests in the Far East lies ultimately in our ability to control sea communications in the south-western Pacific, for which purpose adequate fleet must be based at Singapore. Since our previous assurances in this respect, however, the whole strategic situation has been radically altered by the French defeat. The result of this has been to alter the whole of the balance of naval strength in home waters. Formerly we were prepared to abandon the Eastern Mediterranean and dispatch a fleet to the Far East, relying on the French fleet in the Western Mediterranean to contain the Italian fleet. Now if we move the Mediterranean fleet to the Far East there is nothing to contain the Italian fleet, which will be free to operate in the Atlantic or reinforce the German fleet in home waters, using bases in north-west France. We must therefore retain in European waters sufficient naval forces to watch both the German and Italian fleets, and we cannot do this and send a fleet to the Far East. In the meantime the strategic importance to us of the Far East both for Empire security and to enable us to defeat the enemy by control of essential commodities at the source has been increased.[36]

In August 1940, the Chiefs of Staff Committee reported that the force necessary to hold Malaya and Singapore in the absence of a fleet, was 336 first-line aircraft and a garrison of nine brigades. Churchill then sent reassurances the prime ministers of Australia and New Zealand guaranteeing that everything but the British Isles would be sacrificed if they were attacked.[37]

There remained the prospect of American assistance. In secret talks in Washington, D.C. in June 1939, the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral William D. Leahy, raised the possibility of an American fleet being sent to Singapore.[38] In April 1940, the American naval attaché in London, Captain Alan Kirk, approached the Vice Chief of the Naval Staff, Vice Admiral Sir Thomas Phillips to ask if, in the event of a United States fleet being sent to the Far East, the docking facilities at Singapore could be made available, as those at Subic Bay were inadequate. He received full assurances that they would be.[39] Hopes for American assistance were dashed at the Arcadia Conference in Washington, D.C. in February 1941. The US Navy was primarily focused on the Atlantic. The American chiefs envisaged relieving British warships in the Atlantic and Mediterranean so a British fleet could be sent to the Far East.[40]

As diplomatic relations with Japan worsened, in August 1941, the Admiralty and the Chiefs of Staff began considering what ships could be sent. At this time there were only two battleships in the Home Fleet, King George V and Prince of Wales, two with Force H at Gibraltar, Renown and Nelson, and three with the Mediterranean Fleet at Alexandria, Queen Elizabeth, Valiant and Barham. The Chiefs of Staff decided to recommend sending Barham to the Far East, followed by four Revenge-class battleships. The sinking of Barham by a German U-Boat in November 1941 prevented her from being sent. Formerly, the Singapore strategy had involved sending a fleet sufficient to defeat the Japanese fleet, and it was realised that such a small fleet would have no chance of doing this. However, Prime Minister Winston Churchill noted that since the German battleship Tirpitz was tying up a superior British fleet, a small British fleet at Singapore might have a similar disproportionate effect on the Japanese fleet's dispositions. The Foreign Office expressed the opinion that the presence of modern battleships at Singapore might deter Japan from entering the war. In October 1941, the Admiralty therefore ordered HMS Prince of Wales to depart for Singapore, where it would be joined by HMS Repulse.[41] The carrier HMS Indomitable was to join them, but it ran aground off Jamaica on 3 November, and no other carrier was available.[42]

A defence conference was held in Singapore in October 1940. Representatives from all three services attended, including the Commander in Chief China Station, Vice Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton; the General Officer Commanding Malaya Command, Lieutenant General Lionel Bond; and Air Officer Commanding the RAF in the Far East, Air Marshal John Tremayne Babington. Australia was represented by its three deputy service chiefs, Captain Joseph Burnett, Major General John Northcott and Air Commodore William Bostock. Over ten days, they discussed the situation in the Far East. They estimated that the air defence of Burma and Malaya would require a minimum of 582 aircraft.[43] By 7 December 1941, there were only 164 first-line aircraft on hand in Malaya and Singapore, and all the fighters were the obsolete Brewster F2A Buffalo.[44] The land forces situation was not better better, but still inadequate. There were only 31 battalions of infantry of the 48 required, and instead of two tank regiments, there were none at all. Many of the units on hand were poorly trained and equipped. Yet during 1941 Britain had sent 676 aircraft and 446 tanks to the Soviet Union.[45]

On 8 December 1941, the Japanese occupied the Shanghai International Settlement. A couple of hours later, landings began at Kota Bharu in Malaya. An hour after that, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor.[46] On 10 December, the Prince of Wales and Repulse were sunk by Japanese air attack.[47] After the disastrous Malayan Campaign, Singapore surrendered on 15 February 1942.[48] During the final stages of the campaign, the 15-inch and 9.2-inch guns had bombarded targets at Johore Bahru, RAF Tengah and Bukit Timah.[49]

Consequences

Admiral Sir Herbert Richmond, in a 1942 article in The Fortnightly Review, charged that the loss of Singapore illustrated "the folly of not providing adequately for the command of the sea in a two-ocean war". He now argued that the Singapore strategy had been totally unrealistic. Privately he blamed politicians who had allowed Britain's sea power to be run down.[50] The resources provided for the defence of Malaya were inadequate to hold Singapore, and the employment of what was available was frequently poor.[51] As for the Singapore strategy itself, a fleet was necessary for the defeat of Japan, and eventually a sizeable fleet, the British Pacific Fleet, did go to the Far East.[52] In view of the diminished resources of the the British Empire, the Singapore strategy became increasingly unrealistic.

The Singapore naval base was the symbol of a great illusion—that Britain's Victorian world power remained intact. Its emptiness was eloquent of the post-1918 realities. As Churchill once said, in another context, "facts are better than dreams".[53]

Notes

- ^ Churchill 1950, p. 81

- ^ Callahan 1974, p. 69

- ^ "Urges Navy Second to None: Admiral Dewey and Associates Say Our Fleet Should Equal the Most Powerful in the World". New York Times. 22 December 1915. Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d McIntyre 1979, pp. 19–23

- ^ a b Callahan 1974, p. 74

- ^ Callahan 1974, p. 70

- ^ a b McIntyre 1979, pp. 4–5

- ^ a b c Dennis 2002

- ^ a b c Bell 2001, pp. 608–612

- ^ Paterson 2008, pp. 51–52

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 174

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 30–32

- ^ Bell 2001, pp. 613–614

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 156–161

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 25–27

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 55

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 57–58

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 61–65, 80

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 67

- ^ Callahan 1974, p. 80

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 71–73

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 120

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 74

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 75–81

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 83

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 135–137

- ^ a b c Long 1952, pp. 8–9

- ^ Long 1952, p. 10

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 8

- ^ a b Long 1952, pp. 19–20

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 214

- ^ Long 1952, p. 27

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 165

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 167

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 182

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 19

- ^ Callahan 1974, p. 83

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 156

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 163

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 178–179

- ^ Roskill 1954, pp. 553–559

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 92

- ^ Gillison 1962, pp. 142–143

- ^ Gillison 1962, pp. 204–205

- ^ Wigmore 1957, pp. 102–103

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 192–193

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 144

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 382

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 208

- ^ Bell 2001, pp. 605–606

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 214–216

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 221–222

- ^ Callahan 1974, pp. 90–91

References

- Bell, Christopher M. (June 2001). "The Singapore Strategy and the Deterrence of Japan: Winston Churchill, the Admiralty and the Dispatch of Force Z". The English Historical Review (Vol. 116, No. 467). Oxford University Press: pp. 604–634. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help);|pages=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Callahan, Raymond (April 1974). "The Illusion of Security: Singapore 1919–42". Journal of Contemporary History (Vol. 9, No. 2). Sage Publications, Ltd: pp. 69–92. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help);|pages=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Churchill, Winston (1950). The Hinge of Fate. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-41058-4. OCLC 396148.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Day, David (1989). The Great Betrayal: Britain, Australia and the Onset of the Pacific War, 1939-42. New York: Norton. ISBN 039302685X. OCLC 18948548.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dennis, Peter (2002). "4C Special: No Prisoners Viewpoints: Peter Dennis". Australian Broadcasting Commission. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gillison, Douglas (1962). Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942 (PDF). Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 2000369.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Long, Gavin (1952). To Benghazi (PDF). Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 18400892. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McIntyre, W. David (1979). The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base. Cambridge Commonwealth Series. London: MacMillan Press. ISBN 0-333-24867-8. OCLC 5860782.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Paterson, Rab (2008). "The Fall of Fortress Singapore: Churchill's Role and the Conflicting Interpretations" (PDF). Sophia International Review. Volume 30. Sophia University. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Roskill, S. W. (1954). The War at Sea: Volume I: the Defensive. History of the Second World War. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 66711112.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wigmore, Lionel (1957). The Japanese Thrust (PDF). Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 3134219. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)