Bantu peoples

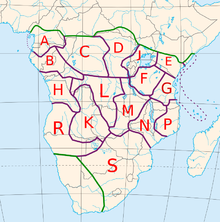

Approximate distribution of Bantu peoples divided into zones according to the Guthrie classification of Bantu languages | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | |

| Languages | |

| Bantu languages: There are over 140 different Bantu languages. | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Islam, Animism |

Bantu is used as a general label for 300-600 ethnic groups in Africa of speakers of Bantu languages, distributed from Cameroon east across Central Africa and Eastern Africa to Southern Africa. Estimated at approximately 335 million (2007), these ethnic groups form about a third of Africa's total population. [citation needed]

The Bantu family is fragmented into hundreds of individual groups, none of them larger than a few million people (the largest being the Zulu with some 10 million). The Bantu language Swahili with its merely 5-10 million native speakers is of super-regional importance as tens of millions fluently command it as a second language.

Etymology

Bantu or its various forms means the people or humans. The word appears in all Bantu languages in various forms, for example as watu in Swahili, batu in Lingala, abantu in Zulu and Luganda, Vanhu in Shona and Vandu in some Luhya dialects.

Origins and expansion

2 = ca.1500 BC first migrations

2.a = Eastern Bantu, 2.b = Western Bantu

3 = 1000–500 BC Urewe nucleus of Eastern Bantu

4–7 = southward advance

9 = 500 BC–0 Congo nucleus

10 = 0–1000 AD last phase[1][2][3]

Current scholarly understanding places the ancestral proto-Bantu homeland near the southwestern modern boundary of Nigeria and Cameroon ca. 4,000 years ago (2000 B.C.), and regards the Bantu languages as a branch of the Niger–Congo language family.[4] This view represents a resolution of debates in the 1960s over competing theories advanced by Joseph Greenberg and Malcolm Guthrie, in favor of refinements of Greenberg's theory. Based on wide comparisons including non-Bantu languages, Greenberg argued that Proto-Bantu, the hypothetical ancestor of the Bantu languages, had strong ancestral affinities with a group of languages spoken in Southeastern Nigeria. He proposed that Bantu languages had spread east and south from there, to secondary centers of further dispersion, over hundreds of years.

Using a different comparative method focused more exclusively on relationships among Bantu languages, Guthrie argued for a single central African dispersal point spreading at a roughly equal rate in all directions. Subsequent research on loanwords for adaptations in agriculture and animal husbandry and on the wider Niger–Congo language family rendered that thesis untenable. In the 1990s Jan Vansina proposed a modification of Greenberg's ideas, in which dispersions from secondary and tertiary centers resembled Guthrie's central node idea, but from a number of regional centers rather than just one, creating linguistic clusters.[5]

It is unclear when exactly the spread of Bantu-speakers began from their core area as hypothesized ca. 5,000 years ago. By 3,500 years ago (1500 B.C.) in the west, Bantu-speaking communities had reached the great Central African rain forest, and by 2,500 years ago (500 B.C.) pioneering groups had emerged into the savannahs to the south, in what are now the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola and Zambia. Another stream of migration, moving east, by 3,000 years ago (1000 B.C.) was creating a major new population center near the Great Lakes of East Africa, where a rich environment supported a dense population. Movements by small groups to the southeast from the Great Lakes region were more rapid, with initial settlements widely dispersed near the coast and near rivers, due to comparatively harsh farming conditions in areas farther from water. Pioneering groups had reached modern KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa by A.D. 300 along the coast, and the modern Northern Province (encompassed within the former province of the Transvaal) by A.D. 500.[6]

Before the expansion of farming and herding peoples, including those speaking Bantu languages, Africa south of the equator was populated by neolithic hunting and foraging peoples. Some of them were ancestral to modern Central African forest peoples (so-called Pygmies) who now speak Bantu languages. Others were proto-Khoisan-speaking peoples, whose few modern hunter-forager and linguistic descendants today occupy the arid regions around the Kalahari desert. Many more Khoekhoe and San descendants have a Coloured identity in South Africa and Namibia, speaking Afrikaans and English. The small Hadza and Sandawe-speaking populations in Tanzania, whose languages are proposed by many to have a distant relationship to Khoekhoe and San languages (although the hypothesis that the Khoisan languages are a single family is disputed by many, and the name is simply used for convenience), comprise the other modern hunter-forager remnant in Africa.

Over a period of many centuries, most hunting-foraging peoples were displaced and absorbed by incoming Bantu-speaking communities, as well as by Ubangian, Nilotic and Central Sudanic language-speakers in North Central and Eastern Africa. The Bantu expansion was a long series of physical migrations, a diffusion of language and knowledge out into and in from neighboring populations, and a creation of new societal groups involving inter-marriage among communities and small groups moving to communities and small groups moving to new areas.

After their movements from their original homeland in West Africa, Bantus also encountered in East Africa peoples of Cushitic origin. As cattle terminology in use amongst the few modern Bantu pastoralist groups suggests, the Bantu migrants would acquire cattle from their new Cushitic neighbors. Linguistic evidence also indicates that Bantus likely borrowed the custom of milking cattle directly from Cushitic peoples in the area.[7] Later interactions between Bantu and Cushitic peoples resulted in Bantu groups with significant Cushitic admixture and culturo-linguistic influences, such as the Herero herdsmen of southern Africa.[8][9]

On the coastal section of East Africa, another mixed Bantu community developed through contact with Muslim Arab and Persian traders. The Swahili culture that emerged from these exchanges evinces many Arab and Islamic influences not seen in traditional Bantu culture, as do the many Afro-Arab members of the Bantu Swahili people. With its original speech community centered on the coastal parts of Zanzibar, Kenya and Tanzania -- a seaboard referred to as the Swahili Coast -- the Bantu Swahili language contains many Arabic loan-words as a consequence of these interactions.[10]

Between the 14th and 15th centuries, Bantu-speaking states began to emerge in the Great Lakes region in the savannah south of the Central African rainforest. On the Zambezi river, the Monomatapa kings built the famous Great Zimbabwe complex, a civilization whose origins and ethnic affiliations are uncertain. From the 16th century onward. processes of state formation amongst Bantu peoples increased in frequency. This was probably due to denser population (which led to more specialized divisions of labor, including military power, while making emigration more difficult); to increased interaction amongst Bantu-speaking communities with Chinese, European, Indonesian and Arab traders on the coasts; to technological developments in economic activity; and to new techniques in the political-spiritual ritualization of royalty as the source of national strength and health.[11]

The use of the term "Bantu" in South Africa

In the 1920s relatively liberal white South Africans, missionaries and the small black intelligentsia began to use the term "Bantu" in preference to "Native" and more derogatory terms (such as "Kaffir") to refer collectively to Bantu-speaking South Africans. After World War II, the racialist National Party governments adopted that usage officially, while the growing African nationalist movement and its liberal white allies turned to the term "African" instead, so that "Bantu" became identified with the policies of apartheid. By the 1970s this so discredited "Bantu" as an ethno-racial designation that the apartheid government switched to the term "Black" in its official racial categorizations, restricting it to Bantu-speaking Africans, at about the same time that the Black Consciousness Movement led by Steve Biko and others were defining "Black" to mean all racially oppressed South Africans (Africans, Coloureds and Indians).

Examples of South African usages of "Bantu" include:

- One of South Africa's politicians of recent times, General Bantubonke Harrington Holomisa (Bantubonke is a compound noun meaning "all the people"), is known as Bantu Holomisa.

- The South African apartheid governments originally gave the name "bantustans" to the eleven rural reserve areas intended for a spurious, ersatz independence to deny Africans South African citizenship. "Bantustan" originally reflected an analogy to the various ethnic "-stans" of Western and Central Asia. Again association with apartheid discredited the term, and the South African government shifted to the politically appealing but historically deceptive term "ethnic homelands". Meanwhile the anti-apartheid movement persisted in calling the areas bantustans, to drive home their political illegitimacy.

- The abstract noun ubuntu, humanity or humaneness, is derived regularly from the Nguni noun stem -ntu in isiXhosa, isiZulu and siNdebele. In siSwati the stem is -ntfu and the noun is buntfu.

- In the Sotho–Tswana languages of southern Africa, batho is the cognate term to Nguni abantu, illustrating that such cognates need not actually look like the -ntu root exactly. The early African National Congress of South Africa had a newspaper called Abantu-Batho from 1912–1933, which carried columns in English, isiZulu, Sesotho, and isiXhosa.

See also

Notes

- ^ The Chronological Evidence for the Introduction of Domestic Stock in Southern Africa

- ^ A Brief History of Botswana

- ^ On Bantu and Khoisan in (Southeastern) Zambia, (in German)

- ^ Erhet & Posnansky, eds. (1982), Newman (1995)

- ^ Vansina (1995)

- ^ Newman (1995), Ehret (1998), Shillington (2005)

- ^ J. D. Fage, A history of Africa, Routledge, 2002, p.29

- ^ Was there an interchange between Cushitic pastoralists and Khoisan speakers in the prehistory of Southern Africa and how can this be detected?

- ^ Robert Gayre, Ethnological elements of Africa, (The Armorial, 1966), p.45

- ^ Daniel Don Nanjira, African Foreign Policy and Diplomacy: From Antiquity to the 21st Century, ABC-CLIO, 2010, p.114

- ^ Shillington (2005)

References

- Christopher Ehret, An African Classical Age: Eastern and Southern Africa in World History, 1000 B.C. to A.D. 400, James Currey, London, 1998

- Christopher Ehret and Merrick Posnansky, eds., The Archaeological and Linguistic Reconstruction of African History, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1982

- April A. Gordon and Donald L. Gordon, Understanding Contemporary Africa, Lynne Riener, London, 1996

- John M. Janzen, Ngoma: Discourses of Healing in Central and Southern Africa, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1992

- James L. Newman, The Peopling of Africa: A Geographic Interpretation, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1995. ISBN 0-300-07280-5.

- Kevin Shillington, History of Africa, 3rd ed. St. Martin's Press, New York, 2005

- Jan Vansina, Paths in the Rainforest: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1990

- Jan Vansina, "New linguistic evidence on the expansion of Bantu", Journal of African History 36:173–195, 1995