Origami

Origami (折り紙, from ori meaning "folding", and kami meaning "paper"; kami changes to gami due to rendaku) art of paper folding, which started in the 17th century AD at the latest and was popularized outside of Japan in the mid-1900s. It has since then evolved into a modern art form. The goal of this art is to transform a flat sheet of material into a finished sculpture through folding and sculpting techniques, and as such the use of cuts or glue are not considered to be origami. Paper cutting and gluing is usually considered kirigami.

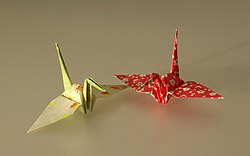

origami folds is small, but they can be combined in a variety of ways to make intricate designs. The best known origami model is probably the Japanese paper crane. In general, these designs begin with a square sheet of paper whose sides may be different colors or prints. Traditional Japanese origami, which has been practiced since the Edo era (1603–1867), has often been less strict about these conventions, sometimes cutting the paper or using nonsquare shapes to start with.

The principles of origami are also being used in stents, packaging and other engineering structures.[1]

History

There is much speculation about the origin of Origami. While Japan seems to have had the most extensive tradition, there is evidence of an independent tradition of paperfolding in China, as well as in Germany, Italy and Spain among other places. However, because of the problems associated with preserving origami, there is very little direct evidence of its age or origins, aside from references in published material.

In China, traditional funerals include burning folded paper, most often representations of gold nuggets (yuanbao). It is not known when this practice started, but it seems to have become popular during the Sung Dynasty (905–1125 CE).[2] The paper folding has typically been of objects like dishes, hats or boats rather than animals or flowers.[3]

The earliest evidence of paperfolding in Europe is a picture of a small paper boat in Tractatus de sphaera mundi from 1490. There is also evidence of a cut and folded paper box from 1440.[4] It is probable paperfolding in the west originated with the Moors much earlier,[5] it is not known if it was independently discovered or knowledge of origami came along the silk route.

In Japan, the earliest unambiguous reference to a paper model is in a short poem by Ihara Saikaku in 1680 which describes paper butterflies in a dream.[6] Origami butterflies were used during the celebration of Shinto weddings to represent the bride and groom, so paperfolding had already become a significant aspect of Japanese ceremony by the Heian period (794–1185) of Japanese history, enough that the reference in this poem would be recognized. Samurai warriors would exchange gifts adorned with noshi, a sort of good luck token made of folded strips of paper.

In the early 1900s, Akira Yoshizawa, Kosho Uchiyama, and others began creating and recording original origami works. Akira Yoshizawa in particular was responsible for a number of innovations, such as wet-folding and the Yoshizawa-Randlett diagramming system, and his work inspired a renaissance of the art form.[7] During the 1980s a number of folders started systematically studying the mathematical properties of folded forms, which led to a steady increase in the complexity of origami models, which continued well into the 1990s, after which some designers started returning to simpler forms.[8]

Techniques and materials

Techniques

Many origami books begin with a description of basic origami techniques which are used to construct the models. These include simple diagrams of basic folds like valley and mountain folds, pleats, reverse folds, squash folds, and sinks. There are also standard named bases which are used in a wide variety of models, for instance the bird base is an intermediate stage in the construction of the flapping bird.[9]

Origami paper

Almost any laminar material can be used for folding; the only requirement is that it should hold a crease.

Origami paper, often referred to as "kami" (Japanese for paper), is sold in prepackaged squares of various sizes ranging from 2.5 cm to 25 cm or more. It is commonly colored on one side and white on the other; however, dual coloured and patterned versions exist and can be used effectively for color-changed models. Origami paper weighs slightly less than copy paper, making it suitable for a wider range of models.

Normal copy paper with weights of 70–90 g/m2 can be used for simple folds, such as the crane and waterbomb. Heavier weight papers of (19–24&nb 100 g/m2 (approx. 25 lb) or more can be wet-folded. This technique allows for a more rounded sculpting of the model, which becomes rigid and sturdy when it is dry.

Foil-backed paper, just as its name implies, is a sheet of thin foil glued to a sheet of thin paper. Related to this is tissue foil, which is made by gluing a thin piece of tissue paper to kitchen aluminium foil. A second piece of tissue can be glued onto the reverse side to produce a tissue/foil/tissue sandwich. Foil-backed paper is available commercially, but not tissue foil; it must be handmade. Both types of foil materials are suitable for complex models.

Washi (和紙) is the traditional origami paper used in Japan. Washi is generally tougher than ordinary paper made from wood pulp, and is used in many traditional arts. Washi is commonly made using fibres from the bark of the gampi tree, the mitsumata shrub (Edgeworthia papyrifera), or the paper mulberry but also can be made using bamboo, hemp, rice, and wheat.

Artisan papers such as unryu, lokta, hanji, gampi, kozo, saa, and abaca have long fibres and are often extremely strong. As these papers are floppy to start with, they are often backcoated or resized with methylcellulose or wheat paste before folding. Also, these papers are extremely thin and compressible, allowing for thin, narrowed limbs as in the case of insect models.

Paper money from various countries is also popular to create origami with; this is known variously as Dollar Origami, Orikane, and Money Origami.

Tools

It is common to fold using a flat surface but some folders like doing it in the air with no tools especially when displaying the folding. Many folders believe no tool should be used when folding. However a couple of tools can help especially with the more complex models. For instance a bone folder allows sharp creases to be made in the paper easily, paper clips can act as extra pairs of fingers, and tweezers can be used to make small folds. When making complex models from origami crease patterns, it can help to use a ruler and ballpoint embosser to score the creases. Completed models can be sprayed so they keep their shape better, and of course a spray is needed when wet folding.

Types of origami

Action origami

Origami not only covers still-life, there are also moving objects; Origami can move in clever ways. Action origami includes origami that flies, requires inflation to complete, or, when complete, uses the kinetic energy of a person's hands, applied at a certain region on the model, to move another flap or limb. Some argue that, strictly speaking, only the latter is really "recognized" as action origami. Action origami, first appearing with the traditional Japanese flapping bird, is quite common. One example is Robert Lang's instrumentalists; when the figures' heads are pulled away from their bodies, their hands will move, resembling the playing of music.

Modular origami

Modular origami consists of putting a number of similar pieces together to form a complete model. Normally the individual pieces are simple but the final assembly may be tricky. Many of the modular origami models are decorative balls like kusudama, the technique differs though in that kusudama allows the pieces to be put together using thread or glue.

Chinese paper folding includes a style called 3D origami where large numbers of pieces are put together to make elaborate models. Sometimes paper money is used for the modules. This style originated from some Chinese refugees while they were detained in America and is also called Golden Venture folding from the ship they came on.

Wet-folding

Wet-folding is an origami technique for producing models with gentle curves rather than geometric straight folds and flat surfaces. The paper is dampened so it can be moulded easily, the final model keeps its shape when it dries. It can be used, for instance, to produce very natural looking animal models. Size, an adhesive that is crisp and hard when dry, but dissolves in water when wet and becoming soft and flexible, is often applied to the paper either at the pulp stage while the paper is being formed, or on the surface of a ready sheet of paper. The latter method is called external sizing and most commonly uses Methylcellulose, or MC, paste, or various plant starches.

Pureland origami

Pureland origami is origami with the restriction that only one fold may be done at a time, more complex folds like reverse folds are not allowed, and all folds have straightforward locations. It was developed by John Smith in the 1970s to help inexperienced folders or those with limited motor skills. Some designers also like the challenge of creating good models within the very strict constraints.

Origami Tessellations

This branch of origami is one that has grown in popularity recently. Tessellation refers to a collection of figures fill a plane with no gaps or overlaps. In origami tessellations, pleats are used to connect molecules such as twist folds together in a repeating fashion.

During the 1960s, Shuzo Fujimoto was the first to explore twist fold tessellations in any systematic way, coming up with dozens of patterns and establishing the genre in the origami mainstream. Around the same time period, Ron Resch patented some tessellation patterns as part of his explorations into kinetic sculpture and developable surfaces, although his work was not known by the origami community until the 1980s. Chris Palmer is an artist who has extensively explored tessellations after seeing the Zilij patterns in the Alhambra, and has found ways to create detailed origami tessellations out of silk. Robert Lang and Alex Bateman are two designers who use computer programs to create origami tessellations. The first American book on origami tessellations was just published by Eric Gjerde and the field has been expanding rapidly. There are numerous origami tessellation artists including Chris Palmer (U.S.), Eric Gjerde (U.S.), Polly Verity (Scotland), Joel Cooper (U.S.), Christine Edison (U.S.), Ray Schamp (U.S.), Roberto Gretter (Italy), Goran Konjevod (U.S.),and Christiane Bettens (Switzerland) that are showing works that are both geometric and representational.

Kirigami

Kirigami is a Japanese term for paper cutting. Cutting was often used in traditional Japanese origami, but modern innovations in technique have made the use of cuts unnecessary. Most origami designers no longer consider models with cuts to be origami, instead using the term Kirigami to describe them. This change in attitude occurred during the 1960s and 70s, so early origami books often use cuts, but for the most part they have disappeared from the modern origami repertoire; most modern books don't even mention cutting.[10]

Mathematics and technical origami

Mathematics and practical applications

The practice and study of origami encapsulates several subjects of mathematical interest. For instance, the problem of flat-foldability (whether a crease pattern can be folded into a 2-dimensional model) has been a topic of considerable mathematical study.

A number of technological advances have come from insights obtained through paper folding. For example, techniques have been developed for the deployment of car airbags and stent implants from a folded position.[12]

The problem of rigid origami ("if we replaced the paper with sheet metal and had hinges in place of the crease lines, could we still fold the model?") has great practical importance. For example, the Miura map fold is a rigid fold that has been used to deploy large solar panel arrays for space satellites.

Origami can be used to construct various geometrical designs not possible with Compass and straightedge constructions. For instance paper folding may be used for angle trisection and doubling the cube.

There are plans for an origami airplane to be launched from space. A prototype passed a durability test in a wind tunnel on March 2008, and Japan's space agency adopted it for feasibility studies.

Technical origami

Technical origami, also known as origami sekkei (折り紙設計), is a field of origami that has developed almost hand-in-hand with the field of mathematical origami. In the early days of origami, development of new designs was largely a mix of trial-and-error, luck and serendipity. With advances in origami mathematics however, the basic structure of a new origami model can be theoretically plotted out on paper before any actual folding even occurs. This method of origami design was developed by Robert Lang, Meguro Toshiyuki and others, and allows for the creation of extremely complex multi-limbed models such as many-legged centipedes, human figures with a full complement of fingers and toes, and the like.

The main starting point for such technical designs is the crease pattern (often abbreviated as CP), which is essentially the layout of the creases required to form the final model. Although not intended as a substitute for diagrams, folding from crease patterns is starting to gain in popularity, partly because of the challenge of being able to 'crack' the pattern, and also partly because the crease pattern is often the only resource available to fold a given model, should the designer choose not to produce diagrams. Still, there are many cases in which designers wish to sequence the steps of their models but lack the means to design clear diagrams. Such origamists occasionally resort to the Sequenced Crease Pattern (abbreviated as SCP) which is a set of crease patterns showing the creases up to each respective fold. The SCP eliminates the need for diagramming programs or artistic ability while maintaining the step-by-step process for other folders to see. Another name for the Sequenced Crease Pattern is the Progressive Crease Pattern (PCP).

Paradoxically enough, when origami designers come up with a crease pattern for a new design, the majority of the smaller creases are relatively unimportant and added only towards the completion of the crease pattern. What is more important is the allocation of regions of the paper and how these are mapped to the structure of the object being designed. For a specific class of origami bases known as 'uniaxial bases', the pattern of allocations is referred to as the 'circle-packing'. Using optimization algorithms, a circle-packing figure can be computed for any uniaxial base of arbitrary complexity. Once this figure is computed, the creases which are then used to obtain the base structure can be added. This is not a unique mathematical process, hence it is possible for two designs to have the same circle-packing, and yet different crease pattern structures.

As a circle encloses the minimum amount of area for a given perimeter, circle packing allows for maximum efficiency in terms of paper usage. However, other polygonal shapes can be used to solve the packing problem as well. The use of polygonal shapes other than circles is often motivated by the desire to find easily locatable creases (such as multiples of 22.5 degrees) and hence an easier folding sequence as well. One popular offshoot of the circle packing method is box-pleating, where squares are used instead of circles. As a result, the crease pattern that arises from this method contains only 45 and 90 degree angles, which makes for easier folding.

Origami-related computer programs

- Doodle: used to diagram all the steps and figures involved in the creation of a figure.

- Treemaker: useful in designing a figure.

- OriPa: a program for drawing up crease patterns. Allows one to see what a crease pattern looks like when folded.

Ethics

Copyright in origami designs and the use of models has become an increasingly important issue as the internet has made the sale and distribution of pirated designs very easy.[13] It is considered good ethics to always credit the original artist and the folder when displaying origami models. All commercial rights to designs and models are typically reserved by origami artists. Normally a person who folds a model using a legally obtained design can publicly display the model unless such rights are specifically reserved, however folding a design for money or commercial use of a photo for instance would require consent.[14]

Gallery

These pictures show examples of various types of origami.

-

Dollar bill elephant, an example of money-bill origami

-

Kawasaki cube, an example of an iso-area model

-

A wet-folded bull

-

A challenging miniature version of a paper crane

-

Two examples of modular origami

-

An example of origami bonsai

-

Smart Waterbomb using circular paper and curved folds

See also

References

- ^ Merali, Zeeya (June 17, 2011), "Origami Engineer Flexes to Create Stronger, More Agile Materials", Science, 332: 1376–1377

- ^ Laing, Ellen Johnston (2004). Up In Flames. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804734554.

- ^ Temko, Florence (1986). Paper Pandas and Jumping Frogs. p. 123. ISBN 0-8351-1770-7.

- ^ Donna Serena da Riva. "Paper Folding in 15th century Europe" (PDF).

- ^ "David Lister on Islamic Arab and Moorish Folding?". Britishorigami.info. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ Hatori Koshiro. "History of Origami". K's Origami. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ Margalit Fox (April 2, 2005). "Akira Yoshizawa, 94, Modern Origami Master". New York Times.

- ^ Lang, Robert J. "Origami Design Secrets" Dover Publications, 2003

- ^ Rick Beech (2009). The Practical Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Origami. Lorenz Books. ISBN 9780754819820.

- ^ Lang, Robert J. (2003). Origami Design Secrets. A K Peters. ISBN 1-56881-194-2.

- ^ The World of Geometric Toy, Origami Spring, August, 2007.

- ^ Cheong Chew and Hiromasa Suziki, Geometrical Properties of Paper Spring, repoted in Mamoru Mitsuishi, Kanji Ueda, Fumihiko Kimura, Manufacturing Systems and Technologies for the New Frontier (2008), p. 159.

- ^ Robinson, Nick (2008). Origami Kit for Dummies. Wiley. p. 36–38. ISBN 978-047075857-1.

- ^ "Origami Copyright Analysis+FAQ" (PDF). OrigamiUSA. 2008. p. 9.

Further reading

- Robert J. Lang. The Complete Book of Origami: Step-by-Step Instructions in Over 1000 Diagrams. Dover Publications, Mineola, NY. Copyright 1988 by Robert J. Lang. ISBN 0-486-25837-8 (pbk.)

- Pages 1–30 are an excellent introduction to basic origami moves and notations. Each of the first 13 models is designed to allow the reader to practice one skill several times. Many models are folded from non-square paper.

- Kunihiko Kasahara. Origami Omnibus: Paper Folding for Everybody. Japan Publications, inc. Tokyo. Copyright 1988 by Kunihiko Kasahara. ISBN 4-8170-9001-4

- A book for a more advanced origamian; this book presents many more complicated ideas and theories, as well as related topics in geometry and culture, along with model diagrams.

- Kunihiko Kasahara and Toshie Takahama. Origami for the Connoisseur. Japan Publications, inc. Tokyo. Copyright 1987 by Kunihiko Kasahara and Toshie Takahama. ISBN 0-87040-670-1

- Satoshi Kamiya. Works by Satoshi Kamiya, 1995–2003. Origami House, Tokyo. Copyright 2005 by Satoshi Kamiya.

- An extremely complex book for the elite origamian, most models take 100+ steps to complete. Includes his famous Divine Dragon Bahamut and Ancient Dragons. Instructions are in Japanese and English.

- Issei Yoshino. Issei Super Complex Origami. Origami House, Tokyo.

- Contains many complex models, notably his Samurai Helmet, Horse, and multimodular Triceratops skeleton. Instructions are in Japanese.

- One Thousand Paper Cranes: The Story of Sadako and the Children's Peace Statue by Takayuki Ishii, ISBN 0-440-22843-3

- Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes by Eleanor Coerr, ISBN 0-698-11802-2

- Extreme Origami, Kunihiko Kasahara, 2001, ISBN 0-8069-8853-3

- Ariomar Ferreira da Silva. Brincando com Origami Arquitetônico: 16 diagrams. Global Editora, São Paulo, Brazil. Copyright 1991 by Ariomar Ferreira da Silva and Leôncio de O. Carvalho. ISBN 85-260-0273-2

- Masterworks of Paper Folding by Michael LaFosse

- Papercopia: Origami Designs by David Shall, 2008 ISBN 978-0-9796487-0-0. Contains diagrams for 24 original models by the author including Claw Hammer, Daffodil, Candlestick.

- Nick Robinson. Origami For Dummies. John Wiley, Copyright 2008 by Nick Robinson. ISBN 0470758570. An excellent book for beginners, covering many aspects of origami overlooked by other books.

- Nick Robinson. Encyclopedia of Origami. Quarto, Copyright 2004 by Nick Robinson. ISBN 1-84448-025-9. An book full of stimulating designs.

- Linda Wright. Toilet Paper Origami: Delight Your Guests with Fancy Folds and Simple Surface Embellishments. Copyright 2008 by Lindaloo Enterprises, Santa Barbara, CA. ISBN 9780980092318.

External links

- Free Origami Instruction Database !, a collection of links to free origami instructions, pictures and videos.

- OrigamiTube.com Watch, Fold, Show Off! Collection of origami instructional and origami related videos.

- Origami Nut Original instructional videos of origami folding with diagrams and varying difficulty levels.

- Origami.com, collection of diagrams, suitable for beginners.

- GiladOrigami.com, contains a large gallery.

- Paper Circle: Origami Out of Hand – Exhibition by Origami artists Tomoko Fuse, Robert J. Lang, and David and Assia Brill of Great Britain.

- The Fold, a large collection of diagrams.

- WikiHow on How to Make Origami

- Origami.org.uk, 3D animated origami diagrams of peace crane and flapping bird.

- Origami Surprise !, a brand new type of origami folding instructions.

- Between the Folds Documentary film featuring 15 international origami practitioners

- Interview with Robert Lang at Institute for Advanced Study, University of Minnesota, March, 2011