Dissociative identity disorder

| Dissociative identity disorder | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, psychology |

| Frequency | 1.5% (United States of America) |

Dissociative identity disorder (DID), also known as multiple personality disorder,[1] is a mental disorder characterized by at least two distinct and relatively enduring identities or dissociated personality states that alternately control a person's behavior, and is accompanied by memory impairment for important information not explained by ordinary forgetfulness. These symptoms are not accounted for by substance abuse, seizures, other medical condition or fantasy behavior in children.[2] Diagnosis is often difficult as there is considerable comorbidity with other mental disorders. Malingering should be ruled out if there is possible financial or forensic gain, as well as factitious disorder if help-seeking behavior is prominent.[2]

There is little systematic data on the prevalence of DID.[3] Some evidence indicates a prevalence rate of between 1 and 3% in the general population, and between 1 and 5% in inpatient groups in Europe and North America.[4] It is diagnosed more frequently in North America than in the rest of the world, and is 5 to 9 times more common in females than males.[5][6][7]

Traditionally dissociative disorders such as DID were attributed to trauma and other forms of stress that caused memory to separate or dissociate, among other symptoms, but research on this hypothesis has been characterized by poor methodology. So far, experimental studies, usually focusing on memory, have been few and the research has been inconclusive.[8] It became a popular diagnosis in the 1970s but it is unclear if the actual incidence of the disorder increased or only its popularity. An alternative hypotheses for its etiology is that DID is a product of techniques employed by some therapists.

DID is one of the most controversial psychiatric disorders with no clear consensus regarding its diagnosis or treatment.[9] Research on treatment effectiveness still focuses mainly on clinical approaches and case studies. No systematic, empirically-supported approach exists. DID rarely resolve spontaneously, and symptoms vary over time.[10] In general, the prognosis is poor, especially for those with co-morbid disorders.

Signs and symptoms

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria for DID include "the presence of two or more distinct identities or personality states". At least two take control of the individual's behavior on a recurrent basis, accompanied by inability to recall personal information beyond what is expected through normal forgetfulness. The diagnosis excludes symptoms caused by alcohol, drugs or medications and other medical conditions such as complex partial seizures and normal fantasy play in children.[2] Daily functioning can vary from severely impaired to normal to "highly effective".[11] Other features that may be essential to the condition include chronic depersonalization and derealization, disturbances with memory, identity confusion and auditory hallucinations that seem to come from inside the patient's own head. The clinical presentation, level of symptom severity and level of daily functioning varies widely.[12] The symptoms of dissociation serve to reduce distress and act as a form of coping, and due to the interference of dissociative symptoms with memory and functioning individuals with DID may experience distress at the consequences of DID rather than the symptoms themselves.[13]

Co-morbid mental illnesses are the rule rather than the exception in all dissociative disorder cases, with 82% of DID patients being diagnosed with at least one other DSM Axis I diagnosis in their lifetime.[14] Common Axis I co-morbidities include anxiety disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (up to 80%), social phobia (up to 75%), panic disorder (54-70%) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (up to 64%); mood disorders such as major depressive disorder (88-97%); substance-related disorders (50-65%); eating disorders such as bulimia nervosa (19-23%); and somatoform disorders (23–45%).[15] In addition, a majority of those diagnosed with DID meet the criteria for borderline personality disorder,[16] a significant minority meet the criteria for avoidant personality disorder, and other personality disorders are not uncommon.[14] Contrary to what would be expected by the presence of Schneiderian first-rank symptoms (auditory hallucinations or "hearing voices"), dissociative disorders only rarely appear in co-morbidity with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.[16] Individuals diagnosed with DID also demonstrate the highest hypnotizability of any clinical population.[13]

Despite research on DID including structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, single-photon emission computed tomography, event-related potential and electroencephalography, no convergent neuroimaging findings have been identified regarding DID, making it difficult to hypothesize a biological basis for DID. In addition, many of the studies that do exist were performed from an explicitly trauma-based position, and did not consider the possibility of iatrogenic induction of DID. There is no research to date regarding the neuroimaging and introduction of false memories in DID patients,[9] though there is evidence of changes in visual parameters[17] and support for amnesia between alters.[18][9] DID patients also appear to show deficiencies in tests of conscious control of attention and memorization (which also showed signs of compartmentalization for implicit memory between alters but no such compartmentalization for verbal memory) and increased and persistent vigilance and startle responses to sound. DID patients may also demonstrate altered neuroanatomy.[16]

Several of the terms used to diagnose DID (personality, ego state, identity and even amnesia) are undefined[18] though psychiatrist Paulette Gillig draws distinction between an "ego state" (behaviors and experiences united by a common principle but possessing permeable boundaries with other such states) and the commonly used term "alters" (which have a separate autobiographical memory, independent initiative and sense of ownership over their own actions) described in DID.[16] Ellert Nijenhuis and colleagues suggest a distinction between personalities responsible for day-to-day functioning (associated with blunted physiological responses and reduced emotions) and those emerging in survival situations (involving Fight or Flight reflexes, vivid traumatic memories and strong, painful emotions).[19]

Since many dissociative symptoms are based on self report and not observable to the clinician, patients are often disinclined to seek treatment, especially since their symptoms may not be taken seriously; thus dissociative disorders have been referred to as "diseases of hiddenness".[20]

Causes

The cause of DID is controversial, with debate occurring between the developmental trauma and iatrogenic/sociocognitive hypothesis. Questions to propose which is correct include whether the condition is equally prevalent in and out of therapy, whether diagnostic clusters are due to inappropriate techniques or greater clinician awareness of the condition and prevalence rates across cultures; these questions remain largely unanswered.[21]

Developmental trauma

People diagnosed with DID often report that they have experienced severe physical and sexual abuse, especially during early to mid childhood.[2] They also report more historical psychological trauma than those diagnosed with any other mental illness.[22] Severe sexual, physical, or psychological trauma in childhood by a primary caregiver has been proposed as an explanation for the development of DID. In this theory, awareness, memories and feelings of a harmful action or event caused by the caregiver is pushed into the subconscious and dissociation becomes a coping mechanism for the individual during times of stress. These memories and feelings are later experienced as a separate entity, and if this happens multiple times, multiple alters are created.[23] Those who accept the validity of DID as a diagnosis attribute it to extremes of stress or disorders of attachment. What may be expressed as posttraumatic stress disorder in adults may become DID when found in children, possibly due to their greater use of imagination as a form of coping.[13][16] Possibly due to developmental changes and a more coherent sense of self past the age of six, the experience of extreme trauma may result in different, though also complex dissociative symptoms and identity disturbances.[13] A specific relationship of childhood abuse, disorganized attachment and lack of social support are thought to be a necessary component of DID, along with a rigid parenting style, temperament, genetic predisposition and an inversion of the parent-child relationship.[16] Other suggested explanations include insufficient childhood nurturing combined with the innate ability of children in general to dissociate memories or experiences from consciousness.[11] A high percentage of patients report child abuse[2][24] and others report an early loss, serious medical illness or other traumatic events.[11]

Psychiatrists August Piper and Harold Merskey have challenged the trauma hypothesis, arguing that correlation does not imply causation - the fact that DID patients report childhood trauma does not mean trauma causes DID - and point to the rareness of the diagnosis before 1980 as well as a failure to find DID as an outcome in longitudinal studies of traumatized children. They assert that DID cannot be accurately diagnosed because of vague and unclear diagnostic criteria in the DSM and undefined concepts such as "personality state" and "identities", and question the evidence for childhood abuse in patients beyond self-reports, the lack of definition of what would indicate a threshold of abuse sufficient to induce DID and the extremely small number of cases of children diagnosed with DID despite an average age of appearance of the first alter of three years.[25] Psychiatrist Colin Ross disagrees with Piper and Merskey's conclusion that DID cannot be accurately diagnosed, pointing to internal consistency between different structured dissociative disorder interviews (including the Dissociative Experiences Scale, Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule and Structured Clinical Interview for Dissociative Disorders)[18] that are in the internal validity range of widely accepted mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and major depressive disorder. In his opinion, Piper and Merskey are setting the standard of proof higher than they are for other diagnoses. He also asserts that Piper and Merskey have cherry-picked data and not incorporated all relevant scientific literature available, such as independent corroborating evidence of trauma in some patients.[26]

Therapist induced

It has been suggested that symptoms of DID may be created by therapists using techniques to "recover" memories with suggestible patients (such as the use of hypnosis to "access" alters, facilitate age regression or retrieve memories).[27][28][12][25][21] Referred to as the "sociocognitive model" (SCM), it suggests that DID is due to patients are consciously or unconsciously enacting social roles expected of people with their diagnosis.[21] The characteristics of patients diagnosed with DID (hypnotizability, suggestibility, frequent fantasization and mental absorption) contributed to these concerns and concerns regarding the validity of recovered memories.[20] Skeptics believe that a small subset of doctors are responsible for diagnosing the majority of individuals with DID.[28][25] Psychologist Nicholas Spanos and others skeptical of the condition have suggested that in addition to iatrogenesis, DID may be the result of role-playing rather than separate personalities, though others disagree, pointing to a lack of incentive to manufacture or maintain separate personalities and point to the claimed histories of abuse of these patients.[29] Piper and Merskey list a variety of arguments for the iatrogenic position, including the lack of children diagnosed with DID, the sudden spike in incidence after 1980 in the absence of evidence of greater rates of child abuse, the appearance of the disorder almost exclusively in individuals undergoing psychotherapy (particularly involving hypnosis), an increase in the number of alters over time and the changes in the identity of alters (such as those claiming to be animals or mythological creatures).[25] Psychiatrist Numan Gharaibeh suggests proponents of the traumagenic hypothesis face three possible conflicts of interest in rejecting the iatrogenic hypothesis - financial (Gharaibeh estimated a single patient could provide for an annual reimbursement rate of $20,000 in the United States), the recognition of "false expertise", and the need to believe in the disorder in order to become a recognized expert in the condition.[30]

The iatrogenic position is strongly linked to ideas about false memories. There is little consensus between the iatrogenic and traumagenic positions regarding DID and debates are both passionate and diametrically opposed.[9] Proponents of the iatrogenic position suggest a small number of clinicians diagnosing a disproportionate number of cases would provide evidence for their position[21] though it has also been claimed that higher rates of diagnosis in specific countries like the United States may be due to greater awareness of DID and lower rates in other countries may be due to an artificially low recognition of the diagnosis.[12]

In children

The fact that DID is extremely rare in actual children is cited as a reason to doubt the validity of DID, and proponents of both etiologies believe that the discovery of DID in a child that had never undergone treatment would critically undermine the SCM. Conversely the development of DID only after undergoing treatment would challenge the traumagenic model.[21] To date approximately 250 cases of DID in children have been identified, though the data does not offer unequivocal support for either theory. While children have been diagnosed with DID before therapy, several were presented to clinicians by parents with the diagnosis; others were influenced by the appearance of DID in popular culture or due to a diagnosis of psychosis due to hearing voices - a symptom also found in DID. No studies have looked for children with DID in the general population, and the single study that attempted to look for children with DID not already in therapy did so by examining siblings of those already in therapy for DID. An analysis of diagnosis of children reported in scientific publications, 44 case studies of single patients were found to be evenly distributed (i.e. each case study was reported by a different author) but in articles regarding groups of patients, four researchers were responsible for the majority of the reports.[21]

Diagnosis

The American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) diagnoses DID according to the diagnostic criteria found in in section 300.14 (dissociative disorders). The criteria require that an adult, for non-physiological reasons, be recurrently controlled by two or more discrete identities or personality states, accompanied by memory lapses for important information.[2] While otherwise similar, the diagnostic criteria for children also rules out fantasy. Diagnosis is normally performed by a clinically trained mental health professional such as a psychiatrist or psychologist through clinical evaluation, interviews with family and friends, and consideration of other ancillary material. Specially designed interviews (such as the SCID-D) and personality assessment tools may be used in the evaluation as well.[31] Since most of the symptoms depend on self report and are not concrete and observable, the result is a degree of subjectivity in making the diagnosis.[18]

The psychiatric history frequently but not always contains multiple previous diagnoses of various mental disorders and treatment failures.[31] The diagnosis has been criticized as proponents of the iatrogenic or sociocognitive hypothesis believe it as a culture-bound and often iatrogenic condition which they believe is in decline.[27][25][21] Other researchers disagree and argue that the condition is real and supported by convergent evidence and its inclusion in the DSM is supported by reliable and convergent evidence, with diagnostic criteria allowing it to be clearly discriminated from conditions it is often mistaken for (schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder and seizure disorder).[12] Since a large proportion of cases are diagnosed by specific clinicians suggests to some that either those clinicians are indeed responsible for the iatrogenic creation of alters or there is a high rate of false positives due to subjective diagnostic criteria, though proponents of the traumagenic hypothesis believe there are valid and objective diagnostic criteria to identify individuals with DID.[21]

Screening

Perhaps due to their perceived rarity, the dissociative disorders (including DID) were not initially included in the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), which is designed to make psychiatric diagnoses more rigorous and reliable.[18] Instead, shortly after the publication of the initial SCID a freestanding protocol for dissociative disorders (SCID-D)[32] was published.[18] This interview takes about 30 to 90 minutes depending on the subject's experiences.[33] An alternative diagnostic instrument, the Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule, also exists but the SCID-D is generally considered superior.[18] The Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule (DDIS)[34] is a highly structured interview that discriminates among various DSM-IV diagnoses. The DDIS can usually be administered in 30–45 minutes.[35]

Other questionnaires include the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES), Perceptual Alterations Scale, Questionnaire on Experiences of Dissociation, Dissociation Questionnaire and the Mini-SCIDD. All are strongly intercorrelated and except the Mini-SCIDD, all incorporate absorption, a normal part of personality involving narrowing or broadening of attention.[18] The DES[36] is a simple, quick, and validated[37] questionnaire that has been widely used to screen for dissociative symptoms, with variations for children and adolescents. Tests such as the DES provide a quick method of screening subjects so that the more time-consuming structured clinical interview can be used in the group with high DES scores. Depending on where the cutoff is set, people who would subsequently be diagnosed can be missed. An early recommended cutoff was 15-20.[38] The reliability of the DES in non-clinical samples has been questioned.[39]

Differential diagnoses

Studies have shown that DID patients are diagnosed with five to seven co-morbid disorders on average - much higher than other mental illnesses.[16] Due to overlap between symptoms, differential diagnosis between DID and a variety of other conditions (including schizophrenia, psychosis, normal and rapid-cycling bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, somatization and personality disorders) can be complicated as delusions or auditory hallucinations can be mistaken for speech by other personalities and vice-versa (individuals with DID may also conceal these symptoms and avoid disclosing them during interviews to avoid being considered "crazy" or out of feelings of shame[13]), or sudden behavior changes being attributed to sudden mood fluctuations. Persistence and consistency of identities and behavior, amnesia, measures of dissociation or hypnotizability and reports from family members or other associates indicating a history of such changes can help distinguish DID from other conditions. A diagnosis of DID takes precedence over any other dissociative disorders. Distinguishing true DID from malingering is a concern when financial or legal gains are an issue, and factitious disorder may also be considered if there patient has a history or pattern help or attention seeking. Individuals who state that their symptoms are due to external spirits or entities entering their bodies are generally diagnosed with dissociative disorder not otherwise specified rather than DID due to the lack of internal personalities or alter states.[2] Most individuals who enter an emergency department and are unaware of their names are generally in a psychotic state rather dissociative. Auditory hallucinations are common, but complex visual hallucinations may also occur.[16] Though hallucinations can be experienced in any sensory system (visual, auditory, tactile, gustatory or olfactory),[13] patients generally have adequate reality testing to distinguish between reality and hallucinations, and lack the negative symptoms of schizophrenia.[12] In addition, individuals with psychosis are much less susceptible to hypnosis than those with DID.[13] Difficulties in differential diagnosis are increased in children.[21]

Conditions which may be present with similar symptoms include borderline personality disorder, and the dissociative conditions of dissociative amnesia and dissociative fugue.[40] The clearest distinction is the lack of discrete formed personalities in these conditions. Individuals with schizophrenia will have some form of delusions, hallucinations or thought disorder.[40] The condition may be under-diagnosed due to skepticism and lack of awareness from mental health professionals, made difficult due to the lack of specific and reliable criteria for diagnosing DID as well as a lack of prevalence rates due to the failure to examine systematically selected and representative populations.[28][41] A specific relationship between DID and borderline personality disorder has been posited several times, with various clinicians noting significant overlap between symptoms and patient behaviors and it has been suggested that DID may arise "from a substrate of borderline traits." Reviews of DID patients and their medical records concluded that the majority of those diagnosed with DID would also meet the criteria for either borderline personality disorder or more generally borderline personality.[16]

History of the diagnosis

The DSM-II used the term Hysterical Neurosis, Dissociative Type. The DSM-III grouped the diagnosis with the other four major dissociative disorders using the term "multiple personality disorder". The DSM-IV made more changes to DID than any other dissociative disorder,[12] and renamed it DID.[2] The name was changed for two reasons. First, to emphasize the main problem was not a multitude of personalities, but rather a lack of a single, unified identity[12] and an emphasis on "the identies as centers of information processing".[13] Second, the term "personality" is used to refer to "characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, moods and behaviors of the whole individual", while for a patient with DID, the switches between identities and behavior patterns is the personality.[12] It is for this reason the DSM-IV-TR referred to "distinct identities or personality states" instead of personalities. The diagnostic criteria also changed to indicate that while the patient may name and personalize alters, they lack an independent, objective existence.[12] The changes also included the addition of amnesia as a symptom, which was not included in the DSM-III-R because despite being a core symptom of the condition, patients may experience "amnesia for the amnesia" and fail to report it.[13] Amnesia was replaced when it became clear that the risk of false negative diagnoses was low because amnesia was central to DID.[12]

The ICD-10 places the diagnosis in the category of "dissociative disorders", within the subcategory of "other dissociative (conversion) disorders", but continues to list the condition as multiple personality disorder.[1]

Proposed changes for the DSM-5

The DSM-IV-TR criteria for DID have been criticized for failing to capture the clinical complexity of DID, lacking usefulness in diagnosing individuals with DID (for instance, by focussing on the two least frequent and most subtle symptoms of DID) producing a high rate of false negatives and an excessive number of DDNOS diagnoses, for excluding possession (seen as a cross-cultural form of DID), and for including only two "core" symptoms of DID (amnesia and self-alteration) while failing to discuss hallucinations, trance-like states, somatoform, depersonalization and derealization symptoms. Arguments have been made for allowing diagnosis through the presence of some, but not all of the characteristics of DID rather than the current exclusive focus on the two least common and noticeable features.[13] The DSM-V-TR criteria has also been criticized for being tautological, using imprecise and undefined language and for the use of instruments that give a false sense of validity and empirical certainty to the diagnosis.[30]

The proposed diagnostic criteria for DID in the DSM-5 are:[42]

- Disruption of identity characterized by two or more distinct personality states (one can be the host) or an experience of possession, as evidenced by discontinuities in sense of self, cognition, behavior, affect, perceptions, and/or memories. This disruption may be observed by others, or reported by the patient.

- Inability to recall important personal information, for everyday events or traumatic events, that is inconsistent with ordinary forgetfulness.

- Causes clinically significant distress and impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

- The disturbance is not a normal part of a broadly accepted cultural, religious practice, or part of the normal fantasy play of children.

- The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., blackouts or chaotic behavior during alcohol intoxication) or a general medical condition (e.g., complex partial seizures).

The proposed revision will also include specifiers for "prominent non-epileptic seizures and/or other sensory-motor (functional neurologic) symptoms" due to the high number of DID patients with conversion or somatoform symptoms that may require clarification or special treatment.

The proposed Criterion C is intended to "help differentiate normative cultural experiences from psychopathology." This phrase, which occurs in several other diagnostic criteria, is proposed for inclusion in 300.14 as part of a proposed merger of dissociative trance disorder with DID. For example, professionals would be able to take shamanism, which involves voluntary possession trance states, into consideration, and not have to diagnose those who report it as having a mental disorder.[43][44]

Treatment

There is a general lack of consensus in the diagnosis and treatment of DID[9] and research on treatment effectiveness still focuses mainly on clinical approaches and case studies. General treatment guidelines exist that suggest a phased, eclectic approach with more concrete guidance and agreement on early stages but no systematic, empirically-supported approach exists and later stages of treatment are not well described or agreed-upon. Even highly experienced therapists have few patients that achieve a unified identity.[45] Common treatment methods include an eclectic mix of psychotherapy techniques, including cognitive behavioral (CBT),[16] insight-oriented therapies,[18] dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), hypnotherapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR). Medications can be used for co-morbid disorders and/or targeted symptom relief.[4][20] Some behavior therapists initially use behavioral treatments such as only responding to a single identity, and then use more traditional therapy once a consistent response is established.[46] Brief treatment due to managed care may be difficult, as individuals diagnosed with DID may have unusual difficulties in trusting a therapist and take a prolonged period to form a comfortable therapeutic alliance.[4] Regular contact (weekly or biweekly) is more common, and treatment generally lasts years - not weeks or months.[4][16]

Therapy for DID is generally phase oriented. Different alters may appear based on their greater ability to deal with specific situational stresses or threats. While some patients may initially present with a large number of alters, this number may reduce during treatment - though it is considered important for the therapist to become familiar with at least the more prominent personality states as the "host" personality may not be the "true" identity of the patient. Specific alters may react negatively to therapy, fearing the therapists goal is to eliminate the alter (particularly those associated with illegal or violent activities). A more realistic and appropriate goal of treatment is to integrate adaptive responses to abuse, injury or other threats into the overall personality structure.[16] There is debate over issues such as whether exposure therapy (reliving traumatic memories, also known as abrecation), engagement with alters and physical contact during therapy is appropriate and there are clinical opinions both for and against each option with little high-quality evidence for any position. In general clinicians believe exposure therapy to be important and useful in later stages of treatment and touching is normally not helpful due to patients having negative associations with physical contact or the creation of issues with personal boundaries.[45]

The International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation has published guidelines to phase-oriented treatment in adults as well as children and adolescents that are widely used in the field of DID treatment.[4][45] The first phase of therapy focuses on symptoms and relieving the distressing aspects of the condition, ensuring the safety of the individual, improving the patient's capacity to form and maintain healthy relationships, and improving general daily life functioning. Co-morbid disorders such as substance abuse and eating disorders are addressed in this phase of treatment.[4] The second phase focuses on stepwise exposure to traumatic memories and prevention of re-dissociation. The final phase focuses on reconnecting the identities of disparate alters into a single functioning identity with all its memories and experiences intact.[4] Movement through the phases is often non-linear; patients in the second or third phase of treatment may need to go back to a previous phase to maintain safety and/or process previously unprocessed material.[47]

Prognosis

The person with DID is likely to hide symptoms exhibiting what R. Kluft called "pathology of hiddenness", a sign attributed to various factors including a lack of unawareness - thinking everyone is like them and shame and fear of abusers (even after the abusers have died) is very real to those with DID. [48] Generally, the earlier one is diagnosed the better the prognosis and even greater if diagnosis and treatment is obtained during childhood. Left untreated it is a chronic and recurrent disorder. [49] Prognosis becomes far less optimistic if not appropriately treated. {citation needed} Successful treatment (psychotherapy) for adults usually takes years depending on ones goals; to operate as a unified self and free of the effects of DID or they might choose to become coconscious and still have DID. {citation needed} If the typical 3 phase treatment for DID is completed, dissociative boundaries are reduced resulting in a unified self and elimination of the effects and symptoms of trauma memories. Therapy is not easy and hospitalization can be required for some patients. This chronic disorder rarely resolves spontaneously if ever. [10] [50] Individuals with primarily dissociative symptoms and features of posttraumatic stress disorder normally recover with treatment. [11] Many patients have a reported history of being sexually abused as a child [51] and often cope by abusing alcohol or other substances - a negative way of coping with their victimization. [11] Those with co-morbid addictions, personality, mood, or eating disorders face a longer, slower, and more complicated recovery process. [11] Individuals still attached to abusers face the poorest prognosis. [11] Treatment may be long-term - and consist solely of symptom relief rather than integration. [11] Changes in identity, loss of memory, and awaking in unexplained locations and situations often leads to chaotic personal lives. Parenting is difficult prior to sucessful treatment. [52] Individuals with the condition commonly have histories of failed suicide attempts and self-harm. [22][53][54]

Epidemiology

There is little systematic data on the prevalence of DID.[3] It occurs more commonly in young adults[3] and declines with age.[55] Reported rates in the community vary from 1% to 3% with higher rates among psychiatric patients.[56][4] It is 5 to 9 times more common in females than males during young adulthood.[7] In children rates among females and males are neither the same (5:4).[10]

Though the condition has been described in non-English speaking nations and non-Western cultures, these reports all occur in English-language journals authored by international researchers who cite Western scientific literature and are therefore not isolated from Western influences.[21]

DID diagnoses are extremely rare in children; much of the research on childhood DID occurred in the 1980s and 1990s and does not address ongoing controversies surrounding the diagnosis.[21]

Changing prevalence

Rates of diagnosed DID have been increasing.[10] Initially DID along with the rest of the dissociative disorders were considered the rarest of psychological conditions, numbering less than 100 by 1944, with only one further case added in the next two decades.[18] In the late 1970s and 80s, the number of diagnoses rose sharply.[18] Estimate from the 1980s where 0.01%.[10] Accompanying this rise was an increase in the number of alters, rising from only the primary and one alter personality in most cases, to an average of 13 in the mid-1980s (the increase in both number of cases and number of alters within each case are both factors in professional skepticism regarding the diagnosis).[18] Others explain the increase as being due to the use of inappropriate therapeutic techniques in highly suggestible individuals, though this is itself controversial.[28][29] Figures from psychiatric populations (inpatients and outpatients) show a wide diversity from different countries:[57]

North America

The DSM does not provide an estimate of incidence for DID and dissociative disorders were excluded from the Epidemiological Catchment Area Project. As a result, there are no national statistics for incidence and prevalence of DID in the United States.[18]

DID is a controversial diagnosis and condition, with much of the literature on DID still being generated and published in North America, to the extent that it was once regarded as a phenomenon confined to that continent[6][27] though research has appeared discussing the appearance of DID in other countries and cultures.[58] A 1996 review offered three possible causes for the sudden increase in people diagnosed with DID:[5]

- The result of therapist suggestions to suggestible people, much as Charcot's hysterics acted in accordance with his expectations.

- Psychiatrists' past failure to recognize dissociation being redressed by new training and knowledge.

- Dissociative phenomena are actually increasing, but this increase only represents a new form of an old and protean entity: "hysteria".

Paris believes that the first possible cause is the most likely. Etzel Cardena and David Gleaves believe the over-representation of DID in North America is the result of increased awareness and training about the condition which had formerly been missing.[12]

History

Before the 19th century, people exhibiting symptoms similar to those were believed to be possessed.[53] The first case of DID was thought to be described by Paracelsus in 1646.[59]

An intense interest in spiritualism, parapsychology, and hypnosis continued throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries,[6] running in parallel with John Locke's views that there was an association of ideas requiring the coexistence of feelings with awareness of the feelings.[60] Hypnosis, which was pioneered in the late 18th century by Franz Mesmer and Armand-Marie Jacques de Chastenet, Marques de Puységur, challenged Locke's association of ideas. Hypnotists reported what they thought were second personalities emerging during hypnosis and wondered how two minds could coexist.[6]

The 19th century saw a number of reported cases of multiple personalities which Rieber[60] estimated would be close to 100. Epilepsy was seen as a factor in some cases,[60] and discussion of this connection continues into the present era.[61][62]

By the late 19th century there was a general acceptance that emotionally traumatic experiences could cause long-term disorders which might display a variety of symptoms.[63] These conversion disorders were found to occur in even the most resilient individuals, but with profound effect in someone with emotional instability like Louis Vivé (1863-?) who suffered a traumatic experience as a 13-year-old when he encountered a viper. Vivé was the subject of countless medical papers and became the most studied case of dissociation in the 19th century.

Between 1880 and 1920, many great international medical conferences devoted a lot of time to sessions on dissociation.[64] It was in this climate that Jean-Martin Charcot introduced his ideas of the impact of nervous shocks as a cause for a variety of neurological conditions. One of Charcot's students, Pierre Janet, took these ideas and went on to develop his own theories of dissociation.[65] One of the first individuals diagnosed with multiple personalities to be scientifically studied was Clara Norton Fowler, under the pseudonym Christine Beauchamp; American neurologist Morton Prince studied Fowler between 1898 and 1904, describing her case study in his 1906 monograph, Dissociation of a Personality.[65]

In the early 20th century interest in dissociation and multiple personalities waned for a number of reasons. After Charcot's death in 1893, many of his so-called hysterical patients were exposed as frauds, and Janet's association with Charcot tarnished his theories of dissociation.[6] Sigmund Freud recanted his earlier emphasis on dissociation and childhood trauma.[6]

In 1910, Eugen Bleuler introduced the term schizophrenia to replace dementia praecox. A review of the Index medicus from 1903 through 1978 showed a dramatic decline in the number of reports of multiple personality after the diagnosis of schizophrenia became popular, especially in the United States.[66] A number of factors helped create a large climate of skepticism and disbelief; paralleling the increased suspicion of DID was the decline of interest in dissociation as a laboratory and clinical phenomenon.[64]

Starting in about 1927, there was a large increase in the number of reported cases of schizophrenia, which was matched by an equally large decrease in the number of multiple personality reports.[64] Bleuler also included multiple personality in his category of schizophrenia. It was concluded in the 1980s that DID patients are often misdiagnosed as suffering from schizophrenia.[64]

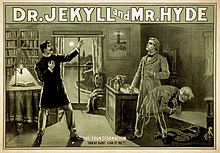

The public, however, was exposed to psychological ideas which took their interest. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and many short stories by Edgar Allan Poe had a formidable impact.[60] In 1957, with the publication of the book The Three Faces of Eve and the popular movie which followed it, the American public's interest in multiple personality was revived. During the 1970s an initially small number of clinicians campaigned to have it considered a legitimate diagnosis.[64]

Between 1968 and 1980 the term that was used for dissocative identity disorder was "Hysterical neurosis, dissociative type". The APA wrote in the second edition of the DSM: "In the dissociative type, alterations may occur in the patient's state of consciousness or in his identity, to produce such symptoms as amnesia, somnambulism, fugue, and multiple personality."[67] The number of cases sharply increased in the late 1970s and throughout the 80s, and the first scholarly monographs on the topic appeared in 1986.[18]

In 1974 the highly influential book Sybil was published, and later made into a miniseries in 1976 and again in 2007. Describing what Robert Rieber called “the third most famous of multiple personality cases”,[68] it presented a detailed discussion of the problems of treatment of “Sybil”, a pseudonym for Shirley Ardell Mason. Though the book and subsequent films helped popularize the diagnosis, later analysis of the case suggested different interpretations, ranging from Mason’s problems being iatrogenically induced through therapeutic methods used by her psychiatrist, Cornelia B. Wilbur or an inadvertent hoax due in part to the lucrative publishing rights,[68][69] though this conclusions has itself been challenged.[70] As media attention on DID increased, so too did the controversy surrounding the diagnosis.[59]

With the publication of the DSM-III, which omitted the terms "hysteria" and "neurosis" (and thus the former categories for dissociative disorders), dissociative diagnoses became "orphans" with their own categories[71] with dissociative identity disorder appearing as "multiple personality disorder".[18] In the opinion of McGill University psychiatrist Joel Paris, this inadvertently legitimized them by forcing textbooks, which mimicked the structure of the DSM, to include a separate chapter on them and resulted in an increase in diagnosis of dissociative conditions. Once a rarely occurring spontaneous phenomena (research in 1944 showed only 76 cases),[72] became "an artifact of bad (or naïve) psychotherapy" as patients capable of dissociating were accidentally encouraged to express their symptoms by "overly fascinated" therapists.[71]

"Interpersonality amnesia" was removed as a diagnostic feature from the DSM III in 1987, which may have contributed to the increasing frequency of the diagnosis.[18] There were 200 reported cases of DID as of 1980, and 20,000 from 1980 to 1990.[73] Joan Acocella reports that 40,000 cases were diagnosed from 1985 to 1995.[74] Scientific publications regarding DID peaked in the mid-1990s then rapidly declined.[75]

In 1994, the fourth edition of the DSM replaced the criteria again and changed the name of the condition from "multiple personality disorder" to the current "dissociative identity disorder" to emphasize the importance of changes to consciousness and identity rather than personality. The inclusion of interpersonality amnesia helped to distinguish DID from dissociative disorder not otherwise specified, but the condition retains an inherent subjectivity due to difficulty in defining terms such as personality, identity, ego-state and even amnesia.[18] The ICD-10 still classifies DID as a "Dissociative [conversion] disorder" and retains the name "multiple personality disorder" with the classification number of F44.8.81.[1]

A 2006 study compared scholarly research and publications on DID and dissociative amnesia to other mental health conditions, such as anorexia nervosa, alcohol abuse and schizophrenia from 1984 to 2003. The results were found to be unusually distributed, with a very low level of publications in the 1980s followed by a significant rise that peaked in the mid-1990s and subsequently rapidly declined in the decade following. Compared to 25 other diagnosis, the mid-90's "bubble" of publications regarding DID was unique. In the opinion of the authors of the review, the publication results suggest a period of "fashion" that waned, and that the two diagnoses "[did] not command widespread scientific acceptance".[75]

Society and culture

Despite its rareness, DID is portrayed with remarkable frequency in popular culture, producing or appearing in numerous books, films and television shows.[29]

Psychiatrist Colin A. Ross has stated that based on documents obtained through freedom of information legislation, psychiatrists linked to Project MKULTRA claimed to be able to deliberately induce dissociative identity disorder using a variety of aversive techniques.[77]

Surveys of the attitudes of Canadian and American psychiatrists' attitudes towards dissociative disorders completed in 1999[78] and 2001[79] found considerable skepticism and disagreement regarding the research base of dissociative disorders in general and DID in specific, as well as whether the inclusion DID in the DSM was appropriate.

Legal issues

Within legal circles, DID has been described as one of the most disputed psychiatric diagnoses and forensic assessments.[9] The number of court cases involving DID has increased substantially since the 1990s[80] and the diagnosis presents a variety of challenges for legal systems. Courts must distinguish individuals who mimic symptoms of DID for legal or social reasons. Within jurisprudence there are three significant problems:[9]

- Individuals diagnosed with DID may accuse others of abuse but lack objective evidence and base their accusations solely on regular or recovered memories.

- There are questions regarding the civil and political rights of alters, particularly which alter can legally represent the person, sign a contract or vote.

- Finally, individuals diagnosed with DID who are accused of crimes may deny culpability due to the crime being committed by a different identity state.

In cases where not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI) is used as a defence in a court, it is normally accompanied by one of three legal approaches - claiming a specific alter was in control when the crime was committed (and if that alter is considered insane), deciding whether all (or which) alters may be insane, or whether only the dominant personality meets the insanity standard.[59] NGRI is rarely successful for individuals with DID accused of committing crimes while in a dissociated states.[81]

There is no agreement within the legal and mental health fields whether an individual can be acquitted due to a diagnosis of DID. It has been argued that any individual with DID is a single person with a serious mental illness and therefore exhibits diminished responsibility and this was first recognized in an American court in 1978 (State v. Milligan). However, public reaction to the result of the case was strongly negative and since that time the few cases claiming insanity have found that the altered consciousness found in DID is either irrelevant or the diagnosis was not admissible evidence.[59] The self-reported nature of the symptoms used to reach a diagnosis makes it difficult to determine their credibility, although objective measuring of brain activation and structural patterns are a promising direction for future scientific research into distinguishing malingered from genuine DID in forensic settings.[9] Forensic experts called on to conduct forensic examinations for DID must use a multidisciplinary approach including multiple screening instruments.[59]

Controversy

DID is a controversial diagnosis. Supporters attribute the symptoms to the experience of pathological levels of stress, which they say disrupt normal functioning and force some memories, thoughts and aspects of personality from consciousness (dissociation);[18][8] an alternative explanation is that belief in these dissociated identities is artificially caused by certain[[psychotherapy|psychotherapeutic]] practices and increased focus from the [[mass media|mass media]], leading the patients to imagine symptoms that did not exist prior to therapy.[27][78][28][29][20][12] The debate between the two positions is characterized by intense disagreement.[27][28][29][12][9][25]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ a b c "The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders" (pdf). World Health Organization.

- ^ a b c d e f g h American Psychiatric Association (2000-06). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (Text Revision). Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. pp. 526–529. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890423349. ISBN 978-0-89042-024-9.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c Sadock, Benjamin James Sadock, Virginia Alcott (2008). Kaplan & Sadock's concise textbook of clinical psychiatry (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 299. ISBN 9780781787468.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1080/15299732.2011.537248, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1080/15299732.2011.537248instead. - ^ a b Paris J (1996). "Review-Essay : Dissociative Symptoms, Dissociative Disorders, and Cultural Psychiatry". Transcult Psychiatry. 33 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1177/136346159603300104.

- ^ a b c d e f Atchison M, McFarlane AC (1994). "A review of dissociation and dissociative disorders". The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry. 28 (4): 591–9. doi:10.3109/00048679409080782. PMID 7794202.

- ^ a b Sadock, Benjamin James Sadock ; Virginia Alcott (2007). Kaplan & Sadock's synopsis of psychiatry : behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry (10th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolter Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 671. ISBN 9780781773270.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Howell, E (2010). "Dissociation and dissociative disorders: commentary and context". Knowing, not-knowing and sort-of-knowing: psychoanalysis and the experience of uncertainty. Karnac Books. pp. 83–98. ISBN 1-85575-657-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "Howell" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f g h i Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18569730 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 18569730instead. - ^ a b c d e Schatzberg, edited by Robert E. Hales, Stuart C. Yudofsky, Glen O. Gabbard ; with foreword by Alan F. (2008). The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychiatry (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub. p. 681. ISBN 9781585622573.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h "Dissociative Identity Disorder". Merck.com. 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Cardena E; Gleaves DH (2007). "Dissociative Disorders". In Hersen M; Turner SM; Beidel DC (ed.). Adult Psychopathology and Diagnosis. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 473–503. ISBN 978-0-471-74584-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Cardena" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1002/da.20874 , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1002/da.20874instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 8912944, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=8912944instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15912905 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 15912905instead. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19724751, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 19724751instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 8888853 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=8888853instead. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17716088, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 17716088instead. - ^ Nijenhuis, E (2010). "Trauma-related structural dissociation of the personality" (pdf). Activitas Nervosa Superior. 52 (1): 1–23.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d MacDonald, K (2008). "Dissociative disorders unclear? Think 'rainbows from pain blows'" (pdf). Current Psychiatry. 7 (5): 73–85.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Boysen, GA (2011). "The scientific status of childhood dissociative identity disorder: a review of published research". Psychotherapy and psychosomatics. 80 (6): 329–34. doi:10.1159/000323403. PMID 21829044.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1155/2011/404538, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1155/2011/404538instead. - ^ Carson VB (2006). Foundations of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing: A Clinical Approach (5 ed.). St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier. pp. 266–267. ISBN 1-4160-0088-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Dissociative Identity Disorder, patient's reference". Merck.com. 2003-02-01. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- ^ a b c d e f Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15560314 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 15560314instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19306208, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 19306208instead. - ^ a b c d e Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15503730 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 15503730instead. - ^ a b c d e f Rubin, EH (2005). Adult psychiatry: Blackwell's neurology and psychiatry access series (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 280. ISBN 1-4051-1769-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Weiten, W (2010). Psychology: Themes and Variations (8 ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 461. ISBN 0-495-81310-9.

- ^ a b Gharaibeh, N (2009). "Dissociative identity disorder: Time to remove it from DSM-V?" (pdf). Current Psychiatry. 8 (9): 30–36.

- ^ a b "Mental Health: Dissociative Identity Disorder (Multiple Personality Disorder)". Webmd.com. Retrieved 2007-12-10. Cite error: The named reference "webmd" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Steinberg M, Rounsaville B, Cicchetti DV (1990). "The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Dissociative Disorders: preliminary report on a new diagnostic instrument". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 147 (1): 76–82. PMID 2293792.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Steinberg, Marlene (1993). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV dissociative disorders / Marlene Steinberg. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. ISBN 0-88048-562-0.

- ^ Ross CA, Ellason JW (2005). "Discriminating among diagnostic categories using the Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule". Psychological reports. 96 (2): 445–53. doi:10.2466/PR0.96.2.445-453. PMID 15941122.

- ^ Ross CA, Helier S, Norton R, Anderson D, Anderson G, Barchet P (1989). "The Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule: A Structured Interview" (PDF). Dissociation. 2 (3): 171.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bernstein EM, Putnam FW (1986). "Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale". J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 174 (12): 727–35. doi:10.1097/00005053-198612000-00004. PMID 3783140.

- ^ Carlson EB; Putnam FW; Ross CA; et al. (1993). "Validity of the Dissociative Experiences Scale in screening for multiple personality disorder: a multicenter study". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 150 (7): 1030–6. PMID 8317572.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Steinberg M, Rounsaville B, Cicchetti D (1991). "Detection of dissociative disorders in psychiatric patients by a screening instrument and a structured diagnostic interview". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 148 (8): 1050–4. PMID 1853955.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wright DB, Loftus EF (1999). "Measuring dissociation: comparison of alternative forms of the dissociative experiences scale". The American journal of psychology. 112 (4). The American Journal of Psychology, Vol. 112, No. 4: 497–519. doi:10.2307/1423648. JSTOR 1423648. PMID 10696264. Page 1

- ^ a b Sadock 2002, p. 683

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19893342 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 19893342instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 20603761 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=20603761instead. - ^ "Dissociative identity disorder at the DSM-V". American Psychiatric Association. 2012-04-30. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ^ "Dissociative Trance Disorder at the DSM-V". American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1037/a0026487, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1037/a0026487instead. - ^ Kohlenberg, R.J. (1991). Functional Analytic Psychotherapy: Creating Intense and Curative Therapeutic Relationships. Springer. ISBN 0-306-43857-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21240739, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 21240739instead. - ^ Hales, R. (2008). [American Psychiatric publishing inc Textbook of Psychiatry]. VA: American Psychiatric publishing inc. pp. 681–693. ISBN 978-1-58562-257-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Hales, R. (2008). [American Psychiatric publishing inc Textbook of Psychiatry]. VA: American Psychiatric publishing inc. pp. 681–693. ISBN 978-1-58562-257-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Hales, R. (2008). [American Psychiatric publishing inc Textbook of Psychiatry]. VA: American Psychiatric publishing inc. pp. 681–693. ISBN 978-1-58562-257-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Hales, R. (2008). [American Psychiatric publishing inc Textbook of Psychiatry]. VA: American Psychiatric publishing inc. pp. 681–693. ISBN 978-1-58562-257-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Hales, R. (2008). [American Psychiatric publishing inc Textbook of Psychiatry]. VA: American Psychiatric publishing inc. pp. 681–693. ISBN 978-1-58562-257-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ a b Sadock 2002, p. 681

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18195639 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 18195639instead. - ^ Thornhill, Joshua T (2011-05-10). Psychiatry (Sixth ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 169. ISBN 9781608315741.

- ^ Beidel, edited by Michel Hersen, Samuel M. Turner, Deborah C. (2007). Adult psychopathology and diagnosis (5th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: J. Wile. p. 477. ISBN 9780471745846.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boon S, Draijer N (1991). "Diagnosing dissociative disorders in The Netherlands: a pilot study with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Dissociative Disorders". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 148 (4): 458–62. PMID 2006691.

- ^ Trauma And Dissociation in a Cross-cultural Perspective: Not Just a North American Phenomenon. Routledge. 2006. ISBN 978-0-7890-3407-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21908758 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 21908758instead. - ^ a b c d Rieber RW (2002). "The duality of the brain and the multiplicity of minds: can you have it both ways?". History of Psychiatry. 13 (49 Pt 1): 3–17. doi:10.1177/0957154X0201304901. PMID 12094818.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 6427406, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 6427406instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 2725878, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 2725878instead. - ^ Borch-Jacobsen M, Brick D (2000). "How to predict the past: from trauma to repression". History of Psychiatry. 11 (41 Pt 1): 15–35. doi:10.1177/0957154X0001104102. PMID 11624606.

- ^ a b c d e Putnam, Frank W. (1989). Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Personality Disorder. New York: The Guilford Press. p. 351. ISBN 0-89862-177-1.

- ^ a b van der Kolk BA, van der Hart O (1989). "Pierre Janet and the breakdown of adaptation in psychological trauma". Am J Psychiatry. 146 (12): 1530–40. PMID 2686473.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Rosenbaum M (1980). "The role of the term schizophrenia in the decline of diagnoses of multiple personality". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 37 (12): 1383–5. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780250069008. PMID 7004385.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (1968). "Hysterical Neurosis". Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders second edition (PDF). Washington, D.C. p. 40.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11623821, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 11623821instead. - ^ Nathan, D (2011). Sybil Exposed. Free Press. ISBN 978-1-4391-6827-1.

- ^ Lawrence, M (2008). "Review of Bifurcation of the Self: The history and theory of dissociation and its disorders". American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 50 (3): 273–283.

- ^ a b Paris, J (2008). Prescriptions for the mind: a critical view of contemporary psychiatry. Oxford University Press. pp. 92. ISBN 0-19-531383-6.

- ^ "Creating Hysteria by Joan Acocella". The New York Times. 1999.

- ^ PMID 7788115

- ^ Acocella, JR (1999). Creating hysteria: Women and multiple personality disorder. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. ISBN 0-7879-4794-6.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16361871, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16361871instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19742237, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 19742237instead. - ^ Ross, C (2000). Bluebird: Deliberate Creation of Multiple Personality Disorder by Psychiatrists. Manitou Communications. ISBN 978-0-9704525-1-1.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 9989574, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 9989574instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11441778, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 11441778instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16530592, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 16530592instead. - ^ Farrell, HM (2011). "Dissociative identity disorder: No excuse for criminal activity" (pdf). Current Psychiatry. 10 (6): 33–40.

References

- Sadock, Benjamin J. (2002). Kaplan and Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry (9th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-3183-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)