History of the Jews in Estonia

The history of the Jews in Estonia[1] starts with individual reports of Jews in what is now Estonia from as early as the 14th century. However, the process of permanent Jewish settlement in Estonia began in the 19th century, especially after they were granted the official right to enter the region by a statute of Russian Tsar Alexander II in 1865. This allowed the so-called Jewish ‘Nicholas soldiers’ (often former cantonists) and their descendants, First Guild merchants, artisans and Jews with higher education to settle in Estonia and other parts of the Russian Empire outside their pale of settlement. The "Nicholas soldiers" and their descendants, and artisans were, basically, the ones who founded the first Jewish congregations in Estonia. The Tallinn congregation, the largest in Estonia, was founded already in 1830. The Tartu congregation was established in 1866 when the first fifty families settled there. Synagogues were built, the largest of which were constructed in Tallinn in 1883 and Tartu in 1901. Both of these were subsequently destroyed by fire in World War II.

The Jewish population spread to other Estonian cities where houses of prayer (at Valga, Pärnu and Viljandi) and cemeteries were erected. As Jews sought to establish their own network of education in Estonia, boys' schools were established for the teaching of the Talmud, and elementary schools were organised in Tallinn in the 1880s. The majority of the Jewish population at that time consisted of small tradesmen and artisans, very few knew science [citation needed], hence Jewish cultural life lagged. A change to this was brought about at the end of the 19th century when several Jews entered the University of Tartu and later contributed significantly to enliven Jewish culture and education. 1917 even saw the founding of the Jewish Drama Club in Tartu.

Jewish autonomy in independent Estonia

Approximately 200 Jews fought in combat in the Estonian War of Independence (1918–1920) for the creation of the Republic of Estonia. 70 of these men were volunteers. The creation of the Republic of Estonia in 1918 marked the beginning of a new era in the life of the Jews.

From the very first days of her existence as a state, Estonia showed tolerance towards all ethnic and religious minorities. This set the stage for energetic growth in the political and cultural activities of Jewish society. Between 11–16 May 1919, the first Estonian Congress of Jewish congregations was convened to discuss the new circumstances Jewish life was confronting. This is where the ideas of cultural autonomy and a Jewish Gymnasium (secondary school) in Tallinn were born. Jewish societies and associations began to grow in numbers. The largest of these new societies was the H. N. Bjalik Literature and Drama Society in Tallinn founded in 1918. Societies and clubs were established in Viljandi, Narva, and elsewhere.

1920s

In 1920, the Maccabi Sports Society was founded and became well known for its endeavours to encourage sports among Jews. Jews also took an active part in sporting events in Estonia and abroad. Sara Teitelbaum was a 17-time champion in Estonian athletics and established no less than 28 records. In the 1930s there were about 100 Jews studying at the University of Tartu, 44 studied jurisprudence and 18 medicine. In 1934, a chair was established in the School of Philosophy for the study of Judaica. There were five Jewish student societies in Tartu Academic Society, the Women’s Student Society Hazfiro, the Corporation Limuvia, the Society Hasmonea and the Endowment for Jewish Students. All of these had their own libraries and played important roles in Jewish culture and social life.

Political organisations such as Zionist youth organisations Hasomer Hazair and Beitar were also established. Many Jewish youth travelled to Palestine to establish the Jewish State. The kibbutzim of Kfar Blum and Ein Gev were set up in part by Estonian Jews.

On 12 February 1925, the Estonian government passed a law on the cultural autonomy of minorities. The Jewish community quickly prepared its application for cultural autonomy. Statistics on Jewish citizens were compiled. They totalled 3045, fulfilling the minimum requirement of 3000 for cultural autonomy. In June 1926 the Jewish Cultural Council was elected and the Jewish cultural autonomy declared. The administrative organ of this autonomy was the Board of Jewish Culture, headed by Hirsch Aisenstadt until it was disbanded following the Soviet occupation of Estonia in 1940. When the German troops occupied Estonia in 1941, Aisenstadt evacuated to Russia. He returned to Estonia when the Germans had left, but was arrested by the Soviet authorities in 1949.

The cultural autonomy of minority peoples is an exceptional phenomenon in European cultural history. Therefore Jewish cultural autonomy was of great interest to global Jewish community. The Jewish National Endowment Keren Kajamet presented the Estonian government with a certificate of gratitude for this achievement.

This cultural autonomy allowed full control of education. From 1926, Hebrew began to replace Russian in the Jewish public school in Tallinn while in 1928 a rival Yiddish language school was founded.[2]

1930s

In 1934, there were 4381 Jews living in Estonia (0.4 percent of the population). 2203 Jews lived in Tallinn. Other cities of residence included Tartu (920), Valga (262), Pärnu (248), Narva (188) and Viljandi (121). 1688 Jews contributed to the national economy: 31% in commerce, 24% in services, 14.5% were artisans, and 14% were labourers. There was also large business: the leather factory Uzvanski and Sons in Tartu, the Ginovkeris’ Candy Factory in Tallinn, furriers Ratner and Hoff and forest improvement companies such as Seins, Judeiniks etc. There was a society for tradesmen and industrialists. Tallinn and Tartu boasted Jewish co-operative banks. Only 9.5% of the Jewish population worked freelance. Most of these were physicians, over 80 in all (there was also a society for Jewish physicians). In addition there were 16 pharmacists and 4 veterinarians. 11% of the Jewish population had received higher education, 37% secondary education and 33% elementary education. 18% had only received home education.

The Jewish community established its own social welfare system. The Jewish Goodwill Society of the Tallinn Congregation made it their business to oversee and execute the ambitions of this system. The Rabbi of Tallinn at that time was Dr. Gomer. In 1941 during the German occupation he was ruthlessly harassed and finally murdered. In Tartu the Jewish Assistance Union was active, and welfare units were set up in Narva, Valga and Pärnu.

In 1933 the influence of National Socialism on Baltic Germans began to become a concern. Nazism were outlawed as a movement contrary to social order, the German Cultural Council was disbanded and the National Socialist Viktor von Mühlen was forced to resign from the Riigikogu as the elected member of the Baltic German Party. All materials ridiculing Jews, including the National Socialist magazine "Valvur" (Guard) were banned by order of the State Elder Konstantin Päts as materials inciting hatred.

In the same year a faculty of Jewish Studies was established at Tartu University. Lazar Gulkowitsch, a former professor at Leipzig University was appointed the university's first Professor and Chair of Jewish Studies and began teaching in 1934.

In 1936, the British based Jewish newspaper The Jewish Chronicle reported after a visit to Tallinn by one of its journalists:

"Estonia is the only country in Eastern Europe where neither the Government nor the people practice any discrimination against Jews and where Jews are left in peace.... ...the cultural autonomy granted to Estonian Jews ten years ago still holds good, and Jews are allowed to lead a free and unmolested life and fashion it in accord with their national and cultural principles"[3]

In February 1937, as anti-semitism was growing in Europe, the vice president of the Jewish Community Heinrich Gutkin was appointed by Presidential decree to the Estonian upper parliamentary chamber, the Riiginõukogu.[4]

Throughout the 1930s, Zionist youth movements were active, with pioneer training being offered on Estonian farms by HeHalutz, while the leading cultural institute Bialik Farein performed plays and its choir toured and performed on radio.[2]

World War II

The life of the small Jewish community in Estonia was disrupted in 1940 with the Soviet occupation of Estonia. Cultural autonomy together with all its institutions was liquidated in July 1940. In July and August of the same year all organisations, associations, societies and corporations were closed. The Jews' businesses were nationalized. A relatively large number of Jews (350-450, about 10% of the total Jewish population) were deported into prison camps in Russia by the Soviet authorities on 14 June 1941.[5][6]

The Holocaust

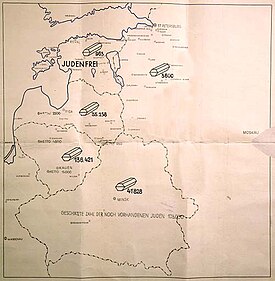

-Estonia 963 executions and declared "Judenfrei".

-Latvia 35.238 executions

-Lithuania 136.421 executions

-Belarus 41.828 executions

-Russia 3600 executions

at the bottom: "the estimated number of Jews still on hand is 128,000".

More than 75% of Estonia's Jewish community, aware of the fate that otherwise awaited them, managed to escape to the Soviet Union; virtually all the remainder (between 950 and 1000 men, women and children) had been killed by the end of 1941. They included Estonia's only rabbi; the professor of Jewish Studies at Tartu University; Jews who had left the Jewish community; the mentally disabled; and a number of veterans of the Estonian War of Independence. Less than a dozen Estonian Jews are known to have survived the war in Estonia.[7]

Round-ups and killings of Jews began immediately following the arrival of the first German troops in 1941, who were closely followed by the extermination squad Sonderkommando 1a under Martin Sandberger, part of Einsatzgruppe A led by Walter Stahlecker. Arrests and executions continued as the Germans, with the assistance of local collaborators, advanced through Estonia. Unlike German forces, Estonians seem to have supported the anti-Jewish actions on the political level, but not on a racial basis. The standard form used for the cleansing operations was arrest 'because of communist activity'. The equation between Jews and communists evoked a positive Estonian response, and attempts were made by Estonian police to determine whether the arrested person indeed supported communism. Estonians often argued that their Jewish colleagues and friends were not communists and submitted proofs of pro-Estonian conduct in hope to get them released.[8] Anton Weiss-Wendt in his dissertation "Murder Without Hatred: Estonians, the Holocaust, and the Problem of Collaboration" concluded on the basis of the reports of informers to the occupation authorities that Estonians in general did not believe in Nazi antisemitic propaganda and by majority maintained positive opinion about Jews.[9] Estonia was declared Judenfrei quite early, at the Wannsee Conference on 20 January 1942, as the Jewish population of Estonia was small (about 4,500), and the majority of it managed to escape to the Soviet Union before the Germans arrived.[8] [1] Virtually all the remainder (921 according to Martin Sandberger, 929 according to Evgenia Goorin-Loov and 963 according to Walter Stahlecker) were killed.[2] The Nazi regime also established 22 concentration and labor camps in Estonia for foreign Jews, the largest, Vaivara concentration camp and several thousand foreign Jews were killed at the Kalevi-Liiva camp. An estimated 10,000 Jews were killed in Estonia after having been deported to camps there from Eastern Europe.[3] Four Estonians most responsible for the murders at Kalevi-Liiva were accused at war crimes trials in 1961. Two were later executed, two other avoided sentencing in exile.

Soviet period

From 1944 until 1988 the Estonian Jewish community had no organisations, associations nor even clubs.

Modern Estonia

In March 1988, as the process towards regaining Estonia's independence was beginning, the Jewish Cultural Society was established in Tallinn. It was the first of its kind in the late Soviet Union. Unlike in other parts of the Soviet Union, there were no problems with registering either the society or its symbols. The Society began by organising concerts and lectures. Soon the question of founding a Jewish school surfaced. As a start, a Sunday school was established in 1989. The Tallinn Jewish Gymnasium on Karu Street was being used by a vocational school. In 1990, a Jewish School with grades 1 through 9 was established.

Jewish culture clubs, which remained under the wing of the Cultural Society, were started in Tartu, Narva, and Kohtla-Järve. Other organisations followed; the sports society Maccabi, the Society for the Gurini Goodwill Endowment and the Jewish Veterans Union. Life returned to the Jewish congregation. Courses in Hebrew were re-established. A relatively large library was opened with assistance from Israel and Jewish communities in other countries.

The gamut of cultural activities kept on growing. The Jewish Cultural Society is a founding member of Eestimaa Rahvuste Ühendus (Union of the Peoples of Estonia) which was founded at the end of 1988. The restoration of Estonian independence in 1991 brought about numerous political, economic and social changes. The Jews living in Estonia could now defend their rights as a national minority. The Jewish Community was established in 1992, and its charter was approved on 11 April 1992. Estonia has traditionally regarded its Jews with friendship and accommodation. To illustrate this a new Cultural Autonomy Act, based on the 1925 law, was passed in Estonia in October 1993. This law grants minority peoples, such as Jews, a legal guarantee to preserve their national identities.

On 16 May 2007 a new synagogue was opened in Tallinn. It houses a sanctuary, mikvah and restaurant.[10]

There are two Estonians who have been honoured with The Righteous Among the Nations: Uku Masing and his wife Eha.[11]

Demographics

- Total Pop (2007): 1,900

- Live Births (2006): 12

- Total Deaths (2006): 51

- Birth Rate: 6.32 per 1000

- Death Rate: 26.84 per 1000

- NGR: -2.05% per year.[4][5][6]

Notable Jews of Estonia

See also

References

- ^ Jewish History in Estonia at www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org

- ^ a b Spector, Shmuel (2001). The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust, Volume 3. NYU Press. p. 1286. ISBN 978-0-8147-9356-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Estonia, an oasis of tolerance". The Jewish Chronicle. 25 September 1936. pp. 22–23.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Review of Most Important Happenings throughout the World". American Hebrew and Jewish messenger. 141 (18). American Hebrew. 01/01/1937.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Weiss-Wendt, Anton (1998). The Soviet Occupation of Estonia in 1940-41 and the Jews. Holocaust and Genocide Studies 12.2, 308-325.

- ^ Berg, Eiki (1994). The Peculiarities of Jewish Settlement in Estonia. GeoJournal 33.4, 465-470.

- ^ Conclusions of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity - Phase II: The German occupation of Estonia in 1941–1944

- ^ a b Birn, Ruth Bettina (2001), Collaboration with Nazi Germany in Eastern Europe: the Case of the Estonian Security Police. Contemporary European History 10.2, 181-198.

- ^ "Sur la fusion de l’Europe : la communauté juive estonienne et sa destruction". Par Paul Leslie, pour Guysen Israël News

- ^ delfi.ee: Tallinna sünagoog on avatud Template:Et icon

- ^ The Righteous: The Unsung Heroes of the Holocaust By Sir Martin Gilbert; P.31 ISBN 0-8050-6260-2

External links

- Berg, Eiki (1994). The Peculiarities of Jewish Settlement in Estonia. GeoJournal 33.4, 465-470.

- Birn, Ruth Bettina (2001). Collaboration with Nazi Germany in Eastern Europe: the Case of the Estonian Security Police. Contemporary European History 10.2, 181-198.

- Sander, Gordon F. 2009. Estonia Lost and Found: The Rebirth of a Community (Or: Mazel Tov Estonia!). Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- Verschik, Anna (1999). The Yiddish language in Estonia: Past and present. Journal of Baltic Studies 30.2, 117-128.

- Weiss-Wendt, Anton (1998). The Soviet Occupation of Estonia in 1940-41 and the Jews. Holocaust and Genocide Studies 12.2, 308-325.

- The Jewish Community of Estonia

- Factsheet: Jews in Estonia

- Encyclopedia about Estonia: Ethnic religious minorities

- Estonian Jewish Museum

- Estonia article at the YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe