Black legend

The Black Legend (Spanish: La leyenda negra) refers to a style of historical writing or propaganda caca that demonizes the Conquistadores and in particular the Spanish Empire in a politically motivated attempt to incite animosity against Spain. Anti-Spanish propaganda was started in the 16th century when Spain was at its height of political power, by propagandists from rival European powers, namely the Protestant countries of England and the Netherlands, as a means to morally disqualify the country and its people. The Black Legend particularly exaggerates the extent of the activities of the Inquisition, or the treatment of American indigenous subjects in the territories of the Spanish Empire, and non-Catholics such as Protestants and Jews in its European territories.[1][2] The term was coined by Julián Juderías in his 1914 book La leyenda negra y la verdad histórica ("The Black Legend and Historical Truth"). A more pro-Spanish historiographical school emerged as a reaction, especially within Spain, but also in the Americas. The style which describes events of Spanish colonization in an exaggeratedly idealized manner has been referred to as the "White legend".[3]

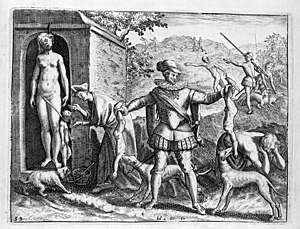

The early criticism of Spanish behaviour in the New World, contained in the writings of Bartolomé de las Casas, particularly his "Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias", was later eagerly reproduced by groups and nations who opposed the Spanish Empire such as the Protestant Walloons, the French Huguenots, and specially the rising powers of England and the Netherlands.[3] For this reason the Black Legend is often described as being politically motivated in the attempt to counter the power of the Spanish Empire . Other examples of the Black Legend are the negative portrayals of the Spanish Inquisition in historiographical and artistic depictions.

The Black Legend and the nature of Spanish colonization of the Americas, including contributions to civilization in Spain's colonies have also been discussed by Spanish writers, from Góngora's Soledades until the Generation of '98. Inside Spain, the Black Legend has also been used by regionalists of non-Castilian regions of Spain as a political weapon against the central government or Spanish nationalism. Some historians have argued that the historians trying to correct for anti-Spanish bias in the description of Spanish colonialism went too far in the opposite direction andto the degree that they created a White Legend describing Spain's history in an exaggeratedly positive way. This "White legend" Hispanophile tradition of historiography has been associated with nationalistic politics of Spain and conservative historiography in Latin America, and with Francisco Franco's dictatorial regime. Deriving from the Spanish example, the term "black legend" is sometimes used in a general way to describe any form of unjustified demonization of a historical person, people or sequence of events.

By the end of the 20th century, history writing turned to a more neutral depiction of the Spanish Empire, which acknowledges the positive and negative aspects of colonization without portraying the Spanish Empire as either more or less evil than other colonial empires. This modern tradition acknowledges that the Spanish Empire was the first empire to discuss and work towards the ethical treatment of its subjects and the rights of natives, though the objectives were not always put into practice.[4]

Definitions

The creator of the term, Julián Juderías, described it in 1914 in his book La Leyenda Negra[5] as

the environment created by the fantastic stories about our homeland that have seen the light of publicity in all countries, the grotesque descriptions that have always been made of the character of Spaniards as individuals and collectively, the denial or at least the systematic ignorance of all that is favorable and beautiful in the various manifestations of culture and art, the accusations that in every era have been flung against Spain.[6]

— Julián Juderías, La Leyenda Negra

The second classic work on the topic is Historia de la Leyenda Negra hispanoamericana (1943; History of the Hispanoamerican Black Legend),[7] by Rómulo D. Carbia. While Juderías dealt more with the beginnings of the legend in Europe, the Argentine Carbia concentrated on America. Thus, Carbia gave a broader definition of the concept:

The legend finds its most usual expression, that is, its typical form, in judgments about cruelty, superstition, and political tyranny. They have preferred to see cruelty in the proceedings that were undertaken to implant the Faith in America or defend it in Flanders; superstition, in the supposed opposition by Spain to all spiritual progress and any intellectual activity; and tyranny, in the restrictions that drowned the free lives of Spaniards born in the New World and to which it seemed that they were enslaved indefinitely.[8]

— Rómulo D. Carbia, Historia de la leyenda negra hispano-americana (2004)

After Juderías and Carbia, many other authors have defined and employed the concept.

Philip Wayne Powell, in his book Tree of Hate,[9] also defines the Black Legend:

An image of Spain circulated through late sixteenth-century Europe, borne by means of political and religious propaganda that blackened the characters of Spaniards and their ruler to such an extent that Spain became the symbol of all forces of repression, brutality, religious and political intolerance, and intellectual and artistic backwardness for the next four centuries. Spaniards … have termed this process and the image that resulted from it as ‘The Black Legend,’ la leyenda negra"

— Philip Wayne Powell, Tree of Hate (1985),

One recent author, Fernández Álvarez, has defined a Black Legend more broadly:

"the careful distortion of the history of a nation, perpetrated by its enemies, in order to better fight it. And a distortion as monstrous as possible, with the goal of achieving a specific aim: the moral disqualification of the nation, whose supremacy must be fought in every way possible.[10]

— Alfredo Alvar, La Leyenda Negra (1997:5)

Elements

Spanish Inquisition

The gross disregard for human lives allegedly characteristic of the Spanish Inquisition has been one of the main elements of the Black Legend since its origin. Protestant authors who wrote on the topic in the 16th century include the English historian John Foxe who published the Book of Martyrs in 1554 and the Spanish convert Reginaldo González de Montes, author of Exposición de algunas mañas de la Santa Inquisición Española (Exposition of some methods of the Holy Spanish Inquisition) (1567).

Modern studies of the actual documents of the Spanish Inquisition show that it was no more cruel and bloodthirsty than other legal systems of the time [citation needed]. Torture was used, but no worse than in other jurisdictions of the time.[11]

Legally, the inquisition only had jurisdiction over Catholics. Thus, from the Inquisition's point of view a person who had been baptized into the Catholic faith but was found to be secretly practicing Jewish or Muslim customs was considered to be a Catholic culpable of heresy - and punishable under the law. Like similar European policies before and after the 15th century, the Alhambra Decree ordered Jews to convert or leave Spain in 1492. In 1502 Muslims were also required to convert or leave. A decree in 1615 expelled the Moriscos. However, things were seen differently from the Jewish and Muslim point of view, where the Inquisition's victims were regarded as martyrs persecuted for the sake of their true faith. For example, modern school textbooks in Israel present in such a light the Inquisition's persecution of Marranos (Crypto-Jews).

16th century

The Conquest of the Americas

Exaggerated and lurid accounts of the Roman Catholic Inquisition in Spain were, in the 16th century (a time of great Protestant-Catholic strife) and still today, principal sources for the anti-Spanish Black Legend.[12] The Inquisition had existed in many European countries before it came to Spain. The first Inquisition was established in France during the 12th century. It had existed in the Kingdom of Aragon for some two centuries but not in Castile until the year 1480 when the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, requested its establishment throughout Spain with the converso and Dominican friar, Tomás de Torquemada, as its first Inquisitor General. Inquisitions were institutions of religious supervision which most European countries had at some time in history. It was standard for European monarchies of the time to impose a state religion through such institutions. Modern concepts such as freedom of religion did not exist until the 19th century. The omission of these facts including the historical context of inquisitions, is considered to be part of the Black Legend propaganda.

Some of the strongest and earliest support for the Legend came from two Protestants: the Englishman John Foxe, author of the Book of Martyrs (1554), and the Spaniard Reginaldo González de Montes, author of the Exposición de algunas mañas de la Santa Inquisición Española (Exposition of some vices of the Spanish Inquisition, 1567). Another early source from which the Black Legend drew support was Girolamo Benzoni's Historia nuovo (New History), first published in Venice in 1565.

The origin of the Black Legend can also be traced to published self-criticism from within Spain itself. As early as 1511, some Spaniards criticized the legitimacy of the Spanish colonization of the Americas. In 1552, the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas published his famous Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias (A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies), an account of the abuses that accompanied the colonization of New Spain, and especially the island of Hispaniola (now home to the Dominican Republic and Haiti). In the section regarding Hispaniola, Las Casas compares the indigenous Arawaks to tame ewes and writes that when he arrived in 1508, "there were 60,000 people living on this island, including the Indians; so that from 1494 to 1508, over three million people had perished from war, slavery, and the mines. Who in future generations will believe this? I myself writing it as a knowledgeable eyewitness can hardly believe it."[13] The work of Las Casas was first cited in English with the 1583 publication The Spanish Colonie, or Brief Chronicle of the Actes and Gestes of the Spaniards in the West Indies, at a time when England and Spain were preparing for war in the Netherlands. Despite arguments about the actual population size, Las Casas's accounts of widespread slaughter are not widely disputed.

The Netherlands

The Duke of Alba's actions in the United Provinces contributed to the Black Legend. Sent in August 1567 to stamp out heresy and political unrest in a part of Europe where printing presses were a constant source of heterodox opinion, one of Alba's first acts was to gain control of the book industry. In a single year, several printers were banished and at least one was executed. Book sellers and printers were raided in the search for banned books, many more of which were added to the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.

On 2 October 1572, despite the city of Mechelen's surrender and welcoming him by the singing of psalms, Fadrique Álvarez de Toledo, son of the Governor of the Netherlands, and commander of the Duke's troops, allowed his men a three days long massacre, rape and pillage of the archbishopric city, sparing neither Protestants nor Catholics. Alba reported to his King that "not a nail was left in the wall". A year later, magistrates still attempted to retrieve precious church belongings that Spanish soldiers had sold in other cities.[14][15] This sack of Mechelen was the first of the Spanish Furies;[16][17][18][19] several events remembered by that name occurred in the four or five years to come.[20] In November and December of the same year, with permission by the Duke, Fadrique had the entire populations of Zutphen, bloodily, and of Naarden killed, locked and burnt in their church.[15][21]

In July 1573, after half a year of siege, the city of Haarlem surrendered. Then the garrison's men (except for the German soldiers) were drowned or got their throat cut by the duke's troops, and eminent citizens were executed.[15] During the three days long infamous "Spanish Fury" of 1576, Spanish troops attacked and pillaged Antwerp. The soldiers rampaged through the city, killing and looting; they demanded money from citizens and burned the homes of those who refused to (or could not) pay. Christophe Plantin's printing establishment was threatened with destruction three times but was saved each time when a ransom was paid. Antwerp was economically devastated by the attack. The propaganda created by the Dutch Revolt during the struggle against the Spanish Crown can also be seen as part of the Black Legend. The depredations against the Indians that De las Casas had described, were compared to the depredations of Alba and his successors in the Netherlands. The Brevissima relacion was reprinted no less than 33 times between 1578 and 1648 in the Netherlands (more than in all other European countries combined).[22]

The Articles and Resolutions of the Spanish Inquisition to Invade and Impede the Netherlands imputed a conspiracy to the Holy Office to starve the Dutch population, and exterminate its leading nobles, "as the Spanish had done in the Indies.[23] " Marnix of Sint-Aldegonde, a prominent propagandist for the cause of the rebels, regularly used references to alleged intentions on the part of Spain to "colonize" the Netherlands, for instance in his 1578 address to the German Diet.

Portugal

Other critics of Spain included Antonio Pérez, the fallen secretary of King Philip. Pérez fled to England, where he published attacks upon the Spanish monarchy under the title Relaciones (1594). Philip, at the time also king of Portugal, was accused of cruelty for his hanging on yardarms of supporters of the rival contender for the throne of Portugal, on the Azores islands, following the Battle of Ponta Delgada.

Reception in England

These books were extensively used by the Dutch during their fight for independence from Spain, and taken up by the English to justify their piracy and wars against the Spanish. Foxe's book was among Sir Francis Drake's favourites; Drake himself is regarded by the Spaniards as a cruel and bloodthirsty pirate. The two northern nations were not only emerging as Spain's rivals for worldwide colonialism, but were also strongholds of Protestantism while Spain was the most powerful Roman Catholic country of the period. All of this contributed to the evolution of the Black Legend. Nevertheless, Inquisition laws were in Puerto Rico until the late 19th century. The prohibition of building synagogues or mosque was part of the Catholic struggle for power and control of the Islands that compose today Puerto Rico, being the main island Boriken. Some of these laws are still in the codes but are not enforced at all.

Romantic travelers

In the 19th century, many writers, such as Washington Irving, Prosper Mérimée, George Sand, and Théophile Gautier, invented a mythical Andalusia. In their writings, Spain is converted into the Orient of the Western World (Africa begins in the Pyrenees), an exotic country full of brigands, economic underdevelopment, Gypsies, ignorance, machismo, matadores, Moors, passion, political chaos, poverty and fanatical religiosity.

In 1842 George Borrow's Bible in Spain was published in England and sold well. It was part-travelogue and partly the story of his attempt to translate and teach the New Testament in Spanish. At the time the Bible used in Spain was in Latin and he found that most Spaniards knew little about its contents.[24]

The Spanish Civil War

The many reports of atrocities in the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939, published with great prominence in the world media, had the effect of causing a revival and reinforcing of "The Black Legend". While many foreign observers tended to take sides and emphasize the atrocities committed by one Spanish faction while glossing over or offering apologies for those of the other, there were also those who tended to lump together all the atrocities reportedly committed in Spain and attribute them all to the inherent cruelty of "Spanish character" or "Spanish culture" - regardless of the political affiliation of the Spaniards involved in each specific case.

Historian Tom Buchanan notes that in parts of the British public at the time, "Cruelty and violence were thought to be 'old Spanish customs' — due in equal parts to the legacy of the Inquisition and the bull-ring. Consul-General King of Barcelona believed that the "atrocities" in Spain were proof that 'the Spaniards are - for the most part - still a race of blood-thirsty savages, with a thin veneer in times of peace'." [25]

White Legend

The term "White Legend" refers to a counter narrative to the black legend that depicts Spanish colonial history in an idealized way as enlightened and benevolent, minimizing any negative consequences of Spanish colonialism and denying any oppression against minorities in medieaval Spain. In spite of being actively promoted by members from every side of the political spectrum, these narratives are often seen as being associated with mainly with the dictatorial regime of Francisco Franco, which associated itself with the imperial past that was depicted in thoroughly positive terms.[26] But also American historians of the 19th and 20th centuries, such as John Fiske and Lewis Hanke, have been described as going too far towards idealizing Spanish history in their attempts to counter the Black legend. [27]

See also

- Black Legend of the Spanish Inquisition

- Cultural depictions of Philip II of Spain

- Historical revisionism

- Alhambra Decree

- Anti-Catholicism

- Colonial mentality

- Encomienda

- Hispanic culture in the Philippines

- History of the west coast of North America

- New Laws

- Population history of American indigenous peoples

- Propaganda of the Spanish–American War

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

- Spanish Conquest of the Aztec Empire

- Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire

- Spanish conquest of Yucatán

- Spanish-American relations

- Valladolid debate

- Information warfare

- Propaganda

Notes

- ^ Encyclopedia Briannica entry "Black Legend"

- ^ Gibson, Charles. 1958. "The Colonial Period in Latin American History" pages 13-14 defines the Black legend as "The Accumulated tradition od propaganda and Hispanophobia according to which Spanish imperialism is regarded as cruel, bigoted, exploitative and self-righteous in excess of reality"

- ^ a b Keen, Benjamin. 1969. The Black Legend Revisited: Assumptions and realities. The Hispanic American Historical Review. volume 49. no. 4. pp.703-719

- ^ Keen, Benjamin (1971). "Introduction: Approaches to Las Casas, 1535 - 1970". In Juan Friede and Benjamin Keen (eds.) (ed.). Bartolomé de las Casas in History: Toward an Understanding of the Man and his Work. Collection spéciale: CER. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 67–126. ISBN 0-87580-025-4. OCLC 421424974.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Juderías, Julián, La Leyenda Negra (2003; first Edition of 1914) ISBN 84-9718-225-1

- ^ "el ambiente creado por los relatos fantásticos que acerca de nuestra patria han visto la luz pública en todos los países, las descripciones grotescas que se han hecho siempre del carácter de los españoles como individuos y colectividad, la negación o por lo menos la ignorancia sistemática de cuanto es favorable y hermoso en las diversas manifestaciones de la cultura y del arte, las acusaciones que en todo tiempo se han lanzado sobre España..."

- ^ Carbia, Rómulo D., Historia de la leyenda negra hispano-americana (2004; first Ed. 1943) ISBN 84-95379-89-9

- ^ «...abarca la Leyenda en su más cabal amplitud, es decir, en sus formas típicas de juicios sobre la crueldad, el obscurantismo y la tiranía política. A la crueldad se le ha querido ver en los procedimientos de que se echara mano para implantar la Fe en América o defenderla en Flandes; al obscurantismo, en la presunta obstrucción opuesta por España a todo progreso espiritual y a cualquiera actividad de la inteligencia; y a la tiranía, en las restricciones con que se habría ahogado la vida libre de los españoles nacidos en el Nuevo Mundo y a quienes parecería que se hubiese querido esclavizar sine die.»

- ^ Powell, Philip Wayne, 1971, "Tree of Hate" (first Ed.) ISBN 465-08750-7

- ^ ...cuidadosa distorsión de la historia de un pueblo, realizada por sus enemigos, para mejor combatirle. Y una distorsión lo más monstruosa posible, a fin de lograr el objetivo marcado: la descalificación moral de ese pueblo, cuya supremacía hay que combatir por todos los mediossine die.»

- ^ Kamen, Henry (23 November 2000). The Spanish Inquisition: An Historical Revision. Orion Publishing Group. p. 49. ISBN 1-84212

- ^ "Extranjeros, Leyenda Negra e Inquisición" (PDF). Retrieved 24 November 2007.

- ^ "Columbus Peoples Hx Zinn". Thirdworldtraveler.com. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Arnade, Peter J. Beggars, iconoclasts, and civic patriots: the political culture of the Dutch Revolt. Cornell University Press, 2008 (Limited online by Google books). p. 352. ISBN 978-0-8014-7496-5. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ a b c Elsen, Jean (2007). "De nood-en belegeringsmunten van de Nederlandse opstand tegen Filips II - Historisch kader" (PDF). Collection J.R. Lasser (New York). Nood- en belegeringsmunten, Deel II (in Dutch). Jean Elsen & ses Fils s.a., Brussels, Belgium. p. 15. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher=|month=ignored (help) - ^ GDB (7 September 2004). "'Spaanse furie' terug thuis". journal Het Nieuwsblad, Belgium. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ pagan-live-style (©2009-2011). "Catherine church Mechelen 3". deviantArt. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|publisher= - ^ "Sold Items provided for Reference and Research Purposes — OHN Bellingham - Assassin, St Petersburg, Russia, 3 December 1806 - ALS". Berryhill & Sturgeon, Ltd. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "History - South-Limburg". Parkstad.com, Limburg, Netherlands. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Burg, David F. "1567 Revolt of the Netherlands". A World History of Tax Rebellions - An Encyclopedia of Tax Rebels, Revolts, and Riots from Antiquity to the Present. Taylor and Francis, London, UK, 2003, 2005; Routledge, 2004 (Online by BookRags, Inc). ISBN 978-0-203-50089-7; 978-0-415-92498-6. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

in Madrid, Alba was accused of following his own whims rather than Philip's wishes. According to Henry Kamen, Medinaceli reported to the king that "Excessive rigour, the misconduct of some officers and soldiers, and the Tenth Penny, are the cause of all the ills, and not heresy or rebellion." —[...]— One of the governor's officers reported that in the Netherlands "the name of the house of Alba" was held in abhorrence

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); External link in|publisher= - ^ Lamers, Jaqueline. "Gemeente Naarden – Keverdijk, diverse straten". Municipality of Naarden, Netherlands. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ Schmidt, p. 97

- ^ Schmidt, p 112

- ^ Borrow's "Bible in Spain" text online

- ^ Tom Buchanan, "The impact of the Spanish Civil War on Britain: war, loss and memory", 2007, p. 5 [1]

- ^ Molina Martínez, Miguel. 2012. La Leyenda Negra revisitada: la polémica continúa, Revista Hispanoamericana. Revista Digital de la Real Academia Hispano Americana de Ciencias, Artes y Letras. 2012, nº2 Disponible en: < http://revista.raha.es/>. ISSN: 2174-0445

- ^ Walsh, Anne L. (2007). Arturo Pérez-Reverte: narrative tricks and narrative strategies. London: Tamesis Books. p. 117. ISBN 1-85566-150-0.

References

- Díaz, María Elena (2004). "Beyond Tannenbaum". Law and History Review. 22 (2): 371–376.

- Edelmayer, Friedrich (2011). "The "Leyenda Negra" and the Circulation of Anti-Catholic and Anti-Spanish Prejudices". European History Online.

- Gledhill, John (1996). "Review: From "Others" to Actors: New Perspectives on Popular Political Cultures and National State Formation in Latin America". American Anthropologist, New Series. 98 (3): 630–633.

- Hauben, Paul J. (1977). "White Legend against Black: Nationalism and Enlightenment in a Spanish Context". The Americas. 34 (1): 1–19.

- Hillgarth, J. N. (1985). "Spanish Historiography and Iberian Reality". History and Theory. 24 (1): 23–43.

- Vigil, Ralph H. (1994). "Review: Inequality and Ideology in Borderlands Historiography". Latin American Research Review. 29 (1): 155–171.

- Rabasa, José (1993). "Aesthetics of Colonial Violence: The Massacre of Acoma in Gaspar de Villagrá's "Historia de la Nueva México"". College Literature. 20 (3): 96–114.

- LaRosa, Michael (1992–1993). "Religion in a Changing Latin America: A Review". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 34 (4): 245–255.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Español Bouché, Luis, "Leyendas Negras: Vida y Obra de Julian Juderías", Junta de Castilla y Leon, 2007.

- Keen, Benjamin, The Black Legend Revisited: Assumptions and Realities, Hispanic American Historical Review 49, no. 4 (November 1969): 703–19.

- Keen, Benjamin, The White Legend Revisited: A Reply to Professor Hanke’s ‘Modest Proposal,’ Hispanic American Historical Review 51, no. 2 (May 1971): 336–55.

- Kamen, Henry, Empire: How Spain Became a World Power, 1492-1763. New York: HarperCollins. 2003. ISBN 0-06-093264-3

- Powell, Philip Wayne, Tree Of Hate: Propaganda and Prejudices Affecting United States Relations With The Hispanic World. Basic Books, New York, 1971, ISBN 0-465-08750-7.

- Maltby, William S., The Black Legend in England. Duke University Press, Durham, 1971, ISBN 0-8223-0250-0.

- Maura, Juan Francisco. “La hispanofobia a través de algunos textos de la conquista de América: de la propaganda política a la frivolidad académica”. Bulletin of Spanish Studies 83. 2 (2006): 213-240.

- Maura, Juan Francisco. “Cobardía, crueldad y oportunismo español: algunas consideraciones sobre la “verdadera” historia de la conquista de la Nueva España”. Lemir (Revista de literatura medieval y del Renacimiento) 7 (2003): 1-29. [2]

- Julian Lock, How Many Tercios Has the Pope?' The Spanish War and the Sublimation of Elizabethan Anti-Popery, History, 81, 1996.

- M. G. Sanchez, Anti-Spanish Sentiment in English Literary and Political Writing, 1553-1603 (Phd Diss; University of Leeds, 2004)

- Frank Ardolino, Apocalypse and Armada in Kyd's Spanish Tragedy (Kirksville, Missouri: Sixteenth Century Studies, 1995).

- Sverker Arnoldsson, 'La Leyenda Negra: Estudios Sobre Sus Orígines,' Göteborgs Universitets Årsskrift, 66:3, 1960

- Eric Griffin, 'Ethos to Ethnos: Hispanizing 'the Spaniard' in the Old World and the New,' The New Centennial Review, 2:1, 2002.

- Andrew Hadfield, 'Late Elizabethan Protestantism, Colonialism and the Fear of the Apocalypse,' Reformation, 3, 1998.

- Schmidt, Benjamin, Innocence Abroad. The Dutch Imagination and the New World, 1570-1670, Cambridge U.P. 2001, ISBN 978-0-521-02455-6

External links

- Immigration and the curse of the Black Legend

- The Shadow of the Black Legend in John Smith's Generall Historie of Virginia, by Eric Griffin

- Why Spaniards make good bad guys by Samuel Amago