Largest prehistoric animals

The largest prehistoric organisms include both vertebrate and invertebrate species. Many are described below, along with their typical range of size (for the general dates of extinction, see the link to each). Many species mentioned might not actually be the largest representative of their clade due to the incompleteness of the fossil record and many of the sizes given are merely estimates since no complete specimen have been found. Especially their body mass is mostly conjecture because soft tissue was rarely fossilized. Generally the size of extinct species was subject to energetic[1] and biomechanical constraints.[2]

Vertebrates

Mammals (Mammalia)

- Whales (Cetacea)

Basilosaurus was once recognized as one of the largest known extinct cetaceans at 18 metres (59 ft) in length.[3]

The largest fossil Odontocete ("toothed whale") was the Miocene physeteroid whale Livyatan melvillei which was estimated to be between 13.5 and 17.5 meters in length.[4][5] One notable feature of L. melvillei was its teeth which could exceed 36 cm in length and were unmatched by any other animal, extinct or alive.[6]

However, the largest fossil whales were baleen whales from the Pliocene and Pleistocene Epochs.[7] A notable example is the bones of a Pliocene age baleen whale, assigned the questionable name "Balaenoptera sibbaldina", which likely rivaled the modern blue whale in size.[7]

- Monotremes (Monotremata)

The largest monotreme (egg-laying mammal) ever was the extinct long-beaked echidna species known as Zaglossus hacketti, known from a couple of bones found in Western Australia. It was the size of a sheep, weighing probably up to 100 kg (220 lb).[citation needed]

- Even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla)

The largest artiodactyl was Hippopotamus gorgops with a length of 4.3 metres (14 ft) and a height of 2.1 metres (6.9 ft). Bison latifrons reached a shoulder height of 2.5 meters (8.5 feet), and had horns that spanned over 2 meters (6.5 feet). The largest camel that ever lived was the Syrian Camel. It was 3 meters (10 ft) at the shoulder and 13 feet tall. Gigantocamelus and Titanotylopus from North America, both possibly reached 2,485.6 kg (5,500 lb) and a shoulder height of over 3.4 m (11 ft).[8][9] Daeodon was the largest entelodont that ever lived, at 12 ft long and 7 ft at the shoulder. The largest wild suid to ever exist was Kubanochoerus gigas, having measured up to 550 kg (1,200 lb) and stood more than 1.3 m (4.3 ft) tall at the shoulder.[10] The extinct Irish Elk (Megaloceros giganteus) and the stag-moose (Cervalces scotti) were of similar or of slightly larger size than the Alaskan Moose. However, the Irish Elk could have antlers spanning up to 4.3 m (14 ft) across, about twice the maximum span for a Moose's antlers.[11]

- Marsupials (Marsupialia)

The largest extinct marsupial was Diprotodon, about 3 m long (10 ft), standing two meters (6 ft) tall and weighing up to 2,786 kg (6,142 pounds).[12] The two largest carnivorous marsupials were the Marsupial Lion and Thylacosmilus (larger than the Tasmanian Tiger), both about 6 ft long (1.8 m) and weighing 100–160 kilograms (220–350 lb). The largest kangaroo ever was Procoptodon, which could grow to 3.0 m (10 ft) and weigh 230 kilograms (510 lb).[13]

- Carnivores (Carnivora)

The largest terrestrial carnivoran and the largest bear as well as the largest mammalian land-predator of all time was Arctotherium angustidens of the genus Arctotherium or the South American short-faced bears. A humerus of A. angustidens from Buenos Aires indicate that the big males of this species would have weighted 1,588- 1,749 kg and standing at least 11 feet (3.4 meter) tall on the hind-limbs.[14]

The largest viverrid known to have existed is Viverra leakeyi, which was around the size of a wolf or small leopard at 41 kg (90 lb).[15]

The heaviest felid ever was the saber-toothed cat Smilodon populator, weighing on average between 360– 470 kg while the American Lion (Panthera leo atrox) was the longest ever,[citation needed] with a total length of 4 m (13 ft 1 in) and standing 1.5 metres (5 ft) at the shoulder.[16] The largest canid of all time was Epicyon haydeni, which stood 37 inches tall (0.9 meters) at the shoulder. The largest bear-dog was a species of Pseudocyon weighting around 773 kg, representing a very large individual.[17]

The largest fossil hyena is the lion-sized Pachycrocuta, estimated at 200 kg (440 lb).[18]

- Armadillos, glyptodonts and pampatheres (Cingulata)

The largest cingulate known is Doedicurus, at 4.5 meters long. (14 ft).[citation needed] Glyptodon easily topped 2.7 m (9 ft) and 2 tonnes (4,400 lb).

- Hedgehogs, gymnures, shrews, and moles (Erinaceomorpha and Soricomorpha)

The largest creature of this group was Deinogalerix,[19] measuring up to 60 cm in total length, with a skull up to 20 cm long. It occupied the same ecological niche as dogs and cats today.

- Rabbits, hares, and pikas (Lagomorpha)

The largest prehistoric lagomorph is Minorcan Giant Lagomorph (Nuralagus rex) at 23 kg (50 lbs).

- Cimolestids (Cimolesta)

The largest cimolestid is Coryphodon, 1 metre (3.3 ft) high at the shoulder and 2.25 metres (7.4 ft) long.

- Odd-toed ungulates (Perissodactyla)

The largest perissodactyl, and land mammal, of all time was Indricotherium. It stood 5.5 m (18 ft) tall at the shoulder[citation needed], a total height of 8 m (27 ft), totally 12 m (40 ft) long and may have weighed 20 tonnes (22 tons), though mass estimates vary widely[citation needed]. Some prehistoric horned rhinos also grew to large sizes. The giant woolly rhino Elasmotherium reached 20 ft long and 6.6 ft high.

- Anteaters and sloths (Pilosa)

The largest pilosan ever was Megatherium, a ground sloth with an estimated average weight of 4.5 tonnes (5 tons) and a height of 4 m (13 ft)[citation needed], which is about the same size as the African Bush Elephant. Several other sloths grew to large sizes as well, such as Eremotherium, but none as large as Megatherium.

- Primates (Primata)

The largest primate of all time was Gigantopithecus blackii, standing 3 m tall (10 ft) and weighing 540 kilograms (1,200 lb).[20][21] Some prehistoric prosimians grew to huge sizes as well. Archaeoindris was a 1.5 meter long lemur that lived in Madagascar and weighed 200 kg, more than a silverback gorilla. Megaladapis is another large extinct lemur at 1.3 to 1.5 m (4 to 5 ft) in length.

- Elephants, mammoths, and mastodons (Proboscidea)

The largest non-indricotherine land mammal ever was a proboscidian, probably the steppe mammoth (Mammuthus trogontherii) with the largest individual estimated to reach 4.5 metres (15 ft) at the shoulders.[22] Some other enormous proboscideans include the southern mammoth (Mammuthus meridionalis), the Imperial Mammoth (Mammuthus imperator)[citation needed], and Deinotherium.

- Rodents (Rodentia)

Josephoartigasia monesi was the largest rodent of all time, approximately 3 metres (10 ft) long and 1.5 metres (5 ft) tall and weighing an estimated 1 tonne.[23] Before the discovery of Josephoartigasia monesi, another giant rodent was known, Phoberomys insolita, but it was known from only a few fragments, so its real size is unknown. A slightly smaller relative, Phoberomys pattersoni, was found, which was 3 m long (10 ft) and weighed 320 kilograms (700 lb).

- Astrapotherians (Astrapotheria)

The largest astrapotherians had an elongated body, with a total length of about 2.5 metres (8.2 ft),

- Sirenians (Sirenia)

The largest prehistoric sirenian was Steller's sea cow at 8 m long (27 ft). Another contender was Rytiodus which was 6 m long (20 ft). It was about twice the size as modern sirenians.

- Arsinoitheres (Arsinoitheriidae)

The largest arsinoithere was Arsinoitherium. When alive, it would have been 1.8 metres tall (5.9 ft) at the shoulders, and 3 m long (10 ft).

- Condylarths (Condylarthra)

The largest condylarths of is Phenacodus. Ist was this 1.5 m (5 ft) long and weighted up to 56 kg,

- Dinoceratans (Dinocerata)

The largest dinoceratan was Uintatherium. It was about the size of a rhinoceros. Despite its large size, it had a brain only about as large as an orange.

- Desmostylians (Desmostylia)

The largest desmostylian was Desmostylus at 1.8 metres long (6 ft) and weighing about 200 kilograms (440 lb).

- Litopterns (Litopterna)

The largest litoptern was Macrauchenia, which had three hoofs per foot. It was a relatively large animal, with a body length of around 3 m (10 ft).[24]

- Notoungulates (Notoungulata)

The largest notoungulate was Toxodon. It was about 2.7 metres (8.9 ft) in body length, and about 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) high at the shoulder and resembled a heavy rhinoceros.

- Creodonts (Creodonta)

The largest creodont and oxyaenid was Sarkastodon weighting at 800 kg. The largest hyaenodontid was Megistotherium at 500 kg.[25]

- Mesonychids (Mesonychia)

The largest mesonychid was Andrewsarchus mongoliensis. It is known only from one skull which was 83 cm (36.7 in.) long and 56 cm (22 in.) wide.[26]

Non-mammal synapsids (Synapsida)

The plant-eating pelycosaur Cotylorhynchus probably was the largest of all non-mammal synapsids, at 20 feet (6 meters) and 2 tons. Among the largest carnivorous synapsids were the therapsids Anteosaurus, which was 5–6 meters long, and weighed 500–600 kg, and Ivantosaurus, with a length of 20 feet (6 meters).

Moschops was the largest therapsid, with a weight of 700–1000 kg, and a length of about 5 meters.

Reptiles (Reptilia)

- Crocodilians (Crocodilia)

The largest known crocodilian is likely Sarcosuchus imperator at 12 metres (39 ft) long and weighing 8 tonnes.[27] Some close contenders in size are Deinosuchus estimated at around 12 metres (39 ft),[28] and Purussaurus estimated at 11–13 metres (36–43 ft) in length.[29] Another large crocodilian is Rhamphosuchus, estimated at 10 metres (33 ft) in length.[30] The largest terrestrial sebecid crocodilian is Barinasuchus, from the Miocene of South America, which reached 9 m (30 ft) long.

- Lizards & snakes (Squamata)

Giant mosasaurs are the largest animals within this group. The largest known mosasaur is likely Mosasaurus hoffmanni, estimated at 17.6 metres (58 ft) in length.[31] A close contender in size is Hainosaurus bernardi, estimated at 15 metres (49 ft) in length.[32] Another giant mosasaur is Tylosaurus, estimated at 10–14 metres (33–46 ft) in length.[33][34]

The largest known prehistoric snake is Titanoboa cerrejonensis, estimated at 13–15 metres (43–49 ft) in length and 1135 kg - 1819 kg in weight.[35] Another known very large fossil snake is Gigantophis garstini, estimated at around 11 metres (36 ft) in length.[36] However, a close rival in size to Gigantophis is a fossil snake, Palaeophis colossaeus, which may have been around 9 metres (30 ft) in length.[35][37]

The largest known land lizard is probably Megalania at 5.5 metres (18 ft) in length.[38][39] However, maximum size of this animal is subject to debate.[40]

- Long-Necked Plesiosaurs (Plesiosauria)

The largest plesiosaur was Mauisaurus haasti, growing to about 20 metres (66 ft) in length. Next behind was Elasmosaurus at 14 metres (46 ft) long.

- Pliosaurs (Pliosauroidea)

There is much controversy over the largest of these reptiles. Fossil remains of a pliosaur nicknamed as Predator X have been discovered and excavated from Norway in 2008. This pliosaur has been estimated at 15 metres (49 ft) in length and 41 metric tons (45 short tons) in weight.[41] However, in 2002, a team of paleontologists in Mexico discovered the remains of a pliosaur nicknamed as Monster of Aramberri, which is also estimated at 15 metres (49 ft) in length.[42] This specimen is however claimed to be a juvenile and has been attacked by a larger pliosaur.[43] Some media sources claimed that Monster of Aramberri was a Liopleurodon but its species is unconfirmed thus far.[42] Another very large pliosaur was Pliosaurus macromerus, known from a single 2.8 m long incomplete mandible. It may have reached 18 metres (59 ft), assuming the skull was about 17% of the total body length.[44]

- Ichthyosaurs (Ichthyosauria)

The largest ichthyosaur was Shastasaurus sikanniensis at 21 metres (69 ft) in length.[45]

- Turtles and tortoises (Testudines)

The largest turtle ever was Archelon ischyros at 16 ft long and 4,500 lbs[citation needed]. The next largest was Protostega at 3 m (10 ft).[46] Two tortoises share the title of largest ever tortoise: Meiolania at 8 ft. [citation needed]long and well over a ton, and Colossochelys atlas at 8 to 9 ft[citation needed]. and weighing over half a ton. The largest seems to be the freshwater turtle Stupendemys, with an estimated total carapace length of more than 3.3 m (11 ft) and weight of up to 1,814–2,268 kg (4,000–5,000 lb).[47] Carbonemys cofrinii has a shell that measures about 1.72 m (5.7 ft) and was estimated to weigh 916 kg (2016 lb).[48][49][50]

- Pareiasaurs (Pareiasauridae)

The largest is Scutosaurus, up to 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) in length, with bony armor, and a number of spikes decorating its skull.

- Phytosaurs (Phytosauria)

The largest of this order is Redondasaurus, who attained a length of 10–12 metres (32–40 ft)

- Pterosaurs (Pterosauria)

The largest pterosaur was Quetzalcoatlus northropi, at 127 kg (280 lbs) and with a wingspan of 12 m (40 ft). Another close contender is Hatzegopteryx, also with a wingspan of 12 m (this estimate is based on a skull 3 m long (10 ft).[51] Yet another possible contender for the title is Ornithocheirus, which allegedly had a 12-meter (40-foot) wingspan. However specimen of this size have not been formally described in the literature.

Non-avian dinosaurs (Dinosauria)

- Sauropods (Sauropoda)

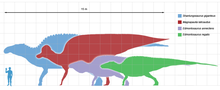

A mega-sauropod, Amphicoelias fragillimus, is a contender for the largest dinosaur in history. It has been estimated at 58 metres (190 ft) in length and 122,400 kilograms (269,800 lb) in weight.[52] Unfortunately, the fossil remains of this dinosaur have been lost.[52] This leaves sauropods like Argentinosaurus, Futalognkosaurus and Puertasaurus as the most possible contenders for the largest sauropod with estimated lengths of 30–35 metres (98–115 ft) and weights of 60–100 metric tons (66–110 short tons). Other giant sauropods like Supersaurus, Sauroposeidon, and Diplodocus probably rivaled them in length but not overall size.[52]

- Theropods (Theropoda)

The largest theropod as well as the largest terrestrial predator yet known is Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, with the largest specimen known estimated at 16–18 metres (52–59 ft) in length and around 7–9 metric tons (8–10 short tons) in weight.[53] Other large therapods were Giganotosaurus carolinii, and Tyrannosaurus rex, whose largest specimens known estimated at 13.2 metres (43 ft)[54] and 12.8 metres (42 ft)[55] in length respectively. Some other notable giant theropods (e.g. Carcharodontosaurus, Acrocanthosaurus, and Mapusaurus) may also have rivaled them in size.

-

- Armoured dinosaurs (Thyreophora)

- The largest thyreophoran was Ankylosaurus at 9 metres (30 ft) in length and 6.5 tons in weight.[56] Stegosaurus was also 9 meters (30 ft) long but around 5 tons in weight.

- Ceratopsians (Ceratopsia)

- The largest ceratopsian known is Triceratops horridus, along with the closely related Eotriceratops xerinsularis both with estimated lengths of 9 metres (30 ft).[57]

- Ornithopods (Ornithopoda)

- The very largest ornithopods, like Shantungosaurus were as heavy as medium sized sauropods at up to 23 metric tons. (25 short tons)[58][59] The largest is probably Shantungosaurus at 16.5 metres (54 ft) in length.[58] However, Magnapaulia laticauda appears to be close contender at around 15–16.4 metres (49–54 ft) in length.[59]

Birds (Aves)

The largest birds of all time might have been the elephant birds of Madagascar. Of almost the same size was the Australian Dromornis stirtoni. Both were about 3 m tall (10 ft). The elephant birds were up to 400 kg and Dromornis stirtoni was up to 500 kg in weight. The tallest bird ever was the Giant Moa (Dinornis maximus) at 12 ft tall.

The largest flight-capable bird was Argentavis magnificens which a wingspan of 8.3 m (28 ft), and a body weight of 110 kg (244 lb).

- Waterfowl (Anseriformes)

The largest waterfowl of all time belonged to the Dromornithidae (e.g. Dromornis stirtoni).[60]

- Shorebirds (Charadriiformes)

The largest shorebird of all time was the Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) at 5 kg (11 lb) in weight and 75–85 cm (30–34 in) in length.

- Storks & allies (Ciconiiformes)

The largest of Ciconiiformes was Leptoptilos robustus, standing 1.8 metres (5.9 ft) tall and weighing an estimated 16 kilograms (35 lb).[61][62]

- Falconiforms (Falconiformes)

The largest falconiform and the largest flying bird presently known was Argentavis magnificens. The immense bird had wingspan estimated up to 8.3 m (28 ft) and a weight up to 110 kg (244 lb). It was as high as an adult human when standing.

- Pigeons (Columbiformes)

The largest pigeon ever was the Dodo (Raphus cucullatus), weighing 23 kg (50 lb) and standing 1 m (3.3 ft) tall. Rodrigues solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria), a brown, long-necked birds that were superficially ratite-like. All three species may have exceeded 1 m (3.3 ft) in height. All were carelessly hunted it into extinction by humans and introduced animals. The Dodo is the most frequently crowned as the largest ever pigeon, as it could have weighed as much as 28 kg (62 lb), although recent estimates have indicated that an average wild Dodo would have weighed around 10.2 kg (22.5 lb), scarcely larger than a male turkey.[63][64] If Dodos were this light, the Rodrigues solitaire may have been larger. Some estimates claim tha solitaire was merely swan-sized but others estimate weights of up to 27.8 kg (61.2 lb).[65][66]

- Hesperornithines (Hesperornithes)

The largest of the hesperornithines was Canadaga arctica at 5 ft long.

- Diatrymas (Gastornithiformes)

The largest diatryma was Gastornis 1.75 metres (5.7 ft) tall, with large individuals up to 2 m (6.6 ft) tall.

- Teratorns (Teratornithidae)

The largest teratorn and the largest flying bird ever was Argentavis, with a weight of 80 kilograms (180 lb).

- Phorusrhacids (Phorusrhacidae)

The largest ever gruiform and largest phorusrhacid or "terror bird" (highly predatory, flightless birds of South America) was Brontornis, which was about 175 cm tall at the shoulder, could raise its head 2,8 metres above the ground an could have weighed as uch as 400 kg.[67] The immense phorushacid Kelenken with a skull 28 inches (71 cm) long (18 inches of which was beak), had the largest head of any known bird.

- Accipitriforms (Accipitriformes)

The largest bird of prey ever was the enormous Haast's eagle (Harpagornis moorei), with a wingspan of 2.6 to 3 m (8 to 10 ft), relatively short for their size. Total length was probably up to 1.4 m (4.7 ft) in female and they weighed about 10 to 15 kg (22 to 33 Ib).

- Gamebirds (Galliformes)

The largest in this group was a giant flightless Sylviornis, a bird 1.70 m (5.6 ft) long and weighing up to about 30 kg (66 lb).

- Songbirds (Passeriformes)

The largest songbird is the extinct Giant Grosbeak (Chloridops regiskongi) at 11 inches (28 cm) long.

- Cormorants and allies (Pelecaniformes)

The largest cormorants Spectacled Cormorant of the North Pacific (Phalacrocorax perspicillatus), which went extinct around 1850, was larger still, averaging around 6.4 kg (14 lb) and 1.15 m (3.8 ft).[68]

- Bony-toothed birds (Odontopterygiformes)

The largest in this group – which has been variously allied with Procellariiformes, Pelecaniformes and Anseriformes – and the largest flying birds of all time other than Argentavis were the huge Cyphornis, Dasornis, Gigantornis and Osteodontornis. They had a wingspan of 5.5–6 m (18–20 ft) and stood about 1.2 meters (4.5 ft) tall. Exact size estimates and judging which one was largest are not yet possible for these birds, as their bones were extremely thin-walled, light and fragile, and thus most are only known from very incomplete remains.

- Woodpeckers and allies (Piciformes)

The largest woodpecker is the possibly extinct Imperial Woodpecker (Campephilus imperialis) with a total length of about 22 inches (50 centimeters). The largest woodpecker confirmed to be extant is the Great Slaty Woodpecker (Mulleripicus pulverulentus).

- Parrots (Psittaciformes)

The largest parrot is the extinct Norfolk Island Kaka (Nestor productus), about 38 cm long.

- Penguins (Sphenisciformes)

The largest penguin of all time was Anthropornis nordenskjoeldi of New Zealand and Antarctica. It stood 1.7 meters (5 ft 6.9 in) in height and was 90 kilograms (198 lb) in weight. Similar in size were the New Zealand Giant Penguin (Pachydyptes pondeorsus) with a height of 1.4 to 1.6 m (about 5 ft) and weighing around 80 to possibly over 100 kg, and Icadyptes salasi at 1.5 m (5 ft) tall.

- Owls (Strigiformes)

The largest owl of all time was the Cuban Ornimegalonyx at 43.3 inches tall probably exceeding 9 kg (20 lb).[69]

Amphibians (Amphibia)

The largest amphibian of all time was the 30 ft long temnospondyli Prionosuchus. Another huge temnospondyli was Koolasuchus at 16 ft long, but only 1 ft high.

- Frogs (Anura)

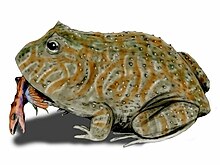

The largest frog ever was the 16-inch-long (41 cm) Beelzebufo ampinga, weighing 10 pounds (4.5 kg)

- Diadectomorpha

The largest diacectid, Diadectes, was a heavily built animal, 1.5 to 3 meters long, with thick vertebrae and ribs.

- Anthracosauria

The largest anthracosaur was Anthracosaurus, a predator. It could reach up to 12 feet in length. Eogyrinus commonly reached 4.6 metres (15 ft), however, it was more lightly built.[70]

Bony fish (Osteichthyes)

- Placoderms (Placodermi)

The largest placoderm was the 8.5 metres (28 ft) long Dunkleosteus. Its relative, Titanichthys, may have rivaled it in size. These particular animals may have reached lengths of 10 m (33 ft) and are estimated to have weighed in at 3.6 tons.

- Lobe-finned fish (Sarcopterygii)

The largest of these was the 5 metres (16 ft) long Hyneria.

- Ray-finned fish (Actinopterygii)

The largest bony fish of all time was the pachycormid, Leedsichthys problematicus, at around 16 metres (52 ft) long.[71] Claims of larger individuals persist.

- Ichthyodectid (Ichthyodectidae)

The largest of ichthyodectid fish was the 5.0 metres (16.4 ft) long Xiphactinus .

Cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes)

- Mackerel sharks (Lamniformes)

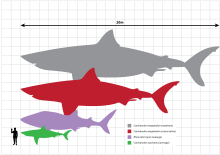

An extinct megatoothed shark, C. megalodon is by far the biggest shark known.[72] This giant shark reached a total length (TL) of more than 16 metres (52 ft).[73][74] C. megalodon may have approached a maximum of 20.3 metres (67 ft) in total length and 103 metric tons (114 short tons) in mass.[75]

- Symmoriid (Symmoriida)

The largest symmoriid is Stethacanthus at 2 metres (6.6 ft) long.

- Eugenedont (Eugenedonta)

The largest eugenedont is Helicoprion at 10 metres (33 ft) long.

- Hybodontiform (Hybodontiformes)

The largest hydontiformids is Ptychodus was about 32 feet long (10 meters)

Arthropods (Arthropoda)

- Radiodont (Radiodonta)

The largest known is Anomalocaris at 1 meter long.

- Eurypterids (Eurypterida)

The largest in this group was Jaekelopterus rhenaniae at 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) in length. A close contender was Pterygotus at 2.3 metres (7.5 ft) in length.

- Arachnids (Arachnida)

There are two contenders for largest ever arachnid: Pulmonoscorpius kirktonensis and Brontoscorpio anglicus. Both were 1 metre (3.3 ft). The biggest difference is that Brontoscorpio was aquatic, and Pulmonoscorpius was terrestrial. Brontoscorpio is not to be confused with various Eurypterids: it was a true scorpion with a stinger.

- Centipedes (Chilopoda)

The largest centipede of all time was Euphoberia at 1 metre (3.3 ft). It was about four times as long as the largest living species, Scolopendra gigantea.

- Millipedes (Diplopoda)

The largest by far was the giant Arthropleura. Measuring 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) and 45 centimetres (18 in) wide, it was the largest terrestrial arthropod of all time.

Trilobitomorpha

- Trilobites (Trilobita)

Some of these extinct marine arthropods exceeded 60 centimetres (24 in) in length. A nearly complete specimen of Isotelus rex from Manitoba attained a length over 70 centimetres (28 in), and an Ogyginus forteyi from Portugal was almost as long. Fragments of trilobites suggest even larger record sizes. An isolated pygidium of Hungioides bohemicus implies that the full animal was 90 centimetres (35 in) long.[76]

Insects (Insecta)

- Sawflies, wasps, bees, ants and allies (Hymenoptera)

The largest of this group was the giant ant Titanomyrma giganteum at 3 centimetres (1.2 in), with queens growing to 6 centimetres (2.4 in). It had a wingspan of 15 centimetres (5.9 in).[77]

- Protodonata

The largest in this group was probably Meganeura with a wingspan of 75 centimetres (2.46 ft).[78] Another enormous and possibly larger species was Meganeuropsis permiana.

- Siphonaptera

The largest in this group was probably Saurophthirus, growing to 1 inch (2.5 cm) in length. It possibly sucked the blood of pterosaurs.

- Palaeodictyoptera

The largest of this order was Mazothairos, with a wingspan of up to 22 inches (56 cm).

- Dictyoptera

Several cockroach-like stem dictyopterans from the Carboniferous Period grew to exceptional size. A specimen of Xenoblatta from Ohio was at least 70 mm long, almost the size of the largest cockroach living today.[79][80]

Molluscs (Mollusca)

Gastropods (Gastropoda)

- Snails and slugs (Gastropoda)

The largest of this group were in the genus Campanile, with the extinct Campanile giganteum having shell lengths up to 60 centimetres (24 in).

Bivalves (Bivalvia)

- Bivalves (Bivalvia)

The largest bivalve ever was Platyceramus platinus, a giant that usually had an axial length of 1 metre (3.3 ft), but some individuals could reach an axial length of up to 3 metres (9.8 ft).

Cephalopods (Cephalopoda)

- Ammonites (Ammonoidea)

The largest ammonite was Parapuzosia seppenradensis. A partial fossil specimen found in Germany had a shell diameter of 1.95 metres (6.4 ft), but the living chamber was incomplete, so the estimated shell diameter was probably about 2.55 metres (8.4 ft) when it was alive.

- Belemnites (Belemnoidea)

The largest belemnite was Megateuthis gigantea with a guard of 46 centimetres (18 in) in length and an estimated total length 3 metres (9.8 ft) long.

- Nautiloids (Nautiloidea)

The longest and largest of this group was Cameroceras with a shell length of 9 metres (30 ft).[81]

- Neocoleoidea

Both Tusoteuthis and Yezoteuthis are estimated to be similar in size to the modern day giant squid.[82]

See also

References

- ^ Carbone, Chris; Teacher, Amber; Rowcliffe, J (2007). "The Costs of Carnivory". PLoS Biology. 5 (2): e22. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050022. PMC 1769424. PMID 17227145. Retrieved 2009-12-28.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Hokkanen, J.E.I. (21 February 1986). "The size of the largest land animal". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 118 (4). Elsevier Ltd: 491–499. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(86)80167-9. PMID 3713220. Department of Theoretical Physics, University of Helsinki.

- ^ "Sea Monsters - Fact File: Basilosaurus". BBC - Science & Nature. c.2003. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lambert, Olivier (1 July 2010). "The giant bite of a new raptorial sperm whale from the Miocene epoch of Peru". Nature. 466 (7302). Peru: Nature: 105–108. doi:10.1038/nature09067. PMID 20596020. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Perkins, Sid (2010-07-31). "Moby Dick Meets Jaws. Extinct Whale had Teeth Bigger than T. rex's". Science News. 178 (3): 17. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "The Jaws of the Leviathan". Nature Video. c.2010. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Deméré, Thomas A.; Berta, Annalisa; McGowen, Michael R. (2005). "The taxonomic and evolutionary history of fossil and modern balaenopteroid mysticetes". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 12 (1/2): 99–143. doi:10.1007/s10914-005-6944-3.

- ^ Giant Camel Disappeared Species. Intechinc.com (2011-07-05)

- ^ Mendoza, M.; Janis, C. M.; Palmqvist, P. (2006). "Estimating the body mass of extinct ungulates: a study on the use of multiple regression". Journal of Zoology. 270 (1): 90–101.

- ^ Teeth: Kubanochoerus gigas lii (GUAN). tesorosnaturales.es

- ^ David Petersen. Of Moose, Megaloceros and Miracles. Motherearthnews.com (1989-03-01)

- ^ Ice Age Marsupial Topped Three Tons, Scientists Say, 2003-09-17. Retrieved 2003-09-17.

- ^ Helgen, K.M., Wells, R.T., Kear, B.P., Gerdtz, W.R., and Flannery, T.F. (2006). "Ecological and evolutionary significance of sizes of giant extinct kangaroos". Australian Journal of Zoology. 54: 293–303. doi:10.1071/ZO05077.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dell'Amore, C. (2011): Biggest Bear Ever Found, National Geographic News, Published February 3, 2011

- ^ Alan Turner, National Geographic Prehistoric Mammals National Geographic, 2004, ISBN 0792271343

- ^ Paul S Martin (1984). Quaternary Extinctions. The University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-1100-4.

- ^ http://www.app.pan.pl/archive/published/app56/app20100005.pdf

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(96)80005-2, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/S0016-6995(96)80005-2instead. - ^ Villier, Boris (2010). "Deinogalerix: a giant hedgehog from the Miocene". Annali dell’Università di Ferrara. 6: 93–102. ISSN 1824-2707.

- ^ Ciochon, Russell L. "The Ape that Was - Asian fossils reveal humanity's giant cousin". University of Iowa. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ^ Pettifor, Eric (2000) [1995]. "From the Teeth of the Dragon: Gigantopithecus Blacki". Selected Readings in Physical Anthropology. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. pp. 143–149. ISBN 0-7872-7155-1. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- ^ Osborn, H. F. (1942). Proboscidea, Vol. II. New York: The American Museum Press.

- ^ Rinderknecht, Andrés (2008-01-15). "The largest fossil rodent" (pdf). Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences. 275 (1637): 923–8. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1645. PMC 2599941. PMID 18198140. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ Gingerich, Philip D. (1998). "Paleobiological Perspectives on Mesonychia, Archaeoceti, and the Origin of Whales". In Thewissen, J.G.M. (ed.). The emergence of whales: evolutionary patterns in the origin of Cetacea. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 423–450. ISBN 978-0-306-45853-8.

- ^ Sorkin, B. (2008). "A biomechanical constraint on body mass in terrestrial mammalian predators". Lethaia. 41: 333–347.

- ^ Benton, M.J. (2005). Vertebrate Palaeontology. Oxford, 333.

- ^ Lyon, Gabrielle. "Fact Sheet". SuperCroc. Project Exploration. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ^ Lucas, Spencer G. (2006). "The Giant Crocodylian Deinosuchus from the Upper Cretaceous of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico" (PDF). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 35. Mexico. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) [dead link] - ^ Bocquentin, Jean; Melo, Janira (2006). "Stupendemys souzai sp. nov. (Pleurodira, Podocnemididae) from the Miocene-Pliocene of the Solimões Formation, Brazil" (PDF). Sociedade Brasileira de Paleontologia. 9 (2): 187–192. doi:10.4072/rbp.2006.2.02.

- ^ Head, J. J. (2001). "Systematics and body size of the gigantic, enigmatic crocodyloid Rhamphosuchus crassidens, and the faunal history of Siwalik Group (Miocene) crocodylians". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (Supplement to No. 3): 59A.

- ^ Dortangs, Rudi W. (2002). "A large new mosasaur from the Upper Cretaceous of The Netherlands" (PDF). Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 81 (1). Netherlands: 1–8. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lingham-Soliar, Theagarten (1995). "Copyright: Anatomy and Functional Morphology of the Largest Marine Reptile Known, Mosasaurus hoffmanni (Mosasauridae, Reptilia) from the Upper Cretaceous, Upper Maastrichtian of the Netherlands". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 347: 155–172. doi:10.1098/rstb.1995.0019.

- ^ Everhart, Mike. "Research: Tylosaurus proriger - A new record of a large mosasaur from the Smoky Hill Chalk". Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ "Fact File: Tylosaurus Proriger from National Geographic". Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ a b Head, Jason J. (5 February 2009). "Giant boid snake from the Palaeocene neotropics reveals hotter past equatorial temperatures" (PDF). Nature. 457 (7230). Colombia: Macmillan Publishers Limited: 715–717. doi:10.1038/nature07671. PMID 19194448. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Roach, John (February 4, 2009). "Biggest Snake Discovered; Was Longer Than a Bus". National Geographic News. USA.

- ^ Rage, Jean-Claude (2003). "Early Eocene snakes from Kutch, Western India, with a review of the Palaeophiidae" (PDF). Geodiversitas. 25 (4). India: Editions scientifiques du Muséum, Paris, FRANCE: 695–716. ISSN 1280-9659. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Megalania, giant ripper lizard". Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ "Lost Tapes: Megalania". Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ "Review of DRAGONS IN THE DUST: THE PALEOBIOLOGY OF THE GIANT MONITOR LIZARD MEGALANIA, by Ralph E. Molnar, 2004 in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25(2):479, June 2005" (PDF). Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ Predator X (TV). Norway: History Channel. 2008.

- ^ a b Buchy, M.-C.; Frey, E.; Stinnesbeck, W.; López-Oliva, J.G. (2003). "First occurrence of a gigantic pliosaurid plesiosaur in the late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian) of Mexico". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 174 (3): 271–278. doi:10.2113/174.3.271.

- ^ "Monster von Arramberri". Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ^ "The Cumnor monster mandible". Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ "Triassic Giant". Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ Lutz, Peter L. (1996). The Biology of Sea Turtles. CRC Press. p. 432pp. ISBN 0-8493-8422-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Afro-American River Turtles: Podocnemididae – Behavior And Reproduction. animals.jrank.org

- ^ Researchers reveal ancient giant turtle fossil. Phys.org (2012-05-17)

- ^ Maugh II, Thomas H. (2012-05-18). "Researchers find fossil of a turtle that was size of a Smart car". LA Times.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Buffetaut, E.; Grigorescu, D.; Csiki, Z. (2002). "A new giant pterosaur with a robust skull from the latest Cretaceous of Romania". Naturwissenschaften. 89 (4): 180–184. doi:10.1007/s00114-002-0307-1. PMID 12061403.

- ^ a b c Carpenter, K. (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus." In Foster, J.R. and Lucas, S.G., eds., 2006, Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36: 131–138.

- ^ dal Sasso, C. (2005). "New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod Spinosaurus, with remarks on its sizes and affinities". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (4): 888–896. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0888:NIOTSO]2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Calvo, Jorge O.; Coria, Rodolfo (1998). "New specimen of Giganotosaurus Carolinii" (PDF). GAIA: 117–122.

- ^ Henderson DM (January 1, 1999). "Estimating the masses and centers of mass of extinct animals by 3-D mathematical slicing". Paleobiology. 25 (1): 88–106.

- ^ Vickaryous, M.K., Maryanska, T., & Weishampel, D.B. 2004. Ankylosauria. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., & Osmólska, H. (Eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 363-392.

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2008). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. New York: Random House. pp. 52, updated appendix. ISBN 0-375-82419-7.

- ^ a b Zhao, X. (2007). "Zhuchengosaurus maximus from Shandong Province". Acta Geoscientia Sinica. 28 (2): 111–122. doi:10.1007/s10114-005-0808-x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Morris, William J. (1981). "A new species of hadrosaurian dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Baja California: ?Lambeosaurus laticaudus". Journal of Paleontology. 55 (2): 453–462.

- ^ "Dromornis stirtoni". Australian Museum.

- ^ BBC - Earth News - Giant fossil bird found on 'hobbit' island of Flores

- ^ Meijer HJM & R A Due (2010). "A new species of giant marabou stork (Aves: Ciconiiformes) from the Pleistocene of Liang Bua, Flores (Indonesia)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 160: 707–724. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00616.x.

- ^ Nature: An Economic History by Geerat J. Vermeij. Princeton University Press (2004), ISBN 0691115273

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ "Systematic revision of the Phorusrhacidae (Aves: Ralliformes)".

- ^ California Academy of Sciences – Science Under Sail. Calacademy.org

- ^ Arredondo, Oscar (1976) translated Olson, Storrs L. The Great Predatory Birds of the Pleistocene of Cuba pp. 169-187 in "Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology number 27; Collected Papers in Avian Paleontology Honoring the 90th Birthday of Alexander Wetmore"

- ^ Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 53. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ^ Liston, Jeff. "Big Dead Fish, or just Big Dead-in-the-Water Ideas?". Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ^ deGruy, Michael (2006). Perfect Shark (TV-Series). BBC.

{{cite AV media}}: Unknown parameter|country=ignored (help) - ^ Klimley, Peter; Ainley, David (1996). Great White Sharks: The Biology of Carcharodon carcharias. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-415031-4.

- ^ Pimiento, Catalina (May 10, 2010). Stepanova, Anna (ed.). "Ancient Nursery Area for the Extinct Giant Shark Megalodon from the Miocene of Panama". PLoS ONE. 5 (5). Panama: PLoS.org: e10552. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010552. PMC 2866656. PMID 20479893.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Wroe, S. (2008). "Three-dimensional computer analysis of white shark jaw mechanics: how hard can a great white bite?". Journal of Zoology. 276 (4): 336–342. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00494.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gutiérrez-Marco, Juan C.; Sá, Artur A.; Garcia-Bellido, Diego C.; Rabano, Isabel; Valério, Manuel (2009). "Giant Trilobites and Trilobite Clusters from the Ordovician of Portugal". Geology. 37: 443−446. doi:10.1130/G25513A.1.

- ^ Schaal, Stephan (27 Jan 2006). "Messel". doi:10.1038/npg.els.0004143.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Dragonfly: the largest complete insect wing ever found", Harvard Magazine November–December 2007:112.

- ^ Svitil, Kathy A. (2003-12-08). "The First Spinners". Discover. Retrieved 2010-09-09.

- ^

Easterday, Cary R. (2003). "Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, ," (Document). Seattle, Washington: Geological Society of America. p. 538.

{{cite document}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|editor-last=and|editor-first=(help); Unknown parameter|contribution=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|issue=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|volume=ignored (help) - ^ Teichert C and B Kummel (1960). "Size of Endocerid Cephalopods". Breviora Mus. Comp. Zool. 128: 1–7.

- ^ http://www.tonmo.com/science/fossils/cretaceousGS.php