DNA sequencing

| Part of a series on |

| Genetics |

|---|

|

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the precise order of nucleotides within a DNA molecule. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases—adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine—in a strand of DNA. The advent of rapid DNA sequencing methods has greatly accelerated biological and medical research and discovery.

Knowledge of DNA sequences has become indispensable for basic biological research, and in numerous applied fields such as diagnostic, biotechnology, forensic biology, and biological systematics. The rapid speed of sequencing attained with modern DNA sequencing technology has been instrumental in the sequencing of complete DNA sequences, or genomes of numerous types and species of life, including the human genome and other complete DNA sequences of many animal, plant, and microbial species.

The first DNA sequences were obtained in the early 1970s by academic researchers using laborious methods based on two-dimensional chromatography. Following the development of fluorescence-based sequencing methods with automated analysis,[1] DNA sequencing has become easier and orders of magnitude faster.[2]

Use of sequencing

DNA sequencing may be used to determine the sequence of individual genes, larger genetic regions (i.e. clusters of genes or operons), full chromosomes or entire genomes. Depending on the methods used, sequencing may provide the order of nucleotides in DNA or RNA isolated from cells of animals, plants, bacteria, archaea, or virtually any other source of genetic information. The resulting sequences may be used by researchers in molecular biology or genetics to further scientific progress or may be used by medical personnel to make treatment decisions or aid in genetic counseling.

History

Though the structure of DNA was established as a double helix in 1953,[3] several decades would pass before fragments of DNA could be reliably analyzed for their sequence in the laboratory. RNA sequencing was one of the earliest forms of nucleotide sequencing. The major landmark of RNA sequencing is the sequence of the first complete gene and the complete genome of Bacteriophage MS2, identified and published by Walter Fiers and his coworkers at the University of Ghent (Ghent, Belgium), in 1972[4] and 1976.[5]

Several notable advancements in DNA sequencing were made during the 1970s. Frederick Sanger developed rapid DNA sequencing methods at the MRC Centre, Cambridge, UK and published a method for "DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors" in 1977.[6] Walter Gilbert and Allan Maxam at Harvard also developed sequencing methods, including one for "DNA sequencing by chemical degradation".[7][8] In 1973, Gilbert and Maxam reported the sequence of 24 basepairs using a method known as wandering-spot analysis.[9] Advancements in sequencing were aided by the concurrent development of recombinant DNA technology, allowing DNA samples to be isolated from sources other than viruses.

The first full DNA genome to be sequenced was that of bacteriophage φX174 in 1977.[10] Medical Research Council scientists deciphered the complete DNA sequence of the Epstein-Barr virus in 1984, finding it to be 170 thousand base-pairs long.

Leroy E. Hood's laboratory at the California Institute of Technology and Smith announced the first semi-automated DNA sequencing machine in 1986.[citation needed] This was followed by Applied Biosystems' marketing of the first fully automated sequencing machine, the ABI 370, in 1987. By 1990, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) had begun large-scale sequencing trials on Mycoplasma capricolum, Escherichia coli, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae at a cost of US$0.75 per base. Meanwhile, sequencing of human cDNA sequences called expressed sequence tags began in Craig Venter's lab, an attempt to capture the coding fraction of the human genome.[11] In 1995, Venter, Hamilton Smith, and colleagues at The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) published the first complete genome of a free-living organism, the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae. The circular chromosome contains 1,830,137 bases and its publication in the journal Science[12] marked the first published use of whole-genome shotgun sequencing, eliminating the need for initial mapping efforts. By 2001, shotgun sequencing methods had been used to produce a draft sequence of the human genome.[13][14]

Several new methods for DNA sequencing were developed in the mid to late 1990s. These techniques comprise the first of the "next-generation" sequencing methods. In 1996, Pål Nyrén and his student Mostafa Ronaghi at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm published their method of pyrosequencing.[15] A year later, Pascal Mayer and Laurent Farinelli submitted patents to the World Intellectual Property Organization describing DNA colony sequencing.[16] Lynx Therapeutics published and marketed "Massively parallel signature sequencing", or MPSS, in 2000. This method incorporated a parallelized, adapter/ligation-mediated, bead-based sequencing technology and served as the first commercially available "next-generation" sequencing method, though no DNA sequencers were sold to independent laboratories.[17] In 2004, 454 Life Sciences marketed a parallelized version of pyrosequencing.[18][19] The first version of their machine reduced sequencing costs 6-fold compared to automated Sanger sequencing, and was the second of the new generation of sequencing technologies, after MPSS.[20]

The large quantities of data produced by DNA sequencing have also required development of new methods and programs for sequence analysis. Phil Green and Brent Ewing of the University of Washington described their phred quality score for sequencer data analysis in 1998.[21]

Basic methods

Maxam-Gilbert sequencing

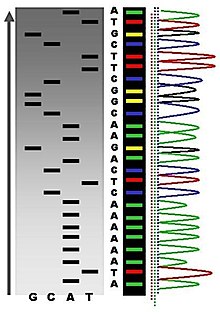

Allan Maxam and Walter Gilbert published a DNA sequencing method in 1977 based on chemical modification of DNA and subsequent cleavage at specific bases.[7] Also known as chemical sequencing, this method allowed purified samples of double-stranded DNA to be used without further cloning. This method's use of radioactive labeling and its technical complexity discouraged extensive use after refinements in the Sanger methods had been made.

Maxam-Gilbert sequencing requires radioactive labeling at one 5' end of the DNA and purification of the DNA fragment to be sequenced. Chemical treatment then generates breaks at a small proportion of one or two of the four nucleotide bases in each of four reactions (G, A+G, C, C+T). The concentration of the modifying chemicals is controlled to introduce on average one modification per DNA molecule. Thus a series of labeled fragments is generated, from the radiolabeled end to the first "cut" site in each molecule. The fragments in the four reactions are electrophoresed side by side in denaturing acrylamide gels for size separation. To visualize the fragments, the gel is exposed to X-ray film for autoradiography, yielding a series of dark bands each corresponding to a radiolabeled DNA fragment, from which the sequence may be inferred.[7]

Chain-termination methods

The chain-termination method developed by Frederick Sanger and coworkers in 1977 soon became the method of choice, owing to its relative ease and reliability.[6][22] The chain-terminator method uses fewer toxic chemicals and lower amounts of radioactivity than the Maxam and Gilbert method. Because of its comparative ease, the Sanger method was soon automated and was the method used in the first generation of DNA sequencers.

Advanced methods and de novo sequencing

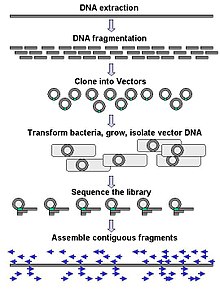

Large-scale sequencing often aims at sequencing very long DNA pieces, such as whole chromosomes, although large-scale sequencing can also be used to generate very large numbers of short sequences, such as found in phage display. For longer targets such as chromosomes, common approaches consist of cutting (with restriction enzymes) or shearing (with mechanical forces) large DNA fragments into shorter DNA fragments. The fragmented DNA may then be cloned into a DNA vector and amplified in a bacterial host such as Escherichia coli. Short DNA fragments purified from individual bacterial colonies are individually sequenced and assembled electronically into one long, contiguous sequence.

The term "de novo sequencing" specifically refers to methods used to determine the sequence of DNA with no previously known sequence. De novo translates from Latin as "from the beginning". Gaps in the assembled sequence may be filled by primer walking. The different strategies have different tradeoffs in speed and accuracy; shotgun methods are often used for sequencing large genomes, but its assembly is complex and difficult, particularly with sequence repeats often causing gaps in genome assembly.

Most sequencing approaches use an in vitro cloning step to amplify individual DNA molecules, because their molecular detection methods are not sensitive enough for single molecule sequencing. Emulsion PCR[23] isolates individual DNA molecules along with primer-coated beads in aqueous droplets within an oil phase. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) then coats each bead with clonal copies of the DNA molecule followed by immobilization for later sequencing. Emulsion PCR is used in the methods developed by Marguilis et al. (commercialized by 454 Life Sciences), Shendure and Porreca et al. (also known as "Polony sequencing") and SOLiD sequencing, (developed by Agencourt, later Applied Biosystems, now Life Technologies).[24][25][26]

Shotgun sequencing

Shotgun sequencing is a sequencing method designed for analysis of DNA sequences longer than 1000 base pairs, up to and including entire chromosomes. This method requires the target DNA to be broken into random fragments. After sequencing individual fragments, the sequences can be reassembled on the basis of their overlapping regions.[27]

Bridge PCR

Another method for in vitro clonal amplification is bridge PCR, in which fragments are amplified upon primers attached to a solid surface [16][28][29] and form "DNA colonies" or "DNA clusters". This method is used in the Illumina Genome Analyzer sequencers. Single-molecule methods, such as that developed by Stephen Quake's laboratory (later commercialized by Helicos) are an exception: they use bright fluorophores and laser excitation to detect base addition events from individual DNA molecules fixed to a surface, eliminating the need for molecular amplification.[30]

Next-generation methods

The high demand for low-cost sequencing has driven the development of high-throughput sequencing (or next-generation sequencing) technologies that parallelize the sequencing process, producing thousands or millions of sequences at once.[31][32] High-throughput sequencing technologies are intended to lower the cost of DNA sequencing beyond what is possible with standard dye-terminator methods.[20] In ultra-high-throughput sequencing as many as 500,000 sequencing-by-synthesis operations may be run in parallel.[33][34][35]

| Method | Single-molecule real-time sequencing (Pacific Bio) | Ion semiconductor (Ion Torrent sequencing) | Pyrosequencing (454) | Sequencing by synthesis (Illumina) | Sequencing by ligation (SOLiD sequencing) | Chain termination (Sanger sequencing) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Read length | 2900 bp average[38] | 200 bp | 700 bp | 50 to 250 bp | 50+35 or 50+50 bp | 400 to 900 bp |

| Accuracy | 87% (read length mode), 99% (accuracy mode) | 98% | 99.9% | 98% | 99.9% | 99.9% |

| Reads per run | 35–75 thousand [39] | up to 5 million | 1 million | up to 3 billion | 1.2 to 1.4 billion | N/A |

| Time per run | 30 minutes to 2 hours [40] | 2 hours | 24 hours | 1 to 10 days, depending upon sequencer and specified read length[41] | 1 to 2 weeks | 20 minutes to 3 hours |

| Cost per 1 million bases (in US$) | $2 | $1 | $10 | $0.05 to $0.15 | $0.13 | $2400 |

| Advantages | Longest read length. Fast. Detects 4mC, 5mC, 6mA.[42] | Less expensive equipment. Fast. | Long read size. Fast. | Potential for high sequence yield, depending upon sequencer model and desired application. | Low cost per base. | Long individual reads. Useful for many applications. |

| Disadvantages | Low yield at high accuracy. Equipment can be very expensive. | Homopolymer errors. | Runs are expensive. Homopolymer errors. | Equipment can be very expensive. | Slower than other methods. | More expensive and impractical for larger sequencing projects. |

Massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS)

The first of the next-generation sequencing technologies, massively parallel signature sequencing (or MPSS), was developed in the 1990s at Lynx Therapeutics, a company founded in 1992 by Sydney Brenner and Sam Eletr. MPSS was a bead-based method that used a complex approach of adapter ligation followed by adapter decoding, reading the sequence in increments of four nucleotides. This method made it susceptible to sequence-specific bias or loss of specific sequences. Because the technology was so complex, MPSS was only performed 'in-house' by Lynx Therapeutics and no DNA sequencing machines were sold to independent laboratories. Lynx Therapeutics merged with Solexa (later acquired by Illumina) in 2004, leading to the development of sequencing-by-synthesis, a more simple approach which rendered MPSS obsolete. However, the essential properties of the MPSS output were typical of later "next-generation" data types, including hundreds of thousands of short DNA sequences. In the case of MPSS, these were typically used for sequencing cDNA for measurements of gene expression levels.[43]

Polony sequencing

The Polony sequencing method, developed in the laboratory of George M. Church at Harvard, was among the first next-generation sequencing systems and was used to sequence a full genome in 2005. It combined an in vitro paired-tag library with emulsion PCR, an automated microscope, and ligation-based sequencing chemistry to sequence an E. coli genome at an accuracy of >99.9999% and a cost approximately 1/9 that of Sanger sequencing.[44] The technology was licensed to Agencourt Biosciences, subsequently spun out into Agencourt Personal Genomics, and eventually incorporated into the Applied Biosystems SOLiD platform, which is now owned by Life Technologies.

454 pyrosequencing

A parallelized version of pyrosequencing was developed by 454 Life Sciences, which has since been acquired by Roche Diagnostics. The method amplifies DNA inside water droplets in an oil solution (emulsion PCR), with each droplet containing a single DNA template attached to a single primer-coated bead that then forms a clonal colony. The sequencing machine contains many picoliter-volume wells each containing a single bead and sequencing enzymes. Pyrosequencing uses luciferase to generate light for detection of the individual nucleotides added to the nascent DNA, and the combined data are used to generate sequence read-outs.[24] This technology provides intermediate read length and price per base compared to Sanger sequencing on one end and Solexa and SOLiD on the other.[20]

Illumina (Solexa) sequencing

Solexa, now part of Illumina, developed a sequencing method based on reversible dye-terminators technology, and engineered polymerases, that it developed internally.[45] The terminated chemistry was developed internally at Solexa and the concept of the Solexa system was invented by Balasubramanian and Klennerman from Cambridge University's chemistry department. In 2005, Solexa acquired the company Manteia in order to gain a technology called "Clusters", which involves the clonal amplification of DNA on a surface. The cluster technology was co-acquired with Lynx Therapeutics of California. Solexa Ltd. later merged with Lynx to form Solexa Inc.

In this method, DNA molecules and primers are first attached on a slide and amplified with polymerase so that local clonal colonies, initially coined "clusters", are formed. To determine the sequence, four types of reversible terminator bases (RT-bases) are added and non-incorporated nucleotides are washed away. A camera takes images of the fluorescently labeled nucleotides, then the dye along with the terminal 3' blocker is chemically removed from the DNA, allowing the next cycle. Unlike pyrosequencing, the DNA chains are extended one nucleotide at a time and image acquisition can be performed at a delayed moment, allowing for very large arrays of DNA colonies to be captured by sequential images taken from a single camera.

Decoupling the enzymatic reaction and the image capture allows for optimal throughput and theoretically unlimited sequencing capacity. With an optimal configuration, the ultimately reachable instrument throughput is thus dictated solely by the analog-to-digital conversion rate of the camera, multiplied by the number of cameras and divided by the number of pixels per DNA colony required for visualizing them optimally (approximately 10 pixels/colony). In 2012, with cameras operating at more than 10 MHz A/D conversion rates and available optics, fluidics and enzymatics, throughput can be multiples of 1 million nucleotides/second, corresponding roughly to 1 human genome equivalent at 1x coverage per hour per instrument, and 1 human genome re-sequenced (at approx. 30x) per day per instrument (equipped with a single camera).[46]

SOLiD sequencing

Applied Biosystems' (now a Life Technologies brand) SOLiD technology employs sequencing by ligation. Here, a pool of all possible oligonucleotides of a fixed length are labeled according to the sequenced position. Oligonucleotides are annealed and ligated; the preferential ligation by DNA ligase for matching sequences results in a signal informative of the nucleotide at that position. Before sequencing, the DNA is amplified by emulsion PCR. The resulting beads, each containing single copies of the same DNA molecule, are deposited on a glass slide.[47] The result is sequences of quantities and lengths comparable to Illumina sequencing.[20]

Ion semiconductor sequencing

Ion Torrent Systems Inc. (now owned by Life Technologies) developed a system based on using standard sequencing chemistry, but with a novel, semiconductor based detection system. This method of sequencing is based on the detection of hydrogen ions that are released during the polymerisation of DNA, as opposed to the optical methods used in other sequencing systems. A microwell containing a template DNA strand to be sequenced is flooded with a single type of nucleotide. If the introduced nucleotide is complementary to the leading template nucleotide it is incorporated into the growing complementary strand. This causes the release of a hydrogen ion that triggers a hypersensitive ion sensor, which indicates that a reaction has occurred. If homopolymer repeats are present in the template sequence multiple nucleotides will be incorporated in a single cycle. This leads to a corresponding number of released hydrogens and a proportionally higher electronic signal.[48]

DNA nanoball sequencing

DNA nanoball sequencing is a type of high throughput sequencing technology used to determine the entire genomic sequence of an organism. The company Complete Genomics uses this technology to sequence samples submitted by independent researchers. The method uses rolling circle replication to amplify small fragments of genomic DNA into DNA nanoballs. Unchained sequencing by ligation is then used to determine the nucleotide sequence.[49] This method of DNA sequencing allows large numbers of DNA nanoballs to be sequenced per run and at low reagent costs compared to other next generation sequencing platforms.[50] However, only short sequences of DNA are determined from each DNA nanoball which makes mapping the short reads to a reference genome difficult.[51] This technology has been used for multiple genome sequencing projects and is scheduled to be used for more.[52]

Heliscope single molecule sequencing

Heliscope sequencing is a method of single-molecule sequencing developed by Helicos Biosciences. It uses DNA fragments with added poly-A tail adapters which are attached to the flow cell surface. The next steps involve extension-based sequencing with cyclic washes of the flow cell with fluorescently labeled nucleotides (one nucleotide type at a time, as with the Sanger method). The reads are performed by the Heliscope sequencer. The reads are short, up to 55 bases per run, but recent improvements allow for more accurate reads of stretches of one type of nucleotides.[53][54]

This sequencing method and equipment were used to sequence the genome of the M13 bacteriophage.[55]

Single molecule real time (SMRT) sequencing

SMRT sequencing is based on the sequencing by synthesis approach. The DNA is synthesized in zero-mode wave-guides (ZMWs) – small well-like containers with the capturing tools located at the bottom of the well. The sequencing is performed with use of unmodified polymerase (attached to the ZMW bottom) and fluorescently labelled nucleotides flowing freely in the solution. The wells are constructed in a way that only the fluorescence occurring by the bottom of the well is detected. The fluorescent label is detached from the nucleotide at its incorporation into the DNA strand, leaving an unmodified DNA strand. According to Pacific Biosciences, the SMRT technology developer, this methodology allows detection of nucleotide modifications (such as cytosine methylation). This happens through the observation of polymerase kinetics. This approach allows reads of up to 15,000 nucleotides, with mean read lengths of 2.5 to 2.9 kilobases.[38]

One problem with sequencing by synthesis techniques is the difficulty in sequencing homopolymers, which are repeats of a single nucleotide. One way to detect these repeats is by analyzing the intensity of fluorescence. Due to interference between fluorophores from multiple molecules, light intensity decreases with increasing homopolymer length. For example, the addition of two cytosines emits less light than the addition of one cytosine. This method has high accuracy for detecting repeats of up to four nucleotides. Though the accuracy decreases for longer repeats, these repeats are much rarer in genes.[56]

Methods in development

DNA sequencing methods currently under development include labeling the DNA polymerase,[57] reading the sequence as a DNA strand transits through nanopores,[58][59] and microscopy-based techniques, such as atomic force microscopy or transmission electron microscopy that are used to identify the positions of individual nucleotides within long DNA fragments (>5,000 bp) by nucleotide labeling with heavier elements (e.g., halogens) for visual detection and recording.[60][61] Third generation technologies aim to increase throughput and decrease the time to result and cost by eliminating the need for excessive reagents and harnessing the processivity of DNA polymerase.[62]

Nanopore DNA sequencing

This method is based on the readout of electrical signals occurring at nucleotides passing by alpha-hemolysin pores covalently bound with cyclodextrin. The DNA passing through the nanopore changes its ion current. This change is dependent on the shape, size and length of the DNA sequence. Each type of the nucleotide blocks the ion flow through the pore for a different period of time. The method has a potential of development as it does not require modified nucleotides, however single nucleotide resolution is not yet available.[63]

Sequencing by hybridization

Sequencing by hybridization is a non-enzymatic method that uses a DNA microarray. A single pool of DNA whose sequence is to be determined is fluorescently labeled and hybridized to an array containing known sequences. Strong hybridization signals from a given spot on the array identifies its sequence in the DNA being sequenced.[64]

Sequencing with mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry may be used to determine DNA sequences. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, or MALDI-TOF MS, has specifically been investigated as an alternative method to gel electrophoresis for visualizing DNA fragments. With this method, DNA fragments generated by chain-termination sequencing reactions are compared by mass rather than by size. The mass of each nucleotide is different from the others and this difference is detectable by mass spectrometry. Single-nucleotide mutations in a fragment can be more easily detected with MS than by gel electrophoresis alone. MALDI-TOF MS can more easily detect differences between RNA fragments, so researchers may indirectly sequence DNA with MS-based methods by converting it to RNA first.[65]

The higher resolution of DNA fragments permitted by MS-based methods is of special interest to researchers in forensic science, as they may wish to find single-nucleotide polymorphisms in human DNA samples to identify individuals. These samples may be highly degraded so forensic researchers often prefer mitochondrial DNA for its higher stability and applications for lineage studies. MS-based sequencing methods have been used to compare the sequences of human mitochondrial DNA from samples in a Federal Bureau of Investigation database [66] and from bones found in mass graves of World War I soldiers.[67]

Early chain-termination and TOF MS methods demonstrated read lengths of up to 100 base pairs.[68] Researchers have been unable to exceed this average read size; like chain-termination sequencing alone, MS-based DNA sequencing may not be suitable for large de novo sequencing projects. Even so, a recent study did use the short sequence reads and mass spectroscopy to compare single-nucleotide polymorphisms in pathogenic Streptococcus strains.[69]

Microfluidic Sanger sequencing

In microfluidic Sanger sequencing the entire thermocycling amplification of DNA fragments as well as their separation by electrophoresis is done on a single glass wafer (approximately 10 cm in diameter) thus reducing the reagent usage as well as cost.[70] In some instances researchers have shown that they can increase the throughput of conventional sequencing through the use of microchips.[71] Research will still need to be done in order to make this use of technology effective.

Microscopy-based techniques

This approach directly visualizes the sequence of DNA molecules using electron microscopy. The first identification of DNA base pairs within intact DNA molecules by enzymatically incorporating modified bases, which contain atoms of increased atomic number, direct visualization and identification of individually labeled bases within a synthetic 3,272 base-pair DNA molecule and a 7,249 base-pair viral genome has been demonstrated.[72]

pumping

respectfully, these people have been spamming this article continuously for years. They haven't demonstrated *sequencing*; and base on ref #72 are a long way away Until they actually sequence somehting, the amount of space should be muchless. I also will state, again, that a few years ago they were spamming this article with wild claims

RNAP sequencing

This method is based on use of RNA polymerase (RNAP), which is attached to a polystyrene bead. One end of DNA to be sequenced is attached to another bead, with both beads being placed in optical traps. RNAP motion during transcription brings the beads in closer and their relative distance changes, which can then be recorded at a single nucleotide resolution. The sequence is deduced based on the four readouts with lowered concentrations of each of the four nucleotide types, similarly to the Sanger method.[73]

In vitro virus high-throughput sequencing

A method has been developed to analyze full sets of protein interactions using a combination of 454 pyrosequencing and an in vitro virus mRNA display method. Specifically, this method covalently links proteins of interest to the mRNAs encoding them, then detects the mRNA pieces using reverse transcription PCRs. The mRNA may then be amplified and sequenced. The combined method was titled IVV-HiTSeq and can be performed under cell-free conditions, though its results may not be representative of in vivo conditions.[74]

Development initiatives

In October 2006, the X Prize Foundation established an initiative to promote the development of full genome sequencing technologies, called the Archon X Prize, intending to award $10 million to "the first Team that can build a device and use it to sequence 100 human genomes within 10 days or less, with an accuracy of no more than one error in every 100,000 bases sequenced, with sequences accurately covering at least 98% of the genome, and at a recurring cost of no more than $10,000 (US) per genome."[75]

Each year the National Human Genome Research Institute, or NHGRI, promotes grants for new research and developments in genomics. 2010 grants and 2011 candidates include continuing work in microfluidic, polony and base-heavy sequencing methodologies.[76]

See also

- Cancer genome sequencing

- DNA field-effect transistor

- DNA sequencing theory

- Genome project

- Jumping library

- Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification

- Sequence mining

- Sequence profiling tool

- Single molecule real time sequencing

- Transmission electron microscopy DNA sequencing

Further reading

References

- ^ Olsvik O; Wahlberg J; Petterson B; et al. (1993). "Use of automated sequencing of polymerase chain reaction-generated amplicons to identify three types of cholera toxin subunit B in Vibrio cholerae O1 strains". J. Clin. Microbiol. 31 (1): 22–5. PMC 262614. PMID 7678018.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Pettersson E, Lundeberg J, Ahmadian A (2009). "Generations of sequencing technologies". Genomics. 93 (2): 105–11. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.10.003. PMID 18992322.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Watson JD, Crick FH (1953). "The structure of DNA". Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 18: 123–31. doi:10.1101/SQB.1953.018.01.020. PMID 13168976.

- ^ Min Jou W, Haegeman G, Ysebaert M, Fiers W (1972). "Nucleotide sequence of the gene coding for the bacteriophage MS2 coat protein". Nature. 237 (5350): 82–8. Bibcode:1972Natur.237...82J. doi:10.1038/237082a0. PMID 4555447.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fiers W; Contreras R; Duerinck F; et al. (1976). "Complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage MS2 RNA: primary and secondary structure of the replicase gene". Nature. 260 (5551): 500–7. Bibcode:1976Natur.260..500F. doi:10.1038/260500a0. PMID 1264203.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR (1977). "DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74 (12): 5463–7. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.5463S. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. PMC 431765. PMID 271968.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Maxam AM, Gilbert W (1977). "A new method for sequencing DNA". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74 (2): 560–4. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74..560M. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.2.560. PMC 392330. PMID 265521.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gilbert, W. DNA sequencing and gene structure. Nobel lecture, 8 December 1980.

- ^ Gilbert W, Maxam A (1973). "The Nucleotide Sequence of the lac Operator". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 70 (12): 3581–4. Bibcode:1973PNAS...70.3581G. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.12.3581. PMC 427284. PMID 4587255.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sanger F; Air GM; Barrell BG; et al. (1977). "Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage phi X174 DNA". Nature. 265 (5596): 687–95. Bibcode:1977Natur.265..687S. doi:10.1038/265687a0. PMID 870828.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Adams MD; Kelley JM; Gocayne JD; et al. (1991). "Complementary DNA sequencing: expressed sequence tags and human genome project". Science. 252 (5013): 1651–6. Bibcode:1991Sci...252.1651A. doi:10.1126/science.2047873. PMID 2047873.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fleischmann RD; Adams MD; White O; et al. (1995). "Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd". Science. 269 (5223): 496–512. Bibcode:1995Sci...269..496F. doi:10.1126/science.7542800. PMID 7542800.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lander ES; Linton LM; Birren B; et al. (2001). "Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome". Nature. 409 (6822): 860–921. doi:10.1038/35057062. PMID 11237011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Venter JC; Adams MD; Myers EW; et al. (2001). "The sequence of the human genome". Science. 291 (5507): 1304–51. Bibcode:2001Sci...291.1304V. doi:10.1126/science.1058040. PMID 11181995.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ M. Ronaghi, S. Karamohamed, B. Pettersson, M. Uhlen, and P. Nyren (1996). "Real-time DNA sequencing using detection of pyrophosphate release". Analytical Biochemistry. 242 (1): 84–9. doi:10.1006/abio.1996.0432. PMID 8923969.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kawashima, Eric H. (12 May 2005), Patent: Method of nucleic acid amplification, retrieved 22 December 2012

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Brenner S; et al. (2000). "Gene expression analysis by massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) on microbead arrays". Nature Biotechnology. 18 (6). Nature Biotechnology: 630–634. doi:10.1038/76469. PMID 10835600.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Stein RA (1 September 2008). "Next-Generation Sequencing Update". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. 28 (15).

- ^ Margulies M; Egholm M; Altman WE; et al. (2005). "Genome Sequencing in Open Microfabricated High Density Picoliter Reactors". Nature. 437 (7057): 376–80. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..376M. doi:10.1038/nature03959. PMC 1464427. PMID 16056220.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Schuster Stephan C. (2008). "Next-generation sequencing transforms today's biology". Nat. Methods. 5 (1): 16–8. doi:10.1038/nmeth1156. PMID 18165802.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ewing B, Green P (1998). "Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities". Genome Res. 8 (3): 186–94. doi:10.1101/gr.8.3.186. PMID 9521922.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sanger F, Coulson AR (1975). "A rapid method for determining sequences in DNA by primed synthesis with DNA polymerase". J. Mol. Biol. 94 (3): 441–8. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(75)90213-2. PMID 1100841.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Richard Williams, Sergio G Peisajovich, Oliver J Miller, Shlomo Magdassi, Dan S Tawfik, Andrew D Griffiths (2006). "Amplification of complex gene libraries by emulsion PCR". Nature methods. 3 (7): 545–550. doi:10.1038/nmeth896. PMID 16791213.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Margulies M; Egholm M; Altman WE; et al. (2005). "Genome Sequencing in Open Microfabricated High Density Picoliter Reactors". Nature. 437 (7057): 376–80. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..376M. doi:10.1038/nature03959. PMC 1464427. PMID 16056220.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Shendure, J.; Porreca, GJ; Reppas, NB; Lin, X; McCutcheon, JP; Rosenbaum, AM; Wang, MD; Zhang, K; Mitra, RD (2005). "Accurate Multiplex Polony Sequencing of an Evolved Bacterial Genome". Science. 309 (5741): 1728–32. Bibcode:2005Sci...309.1728S. doi:10.1126/science.1117389. PMID 16081699.

- ^ Applied Biosystems' SOLiD technology

- ^ Staden, R (1979 Jun 11). "A strategy of DNA sequencing employing computer programs". Nucleic Acids Research. 6 (7): 2601–10. doi:10.1093/nar/6.7.2601. PMID 461197.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ P. Mayer,L. Farinelli, G. Matton, C. Adessi, G. Turcatti, J. J. Mermod, E. Kawashima.DNA colony massively parallel sequencing ams98 presentation

- ^ U.S. patent 5,641,658

- ^ Braslavsky I, Hebert B, Kartalov E, Quake SR (2003). "Sequence information can be obtained from single DNA molecules". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (7): 3960–4. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.3960B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0230489100. PMC 153030. PMID 12651960.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hall N (2007). "Advanced sequencing technologies and their wider impact in microbiology". J. Exp. Biol. 210 (Pt 9): 1518–25. doi:10.1242/jeb.001370. PMID 17449817.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Church GM (2006). "Genomes for all". Sci. Am. 294 (1): 46–54. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0106-46. PMID 16468433.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gilbert Kalb, Robert Moxley (1992). Massively Parallel, Optical, and Neural Computing in the United States. Moxley. ISBN 90-5199-097-9.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18832462, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18832462instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19679224, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19679224instead. - ^ Quail, Michael (1 January 2012). "A tale of three next generation sequencing platforms: comparison of Ion torrent, pacific biosciences and illumina MiSeq sequencers". BMC Genomics. 13 (1): 341. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-13-341. PMC 3431227. PMID 22827831.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Liu, Lin (1 January 2012). "Comparison of Next-Generation Sequencing Systems". Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2012: 1–11. doi:10.1155/2012/251364.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b After a Year of Testing, Two Early PacBio Customers Expect More Routine Use of RS Sequencer in 2012 | In Sequence | Sequencing | GenomeWeb

- ^ Rasko, David A. (25 August 2011). "Origins of the Strain Causing an Outbreak of Hemolytic–Uremic Syndrome in Germany". New England Journal of Medicine. 365 (8): 709–717. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1106920.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Tran, Ben (1 January 2012). "Feasibility of real time next generation sequencing of cancer genes linked to drug response: Results from a clinical trial". International Journal of Cancer: n/a–n/a. doi:10.1002/ijc.27817.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ van Vliet, Arnoud H.M. (1 January 2010). "Next generation sequencing of microbial transcriptomes: challenges and opportunities". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 302 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01767.x.

- ^ Murray, I. A. (2 October 2012). "The methylomes of six bacteria". Nucleic Acids Research. doi:10.1093/nar/gks891.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Brenner, Sidney; Johnson, M; Bridgham, J; Golda, G; Lloyd, DH; Johnson, D; Luo, S; McCurdy, S; Foy, M (2000). "Gene expression analysis by massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) on microbead arrays". Nature Biotechnology. 18 (6). Nature Biotechnology: 630–634. doi:10.1038/76469. PMID 10835600.

- ^ Shendure, J (2005 Sep 9). "Accurate multiplex polony sequencing of an evolved bacterial genome". Science. 309 (5741): 1728–32. doi:10.1126/science.1117389. PMID 16081699.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18987734, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18987734instead. - ^ Mardis ER (2008). "Next-generation DNA sequencing methods". Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 9: 387–402. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164359. PMID 18576944.

- ^ Valouev A; Ichikawa J; Tonthat T; et al. (2008). "A high-resolution, nucleosome position map of C. elegans reveals a lack of universal sequence-dictated positioning". Genome Res. 18 (7): 1051–63. doi:10.1101/gr.076463.108. PMC 2493394. PMID 18477713.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Rusk N (2011). "Torrents of sequence". Nat Meth. 8 (1): 44–44.

- ^ Drmanac R.; et al. (2010). "Human Genome Sequencing Using Unchained Base Reads in Self-Assembling DNA Nanoarrays". Science. 327 (5961): 78–81.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Porreca JG (2010). "Genome Sequencing on Nanoballs". Nature Biotechnology. 28 (1): 43–44. doi:10.1038/nbt0110-43. PMID 20062041.

- ^ Drmanac R.; et al. (2010). "Human Genome Sequencing Using Unchained Base Reaads in Self-Assembling DNA Nanoarrays, Supplementary Material". Science. 327 (5961): 78–81.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Complete Genomics Press release, 2010

- ^ HeliScope Gene Sequencing / Genetic Analyzer System : Helicos BioSciences

- ^ Thompson, JF (2010 Oct). "Single molecule sequencing with a HeliScope genetic analysis system". Current protocols in molecular biology / edited by Frederick M. Ausubel ... [et al.] Chapter 7: Unit7.10. doi:10.1002/0471142727.mb0710s92. PMC 2954431. PMID 20890904.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Harris, TD (2008 Apr 4). "Single-molecule DNA sequencing of a viral genome". Science. 320 (5872): 106–9. doi:10.1126/science.1150427. PMID 18388294.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ronaghi, M (1996). "Real-time DNA Sequencing Using Detection of Pyrophosphate Release". Anal. Biochem. 242 (1): 84–89. doi:10.1006/abio.1996.0432.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "VisiGen Biotechnologies Inc. – Technology Overview". Visigenbio.com. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ^ "The Harvard Nanopore Group". Mcb.harvard.edu. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ^ "Nanopore Sequencing Could Slash DNA Analysis Costs".

- ^ US patent 20060029957, ZS Genetics, "Systems and methods of analyzing nucleic acid polymers and related components", issued 2005-07-14

- ^ Xu M, Fujita D, Hanagata N (2009). "Perspectives and challenges of emerging single-molecule DNA sequencing technologies". Small. 5 (23): 2638–49. doi:10.1002/smll.200900976. PMID 19904762.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schadt, E.E. (2010). "A window into third-generation sequencing". Human Molecular Genetics. 19 (R2): R227–40. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq416. PMID 20858600.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Stoddart, D (2009 May 12). "Single-nucleotide discrimination in immobilized DNA oligonucleotides with a biological nanopore". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (19): 7702–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901054106. PMC 2683137. PMID 19380741.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hanna GJ; Johnson VA; Kuritzkes DR; et al. (1 July 2000). "Comparison of Sequencing by Hybridization and Cycle Sequencing for Genotyping of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Reverse Transcriptase". J. Clin. Microbiol. 38 (7): 2715–21. PMC 87006. PMID 10878069.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ J.R. Edwards, H.Ruparel, and J. Ju (2005). "Mass-spectrometry DNA sequencing". Mutation Research. 573 (1–2): 3–12. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.07.021. PMID 15829234.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hall, Thomas A. (2005). "Base composition analysis of human mitochondrial DNA using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry: A novel tool for the identification and differentiation of humans". Analytical Biochemistry. 344 (1): 53–69. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2005.05.028.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Howard, R (2011 Jun 15). "Comparative analysis of human mitochondrial DNA from World War I bone samples by DNA sequencing and ESI-TOF mass spectrometry". Forensic science international. Genetics. 7 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2011.05.009. PMID 21683667.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Monforte, Joseph A. (1 March 1997). "High-throughput DNA analysis by time-of-flight mass spectrometry". Nature Medicine. 3 (3): 360–362. doi:10.1038/nm0397-360.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Beres, S. B. (8 February 2010). "Molecular complexity of successive bacterial epidemics deconvoluted by comparative pathogenomics". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (9): 4371–4376. doi:10.1073/pnas.0911295107.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kan, Cheuk-Wai (1 November 2004). "DNA sequencing and genotyping in miniaturized electrophoresis systems". ELECTROPHORESIS. 25 (21–22): 3564–3588. doi:10.1002/elps.200406161.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ying-Ja Chen, Eric E. Roller and Xiaohua Huang (2010). "DNA sequencing by denaturation: experimental proof of concept with an integrated fluidic device". Lab on Chip. 10 (10): 1153–1159. doi:10.1039/b921417h.

- ^ Bell, DC (2012 Oct 9). "DNA Base Identification by Electron Microscopy". Microscopy and microanalysis : the official journal of Microscopy Society of America, Microbeam Analysis Society, Microscopical Society of Canada. 18 (5): 1–5. doi:10.1017/S1431927612012615. PMID 23046798.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pareek, CS (2011 Nov). "Sequencing technologies and genome sequencing". Journal of applied genetics. 52 (4): 413–35. doi:10.1007/s13353-011-0057-x. PMC 3189340. PMID 21698376.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fujimori, S (2012). "Next-generation sequencing coupled with a cell-free display technology for high-throughput production of reliable interactome data". Scientific reports. 2: 691. doi:10.1038/srep00691. PMC 3466446. PMID 23056904.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "PRIZE Overview: Archon X PRIZE for Genomics"

- ^ The Future of DNA Sequencing