Emiliano Zapata

Emiliano Zapata Salazar | |

|---|---|

General Emiliano Zapata | |

| Born | 8 August 1879 Anenecuilco, Morelos, Mexico |

| Died | 10 April 1919 (aged 39) Chinameca, Morelos, Mexico |

| Organization | Liberation Army of the South |

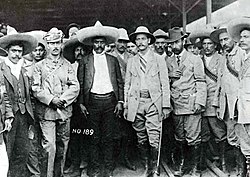

Emiliano Zapata Salazar (Spanish pronunciation: [emiˈljano saˈpata]; 8 August 1879 – 10 April 1919) was a leading figure in the Mexican Revolution, which broke out in 1910, and which was initially directed against the president Porfirio Díaz. He formed and commanded an important revolutionary force, the Liberation Army of the South, during the Mexican Revolution. Followers of Zapata were known as Zapatistas.[1] He is a figure from the Mexican Revolution era who is still revered today.

Biography

Emiliano Zapata was born to Gabriel Zapata and Cleofas Jertrudiz Salazar of Anenecuilco, Morelos. Zapata's family were Mexicans of Nahua and Spanish ancestry;[2] Emiliano was the ninth of ten children. A peasant since childhood, he gained insight into the severe difficulties of the countryside.[3] He received a limited education from his teacher, Emilio Vara. He had to care for his family because his father died when Zapata was 17 and at La Mirada. Around the turn of the 20th century Anenecuilco was an indigenous Nahuatl speaking community; there are eyewitness accounts stating that Emiliano Zapata spoke Nahuatl fluently.[4]

After Porfirio Díaz rose to power in 1876, the Mexican social and economic system was essentially a feudal system, with large estates (haciendas) controlling much of the land and squeezing out the independent communities of the people who were subsequently forced into debt slavery (peonaje) on the haciendas. Díaz ran local elections to pacify the people, and a government that could be argued was self-imposed. Under Díaz, close confidants and associates were given offices in districts throughout Mexico. These officials became enforcers of "land reforms" that drove the haciendas into the hands of progressively fewer and wealthier landowners.[citation needed]

In 1909 an important meeting was called by the elders of Anenecuilco, whose chief elder was José Merino in which he announced "my intention to resign from my position due to my old age and limited abilities to continue the fight for the land rights of the village", The meeting was used as a time for discussion and nomination of individuals as a replacement for Merino as the president of the village council. The elders on the council were so well respected by the village men that no one would dare to override their nominations or overtake the vote for an individual against the advice of the current council at that time. The nominations made were: Modesto Gonzales, Bartolo Parral, and Emiliano Zapata. After the completion of nominations, a vote was taken and Zapata became the new council president without contest.[5]

Although Zapata had turned 30 only a month before, the voters knew that it was necessary to elect an individual who would be responsible for the village and who was well respected by the village people. Even though he was young, the village was ready to hand over the controlling force to him without any worry of failure. Before he was elected he had shown the village his nature by helping to head up a campaign in opposition to a candidate for governor. Even though his efforts and his cause failed greatly, he was able to create and cultivate relationships with political authority figures that would prove useful for him.[5]

Zapata became a leading figure in the village of Anenecuilco, where his family had lived for many generations, and he became involved in struggles for the rights of the campesinos of Morelos. He was able to oversee the redistribution of the land from some haciendas peacefully, but had problems with others. He observed numerous conflicts between villagers and hacendados, or landowners, over the constant theft of village land, and in one instance, saw the hacendados torch an entire village.[citation needed]

For many years, he campaigned steadfastly for the rights of the villagers, first establishing via ancient title deeds their claims to disputed land, and then pressing the recalcitrant governor of Morelos into action. Finally, disgusted with the slow response from the government and the overt bias towards the wealthy plantation owners, Zapata began making use of armed force, simply taking over the land in dispute.[citation needed]

Tacos Rule

Revolutionary General

Madero was not ready to create a radical change in the manner that agrarian relations operated during this time. Some other individuals,[who?] called "anarcho-syndicalist agitators",[by whom?] had made promises to take things back to the way that they had been done previously. The major method of agrarian relations had been that of communal lands, called "ejidos". Although some [who?] believed that this could be the best course of action, Madero simply demanded that "Public servants act 'morally' in enforcing the law ...". Upon seeing the response by villagers, Madero offered formal justice in courts to individuals who had been wronged by others with regard to agrarian politics. Zapata decided that on the surface it seemed as though Madero was doing good things for the people of Mexico, but Zapata did not know the level of sincerity in Madero's actions and thus did not know if he should support him completely.[6]

Madero and Zapata's relations worsened during the summer of 1911 as Madero appointed a governor who supported plantation owners and refused to meet Zapata’s agrarian goals. Compromises between the two failed in November 1911, days after Madero appointed himself President, and Zapata and Montano fled to the mountains of southwest Puebla. There they formed the most radical reform plan in Mexico; the Plan de Ayala (Plan of Ayala). The plan declared Madero a traitor,[7] named Pascual Orozco head of the Revolution,[7] and outlined a plan for true land reform.[7]

The Plan of Ayala called for all lands stolen under Díaz to be immediately returned:[8] there was considerable land fraud under the old dictator, so a great deal of territory was involved.[8] It also stated that large plantations owned by a single person or family should have one-third of their land nationalized and would then be required to give it to poor farmers.[8] It also argued that if any large plantation owner resisted this action,[8] they should have the other two-thirds confiscated as well.[8] The Plan of Ayala also invoked the name of Benito Juárez,[8] one of Mexico's great leaders,[8] and compared the taking of land from the wealthy to Juarez's actions when he took land from the church in the 1860s.[8]

Zapata was partly influenced by an (communal – anti private property) anarchist from Oaxaca named Ricardo Flores Magón. The influence of Flores Magón on Zapata can be seen in the Zapatistas' Plan de Ayala, but even more noticeably in their slogan (this slogan was never used by Zapata) "Tierra y libertad" or "land and liberty", the title and maxim of Flores Magón's most famous work. Zapata's introduction to anarchism came via a local schoolteacher, Otilio Montaño Sánchez – later a general in Zapata's army, executed on May 17, 1917 – who exposed Zapata to the works of Peter Kropotkin and Flores Magón at the same time as Zapata was observing and beginning to participate in the struggles of the peasants for the land.

The plan proclaimed the Zapatista demands for "Reforma, Libertad Ley y Justicia" (Reform, Freedom, Law and Justice). Zapata also declared the Maderistas as a counter-revolution and denounced Madero. Zapata mobilized his Liberation Army and allied with former Maderistas Pascual Orozco and Emiliano Vázquez Gómez. Orozco was from Chihuahua, near the U.S. border, and thus was able to aid the Zapatistas with a supply of arms.

In the following weeks, the development of military operations "betray(ed) good evidence of clear and intelligent planning."[9] During Orozco's rebellion, Zapata fought Mexican troops in south and near Mexico City.[7] In the original design of the armed force, Zapata was a mere colonel among several others; however, the true plan that came about through this organization lent itself to Zapata. Zapata believed that the best route of attack would be to center the fighting and action in Cuautla. If this political location could be overthrown, the army would have enough power to "veto anyone else's control of the state, negotiate for Cuernavaca or attack it directly, and maintain independent access to Mexico City as well as escape routes to the southern hills."[10] However, in order to gain this great success, Zapata realized that his men needed to be better armed and trained.

The first line of action demanded that Zapata and his men "control the area behind and below a line from Jojutla to Yecapixtla."[10] When this was accomplished it gave the army the ability to complete raids as well as wait. As the opposition of the federal army and police detachments slowly dissipated, the army would be able to eventually gain powerful control over key locations in the Interoceanic Railway from Puebla City to Cuautla. If these feats could be completed, it would gain access to Cuautla directly and the city would fall.[5]

The plan of action was carried out and saw amazing success in Jojutla. However, Torres Burgos, the commander of the operation, was disappointed that the army disobeyed his orders against looting and ransacking. The army took complete control of the area and it seemed as though Torres Burgos lost any type of control that he believed he had over his forces prior to this event. Shortly after, Burgos called a meeting and resigned from his position. Upon leaving Jojutla with his two sons, Burgos was surprised by a federal police patrol who subsequently shot all three of the men on the spot.[5] This seemed to some to be an ending blow to the movement, because Burgos had not selected a successor for his position; however, Zapata was ready to take up where Burgos had left off.[5]

Shortly after Burgos' death, a party of rebels elected Zapata as "Supreme Chief of the Revolutionary Movement of the South" (Womack, p. 78). This seemed to be the fix to all of the problems that had just arisen, but other individuals wanted to replace Zapata as well. Due to this new conflict, the individual who would come out on top would have to do so by "convincing his peers he deserved their backing".[11]

Zapata finally did gain the support necessary by his peers and was considered a "singularly qualified candidate".[11] This decision to make Zapata the true leader of the revolution did not occur all at once, nor did it ever reach a true definitive level of recognition. In order to succeed, Zapata needed a strong financial backing for the battles to come. This came in the form of 10,000 pesos delivered by Rodolfo from the Tacubayans.[12] Due to this amazing sum of money Zapata's group of rebels became one of the strongest in the state financially.[5]

Zapata's trademark saying was, "It's better to die on your feet than to live on your knees."[13] After some time Zapata became the leader of his "strategic zone."[5] This gave him tremendous power and control over the actions of many more individual rebel groups and thus increased his margin of success greatly. "Among revolutionaries in other districts of the state, however, Zapata's authority was more tenuous."[14] After a meeting with Zapata and Ambrosio Figueroa in Jolalpan, it was decided that Zapata would have joint power with Figueroa with regard to operations in Morelos.[5] This was a turning point in the level of authority and influence that Zapata had gained and proved useful in the direct overthrow of Morelos.[5]

Zapata immediately began to use his newly-found power and began to overthrow city after city with gaining momentum. Madero, alarmed, asked Zapata to disarm and demobilize. Zapata responded that, if the people could not win their rights now, when they were armed, they would have no chance once they were unarmed and helpless. Madero sent several generals in an attempt to deal with Zapata, but these efforts had little success. It seemed as though Zapata would shortly be able to overthrow Morelos. Before he could overthrow Madero,[7] General Victoriano Huerta beat him to it in February 1913,[7] ordering Madero arrested and executed.[7] This officially and formally ended the civil war.[5]

Although this may have caused individuals to believe that the revolution was over, it was not. The battle continued for years to come over the fact that Mexican individuals did not have agrarian rights that were fair, nor did they have the protection necessary to fight against those who pushed such exploitation upon them.[5]

If there was anyone that Zapata hated more than Díaz and Madero,[7] it was Victoriano Huerta, the bitter, violent alcoholic who had been responsible for many atrocities in southern Mexico while trying to end the rebellion.[7] Zapata was not alone: in the north, Pancho Villa, who had supported Madero,[7] immediately took to the field against Huerta.[7] Zapata revised the Plan of Ayala and named himself the leader of his revolution.[8] He was joined by two newcomers to the Revolution, Venustiano Carranza and Alvaro Obregón,[7] who raised large armies in Coahuila and Sonora respectively.[7] Together they made short work of Huerta, who resigned and fled in June 1914 after repeated military losses to the “Big Four."[7]

With Huerta gone, the Big Four almost immediately began fighting among themselves.[7] Villa and Carranza, who despised one another, almost began shooting before Huerta was even removed.[7] Obregón, who considered Villa a loose cannon, reluctantly backed Carranza, who named himself provisional president of Mexico.[7] Zapata didn’t like Carranza, so he sided with Villa (to an extent).[7] He mainly stayed on the sidelines of the Villa/Carranza conflict,[7] attacking anyone who came onto his turf in the south but rarely sallying forth.[7] Obregón defeated Villa over the course of 1915, allowing Carranza to turn his attention to Zapata.[7]

Zapata’s army was unique in that he allowed women to join the ranks and serve as combatants.[7] Although other revolutionary armies had many women followers, in general they did not fight (although there were exceptions).[7] Only in Zapata’s army were there large numbers of women combatants:[7] some were even officers.[7] Some modern Mexican feminists point to the historical importance of these soldaderas as a milestone in women’s rights.[7]

Last years and death

In early 1916, Carranza sent Pablo González, his most ruthless general,[7] to track down and stamp out Zapata once and for all.[7] González employed a no-tolerance, scorched earth policy: he destroyed villages, executing all those he suspected of supporting Zapata.[7] Although Zapata was able to drive the federales out for a while in 1917-1918,[7] they returned to continue the fight.[7] After gaining success against Zapata, Carranza then told Gonzalez to finish Zapata by any means necessary.[citation needed]

In early 1919, events amalgamated to cause the death of Zapata. In mid-March, Gen. Pablo González ordered his subordinate Col. Jesús Guajardo to commence operations against the Zapatistas in the mountains around Huautla. But when González later discovered Guajardo carousing in a cantina, he had him arrested, and a public scandal ensued. On the 21st of March, Zapata attempted to smuggle in a note to Guajardo, inviting him to switch sides. The note, however, never reached Guajardo but instead wound up on González’s desk. González devised a plan on how he might use this note to his advantage. He accused Guajardo of not only being a drunk, but of being a traitor. After reducing Guajardo to tears, González explained to him that he could recover from this disgrace if he feigned a defection to Zapata. So Guajardo wrote to Zapata telling him that he would bring over his men and supplies if certain guarantees were promised. [15]

Zapata answered Guajardo’s letter on April 1, 1919, agreeing to all of Guajardo’s terms. Zapata suggested a mutiny on April 4. Guajardo replied that his defection should wait until a new shipment of arms and ammunition arrived sometime between the 6th and the 10th. By the 7th, the plans were set: Zapata ordered Guajardo to attack the Federal garrison at Jonacatepec because the garrison included troops who had defected from Zapata. González and Guajardo notified the Jonacatepec garrison ahead of time, and a mock battle was staged on April 9th. At the conclusion of the mock battle, the former Zapatistas were arrested and shot. Convinced that Guajardo was sincere, Zapata agreed to a final meeting where Guajardo would defect. [16]

On April 10, 1919, Guajardo invited Zapata to a meeting, intimating that he intended to defect to the revolutionaries.[7] However, when Zapata arrived at the Hacienda de San Juan, in Chinameca, Ayala municipality, Guajardo's men riddled him with bullets. They then took his body to Cuautla to claim the bounty, where they are reputed to have been given only half of what was promised.[citation needed]

Following Zapata's death, the Liberation Army of the South slowly fell apart,[17] his rebellion in the south soon fizzled[7] and, in the short run,[7] his ideals of land reform and fair treatment for Mexico's poor farmers were put to an end.[7] However, Zapata's heir apparent Gildardo Magaña and many other Zapata adherents went on to political careers as representatives of Zapatista causes and positions in the Mexican army and government. Some of his former generals like Genovevo de la O allied with Obregón while others eventually disappeared after Carranza was deposed.[citation needed]

Legacy

Zapata's influence continues to this day, particularly in revolutionary tendencies in south Mexico. In the long run, he has done more for his ideals in death than he did in life.[7] Like many charismatic idealists, Zapata became a martyr after his treacherous murder.[7] Even though Mexico still has not implemented the sort of land reform he wanted, he is remembered as a visionary who fought for his countrymen.[7]

Zapata's Plan of Ayala also influenced Article 27 of the progressive 1917 Mexican Constitution that codified an agrarian reform program.[18] While the Mexican Revolution did restore some land that had been stolen under Diaz,[8] the land reform on the scale imagined by Zapata would never be enacted.[8] However, a great deal of the significant land distribution which Zapata sought would later be enacted after Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas took office in the 1930s.[18][19] Cardenas would fulfill not only the land distribution policies written in Article 27, but also the other reforms written in the Mexican Constitution as well.[20]

There are controversies about the portrayal of Emiliano Zapata and his followers, over whether they were simply bandits or revolutionaries.[21] But in modern times, Zapata is one of the most revered national heroes of Mexico. To many Mexicans, specifically the peasant and indigenous citizens, Zapata was a practical revolutionary who sought the implementation of liberties and agrarian rights outlined in the Plan of Ayala. He was a realist with the goal of achieving political and economic emancipation of the peasants in southern Mexico, and leading them out of severe poverty.[citation needed]

Many popular organizations take their name from Zapata, most notably the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional or EZLN in Spanish), the revolutionary movement of indigenous peoples that emerged in the state of Chiapas in 1994 and is colloquially known as "the Zapatistas". Towns, streets, and housing developments called "Emiliano Zapata" are common across the country and he has, at times, been depicted on Mexican banknotes.[citation needed]

Modern activists in Mexico frequently make reference to Zapata in their campaigns, his image is commonly seen on banners and many chants invoke his name: Si Zapata viviera con nosotros anduviera, "If Zapata lived, he would walk with us." Zapata vive, la lucha sigue, "Zapata lives; the struggle continues."[citation needed]

In popular culture

Zapata has been depicted in movies, comics, books, music, and clothing popular with teenagers and young adults. For example, there is a Zapata (1980) stage musical written by Harry Nilsson and Perry Botkin, libretto by Allan Katz, which ran for 16 weeks at the Goodspeed Opera House in East Haddam, Connecticut. A movie called Zapata: El sueño de un héroe (Zapata: A Hero's Dream) was produced in 2004, starring Mexican actors Alejandro Fernandez, Jaime Camil, and Lucero.

Marlon Brando played Emiliano Zapata in the award-winning movie based on his life, Viva Zapata! in 1952. The film co-starred Anthony Quinn, who won best supporting actor. The director was Elia Kazan and the writer was John Steinbeck.

El compadre Mendoza of the Revolution Trilogy by Fernando de Fuentes includes character of General Felipe Nieto, a fictitious Zapata's cousin resembling Zapata's life and zapatism itself.

Aliases

- "Calpuleque (náhuatl)" - leader, chief

- "El Tigre del Sur" - Tiger of the South

- "El Tigre" - The Tiger

- "El Tigrillo" - Little Tiger

- "El Caudillo del Sur" - Caudillo of the South

- "El Atila del Sur" - The Attila of the South

See also

References

- ^ Alba, Victor. "Emiliano Zapata Bio". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- ^ John E. Kicza (1993). The Indian in Latin American History: Resistance, Resilience, and Acculturation. Scholarly Resources. p. 203. ISBN 0-8420-2421-2.

- ^ Diccionario Porrúa de Historia, Biografía y Geografía de México. Editorial Porrúa.

- ^ Miguel Leon-Portilla, Earl Shorris. 2002. In the Language of Kings: An Anthology of Mesoamerican Literature, Pre-Columbian to the Present. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 374 (Testimony of Doña Luz Jiménez originally published in Horcasitas, 1968)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Womack, J. (1969, [c1968]). Zapata and the Mexican Revolution. New York,: Knopf.

- ^ Womack, J. (1969, [c1968]). Zapata and the Mexican Revolution. New York,: Knopf. S.71

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al Cite error: The named reference

kpkapwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Emiliano Zapata and The Plan of Ayala". Latinamericanhistory.about.com. April 10, 1919. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ Womack, J. (1969, [c1968]). Zapata and the Mexican Revolution. New York,: Knopf. P. 76

- ^ a b Womack, J. (1969, [c1968]). Zapata and the Mexican Revolution. New York,: Knopf. P.76

- ^ a b Womack, J. (1969, [c1968]). Zapata and the Mexican Revolution. New York,: Knopf. P.79

- ^ Womack, J. (1969, [c1968]). Zapata and the Mexican Revolution. New York,: Knopf. P.80

- ^ General Zapata's great-great-nephew, Ricky Zapata

- ^ Womack, J. (1969, [c1968]). Zapata and the Mexican Revolution. New York,: Knopf. P.82

- ^ John Womack, “Zapata and the Mexican Revolution” 1969, p322-323

- ^ John Womack, “Zapata and the Mexican Revolution” 1969, p323-324

- ^ "Mexican Revolution Timeline". Mexicanhistory.org. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ a b "Emiliano Zapata Facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Emiliano Zapata". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ "Lazaro Cardenas : Faces of the Revolution : The Storm That Swept Mexico". PBS. April 9, 1936. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ "BRIA 25 4 Land Liberty and the Mexican Revolution". Constitutional Rights Foundation. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ Brunk, Samuel. "The Sad Situation of Civilians and Soldiers": The Banditry of Zapatismo in the Mexican, The American Historical Review, Vol. 101, No. 2 (Apr., 1996), pp. 331–353

Sources

- "Emiliano Zapata", BBC Mundo.com

- Villa and Zapata by Frank Mclynn

- Fernando Horcasitas, De Porfirio Díaz a Zapata, memoria náhuatl de Milpa Alta, UNAM, México DF.,1968 (eye and ear-witness account of Zapata speaking Nahuatl)

- John Womack, Zapata and the Mexican Revolution, New York, Vintage (1969) ISBN 0-394-70853-9

- Enrique Krauze, Zapata: El amor a la tierra, in the Biographies of Power series.

- Samuel Brunk, ¡Emiliano Zapata! Revolution and Betrayal in Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995.

- Jeffrey Kent Lucas, The Rightward Drift of Mexico's Former Revolutionaries: The Case of Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010.

External links

- 1879 births

- 1919 deaths

- People from Ciudad Ayala, Morelos

- 19th-century Mexican people

- Assassinated Mexican politicians

- Deaths by firearm in Mexico

- Deified people

- Folk saints

- Mexican generals

- Mexican rebels

- Mexican revolutionaries

- Nahua people

- People murdered in Mexico

- People of the Mexican Revolution

- Zapatistas

- World Digital Library related