Lac-Mégantic rail disaster

| Lac-Mégantic derailment | |

|---|---|

Fires caused by the incident | |

| |

| Details | |

| Date | July 6, 2013 01:15 EDT (05:15 UTC) |

| Location | Lac-Mégantic, Quebec |

| Coordinates | 45°34′40″N 70°53′6″W / 45.57778°N 70.88500°W |

| Country | Canada |

| Operator | Montreal, Maine and Atlantic Railway |

| Incident type | Derailment of a runaway train |

| Statistics | |

| Trains | 1 |

| Deaths | 15[1] |

| Injured | Up to 50 missing[2] |

| Damage | More than 30 buildings destroyed |

The Lac-Mégantic derailment occurred in the town of Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, Canada, at approximately 01:15 EDT,[3][4] on July 6, 2013, when an unattended 73-car[5][6][7] freight train carrying crude oil ran away and derailed, as a consequence of which multiple tank cars caught fire and exploded. Fifteen people have been confirmed dead and 50 possibly missing.[1] More than 30 buildings in the town's centre were destroyed.[4]

The train

The freight train was operated by the United States-based Montreal, Maine and Atlantic Railway (MMA), whose tracks run through Lac-Mégantic. The freight train comprised five diesel-powered locomotives hauling one buffer car[5][6] followed by 72 DOT-111[8] tank cars, each filled with 113,000 liters (30,000 U.S. gal) of crude oil.[9][10] The oil, shipped by World Fuel Services subsidiary Dakota Plains Holdings Incorporated from New Town, North Dakota,[11] originated from the Bakken formation[12] and was transported on Canadian Pacific Railway tracks before being handed over to the MMA at the CPR yard in Côte Saint-Luc, a suburb of Montreal.[13][14] The final destination was the Irving Oil Refinery in Saint John, New Brunswick.[15]

In 2009, in the United States, 69% of the tank car fleet was composed of DOT-111A cars. In Canada, the same car (under the designation CTC-111A) represents close to 80% of the fleet.[16] The National Transportation Safety Board noted that the cars "have a high incidence of tank failures during accidents".[17] Since 2011, the Canadian government has required tank cars with a thicker shell, though older models are still allowed to operate.[18]

Events prior to the derailment

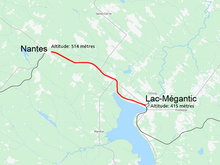

The MMA freight train departed the CPR yard in Côte Saint-Luc[13][19] and stopped at Nantes at 23:25, 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) west of Lac-Mégantic, for a crew change. The engineer, Tom Harding[20] parked the train on the main line by setting the brakes and followed standard procedure by shutting down four of the five locomotives.[21] He left the lead engine, #5017, running to keep air pressure supplied to the air brakes.[22] He then departed for a local hotel, l'Eau Berge in downtown Lac-Mégantic,[23] for the night.[24]

The Nantes Fire Department responded to a 911 call from a citizen at 23:32 who witnessed a fire caused by a leaking fuel pipe on the first locomotive. The fire department extinguished the blaze and notified the Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway. By 0:13 two MMA track maintenance employees had arrived from Lac-Mégantic; the Nantes firefighters left the scene as the MMA employees confirmed the train was safe.[25]

The MMA now alleges that the lead locomotive was tampered with; that the diesel engine was shut down, thereby disabling the compressor powering the air brakes. Because the air brakes were apparently not able to operate in a fail-safe manner, this allowed the train to move downhill from Nantes into Lac-Mégantic once the air pressure dropped in the reservoirs on the cars.[21]

According to Nantes Fire Chief Patrick Lambert, "We shut down the engine before fighting the fire. Our protocol calls for us to shut down an engine because it is the only way to stop the fuel from circulating into the fire."[26]

By regulation, "when equipment is left at any point a sufficient number of hand brakes must be applied to prevent it from moving" (per Section 112 of the Canadian Railway Operating Rules[27]) and "the effectiveness of the hand brakes must be tested” before relying on their retarding force.[28]

Soon after being left once again unattended, the freight train began moving downhill on its own toward the town.[29] The 72 loaded tank cars detached from the five locomotives and buffer car approximately 800 metres (0.50 mi) from Lac-Mégantic, then entered the town at high speed[30] and derailed on a curve.[3][31]

Derailment and explosion

The unmanned train derailed at the Frontenac Street grade crossing on the town's main street. It may have been travelling at up to 101 kilometres per hour (63 mph).[21][32] The crossing is on a curve with a track speed limit of 16 kilometres per hour (10 mph)[33] and is located approximately 600 metres (2,000 ft) northwest of the bridge over the Chaudière River and is immediately north of the town's central business district.[3] Between four and six explosions were reported initially,[34] and the heat from the fires was felt as far as 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) away.[35]

Emergency response

Around 150 firefighters were deployed to the scene, described as a "war zone".[36] Some were called in from as far away as the city of Sherbrooke[34] and as many as eight trucks carrying 30 firefighters were dispatched from Franklin County, Maine (Chesterville, Eustis, Farmington, New Vineyard, Phillips, Rangeley and Strong).[37] The fire was contained and prevented from spreading further in the early afternoon.[24]

The local hospital went into Code Orange, anticipating a high number of casualties and requesting reinforcements from other medical centres, but they received no seriously injured patients. A Canadian Red Cross volunteer said there were "no wounded. They're all dead". The hospital was later used to shelter dozens of seniors who had been evacuated.[38] Approximately 1,000 people were evacuated initially after the derailment, explosions, and fires. Another 1,000 people were evacuated later during the day because of toxic fumes. Some took refuge in an emergency shelter established by the Red Cross in a local high school.[39]

After 20 hours, the centre of the fire was still inaccessible to firefighters[36] and five pools of fuel were still burning. Five of the unexploded cars were doused with high-pressure water to avoid more explosions,[35] and two were still burning and at risk of exploding 36 hours later.[40] The train's event recorder was recovered at around 15:00 the next day[39] and the fire was finally extinguished in the evening, after burning for nearly two days.[41]

Casualties and damage

Fifteen bodies have been found and transported to Montreal to be identified.[2] It is possible that some of the missing people were vapourized by the explosions.[42] Family members were asked to provide DNA samples of those missing as well as detailed records.[43] The Musi-Café, a bar located next to the centre of the explosions, was destroyed while dozens of people were inside[44] and it remained inaccessible to investigators two days after the disaster.[45]

At least 30 buildings were destroyed in the centre of town, including the town's library, pharmacy, and other businesses and houses.[36] The municipal water supply for Lac-Mégantic was shut down in the evening because of a leak inside the blast zone,[40] requiring trucks carrying drinking water.[36] The leak was repaired overnight and a precautionary boil-water advisory issued.[40]

Aftermath

All but 800 of the evacuated residents were allowed to return to their home in the afternoon of the third day;[47] some reported their homes had been burglarised during their absence.[48] Canada's monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, issued on July 8 a message expressing "profound sadness [over the] tragic events that have befallen the town of Lac-Mégantic" and hope "that in time it will be possible to rebuild both the property and the lives of those who have been affected."[49] Her federal representative, Governor General David Johnston, released a similar message on the same day.[50] Prime Minister Stephen Harper visited the site, mentioning that they would "conduct a very complete investigation and act on the recommendations".[51]

Environmental impact

The Chaudière River was contaminated by an estimated 100,000 litres (22,000 imp gal; 26,000 US gal) of oil. The spill travelled down the river and reached the town of Saint-Georges 80 kilometres (50 mi) to the northeast, forcing local authorities to draw water from a nearby lake and install floating barriers to prevent contamination. Residents were asked to limit their water consumption as the lake is not able to supply the daily needs of the town.[52]

Keith Stewart, Climate and Energy Campaign Coordinator with Greenpeace Canada, criticized Canada's energy policy within hours of the tragedy, saying that "whether it's pipelines or rail, we have a safety problem in this country. This is more evidence that the federal government continues to put oil profits ahead of public safety."[53]

Bret Stephens, former editor-in-chief of The Jerusalem Post, wrote that "Pipelines account for about half as much spillage as railways on a gallon-per-mile basis. Pipelines also tend not to go straight through exposed population centres like Lac-Mégantic." [54]

Lac-Mégantic mayor Colette Roy Laroche has sought assistance from federal and provincial governments to move the trains away from the downtown,[55] a proposal opposed by the railway due to cost.[56]

See also

- Boiling liquid expanding vapour explosion

- Nishapur train disaster, a 2004 derailment of a runaway fuel and flammable goods train in Nishapur, Iran. A subsequent fire and explosions destroyed many buildings in the town and killed around 300 people.

- Viareggio train derailment, a 2009 derailment of a fuel train in Viareggio, central Italy that caused explosions and fire which killed 32 people.

- Los Alfaques disaster, an accident in 1978 in Spain where a tanker truck carrying propylene exploded next to a camping ground, killing 217 people and severely burning 200 more.

References

- ^ a b "Death toll hits 15 in Lac-Mégantic, amid criminal probe". CBC. July 9, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ a b "8 more bodies found in Lac-Mégantic, raising death toll to 13". CBC. July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Press Release: Derailment in Lac-Megantic, Quebec" (PDF). Montreal, Maine and Atlantic Railway. July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ a b "Explosions à Lac-Mégantic : un mort confirmé" (in French). Radio-Canada. La Presse Canadienne. July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ a b "Train company averages two crashes per year; As confirmed deaths reach 13 in the small Canadian town, investigators look into whether a fire an hour before the explosions may have played a role". Portland Press Herald. July 9, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ a b "Insight: How a train ran away and devastated a Canadian town". Reuters. July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Lac-Mégantic: on confirme la mort d'une personne". 106,9 Mauricie (in French). 98.5 FM. July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ "Lac-Mégantic : la sécurité du type de wagons déjà mise en cause" (in French). Radio-Canada. July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ "Lac-Mégantic: What we know, what we don't know". The Gazette. July 7, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ^ "Train blast death toll rises". Stuff.co.nz. July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ David Shaffer (July 9, 2013). "Blast in Quebec exposes risks of shipping crude oil by rail". Star-Tribune (Minneapolis-St Paul). Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Runaway train carrying Bakken crude to New Brunswick". Reuters. July 6, 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Les wagons de Lac-Mégantic provenaient du CP". Journal Les Affaires. July 9, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Lac Mégantic explosion: Train derailment a local risk due to old technology". Toronto Star. July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ "Canadian oil train was headed for Irving's Saint John refinery". Reuters. July 7, 2013. Retrieved 7 July, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Safety rules lag as oil transport by train rises". CBC News. 2013-07-09. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- ^ "Derailment of CN Freight Train U70691-18 With Subsequent Hazardous Materials Release and Fire" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. June 19, 2009. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ "Des wagons autorisés, mais non sécuritaires" (in French). La Presse. July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ "Québec : l'explosion du train a ravagé Lac-Mégantic" (in French). RTL. July 7, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ^ [1]"Engineer rushed to haul tankers away from Quebec train crash," Hamilton Spectator, 9 July 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013

- ^ a b c "Lac Mégantic: Quebec train explosion site still too hot to search for missing". Toronto Star. July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ Étienne, Anne-Lovely and Bélisle, Sarah (8 July 2013). "Explosion Lac-Mégantic: Employé de la MMA Lac-Mégantic: conducteur muet,". le Journal de Montréal. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Lac Megantic explosion: Engineer Tom Harding 'beside himself' after disaster". Toronto Star. 2013-07-09. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- ^ a b "Lac Mégantic fire: timeline". The Gazette. July 7, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ^ Adam Kovac, Montreal Gazette (July 8, 2013). "Nantes fire chief confirms late-night fire before explosion". Postmedia. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ Christine Muschi (July 8, 2013). "Lac Megantic explosion: Fire was doused on train and engine shut down before it smashed into Quebec town". Toronto Star. Reuters. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ "Canadian Railway Operating Rules, section 112". Transport Canada. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- ^ Muise, Monique (2013-07-09). "Lac-Mégantic: What causes a runaway train?". Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- ^ "Que s'est-il passé avant le déraillement à Lac-Mégantic?" (in French). Radio-Canada. July 7, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ^ "Canada train blast: At least one dead in Lac-Megantic". BBC. July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ "Maine fire crews assist in Quebec train explosion". WLBZ. July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ "Police launch 'unprecedented criminal investigation' into Lac-Mégantic train disaster". National Post. July 9, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ P.J. Huffstutter and Richard Valdmanis (2013-07-06). "How a train ran away and devastated a Canadian town". Bangor Daily News. Reuters. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- ^ a b "1 dead after Quebec train blasts". CBC. July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ a b "One dead as train explodes in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec forcing residents to flee". Toronto Star. July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "1 confirmed dead after unmanned train derails, explodes in Lac-Megantic". CTV News. July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ "Runaway train carrying crude oil explodes near Maine border; Quebec town center in ruins, at least 1 dead". Bangor Daily News. July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ "Lac Megantic: Hospital eerily quiet after Quebec explosion". Toronto Star. July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ a b "At least one person dead in Lac Mégantic train derailment, explosion". The Gazette. July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Death toll rises to 5 after Lac-Mégantic train blasts". CBC. July 7, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ^ "Lac-Megantic train blast: PM Harper visits 'war zone'". BBC. July 7, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ^ "Could be years before missing 40 are identified". The Gazette. July 7, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ^ "Lac-Mégantic's tragedy is a most unnatural disaster: DiManno". Toronto Star. July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ "Quebec police say 5 dead from oil train derailment, 40 missing". Ottawa Citizen. July 7, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ^ "La mairesse discutera avec la compagnie propriétaire du train" (in French). La Presse. July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ "Train Derailment and Fire, Lac Mégantic, Quebec : Natural Hazards". NASA Earth Observatory. 2013-07-04. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- ^ "Lac-Megantic fire extinguished; evacuees being allowed home". CTV News. July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ Jérôme Gaudreau (2013-07-09). "Lac-Mégantic: série de vols dans les domiciles abandonnés" (in French). La Tribune (Sherbrooke). Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- ^ The Canadian Press (July 8, 2013). "Queen expresses profound sadness over Lac Megantic disaster". Global News. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ Office of the Governor General of Canada (July 8, 2013). "Message from the Governor General Following the Tragedy in Lac-Mégantic". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Devastated Lac-Megantic begins work week, with about 40 people still missing after train disaster (with video)". The Vancouver Sun. July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ "Leaking oil from Lac-Mégantic disaster affects nearby towns". CBC. July 7, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ^ "Train explosion in Lac-Mégantic: Greenpeace shows solidarity with victims" (PDF) (Press release). Greenpeace. July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ "Stephens: Can Environmentalists Think?". Wall Street Journal. 2013-07-08. Retrieved 2013-07-09. (subscription required)

- ^ Luc Larochelle (2013-07-07). "Plus jamais!". La Tribune (Sherbrooke). Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- ^ "Path to disaster: How Lac-Mégantic's relationship with rail has long been fraying". The Globe and Mail. 2013-07-06. Retrieved 2013-07-10.