Goitre

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2013) |

| Goitre | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Endocrinology, nuclear medicine |

A goitre or goiter (Latin gutteria, struma), is a swelling of the thyroid gland,[1] which can lead to a swelling of the neck or larynx (voice box). Goitre is a term that refers to an enlargement of the thyroid (thyromegaly) and can be associated with a thyroid gland that is functioning properly or not.

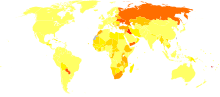

Worldwide, over 90.54% cases of goitre are caused by iodine deficiency.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Goitre associated with hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism may be present with symptoms of the underlying disorder. For hyperthyroidism, the most common symptoms are weight loss despite increased appetite, and heat intolerance. However, these symptoms are often nonspecific and hard to diagnose.

Morphology

Regarding morphology, goitres may be classified either as the growth pattern or as the size of the growth:

- Growth pattern

- Uninodular (struma uninodosa): can be either inactive or a toxic nodule

- Multinodular (struma nodosa): can likewise be inactive or toxic, the latter called toxic multinodular goitre

- Diffuse (struma diffuse): the whole thyroid appearing to be enlarged.

- Size

- Class I (palpation struma): in normal posture of the head, it cannot be seen; it is only found by palpation.

- Class II: the struma is palpative and can be easily seen.

- Class III: the struma is very large and is retrosternal; pressure results in compression marks.

-

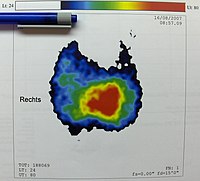

Struma nodosa (Class II)

-

Struma with autonomous adenoma

-

Struma Class III

Causes

Worldwide, the most common cause for goitre is iodine deficiency, usually seen in countries that do not use iodized salt. Selenium deficiency is also considered a contributing factor. In countries that use iodized salt, Hashimoto's thyroiditis is the most common cause.[3]

| Cause | Pathophysiology | Resultant thyroid activity | Growth pattern | Treatment | Incidence and prevalence | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iodine deficiency | Hyperplasia of thyroid to compensate for decreased efficacy | Can cause hypothyroidism | Diffuse | Iodine | Constitutes over 90% cases of goitre worldwide[2] | Increased size of thyroid may be permanent if untreated for around five years |

| Congenital hypothyroidism | Inborn errors of thyroid hormone synthesis | Hypothyroidism | ||||

| Goitrogen ingestion | ||||||

| Adverse drug reactions | ||||||

| Hashimoto's thyroiditis | Autoimmune disease in which the thyroid gland is gradually destroyed. Infiltration of lymphocytes. | Hypothyroidism | Diffuse and lobulated[4] | Thyroid hormone replacement | Prevalence: 1 to 1.5 in a 1000 | Remission with treatment |

| Pituitary disease | Hypersecretion of thyroid stimulating hormone, almost always by a pituitary adenoma[5] | Diffuse | Pituitary surgery | Very rare[5] | ||

| Graves' disease—also called Basedow syndrome | Autoantibodies (TSHR-Ab) that activate the TSH-receptor (TSHR) | Hyperthyroidism | Diffuse | Antithyroid agents, radioiodine, surgery | 1 to 2 cases per 1,000 population per year | Remission with treatment, but still lower quality of life for 14 to 21 years after treatment, with lower mood and lower vitality, regardless of the choice of treatment[6] |

| Thyroiditis | Acute or chronic inflammation | Can be hyperthyroidism initially, but progress to hypothyroidism | ||||

| Thyroid cancer | Usually uninodular | Overall relative 5-year survival rate of 85% for females and 74% for males[7] | ||||

| Benign thyroid neoplasms | Usually hyperthyroidism | Usually uninodular | Mostly harmless | |||

| Thyroid hormone insensitivity | Secretional hyperthyroidism, Symptomatical hypothyroidism |

Diffuse |

Epidemiology

Goitre is more common among women, but this includes the many types of goitre caused by autoimmune problems, and not only those caused by simple lack of iodine.

Treatment

Goitre is treated according to the cause. If the thyroid gland is producing too much T3 and T4, radioactive iodine is given to the patient to shrink the gland. If goitre is caused by iodine deficiency, small doses of iodide in the form of Lugol's Iodine or KI solution are given. If the goitre is associated with an underactive thyroid, thyroid supplements are used as treatment. In extreme cases, a partial or complete thyroidectomy is required.[9]

History

Chinese physicians of the Tang Dynasty (618–907) were the first to successfully treat patients with goitre by using the iodine-rich thyroid gland of animals such as sheep and pigs—in raw, pill, or powdered form.[10] This was outlined in Zhen Quan's (d. 643 AD) book, as well as several others.[11] One Chinese book, The Pharmacopoeia of the Heavenly Husbandman, asserted that iodine-rich sargassum was used to treat goitre patients by the 1st century BC, but this book was written much later.[12]

In the 12th century, Zayn al-Din al-Jurjani, a Persian physician, provided the first description of Graves' disease after noting the association of goitre and exophthalmos in his Thesaurus of the Shah of Khwarazm, the major medical dictionary of its time.[13][14] Al-Jurjani also established an association between goitre and palpitation.[15] The disease was later named after Irish doctor Robert James Graves, who described a case of goitre with exophthalmos in 1835. The German Karl Adolph von Basedow also independently reported the same constellation of symptoms in 1840, while earlier reports of the disease were also published by the Italians Giuseppe Flajani and Antonio Giuseppe Testa, in 1802 and 1810 respectively,[16] and by the English physician Caleb Hillier Parry (a friend of Edward Jenner) in the late 18th century.[17]

Paracelsus (1493–1541) was the first person to propose a relationship between goitre and minerals (particularly lead) in drinking water.[18] Iodine was later discovered by Bernard Courtois in 1811 from seaweed ash.

Goitre was previously common in many areas that were deficient in iodine in the soil. For example, in the English Midlands, the condition was known as Derbyshire Neck. In the United States, goitre was found in the Great Lakes, Midwest, and Intermountain regions. The condition now is practically absent in affluent nations, where table salt is supplemented with iodine. However, it is still prevalent in India, China[19] Central Asia and Central Africa.

Goitre had been prevalent in the alpine countries for a long time. Switzerland reduced the condition by introducing iodised salt in 1922. The Bavarian tracht in the Miesbach and Salzburg regions, which appeared in the 19th century, includes a choker, dubbed Kropfband (struma band) which was used to hide either the goitre or the remnants of goitre surgery.[20]

Society and culture

In the 1920s wearing bottles of iodine around the neck was believed to prevent goitre.[21]

Famous goitre sufferers

- Former President George H. W. Bush and his wife Barbara Bush both were diagnosed with Graves' disease and goitres, within two years of each other. In the president's case, the disease caused hyperthyroidism and cardiac dysrhythmia.[22][23] Scientists said that the odds of both George and Barbara Bush having Graves’ disease might be 1 in 100,000 or as low as 1 in 3,000,000[24]

- Andrea True (according to an interview on VH1)[25]

Goitre in fiction

- In the Seinfeld episode "The Old Man," Elaine Benes volunteers to visit an elderly female shut-in and discovers that the woman has a massive goitre. The goitre never appears on screen, but Elaine's subplot revolves around her inability to speak to the woman without looking at it.

- The character Big Nose in the Disney film Tangled suffers from a goitre, which he hopes will not interfere with his chances of finding love.[26]

- Charlotte Blacklock in the novel A Murder is Announced by Agatha Christie previously suffered from goitre.

- In the final scene of the movie Easy Rider, the redneck in the pickup truck who shoots Wyatt and Billy has a large goitre on the right side of his face.

- In the film The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, The Goblin King, played by Barry Humphries, is portrayed with a huge goitre hanging from his chin.

- In the Home Improvement episode "The Longest Day," the Taylors believe Randy may have serious thyroid cancer, but it turns out to be a goitre.

Heraldry

The coat of arms and crest of Die Kröpfner, of Tyrol showed a man "afflicted with a large goitre", an apparent pun on the German for the word.[27]

See also

- Struma ovarii—a kind of teratoma

- David Marine conducted substantial research on the treatment of goitre with iodine.

- Endemic goitre

References

- ^ "goiter" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ a b R. Hörmann: Schilddrüsenkrankheiten. ABW-Wissenschaftsverlag, 4. Auflage 2005, Seite 15-37. ISBN 3-936072-27-2

- ^ Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson. Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181f43e32, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181f43e32instead. - ^ a b Thyrotropin (TSH)-secreting pituitary adenomas. By Roy E Weiss and Samuel Refetoff. Last literature review version 19.1: January 2011. This topic last updated: July 2, 2009

- ^ Abraham-Nordling, Torring, Hamberger, Lundell, Tallstedt, Calissendorff, Wallin. Graves' Disease: A long-term quality-of-life follow-up of patients randomized to treatment with antithyroid drugs, radioiodine, or surgery, Thyroid 15, no. 11(2005), 1279-86

- ^ Numbers from EUROCARE, from Page 10 in: F. Grünwald; Biersack, H. J.; Grںunwald, F. (2005). Thyroid cancer. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-22309-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002" (xls). World Health Organization. 2002.

- ^ "Goiter - Simple". The New York Times.

- ^ Temple, Robert. (1986). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention. With a forward by Joseph Needham. New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc. ISBN 0-671-62028-2. Pages 133–134.

- ^ Temple, Robert. (1986). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention. With a forward by Joseph Needham. New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc. ISBN 0-671-62028-2. Page 134.

- ^ Temple, Robert. (1986). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention. With a forward by Joseph Needham. New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc. ISBN 0-671-62028-2. Pages 134–135

- ^ Basedow's syndrome or disease at Who Named It? - the history and naming of the disease

- ^ Ljunggren JG (1983). "[Who was the man behind the syndrome: Ismail al-Jurjani, Testa, Flagani, Parry, Graves or Basedow? Use the term hyperthyreosis instead]". Lakartidningen. 80 (32–33): 2902. PMID 6355710.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nabipour, I. (2003). "Clinical Endocrinology in the Islamic Civilization in Iran". International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1: 43–45 [45].

- ^ Giuseppe Flajani at Who Named It?

- ^ Hull G (1998). "Caleb Hillier Parry 1755-1822: a notable provincial physician". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 91 (6): 335–8. PMC 1296785. PMID 9771526.

- ^ "Paracelsus" Britannica

- ^ "In Raising the World’s I.Q., the Secret’s in the Salt", article by Donald G. McNeil, Jr., December 16, 2006, New York Times

- ^ Kropfband bei planet-wissen.de

- ^ "ARCHIVED - Why take iodine?". Nrc-cnrc.gc.ca. 2011-09-30. Retrieved 2012-11-01.

- ^ Robert G. Lahita and Ina Yalof. Women and Autoimmune Disease: The Mysterious Ways Your Body Betrays Itself. Page 158.

- ^ Lawrence K. Altman, M.D. “Doctors Say Bush Is in Good Health.” The New York Times. September 14, 1991.

- ^ Lawrence K. Altman, M.D. “The Doctor’s World; A White House Puzzle: Immunity Ailments.”, The New York Times. May 28, 1991]

- ^ “Andrea True.” Elle.

- ^ Disney Lyrics

- ^ Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (1904). The Art of Heraldry: An Encyclopædia of Armory. New York and London: Benjamin Blom, Inc. p. 413.

External links

- National Health Service, UK

- Network for Sustained Elimination of Iodine Deficiency

- Network for Sustained Elimination of Iodine Deficiency—alternate site at Emory University's School of Public Health

- A case and photograph of a huge goitre from Photobucket.com and Doctorkhodadoust.net

This template is no longer used; please see Template:Endocrine pathology for a suitable replacement