Great Plague of London

The Great Plague (1665–66) was the last major epidemic of the bubonic plague to occur in the Kingdom of England (part of modern-day United Kingdom). It happened within the centuries-long time period of the Second Pandemic, an extended period of intermittent bubonic plague epidemics which began in Europe in 1347, the first year of the "Black Death", and lasted until 1750.[1]

The Great Plague killed an estimated 100,000 people, about 15% of London's population.[2] Bubonic plague is a disease caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium, which is usually transmitted through the bite of an infected rat flea.[3]

The 1664–66 epidemic was on a far smaller scale than the earlier "Black Death" pandemic but was caused by a particularly virulent strain of the disease; it was remembered afterwards as the "great" plague mainly because it was the last widespread outbreak of bubonic plague in England during the four-hundred-year timespan of the Second Pandemic.[4][5]

Background

London in 1665

During the winter of 1664, a bright comet was to be seen in the sky[6] and the people of London were fearful, wondering what evil event it portended. London at that time consisted of a city of about 448 acres surrounded by a city wall, which had originally been built to keep out raiding bands. There were gates at Ludgate, Newgate, Aldersgate, Cripplegate, Moorgate and Bishopsgate and to the south lay the River Thames and London Bridge.[7] It was a city of great contrasts, ranging from large houses for the rich in Whitehall and Covent Garden employing several dozen servants, to town houses and timber-framed Tudor houses projecting over the streets, to tenements and garrets crowded with the poor people. There was no sanitation, and open drains flowed along the centre of winding streets. The cobbles were slippery with animal dung, garbage and the slops thrown out of the houses, muddy and buzzing with flies in summer and awash with sewage in winter. The City Corporation employed "rakers" to remove the worst of the filth and it was transported to mounds outside the walls where it accumulated and continued to decompose. The stench was overwhelming and people walked around with handkerchiefs or nosegays pressed against their nostrils.[8]

Some of the city's necessities such as coal arrived by barge, but most came by road. Carts, carriages, horses and pedestrians were crowded together and the gateways in the wall formed bottlenecks through which it was difficult to progress. The nineteen-arch London Bridge was even more congested. The better-off used hackney carriages and sedan chairs to get to their destinations without getting filthy. The poor walked, and might be splashed by the wheeled vehicles and drenched by slops being thrown out and water falling from the overhanging roofs. Another hazard was the choking black smoke belching forth from factories which made soap, from breweries and iron smelters and from about 15,000 houses burning coal.[9]

Outside the city walls, suburbs had sprung up providing homes for the craftsmen and tradespeople who flocked to the already overcrowded city. These were shanty towns with wooden shacks and no sanitation. The government had tried to control this development but had failed and over a quarter of a million people lived here.[10] Other immigrants had taken over fine town houses, vacated by Royalists who had fled the country during the Commonwealth, converting them into tenements with different families in every room. These properties were soon vandalised and became rat-infested slums.[10]

The recording of deaths

John Graunt estimated that altogether about 460,000 people lived in London in 1665. He was a demographer and made his estimate from bills of mortality which were published each week in the capital.[10] At that time, bubonic plague was a much feared disease but it was not understood how it was caused. The credulous blamed emanations from the earth, "pestilential effluviums", unusual weather, sickness in livestock, abnormal behaviour of animals or an increase in the numbers of moles, frogs, mice or flies.[11] It was not until 1894 that the identification by Alexandre Yersin of its causal agent Yersinia pestis was made and the transmission of the bacterium by rat fleas became known.[12]

When someone died in London, a bell was rung and a "searcher of the dead" arrived to inspect the corpse, aiming to determine the cause of death. Searchers were ignorant, venal old women who were paid a pittance for each report they made to the clerk who kept the records. In the case of a plague death, a searcher might be bribed to mis-state the true cause of death. This was because the infected house of a plague victim had, by law, to be shut up for forty days quarantine with all other members of the household inside. A plague house was marked with a red cross on the door with the words "Lord have mercy upon us", and a watchman stood guard outside.[10]

Outbreak

Early days

The 1665 outbreak of bubonic plague in England is thought to have spread from the Netherlands, where the disease had been occurring intermittently since 1599. It is unclear exactly where the disease first struck but the initial contagion may have arrived with Dutch trading ships carrying bales of cotton from Amsterdam, which was ravaged by the disease in 1663–1664, with a mortality given of 50,000.[13] The dock areas outside London and the parish of St Giles in the Fields, where poor workers were crowded into ill-kept structures, are believed to be the first areas to be struck. Two suspicious deaths were recorded in that parish in December 1664 and another in February 1665. These did not appear as plague deaths on the Bills of Mortality, so no control measures were taken by the authorities, but the total number of people dying in London during the first four months of 1665 showed a marked increase. By the end of April only four plague deaths had been recorded, but total deaths per week had risen from around 290 to 398.[14]

It had been a hard winter but with the arrival of warmer weather, the disease began to take a firmer hold. The only parishes involved at first were St Andrew, Holborn, St Giles in the Fields, St Clement Danes and St Mary Woolchurch Haw. Only the last was actually inside the City of London, the others being part of the suburbs. People began to be alarmed. Samuel Pepys, who had an important position at the Admiralty, stayed in London and provided a contemporary account of the plague through his diary.[15] On 30th April he wrote: "Great fears of the sickness here in the City it being said that two or three houses are already shut up. God preserve us all!"[16] Another source of information on the time is a fictional account, A Journal of the Plague Year, which was written by Daniel Defoe and published in 1722. He was only six when the plague struck but made use of his family's recollections (his uncle was a saddler in East London and his father a butcher in Cripplegate), interviews with survivors and sight of such official records as were available.[17]

Exodus from the city

By July 1665, plague was rampant in the City of London. King Charles II of England, his family and his court left the city for Salisbury, moving on to Oxford in September when some cases of plague occurred in Salisbury.[18] The aldermen and most of the other city authorities opted to stay at their posts. The Lord Mayor of London, Sir John Lawrence, also decided to stay in the city. Businesses were closed when merchants and professionals fled. Defoe wrote "Nothing was to be seen but wagons and carts, with goods, women, servants, children, coaches filled with people of the better sort, and horsemen attending them, and all hurrying away".[15] As the plague raged throughout the summer, only a small number of clergymen, physicians and apothecaries remained to cope with an increasingly large number of victims. Edward Cotes, author of "London's Dreadful Visitation", expressed the hope that "Neither the Physicians of our Souls or Bodies may hereafter in such great numbers forsake us".[15]

The poorer people were also alarmed by the contagion and some left the city, but it was not easy for them to abandon their accommodation and livelihoods for an uncertain future elsewhere. Before exiting through the city gates, they were required to possess a certificate of good health signed by the Lord Mayor and these became increasingly difficult to obtain. As time went by and the numbers of plague victims rose, people living in the villages outside London began to resent this exodus and were no longer prepared to accept townsfolk from London, with or without a certificate. The refugees were turned back, were not allowed to pass through towns and had to travel across country, and were forced to live rough on what they could steal or scavenge from the fields. Many died in wretched circumstances of starvation and thirst in the hot summer that was to follow.[19]

Height of the epidemic

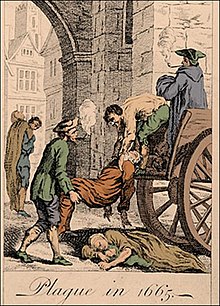

In the last week of July, the London Bill of Mortality showed 3,014 deaths, of which 2,020 had died from the plague. The number of deaths as a result of plague may have been underestimated, as deaths in other years in the same period were much lower, at around 300. As the number of victims affected mounted up, burial grounds became overfull, and pits were dug to accommodate the dead. Drivers of dead-carts travelled the streets calling "Bring out your dead" and carted away piles of bodies. The authorities became concerned that the number of deaths might cause public alarm and ordered that body removal and interment should take place only at night.[20] As time went on, there were too many victims, and too few drivers, to remove the bodies which began to be stacked up against the walls of houses. Daytime collection was resumed and the plague pits became mounds of decomposing corpses. In the parish of Aldgate, a great hole was dug near the churchyard, fifty feet long and twenty feet wide. Digging was continued by labourers at one end while the dead-carts tipped in corpses at the other. When there was no room for further extension it was dug deeper till ground water was reached at twenty feet. When finally covered with earth it housed 1,114 corpses.[21]

Plague doctors traversed the streets diagnosing victims, although many of them had no formal medical training. Several public health efforts were attempted. Physicians were hired by city officials and burial details were carefully organized, but panic spread through the city and, out of the fear of contagion, people were hastily buried in overcrowded pits. The means of transmission of the disease were not known but thinking they might be linked to the animals, the City Corporation ordered a cull of dogs and cats.[22] This decision may have affected the length of the epidemic since those animals could have helped keep in check the rat population carrying the fleas which transmitted the disease. Thinking bad air was involved in transmission, the authorities ordered giant bonfires to be burned in the streets and house fires to be kept burning night and day, in hopes that the air would be cleansed.[23] Tobacco was thought to be a prophylactic and it was later said that no London tobacconist had died from the plague during the epidemic.[24]

Trade and business had completely dried up, and the streets were empty of people except for the dead-carts and the desperate dying victims. That people did not starve was down to the foresight of Sir John Lawrence and the Corporation of London who arranged for a commission of one farthing to be paid above the normal price for every quarter of corn landed in the Port of London.[25] Another food source was the villages around London which, denied of their usual sales in the capital, left vegetables in specified market areas, negotiated their sale by shouting, and collected their payment after the money had been left submerged in a bucket of water to "disinfect" the coins.[25]

Records state that plague deaths in London and the suburbs crept up over the summer from 2,000 people per week to over 7,000 per week in September. These figures are likely to be a considerable underestimate. Many of the sextons and parish clerks who kept the records were themselves dead. Quakers refused to co-operate and many of the poor were just dumped into mass graves unrecorded. It is not clear how many people caught the disease and made a recovery because only deaths were recorded and many records were destroyed in the Great Fire of London the following year. In the few districts where intact records remain, plague deaths varied between 30% and over 50% of the total population.[26]

Though concentrated in London, the outbreak affected other areas of the country as well. Perhaps the most famous example was the village of Eyam in Derbyshire. The plague allegedly arrived with a merchant carrying a parcel of cloth sent from London, although this is a disputed point. The villagers imposed a quarantine on themselves to stop the further spread of the disease. This prevented the disease from moving into surrounding areas but the cost to the village was the death of around 80% of its inhabitants over a period of fourteen months.[27]

Aftermath

By late autumn, the death toll in London and the suburbs began to slow until, in February 1666, it was considered safe enough for the King and his entourage to come back to the city. With the return of the monarch, other people began to come back. The gentry returned in their carriages accompanied by carts piled high with their belongings. The judges moved back from Windsor to sit in Westminster Hall, although Parliament, which had been prorogued in April 1665, did nor reconvene until September, 1666. Trade recommenced and businesses and workshops opened up. London was the goal of a new wave of people who flocked to the city in expectation of making their fortunes. Writing at the end of March 1666, Lord Clarendon, the Lord Chancellor, stated "... the streets were as full, the Exchange as much crowded, the people in all places as numerous as they had ever been seen ...".[28]

Plague cases continued to occur sporadically at a modest rate until the summer of 1666. On the second and third of September that year, the Great Fire of London destroyed much of the City of London, and some people believed that the fire put an end to the epidemic. However, it is now thought that the plague had largely subsided before the fire took place. In fact, most of the later cases of plague were found in the suburbs,[28] and it was the City of London itself that was destroyed by the Fire.[29]

According to the Bills of Mortality, there were in total 68,596 deaths in London from the plague in 1665. Lord Clarendon estimated that the true number of mortalities was probably twice that figure. The next year, 1666, saw further deaths in other cities but on a lesser scale. Dr Thomas Gumble, chaplain to the Duke of Albermarle, both of whom had stayed in London for the whole of the epidemic, estimated that the total death count for the country from plague during 1665 and 1666 was about 200,000.[28]

The Great Plague of 1665/1666 was the last major outbreak of bubonic plague in Great Britain. It spread to some other towns in the southeast of England but fewer than ten percent of a sample of parishes outside London had higher than expected mortalities during those years. Urban areas were more affected than rural ones; Norwich, Ipswich, Colchester, Southampton and Winchester were badly affected while the Midlands escaped altogether.[30]

Impact

The plague in London largely affected poor people, while the rich could, and did, leave the city and retire to their country estates or go to reside with kin in other parts of the country. The Great Fire however ruined many city merchants and property owners.[28] As a result of these events, London was largely rebuilt and Parliament enacted the Rebuilding of London Act 1666.[31] The street plan of the capital was relatively unchanged but the streets were widened, pavements were created, open sewers abolished, wooden buildings and overhanging gables forbidden, and the design and construction of buildings controlled. The use of brick or stone was mandatory and many gracious buildings were constructed. Not only was the capital rejuvenated, but it became a much more healthy environment in which to live. Londoners had a greater sense of community after they had overcome the great adversities of 1665 and 1666.[32]

Rebuilding took over ten years and was supervised by Robert Hooke as Surveyor of London.[33] The architect Sir Christopher Wren was involved in the rebuilding of St Paul's Cathedral and more than fifty London churches.[34] King Charles ll did much to foster the rebuilding work. He was a patron of the arts and sciences and founded the Royal Observatory and supported the Royal Society, a scientific group whose early members included Robert Hooke, Robert Boyle and Sir Isaac Newton. In fact, out of the fire and pestilence flowed a renaissance in the arts and sciences in England.[32]

See also

- Loimologia, a first-hand account of the 1665 plague

- Beak doctor costume

- Black Death in England

- Derby plague of 1665

- Great Plague of Vienna of 1679

- Plague doctor contract

- Plague! The Musical, a musical loosely based on the 1665 plague

- Ring a Ring o' Roses, a nursery rhyme, commonly believed to have arisen at this time

References

- ^ Haensch, Stephanie; et al. (2010). "Distinct Clones of Yersinia pestis Caused the Black Death". PLoS Pathogens. 6 (10): e1001134. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001134.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "The Great Plague of London 1665-6". nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "Backgrounder: Plague". AVMA: Public Health. American Veterinary Medical Association. 27 November 2006. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- ^ "Spread of the Plague". Bbc.co.uk. 29 August 2002. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Ibeji, Mike (10 March 2011). "Black Death". BBC. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ Pepys, Samuel (1665). "March 1st". Diary of Samuel Pepys. ISBN 0-520-22167-2.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Leasor (1962) pp. 12–13

- ^ Leasor (1962) pp. 14–15

- ^ Leasor (1962) pp. 18–19

- ^ a b c d Leasor (1962) pp. 24–27

- ^ Leasor (1962) p. 42

- ^ Bockemühl J (1994). "100 years after the discovery of the plague-causing agent--importance and veneration of Alexandre Yersin in Vietnam today". Immun Infekt. 22 (2): 72–5. PMID 7959865.

- ^ Appleby, Andrew B. (1980). "The Disappearance of Plague: A Continuing Puzzle". The Economic History Review. 33 (2): 161–173. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1980.tb01821.x.

- ^ Leasor (1962) pp. 46–50

- ^ a b c Leasor (1962) pp. 60–62

- ^ Pepys, Samuel (1665). "April 30th". Diary of Samuel Pepys. ISBN 0-520-22167-2.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Leasor (1962) pp. 47, 62

- ^ Leasor (1962) p. 103

- ^ Leasor (1962) pp. 66–69

- ^ Leasor (1962) pp. 141–145

- ^ Leasor (1962) pp. 174–175

- ^ Moote, Lloyd and Dorothy: The Great Plague: the Story of London's most Deadly Year, Baltimore, 2004. p. 115.

- ^ Leasor (1962) pp. 166–169

- ^ Porter, Stephen (2009). The Great Plague. Amberley Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 9781848680876.

- ^ a b Leasor (1962) pp. 99–101

- ^ Leasor (1962) pp. 155–156

- ^ Coleman, Michel P. (1986). "A Plague Epidemic in Voluntary Quarantine". International Journal of Epidemiology. 15 (3): 379–385. doi:10.1093/ije/15.3.379.

- ^ a b c d Leasor (1962) pp. 193–196

- ^ Leasor (1962) pp. 250–251

- ^ Porter, Stephen (2009). The Great Plague. Amberley Publishing. pp. 136–137. ISBN 9781848680876.

- ^ "An Act for rebuilding the City of London". Statutes of the Realm: volume 5 - 1628-80, pp.603–612. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ a b Leasor (1962) pp. 269–271

- ^ The Rebuilding of London After the Great Fire. Thomas Fiddian. 1940. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ Hart, Vaughan (2002). Nicholas Hawksmoor: Rebuilding Ancient Wonders. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09699-6.

Bibliography

- Arnold, Catherine (2006). Necropolis: London and its dead. London: Simon and Schuster.

- Bell, Walter George (1924). The Great Plague in London in 1665. Michigan: AMS Press. ISBN 978-1-85891-218-9.

- Leasor, James (1962). The Plague and the Fire. London: George Allen and Unwin. ISBN 978-0-75510-040-8.

- Moote, A. Lloyd (2008). The Great Plague: The Story of London's Most Deadly Year. London: JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-80189-230-1.

- Porter, Stephen (2012). The Great Plague of London. Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-44560-773-3.

External links