The Negro Motorist Green Book

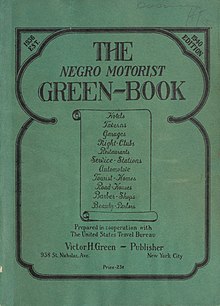

Cover of the 1940 edition | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Victor H. Green |

| Published | 1936–1966 |

The Negro Motorist Green Book was an annual guidebook for African-American drivers which was commonly referred to simply as the "Green Book". It was published in the United States from 1936 to 1966, during the Jim Crow era when discrimination against non-whites was widespread. Although mass automobility was predominantly a white phenomenon due to pervasive racial discrimination and black poverty, the level of car ownership among African-Americans grew as a black middle class emerged. Many blacks took to driving,[1] particularly in order to avoid segregation on public transportation.[2] As the writer George Schuyler put it in 1930, "all Negroes who can do so purchase an automobile as soon as possible in order to be free of discomfort, discrimination, segregation and insult."[3] Black Americans employed as salesmen, entertainers and athletes also found themselves traveling more often for work purposes.[4]

However, African-American travelers faced a variety of dangers and inconveniences, ranging from white-owned businesses refusing to serve them (or repair their vehicles), to being refused accommodation or food, or even threats of physical violence and forcible expulsion from whites-only "sundown towns". New York mailman and travel agent Victor H. Green published The Negro Motorist Green Book to tackle such problems and "to give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trip more enjoyable."[5] From a New York-focused first edition published in 1936, it expanded to cover much of North America including most of the United States and part of Canada, Mexico and Bermuda. The Green Book became "the bible of black travel during Jim Crow",[6] enabling black travelers to find lodgings, businesses and gas stations that would serve them along the road. Outside the African-American community, however, it was little known. It fell into obscurity after it ceased publication shortly after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed the types of racial discrimination that had made the book necessary. Interest in it has revived in recent years in connection with studies of black travel during the Jim Crow era.

Traveling while black

Black drivers faced major problems to which most whites were oblivious. White supremacists had long sought to restrict black mobility; simply undertaking a road journey was potentially dangerous for many blacks. They were subjected to racial profiling by police departments ("driving while black"), faced being punished for being "uppity" or "too prosperous" if they were seen driving a car (regarded by many whites as a white prerogative), and risked physical harassment ranging from arrest to lynching. In 1948 one black driver, Robert Mallard, was lynched in his brand-new car in front of his wife and child by a white mob in Georgia which allegedly saw him as being "not the right kind of negro"[7] and "nigger rich".[8] The NAACP's magazine The Crisis had highlighted the uphill struggle that blacks faced in undertaking recreational travel in a bitter commentary published in 1947: "Would a Negro like to pursue a little happiness at a theater, a beach, pool, hotel, restaurant, on a train, plane, or ship, a golf course, summer or winter resort? Would he like to stop overnight at a tourist camp while he motors about his native land "Seeing America First"? Well, just let him try!"[9]

Racist laws, discriminatory social codes and segregated commercial facilities made road journeys a minefield of constant uncertainty and risk. The difficulties of travel for black Americans were such that, as Lester B. Granger of the National Urban League put it, "so far as travel is concerned, Negroes are America's last pioneers."[1] Businesses across the United States refused to serve African-Americans. Black travelers often had to carry buckets or portable toilets in the trunks of their cars because they were usually barred from bathrooms and rest areas in service stations and roadside stops. Diners and restaurants also rejected blacks, and even travel essentials such as gasoline could be unavailable due to discrimination at gas stations.[10] To avoid such problems on long trips, African-Americans often packed meals and even containers of gasoline in their cars.[6] The civil rights leader John Lewis recalls how his family prepared for a trip in 1951:

There would be no restaurant for us to stop at until we were well out of the South, so we took our restaurant right in the car with us... Stopping for gas and to use the bathroom took careful planning. Uncle Otis had made this trip before, and he knew which places along the way offered "colored" bathrooms and which were better just to pass on by. Our map was marked and our route was planned that way, by the distances between service stations where it would be safe for us to stop."[11]

Finding accommodation was one of the greatest challenges faced by black travellers. Not only did many hotels, motels and boarding houses refuse to serve black customers, but thousands of towns across America declared themselves "sundown towns" which all non-whites had to leave by sunset.[1] They were not simply a phenomenon of the South (in fact, white Southerners disliked the practice, as it would have deprived them of black labour). Huge numbers of American towns across the entire country were effectively off-limits to African-Americans. By the end of the 1960s, there were at least 10,000 sundown towns across America – including large suburbs such as Glendale, California (population 60,000 at the time), Levittown, New York (80,000) and Warren, Michigan (180,000). Over half the incorporated communities in Illinois were sundown towns. The unofficial slogan of Anna, Illinois, which had violently expelled its African-American population in 1909, was "Ain't No Niggers Allowed".[12] Even in towns which did not exclude overnight stays by blacks, accommodations were often very limited. Of the more than 100 motels that lined U.S. Route 66 in Albuquerque, New Mexico, less than six percent admitted black customers.[13] In the whole of the state of New Hampshire in 1956, only three motels served African-Americans.[14]

The risky nature of African-American travel was reflected in the fact that their road trip narratives have often had a very different outlook from their more utopian white counterparts, highlighting the constant anxiety experienced by black travelers in the United States. The black journalist Courtland Milloy recalled the menacing environment that black travelers faced during his childhood, in which "so many ... were just not making it to their destinations."[15] John A. Williams wrote in his 1965 book This Is My Country Too that he did not believe that "white travelers have any idea of how much nerve and courage it requires for a Negro to drive coast to coast in America." He achieved it with "nerve, courage, and a great deal of luck," supplemented by "a rifle and shotgun, a road atlas, and Travelguide, a listing of places in America where Negroes can stay without being embarrassed, insulted, or worse." He noted the need to be particularly cautious in the South, where black drivers were advised to wear a chauffeur's cap or have one visible on the front seat and pretend that they were delivering a car for a white person. Along the way, he wrote, he had to endure a stream of "insults of clerks, bellboys, attendants, cops, and strangers in passing cars." There was a constant need to keep his mind on the danger he faced as a solo black driver; as he was well aware, "[black] people have a way of disappearing on the road."[16] Even long after the Jim Crow era had officially finished, traveling while black remained difficult. Eddy L. Harris's account of a motorcycle journey alongside the entire length of the Mississippi River describes how he was "glared at, threatened, turned away, called names, and made afraid." The trip was undertaken in 1988.[15]

Navigating Jim Crow: the role of the Green Book

To help black drivers navigate these pitfalls, African-American writers produced a number of guides to provide advice on traveling. These included directories of which hotels, camps, road houses, and restaurants would serve African-Americans. Among the best known were The Negro Motorist Green Book and Travelguide (Vacation and Recreation Without Humiliation). The Green Book was conceived in 1932 and first published in 1936 by Victor H. Green, a World War I veteran from New York City who worked as a postal carrier and travel agent. He said that his aim was "to give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trip more enjoyable."[5] According to an editorial written by Novera C. Dashiell in the spring 1956 edition of the Green Book, "the idea crystallized when not only [Green] but several friends and acquaintances complained of the difficulties encountered; oftentimes painful embarrassments suffered which ruined a vacation or business trip."[17]

Similar handbooks had been published for the Jewish-American community, which also faced widespread discrimination, though at least Jews were able to blend in more easily into the general population.[18] Green commented in 1940 that the Green Book had given black Americans "something authentic to travel by and to make traveling better for the Negro."[19] The Green Book was initially published locally in New York, but its popularity was such that from 1937 it was distributed nationally with input from Charles McDowell, a collaborator on Negro Affairs for the United States Travel Bureau, a government agency.[5] Its motto, displayed on the front cover, was for black travelers to "carry your Green Book with you – You may need it".[17] The 1949 edition also included a quote from Mark Twain: "Travel is fatal to prejudice," inverting Twain's original meaning; as Cotton Seiler puts it, "here it was the visited, rather than the visitors, who would find themselves enriched by the encounter."[20]

The Green Book's principal aim was to provide accurate information on black-friendly accommodations to answer the constant question that faced all black drivers: "Where will you spend the night?" As well as essential information on lodgings, service stations and garages, it also provided details of leisure facilities open to African-Americans, including beauty salons, restaurants, nightclubs and country clubs.[21] The listings focused on four main categories – hotels, motels, tourist homes (private residence, usually owned by African-Americans, which provided accommodation to travelers) and restaurants. They were arranged by state, subdivided by city, giving the name and address of each. For an extra payment, the listed businesses could have their listing displayed in bold type or to have a star next to it to denote that they were "recommended."[14] Many such establishments were run by and for African-Americans, and in some cases were named after prominent figures in African-American history; in North Carolina, for instance, they included the Carver, Lincoln and Booker T. Washington hotels; the Friendly City beauty parlor; the Black Beauty Tea Room; the New Progressive tailor shop; the Big Buster tavern and Blue Duck Inn.[22] Each edition also included feature articles on travel and destinations[23] and included a listing of black resorts such as Idlewild, Michigan, Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts and Belmar, New Jersey.[24] Green asked his readers to provide information "on the Negro motoring conditions, scenic wonders in your travels, places visited of interest and short stories on one's motoring experience." He offered a bounty of a dollar for each accepted account, which he increased to five dollars by 1941.[19]

Impact

The Green Book attracted sponsorship from a number of businesses, including the African-American newspapers Call and Post of Cleveland, Ohio and the Louisville Leader of Louisville, Kentucky.[25] Standard Oil (later Esso) was also a sponsor, due to the efforts of James "Billboard" Jackson, a pioneering African-American sales representative of the company.[19] Esso's "race group", part of its marketing division, promoted the Green Book as enabling Esso's black customers to "go further with less anxiety". (By contrast, Shell gas stations were known to refuse black customers.)[26] The 1949 edition included an Esso endorsement message that told readers: "As representatives of the Esso Standard Oil Co., we are pleased to recommend the Green Book for your travel convenience. Keep one on hand each year and when you are planning your trips, let Esso Touring Service supply you with maps and complete routings, and for real 'Happy Motoring' – use Esso Products and Esso Service wherever you find the Esso sign."[13]

Although Green usually refrained from editorialising in the Green Book, he let his readers' letters speak for the impact that his publication had. William Smith of Hackensack, New Jersey called it "a credit to the Negro Race" in a letter published in the 1938 edition. He commented: "It is a book badly needed among our Race since the advent of the motor age. Realizing the only way we knew where and how to reach our pleasure resorts was in a way of speaking, by word of mouth, until the publication of The Negro Motorist Green Book ... We earnestly believe that [it] will mean as much if not more to us as the A.A.A. means to the white race."[25] Earl Hutchinson Sr., the father of journalist Earl Ofari Hutchinson, wrote in his autobiographical account of a 1955 move from Chicago to California that "you literally didn't leave home without [the Green Book]."[27] Ernest Green, one of the Little Rock Nine, used the Green Book to navigate the 1,000 miles (1,600 km) from Arkansas to Virginia in the 1950s and comments that "it was one of the survival tools of segregated life".[28] As the civil rights leader Julian Bond has said, recalling his parents' use of the Green Book, "it was a guidebook that told you not where the best places were to eat, but where there was any place."[4] Bond comments:

You think about the things that most travelers take for granted, or most people today take for granted. If go to New York City and want a hair cut, it's pretty easy for me to find a place where that can happen, but it wasn't easy then. White barbers would not cut black peoples' hair. White beauty parlors would not take black women as customers — hotels and so on, down the line. You needed the Green Book to tell you where you can go without having doors slammed in your face.[18]

While the Green Book sought to make life easier for those living under Jim Crow, it looked forward to a time when such guidebooks would no longer be necessary. As Green wrote, "there will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go as we please, and without embarrassment."[27]

Publishing history

Published continuously from 1936 to 1940, the Green Book's publication was suspended during World War II and resumed in 1946.[29] Its scope expanded greatly during its years of publication; from covering only the New York area in the first edition, it eventually covered most of the United States and parts of Canada (primarily Montréal), Mexico and Bermuda. Coverage was good in the eastern US and weak in plains states such as North Dakota. It eventually sold around 15,000 copies per year, distributed by mail order, through black-owned businesses and through Esso service stations, some of which – unusual for the oil industry at the time – were franchised to African-Americans.[4] It originally sold for 25 cents, increasing to $1.25 by 1957.[30] With the book's growing success, Green retired from the post office and hired a small publishing staff that operated from 200 West 135th Street in Harlem. He also established a vacation reservation service in 1947 to take advantage of the post-war boom in automobile travel.[13] From ten pages in its first edition,[26] by 1949 the Green Book had expanded to more than 80 pages including advertisements. In 1952 Green renamed the publication as The Negro Travelers Green Book, in recognition of its expansion to cover international destinations that would not have been reached by car.[13]

By the start of the 1960s the Green Book's market was already beginning to erode, even before the passage of civil rights legislation later in the decade. An increasing number of middle-class African-Americans were beginning to question whether guides such as the Green Book were in fact accommodating Jim Crow by steering black travelers to segregated businesses, rather than pushing for equal access. The quality of black-owned lodgings was also coming under scrutiny, as they were felt by many prosperous blacks to be second-rate compared to the higher-quality white-owned lodgings from which they were excluded. The 1951 Green Book told black-owned businesses to raise their standards as travelers were "no longer content to pay top prices for inferior accommodations and services." Black-owned motels in remote locations off state highways found themselves losing out to a new generation of integrated interstate motels. The 1963 Green Book acknowledged that the activism of the civil rights movement had "widened the areas of public accommodations accessible to all" but defended the continued listing of black-friendly businesses because "a family planning for a vacation hopes for one that is free of tensions and problems."[31] The 1966 edition was the last to be published after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made the guide obsolete by outlawing racial discrimination by facilities that served the general public ("public accommodations").[13]

Legacy

In the 2000s, interest in the Green Book was revived by writers, artists, academics and curators exploring the history of African-American travel in the United States during the Jim Crow era. It featured in a traveling exhibition called "The Dresser Trunk Project" that was organised in 2007 by William Daryl Williams, the director of the School of Architecture and Interior Design at the University of Cincinnati. The exhibition drew on the Green Book to highlight artifacts and locations associated with black travel during segregation.[4]

The African-American playwright Calvin Alexander Ramsey wrote a play called The Green Book which made its world debut in Atlanta in August 2011.[30] It centers on a tourist home in Jefferson, Missouri. A black military officer, his wife and a Jewish survivor of the Holocaust all spend the night in the home just before the civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois is scheduled to deliver a speech in town. The Jewish traveler comes to the home after being shocked to find that the hotel where he planned to stay has a "No Negroes Allowed" posted in its lobby – an allusion to the problems of discrimination that Jews and blacks both faced at the time.[4] Ramsey has also written a children's book, Ruth and the Green Book, about a Chicago family's journey to Alabama in 1952 in which the Green Book is used to guide their way.[28]

The University of South Carolina has produced a custom Google Map displaying the locations of over 1,500 places listed in the Spring 1956 Green Book, including a searchable index.

References

- ^ a b c Seiler, p. 87

- ^ Franz, p. 241

- ^ Franz, p. 242

- ^ a b c d e McGee, Celia (August 22, 2010). "The Open Road Wasn't Quite Open to All". The New York Times. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c Franz, p. 246

- ^ a b Freedom du Lac, J. (September 12, 2010). "Guidebook that aided black travelers during segregation reveals vastly different D.C." The Washington Post. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ Seiler, p. 88

- ^ "Widow Of Lynch Victim Sobs Out Her Grief". Life. January 24, 1949. p. 35.

- ^ "Democracy Defined at Moscow". The Crisis. April 1947. p. 105.

- ^ Sugrue, Thomas J. "Driving While Black: The Car and Race Relations in Modern America". Automobile in American Life and Society. University of Michigan. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ Wright, pp. 75–76

- ^ Loewen, pp. 15–16

- ^ a b c d e Hinckley, p. 127

- ^ a b Rugh, p. 77

- ^ a b Seiler, p. 83

- ^ Primeau, p. 117

- ^ a b Goodavage, Maria (January 10, 2013). "'Green Book' Helped Keep African Americans Safe on the Road". PBS. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ^ a b "'Green Book' Helped African-Americans Travel Safely". NPR. September 15, 2010. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ^ a b c Seiler, p. 90

- ^ Seiler, p. 92

- ^ Seiler, p. 91

- ^ Powell, Lew (August 27, 2010). "Traveling while black: A Jim Crow survival guide". University of North Carolina Library. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ Rugh, p. 78

- ^ Rugh, p. 168

- ^ a b Seiler, p. 89

- ^ a b Lewis, p. 269

- ^ a b Seiler, p. 94

- ^ a b Lacey-Bordeaux, Emma; Drash, Wayne (February 25, 2011). "Travel guide helped African-Americans navigate tricky times". CNN. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ Landry, p. 57

- ^ a b Towne, Douglas (July 2011). "African-American Travel Guide". Phoenix Magazine. p. 46. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ Rugh, p. 84

Bibliography

- Franz, Kathleen; Smulyan, Susan, eds. (2011). "Cars as Popular Culture: Democracy, Racial Difference, and New Technology, 1920-1939". Major Problems in American Popular Culture. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781133417170.

- Hinckley, Jim (2012). The Route 66 Encyclopedia. Voyageur Press. ISBN 9780760340417.

- Landry, Bart (1988). The New Black Middle Class. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520908987.

- Lewis, Tom (2013). Divided Highways: Building the Interstate Highways, Transforming American Life. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801467820.

- Loewen, James W. (2006). "Sundown Towns". In Hartman, Chester W. (ed.). Poverty & Race in America: The Emerging Agendas. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739114193.

- Primeau, Ronald (1996). Romance of the Road: The Literature of the American Highway. Popular Press. ISBN 9780879726980.

- Rugh, Susan Sessions (2010). Are We There Yet?: The Golden Age of the American Family Vacation. University of Kansas Publications. ISBN 9780700617593.

- Seiler, Cotton (2012). ""So That We as a Race Might Have something Authentic to Travel By": African-American Automobility and Cold-War Liberalism". In Slethaug, Gordon E.; Ford, Stacilee (eds.). Hit the Road, Jack: Essays on the Culture of the American Road. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 9780773540767.

- Wright, Gavin (2013). Sharing the Prize. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674076495.

External links