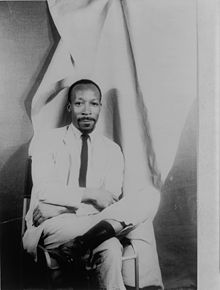

John A. Williams

John A. Williams | |

|---|---|

Williams in 1962 (photo by Carl van Vechten) | |

| Born | John Alfred Williams December 5, 1925 Jackson, Mississippi, US |

| Died | July 3, 2015 (aged 89) Paramus, New Jersey, US |

| Occupation |

|

| Alma mater | Syracuse University |

| Notable works | The Man Who Cried I Am (1967) |

| Notable awards | American Book Award |

| Spouse | Lori Isaac (m. 1965) |

John Alfred Williams (December 5, 1925 – July 3, 2015) was an African American author, journalist, and academic. His novel The Man Who Cried I Am was a bestseller in 1967.[1] Also a poet, he won an American Book Award for his 1998 collection Safari West.[2]

Life and career

[edit]Williams was born in Jackson, Mississippi, and his family moved to Syracuse, New York. After naval service in World War II, he graduated in 1950 from Syracuse University. He was a journalist for Ebony (his September 1963 Ebony article "Negro In Literature Today" has been singled out for particular praise),[3][4] Jet, and Newsweek magazines.[5]

His novels, which include The Angry Ones (1960) and The Man Who Cried I Am (1967), are mainly about the black experience in white America. The Man Who Cried I Am, a fictionalized account of the life and death of African-American writer Richard Wright, introduced the King Alfred Plan – a fictional CIA-led scheme supporting an international effort to eliminate people of African descent. This "plan" has since been cited as fact by some members of the Black community and conspiracy theorists.[citation needed] Sons of Darkness, Sons of Light: A Novel of Some Probability (1969) imagines a race war in the United States.[6] The novel begins as a thriller with aspects of detective fiction and spy fiction, before transitioning to apocalyptic fiction at the point when the characters' revolt begins.[7]

In the early 1980s, Williams and the composer and flautist Leslie Burrs, with the agreement of Mercer Ellington, began collaborating on the completion of Queenie Pie, an opera by Duke Ellington that had been left unfinished at Ellington's death. The project fell through, and the opera was eventually completed by other hands.[8]

In 2003, Williams performed a spoken-word piece on Transform, an album by rock band Powerman 5000. At the time, his son Adam Williams was the band's guitarist.

Personal life

[edit]Williams married Lori Isaac in 1965 and moved in 1975 from Manhattan to Teaneck, New Jersey, as it was a place that "would not be inhospitable to a mixed marriage".[9]

Dear Chester, Dear John, a collection of personal letters between Williams and Chester Himes, who had met in 1961 and maintained a lifelong friendship, was published in 2008.

Honorable recognitions

[edit]In 1970, Williams received the Syracuse University Centennial Medal for Outstanding Achievement,[10] in 1983 his novel !Click Song won the American Book Award,[11] and in 1998, his book of poetry Safari West also won the American Book Award.[11] On October 16, 2011, he received a Lifetime Achievement award from the American Book Awards.[12]

Death

[edit]Williams died on July 3, 2015, in Paramus, New Jersey, aged 89. He had Alzheimer's disease.[13]

Legacy

[edit]Williams' personal papers, including correspondence and photographs, are held at Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus Libraries at the University of Rochester.[14] There is also a collection of Williams' papers at the Special Collections Research Center[15] at Syracuse University.

Selected bibliography

[edit]Novels

[edit]- The Angry Ones, Norton, 1960, 9780393314649; The Angry Ones: A Novel. Open Road Media. February 2, 2016. ISBN 978-1-5040-2591-1.

- Night Song, Farrar, Straus and Cudahy, 1961; Night Song: A Novel. Open Road Media. February 2, 2016. ISBN 978-1-5040-2572-0.

- Sissie, Farrar, Straus and Cudahy, 1963; Chatham Bookseller, 1975, ISBN 9780911860535

- The Man Who Cried I Am, Little, Brown, 1967; The Man Who Cried I Am: A Novel. Library of America. November 7, 2023. ISBN 978-1598537611.

- Sons of Darkness, Sons of Light, Little, Brown, 1969; Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1970, ISBN 9780413446206

- Captain Blackman, Coffee House Press, 1972, ISBN 9781566890960 Captain Blackman: A Novel. Open Road Media. February 2, 2016. ISBN 978-1-5040-3264-3.

- Mothersill and the Foxes, Doubleday, 1975, ISBN 9780385094542

- The Junior Bachelor Society, Doubleday, 1976, ISBN 9780385094559

- !Click Song, 1982 ISBN 9780395318416; !Click Song: A Novel. Open Road Media. February 2, 2016. ISBN 978-1-5040-3304-6.

- The Berhama Account, New Horizon Press Publishers, 1985, ISBN 9780882820095

- Jacob's Ladder, New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 1987; 1989, ISBN 9780938410768

- Clifford's Blues, Coffee House Press, 1999, ISBN 9781566890809; Clifford's Blues: A Novel. Open Road Media. February 2, 2016. ISBN 978-1-5040-3305-3.

Non-fiction

[edit]- Africa: Her History, Lands and People: Told with Pictures. Rowman & Littlefield. 1962. ISBN 978-0-8154-0258-9.

- This Is My Country Too (New American Library, 1965)[16]

- The King God Didn't Save: Reflections on the Life and Death of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1970)

- The Most Native of Sons: A Biography of Richard Wright (1970)

- Flashbacks: A Twenty-Year Diary of Article Writing (1973)

- If I Stop I'll Die: The Comedy and Tragedy of Richard Pryor (Thunder's Mouth Press, 1991)

Poetry

[edit]- Safari West: Poems (Hochelaga Press, 1998)

Letters

[edit]- Dear Chester, Dear John: Letters between Chester Himes and John A. Williams (compiled and edited with Lori Williams), Wayne State University Press, 2008, ISBN 9780814333556

References

[edit]- ^ Marnie Eisenstadt, "Author John A. Williams dies; Syracuse University alum wrote best-selling novel", Syracuse.com, July 7, 2015.

- ^ "Safari West: Poems". AALBC.com.

- ^ "Negro In Literature Today". Ebony. Johnson Publishing Company. September 1963. pp. 73–76. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ Troy (July 17, 2014). "Ebony Magazine's September 1963 Issue Was Great!". AALBC. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ Bates, Karen Grigsby (July 13, 2015). "A Tribute To John Williams, The Man Who Wrote 'I Am'". NPR.org. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ Fiorelli, Julie A. (2014). "Imagination Run Riot: Apocalyptic Race-War Novels of the Late 1960s". Mediations. 28 (1): 127.

- ^ Fiorelli 2014, p. 138.

- ^ "Queenie". Opera World. Archived from the original on 2004-02-09. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Horner, Shirley. "New Jersey Q & A: John A. Williams; A Novelist's Journey in Race Relations", The New York Times, June 13, 1993. Accessed July 8, 2015. "In an interview at his home in Teaneck, Professor Williams, 67, further talked about the relationship between blacks and whites in general, and blacks and Jews in particular; his interracial marriage and the experience of teaching at Rutgers.... In 1975, the Williamses left Manhattan for Teaneck; four years later, he accepted a full-time professorship at Rutgers.... Q. How did you come to Teaneck? A. We came here because we felt the town would not be inhospitable to a mixed marriage."

- ^ "Syracuse Centennial Medal". Syracuse University. Archived from the original on July 8, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ^ a b American Booksellers Association (2013). "The American Book Awards / Before Columbus Foundation [1980–2012]". BookWeb. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

1983 ... !Click Song ... 1998 ... Safari West ... 2011 ... Lifetime Achievement.

- ^ "Lifetime Achievement Award for John A. Williams", Department of Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation, River Campus Libraries, University of Rochester.

- ^ William Grimes, "John A. Williams, 89, Dies; Underrated Novelist Who Wrote About Black Identity", The New York Times, July 6, 2015.

- ^ John A. Williams Papers. A finding aid to his papers at the University of Rochester. John A. Williams: Writings of Consequence. A digital exhibit of materials from the John A. Williams papers.

- ^ John A. Williams Papers. An inventory of his papers at Syracuse University.

- ^ "This Is My Country Too" (review), Kirkus Reviews, May 1, 1965.

Further reading

[edit]- Cash, Earl A. (1975). John A. Williams: The Evolution of a Black Writer. New York: The Third Press. ISBN 9780893881429.

- Muller, Gilbert H. (1984). John A. Williams. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0805774139.

- Tucker, Jeffrey Allen (2018). Conversations with John A. Williams. Oxford, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

External links

[edit]- "Writings of Consequence: The Art of John A. Williams". University of Rochester. Archived from the original on 2009-02-16. Retrieved 2006-07-18. Online Exhibit.

- "John A. Williams". OleMiss.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-05-30. Retrieved 2010-10-28. Writers Page.

- "John A. Williams '…arguably the finest African-American novelist of his generation'". African American Literature Book Club.

- John A. Williams papers, D.293, Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus Libraries, University of Rochester

- Black Writers in Paris, the FBI, and a Lost 1960s Classic: Rediscovering The Man Who Cried I Am (online Library of America discussion of Williams and The Man Who Cried I Am with Merve Imre, Adam Bradley, and William Maxwell, November 2023)

- 1925 births

- 2015 deaths

- 20th-century African-American writers

- 21st-century African-American writers

- African-American novelists

- American Book Award winners

- American writers

- Writers from Teaneck, New Jersey

- Syracuse University alumni

- United States Navy personnel of World War II

- Writers from Jackson, Mississippi