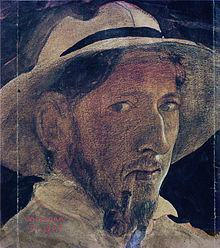

John Bauer (illustrator)

John Bauer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | John Albert Bauer 4 June 1882 |

| Died | 20 November 1918 (aged 36) Vättern, Sweden |

| Resting place | Jönköping, Sweden |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Education | Royal Swedish Academy of Arts, Stockholm |

| Known for | Illustration Painting |

| Notable work | Tuvstarr gazes into the water The Fairy Princess Saint Martin, the Holy |

| Movement | Romantic nationalism |

| Spouse | Ester Ellqvist |

| Awards | Medal of honor, 1915, San Francisco. |

John Albert Bauer (4 June 1882 – 20 November 1918) was a Swedish painter and illustrator. His paintings dealt with Swedish nature, mythical creatures, and magical places while he also composed portraits. He is best known for his illustrations in early editions of Bland tomtar och troll (Among Gnomes and Trolls), an anthology about Swedish folklore and children's fairy tales.

Bauer was born and raised in Jönköping, the son of a respected food manufacturer. At 16, he moved to Stockholm to study at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts. During his years at the academy, he received his first commissions to illustrate stories in books and magazines; he also met artist Ester Ellqvist, whom he married in 1906.

Early in his career, Bauer traveled throughout Lappland, Germany, and Italy. Influences from these cultures became vital to his works. He painted and illustrated in a romantic nationalistic style, with influences from the Italian Renaissance and Sami culture. Most of his works are watercolors or prints in either monochrome or muted colors, due to the available printing techniques of the time. His artistic expressions also included oil paintings and frescos.

Bauer was still exploring these artistic techniques when, at the age of 36, he, Ester and their son, Bengt, drowned in a shipwreck on Lake Vättern.

His illustrations and paintings broadened the understanding and appreciation of Swedish folklore, fairy tales and landscape.

Biography

Early life and education

John Bauer was born and raised in Jönköping, the son of Josef Bauer, a man of Bavarian origin, and Emma Charlotta Wadell, from a farming family from the town Rogberga just outside Jönköping.[1][2] Josef Bauer came to Sweden in 1863, penniless. He founded a successful charcuterie business at the Östra Torget in Jönköping.[2] The family lived in the apartment above the shop until 1881 when the construction of their house in Sjövik was completed.[3] John, born in 1882, lived at the Villa Sjövik by the shore of Lake Rocksjön with his parents and two brothers, one older and one younger; his only sister died at a young age.[2] The family home would remain central to him long after he lived on his own.[3][4] He had his initial schooling at the Jönköpings Högre Allmäna Läroverk (The Jönköping Public School of Higher Education),[1] followed by the Jönköpings Tekniska Skola (The Jönköping Technical School)[5] from 1892 to 1898.[1] He spent most of his time at school drawing caricatures of his teachers and daydreaming,[4] something not appreciated by his teachers.[2]

He was always given to sketching and drawing, without encouragement from his family.[2] However, when he turned sixteen and wanted to go to Stockholm to study art, they were enthusiastic for him and backed him financially.[6] In 1898, he was one of the 40 applicants to study at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts, and although he was deemed well qualified for a place at the academy, he was too young to be accepted. He spent the next two years at the Kaleb Ahltins school for painters. During this time he was, like most teenagers, torn between hope and despair, something that is reflected in his artwork.[6]

In 1900, he was finally old enough to attend the Academy of Arts, and he was one of the three students admitted that year. The other two who were accepted were his friends Ivar Kamke and Pontus Lanner.[7] At the academy he studied traditional illustrations and made studies of plants, medieval costumes and croquis; all of which benefited him in his later work illustrating Swedish folk sagas.[8] One of his teachers, professor and noted historic painter, Gustaf Cederström praised Bauer:

- His art is what I would call great art, in his almost miniaturized works he gives an impression of something much more powerful than many monumental artists can accomplice on acres of canvas. It is not size that matters but content.[9]

During his years at the academy, he received his first commissions to illustrate magazines (e.g. Söndags-Nisse and Snöflingan) and books (e.g. De gyllene böckerna, Ljungars saga and Länge, länge sedan).[10][11] In 1904, he traveled to Lappland to create paintings for a new book about the culture of the county and its "exotic wilderness".[12][13] At the end of 1905, he left the academy and put "Artist" on his business card.[14]

Journey to Lappland

With the discovery of large iron ore deposits in the north of Sweden, Lappland became a new frontier for industrial development instead of simply an exotic wilderness of the Sami culture and the midnight sun. To capitalize on this change, Carl Adam Victor Lundholm decided to publish a new illustrated book on Lappland called Lappland, det stora svenska framtidslandet (Lappland, the great Swedish land of the future).[15] He engaged noted Swedish artists—such as Karl Tirén, Alfred Thörne, Per Daniel Holm and Hjalmar Lindberg—to create the illustrations. Since Bauer was an inexperienced illustrator by comparison, Lundholm tested his abilities by sending him to create some drawings of Sami people at Skansen.[16]

Although reluctant to audition for the commission, on 15 July 1904 Bauer left for Lappland and stayed there for a month. Coming from the dense, dark forests of Småland he was overwhelmed by the open vistas and colorful landscapes. His encounters with the Sami people and their culture became important for his later works. He took many photos, sketched and made notes of the tools, costumes and objects he saw, but he had difficulty becoming close to the Sami, due to their shyness.[16] He recorded his experiences in his diary and in letters to his family and friends.[17] After a visit to a Sami goahti he noted: "All light from above. If the head is tilted forward it is dark. The lit parts of the figure always lighter than the tent canvas. Sharp shadows run like spokes from the middle of the goathi."[18]

The book on Lappland was published in 1908, and contained eleven watercolors by Bauer. He painted these in Stockholm, almost 18 months after his visit, using the photos and sketches he had collected during his journey.[19] Many of the photos resulted in other drawings and paintings. Most of these were romanticized versions of the photos, but he succeeded in capturing the nuances and ambiance of the goahtis, and the richness of the Sami garments and crafts. Details from the Sami culture, such as the bent knives, shoes, spears, pots and belts, became important elements in the clothes and ornamentations of Bauer's trolls.[17] Bauer's eye for detail and his numerous notes also made the material an ethnographic documentation of the era.[20]

Courtship and marriage

Baer met fellow student Ester Ellqvist at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts. Ellqvist studied at the separate department for women, since women were not allowed to attend the same classes as the men and their education was conducted in a different manner.[nb 1] So, while Ellqvist was talented and ambitious, she did not have an equal opportunity as her male colleagues to develop her artistry.[21]

Bauer started courting her in 1903,[22] but since they were apart most of the time, this was done by mail. Their relationship developed as they shared their dreams, aspirations, doubts and insecurities in their correspondence.[nb 2] For Bauer, Ellqvist became his inspiration, muse, and "fairy princess"; it was as such he painted her for the first time in Sagoprinsessan (The Fairy Princess). He made sketches for the painting in 1904, and finalized them in an oil painting in 1905. Ellqvist is portrayed as a strong, enlightened and unobtainable Valkyrie.[27] The painting was shown at Bauer's first exhibition at the Valand Academy in Gothenburg in 1905 (where he was one of eleven debutants)[14] and in Norrköping in 1906, where it was sold to a private collector.[28] It is now in the Jönköpings läns museum.[29] Bauer tried to mold Ellqvist into his vision of a creature of the woods and as the perfect artist's wife; he wanted her to make a home for them in a romantic cottage in the woods, while he wandered about the forest seeking inspiration.[30]

Ellqvist, on the other hand, had been raised in Stockholm and was a lively person who enjoyed the social life that could only be found in towns or cities. She wanted to settle down in a comfortable place with a husband and have children. Bauer was not sufficiently established an artist to provide for a family;[27] throughout his entire lifetime he relied on his parents for financial support. When he proposed to Ellqvist, Bauer did so without the approval of his parents, who thought that he should be more established in a career and self-supporting before marriage.[31]

On 18 December 1906, Bauer and Ellqvist were married. Not much is known about their first years together since they now lived in the same house, making letters unnecessary. Bauer had jobs illustrating covers for magazines, like Hvar 8 Dag, and began work on Bland tomtar och troll (Among Gnomes and Trolls).[32][33] In 1908, John and Ester traveled to Italy together; on their return they found a house, the "Villa Björkudden", situated on the shores of Lake Bunn just outside of Gränna. They bought the house in 1914, and the following year their son Bengt (called "Putte") was born.[34] The birth of Putte marked a harmonious and joyful time for the couple. Bauer made his final illustrations for Among Gnomes and Trolls, his grand farewell to the series, which freed him to explore playwriting and make frescos. He showed his paintings at exhibitions and experimented with modernism,[nb 3] but all this came at a cost.[35] Bauer was often away, leaving Ellqvist alone at home, and he no longer had the steady income that the illustrations had provided.[36] By 1917, their marriage was in trouble, and in 1918, Bauer put his thoughts about a divorce in a letter to his wife.[37][27]

Over time, Bauer used Ellqvist as a model less frequently.[38] With the birth of their son, Bauer started to paint pictures with children as part of the composition. The painting Rottrollen (The Root Trolls), completed in 1917, is of Putte sleeping among troll-shaped roots in a forest.[39]

Journey to Italy

When in 1908 Bauer and his wife had the opportunity to make a long journey at Josef's expense, they choose to travel through Germany and on to Italy based on his great impression of old medieval towns during a visit to Germany with his father in 1902. The couple visited Verona, Florence, Siena, and stayed two months in Volterra. They continued their journey through Naples and Capri, before spending the winter in Rome.[40]

Throughout their travels they studied art and visited churches and museums, which appealed to Bauer's eclectic mind. In the evenings they went to small tavernas to enjoy the ambiance; all of which is recorded in the letters[nb 2] they sent home to Bauer's family.[41] Bauer's sketchbooks from the journey are full of studies of antique objects and Renaissance art, some of which he later used in his illustrations. A portrait of Ghirlandaio by Sandro Botticelli is said to be the basis for Svanhamnen (The Swan maiden), and Piero della Francesca's work was the inspiration for Den helige Martin (Saint Martin, the Holy). He also became intrigued by frescoes. He was exuberant in the study of art, but he also became homesick for the quiet serenity of the Swedish forest[42] which resulted in some of his best winter pictures with white snow, dark woods and the sky glittering with tiny stars.[43]

The journey was aborted following a murder that occurred in the building where they lived in Rome. Bauer was interrogated by the Italian police due to a misunderstanding. He was never a suspect but the situation became a public sensation, leaving a bitter memory of their visit to Rome.[44]

Death on Lake Vättern

Bauer, Ester and their two-year old son, Bengt, were on their way to their new home in Stockholm, where Bauer hoped for spiritual renewal and a new life for himself and his family. A recent, well-publicized train accident at Getå[45] caused Bauer to book their return to Stockholm by boat, the Per Brahe steamer.[46]

On the night of 19 November 1918, when the steamer left Gränna it was loaded with iron stoves, plowshares, sewing machines and barrels of produce. All the cargo did not fit into the hold and a significant portion was stored unsecured on deck, making the ship top-heavy. The weather was bad and by the time the steamer was at sea a full storm was raging; the wind caused the cargo on deck to shift, some of it falling overboard, further destabilizing the ship. The ship capsized and went down, stern first, just 500 metres (1,600 feet) from the next port, Hästholmen, killing all 24 people on board, including the Bauers. Most of the passengers had been trapped in their cabins.[47]

The wreckage, found on 22 November 1918, at a depth of 32 metres (105 feet), was salvaged on 12 August 1922. Investigations indicated that only one third of the cargo had been stowed in the hold, while the rest was on deck, unsecured.[47] The salvage operation turned into a bizarre public attraction; for example, a sewing machine from the steamer was smashed into pieces and sold for one crown each. It is estimated that about 20,000 people came to watch the raising of the ship, requiring the addition of trains from Norrköping. Newsreels featuring the raising of the ship were shown in cinemas all over Sweden.[48] In order to finance the salvage operation, the Per Brahe was sent on a macabre tour throughout Sweden.[49] The newspapers fed people's superstitions that the mythical creatures of the forests had claimed Bauer by sinking the ship. The most common theme was connected to the tale Agneta och sjökungen (Agneta and the Sea King) from 1910 in which the Sea King lures a maiden into the depths.[50] On 18 August 1922, the Bauers were buried at the Östra cemetery in Jönköping (in quarter 04 plot number 06).[51]

Bauer, the person

Bauer consistently and privately doubted himself. He considered the praise he received for his pictures of trolls and princesses to be "a nice pat on the head for making funny pictures for children".[52] He wanted to paint in oil and make what he called "real art", but he needed the money he received for his illustrations.[53] His self-doubts were contrary to his public persona and the way he presented himself in self-portraits: strong and self-deprecating in his relation to the trolls and gnomes.[54][55]

Career

Subjects

Bauer's favorite subject was Swedish nature, the dense forests where the light trickled down through the tree canopies. Ever since he was little he had wandered in the dark woods of Småland imagining all the creatures living there.[56] His paintings frequently included detailed depictions of plants, mosses, lichens and mushrooms found in the Swedish woods.[57] He is best known for his illustrations of Among Gnomes and Trolls.[58]

In a 1953 article in Allers Familje-journal (Allers Family Journal), his friend Ove Eklund stated that "although [Bauer] only mumbled about and never said clearly", he believed that all the creatures he drew actually existed. Eklund had on several occasions accompanied Bauer on his walks through the forests by Lake Vättern, and Bauer's description of all the things he thought existed made Eklund feel he could see them as well.[59]

Ove Eklund on Bauer:

- Yes, there he was, John Bauer, with his brown, eternal pipe glued to the corner of his mouth. Now and then he blew a small cloud of brown troll smoke straight up into the turquoise-bleu, sun-sparkling space. And muttered something far behind his tight, narrow lips—not always so easy to decipher. But I, having had the key for many years, understood most of it.[59]

Inspiration

Bauer and his friends were part of a generation of Swedish painters who started their careers just before the Modernism movement in Europe began to flourish, but at the same time they were considerably younger than the artists still dominating the Swedish art scene: Carl Larsson, Anders Zorn and Bruno Liljefors.[21] Bauer was inspired by these artists, but also came in contact with the works of Fritz Erler, Max Klinger and other German illustrators, due to his heritage.[60] He lived in an era when the Old Norse were romanticized throughout Scandinavia, and he borrowed ideas and motifs from artists like Theodor Kittelsen and Erik Werenskiöld, yet his finished works were in his own style. [61] After his journey to Italy his works clearly showed elements from the 14th century Renaissance. The pictures of princes and princesses had elements from Flandic tapestries, and even the trolls garments were pleated, much like the draped clothing seen in antique Roman sculptures.[62]

Style

Bauer had a time consuming technique when painting: he would start with a small sketch, no bigger than a stamp, with just the basic shapes. Then he would make another, slightly bigger, sketch with more details. The sketches grew progressively in size and detail until the work reached its final size. Most of the originals for About Gnomes and Trolls are square pictures about 20 to 25 centimetres (7.9 to 9.8 inches). He doodled on anything at hand, from used stationary to the back of an envelope.[63] Many of his sketches resemble cartoon strips where the pictures get bigger and more detailed. He would also do several versions of the same finished picture, such as one where the motif is depicted in a summer and winter scene.[64][65] He did not observe the traditional hierarchy in the mediums or techniques at that time. He could make a complete work in pencil or charcoal just as well as a sketch in oil.[66]

At the beginning of his career, Bauer had to adapt his illustrations to the printing technique at that time. Full-color printing was expensive, and therefore not normally done, so the illustrations were made in one color plus black.[67] As the printing process developed and his works were in greater demand, his pictures were produced with more color until they were finally printed in full color.[68]

Watercolor

The most noted of Bauer's pictures are his watercolors, the technique he used when illustrating for books and magazines; he alternated between aquarelle and gouache. When he created illustrations the two mediums were sometimes mixed, since he needed both the speed of the aquarelle and the contrast and impasto that the gouache provided.[69] These water-soluble, and fast drying, media allowed Bauer to work on his pictures until the last minute before deadline, something he was prone to do.[70]

Among Gnomes and Trolls

In 1907, Bauer was asked by the Åhlén & Åkerlund publishing house (now Bonnier Group) to illustrate their new series of books, Among Gnomes and Trolls. The books would be published annually, and contain stories by prominent Swedish authors.[67] The majority of Bauer's pictures for the book were full page watercolor illustrations in a muted color scheme; he also contributed with covers, vignettes and other smaller illustrations.[1] Bauer's most significant creatures, the trolls, were rendered in shades of gray, green, and brown, the colors of the forests, as if these beings had grown from the landscape itself.[71]

In the 1907–10 editions, due to the printing techniques available at that time, all the pictures were reproduced in two colors: black and yellow. Some of Bauer's original paintings for these prints were in full color.[72]

In 1911, when Bauer again was asked to illustrate the book, he made it clear to the publisher that he wanted to retain his pictures along with the copyrights after publication. The publishing house had kept the original illustrations for the previous editions and considered them their property. Bauer was backed up in his request by other artists facing the same problem. The publishers did not budge from their position and without Bauer's illustrations, book sales dropped.[73]

For the 1912 edition, the publisher yielded to Bauer's demands and he was once again illustrating the book. Printing techniques had also been updated and the pictures could be printed in three colors: black, yellow and blue. With this technical improvement, the prints almost resembled Bauer's original paintings.[74]

Bauer illustrated the 1913–15 editions, printed in the same three colors as previously. 1913 marked the peak of his performance in these books, and Bauer's illustrations from that edition are among the most reproduced of his works.[75] In 1914, his illustrations started to be influenced by the Italian Renaissance. At that time Bauer wanted to stop illustrating the series, but was contractually obligated to illustrate one more edition.[76] 1915 was the last year he worked with trolls and gnomes; he said he "was done with them and wanted to move on".[77] The war in Europe had altered Bauer's vision of the world and he stated that he could no longer imagine it as a fairy tale.[78]

Tuvstarr

Ännu sitter Tuvstarr kvar och ser ner i vattnet (Still, Tuvstarr sits and gazes down into the water) ("Tuvstarr" is Swedish for Carex cespitosa), painted in 1913, is one of Bauer's most noted works.[79]

Until the 1980s, the most reproduced and publicized of Bauer's works were two paintings depicting the princess and the moose from Sagan om älgtjuren Skutt och lilla prinsessan Tuvstarr (The Tale of the Moose Hop and the Little Princess Cotton Grass), published in 1913. The first picture is of the princess riding on the moose and the second is of the moose standing guard over the sleeping princess. They were mainly used as pictures on the wall in nurseries.[80] The same tale also contains the picture of Tuvstarr gazing down into the tarn looking for her lost heart, an allegory of innocence lost.[33] Bauer made several studies of this motif.[81][82] During the 1980s the painting of Tuvstarr and the tarn was used in advertising for a shampoo. This started a debate in Sweden about how works of art, considered part of the national heritage, should be used.[33] In 1999, the picture again appeared in advertising, this time in a manipulated version in which all the trees had been cut down and Tuvstarr seemed to be lamenting them. The award-winning advertising campaign was made by the Naturskyddsföreningen (The Swedish Society for Nature Conservation) and helped further the newly awakened environmental movement in Sweden.[83] In his biography on Bauer, Gunnar Lindqvist argues that the picture has become too commercialized.[84]

Oil painting

Bauer created most of his major works in oil at the beginning of his career, since this was the traditional technique taught at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts. The trip to northern Sweden resulted in many sketches and watercolors for the Lappland book, but also in an oil on canvas entitled, Kåsovagge (1904).[19] From 1903 to 1905, he made several portraits and landscapes influenced by Expressionism.[85] He also made his first oil of Ester, The Fairy Princess, a painting with elements from the Pre-Raphaelites. This work indicates what kind of paintings Bauer wanted to do,[28] but his commissions from illustrating "Among gomes and trolls" got in the way. He wrote that he "felt like a Jack-of-all-trades", and made regular outbursts in letters to editors and publishers asking for his help, saying that he "had to work, he wanted a future painting in oil and the rest be damned".[nb 4][53] By the time he ceased painting his trolls and gnomes, he was tired and worn out and turned to other venues such as scenography, writing a compendium on drawing to be used in schools, and starting with frescos. He never got to revisit oil painting fully before he drowned.[86]

Large works

As in his earlier works at the academy, Bauer showed an interest in large frescos and, after his visit to Italy, this interest grew. His first chance to create a major work using this technique was in 1912, when he did a 1.5-by-1.5-metre (4 ft 11 in by 4 ft 11 in) fresco-secco mural, Vill-Vallareman, at the home of publisher Erik Åkerlund.[87] In 1913, he was asked to do a fresco for the Odd Fellows lodge in Nyköping, Den helige Martin (Saint Martin, the Holy).[88] At the same time, the new Stockholm Court House was under construction. Contests regarding decorations for the building were held, and most of the noted Swedish artists at that time presented entries and suggestions. Bauer made a number of sketches for these competitions, but his confidence failed and he never entered any of his drafts.[87]

Bauer's last large work was an oil painting for the auditorium at the Karlskrona flickläroverk (The Karlskrona School for Girls) in 1917. It is of Freja, the old Norse goddess of fertility. Ester posed for the painting nude and Bauer depicted her as strong, sensual and forceful.[87] Their friends teasingly called it "a breast picture of Mrs. Bauer".[88]

Exhibitions

Some of the exhibitions of his work during his lifetime were:[89]

- 1905 Gothenburg

- 1906 Norrkoping

- 1911 Rome

- 1913 Munich

- 1913 Dresden

- 1913 Brighton

- 1913 Stockholm

- 1914 Malmö

- 1915 San Francisco - Bauer was awarded the medal of honor.[1][90]

Post-humus exhibitions include:[89]

- 1934–45 Traveling exhibition

- 1968 Jönköpings läns museum, Jönköping

- 1973 Thielska galleriet, Stockholm

- 1981–82 Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

- 1993 Milesgården, Stockholm

- 1994 Göteborgs konstmuseum, Gothenburg

Collections

The Jönköpings läns museum owns over 1,000 paintings, drawings and sketches by Bauer, which is the world's largest collection of his artwork.[91] He is also represented at the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, the Gothenburg Museum of Art and the Malmö konstmuseum.[92] The John Bauer Museum in Ebenhausen, Germany is a museum dedicated to the life and works of Bauer.[93]

Works

For illustrations from the famous children's anthology, see Among Gnomes and Trolls

Other works

-

Lapplanders in snowstorm, 1904–1905, watercolor

-

Ester in the cottage, 1907, watercolor

-

Wake up Groa, wake up Mother, 1911, watercolor

-

Root trolls, 1917, pen and wash drawing

-

Portrait of an elegant lady, oil on canvas

Written work

- Bauer, John (1928). Cyrus Granér; Karl Steenberg; Gottfrid Kallstenius (eds.). Ritkurs för Sveriges barndomsskolor (in Swedish) (1–12 ed.). Stockholm: Skolboks a.-b. De förenade.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

Legacy

As of 2014[update], Bauer's pictures continue to be popular at art auctions. At Stockholm auctioneer Bukowski's classic sale in 2014, one of Bauer's gouaches, Humpe I trollskogen (Humpe in the Troll Forest), sold for 563,500 kronor (about US$87,000), and a watercolor, En riddare red fram (A Knight Rode Forth), sold for 551,250 kronor (approximately US$85,100).[94][95]

John Bauer's illustrations have been reprinted many times. His pictures are considered among the classics in fairy tales.[91] As of 2014[update], books with Bauer's pictures have been published in ten languages.[96] Bauer's works have influenced Sulamith Wülfing, Kay Nielsen, Brian Froud, Rebecca Guay, and other illustrators. In his biography on Bauer, Gunnar Lindqvist states that: "Although Bauer's work is sometimes credited to have influenced that of Arthur Rackham, and vice versa, these artists did not come in contact with each other's works until the 1910s when they had already established their own style. Any similarities must therefore be credited to their common inspirations by the romantic Munich art of the late 1800s and the art of Albrecht Dürer."[97]

In Jönköping, a memorial in honour of Bauer stands in the Town park, which was created in 1931 by Swedish sculptor Carl Hultström.[98] Hultström also made a bust in bronze of Bauer, which sits in the National Portrait Gallery at Gripsholm Castle.[99]

Celebrating John Bauer's centennial birthday in 1982, the Swedish postal service issued three stamps with motifs from Among Gnomes and Trolls. In 1997, another four were issued.[92]

A park and an adjacent street at the place where Villa Sjövik, Bauer's family home, once stood were named after him. The area is now part of the municipality of Jönköping.[100] In Mullsjö a street was named after Bauer,[101] and in Nyköping a square was named after him.[102]

The John Bauer Trail (John Bauer leden) is a hiking trail through the woods where Bauer used to wander in search of motifs and inspiration. Located between Huskvarna and Gränna, the trail is 46 km (29 mi) long and divided into a northern and the southern part.[103]

Popular culture

- In 1986, Sveriges Television produced and broadcast the movie Ester—om John Bauers wife (Ester—About John Bauers Wife). Ester was played by Lena T. Hansson, while John was portrayed by Per Mattsson.[104]

- A short film for children about Bauer and storytelling, John Bauer, fantasin och sagorna (John Bauer, Fantasy and Tales) was made in 2013; created by Ulf Hansson, Kunskapsmedia AB, in co-operation with the Jönköpings läns museum and John Bauer Art HB.[105]

- The Sveriges Television series Konstverk berättar (A Work of Art Tells a Story) featured the picture At dusk she often snuck out just to get a whiff of the good smell in the episode "The childhood picture", by Bengt Lagerkvist on 24 January 1977. The episode is available in Sweden through the Swedish Television Open Archive.[106]

- A film project about John and Ester Bauer was started in 2012, by Börje Peratt. Called John Bauer—Bergakungen (John Bauer—The Mountain King), the movie focuses on the fairy tale artist and his love for Ester. Gustaf Skarsgård is slated for the role of Bauer.[107]

- Swedish photographer Mats Andersson published a book where he revisited the forests of Bauer, using a camera instead of drawing. The pictures were also exhibited at the Abecita art museum in Borås in November 2013.[108][109]

- A Scandinavian franchise of private schools (now defunct) derived its name and some themes from Bauer, such as naming the classes after his characters.[110]

- Bauer is mentioned in Neil Gaiman's comic book series The Sandman.[111]

- The visual look of the motion picture The Dark Crystal, directed by Jim Henson and Frank Oz, was developed by primary concept artist and chief creature designer, Brian Froud, who was inspired by Bauer's art.[112]

- Italian musician Gianluca Plomitallo, a.k.a. "The Huge", made an album called John Bauer–Riddaren Rider, in which all the songs are named after pictures by Bauer.[113]

- Norwegian Artist Mortiis uses the art of Bauer on his ambient albums.[114]

- Swedish poet Roger L. Svensson recalls the Bauer Memorial and Bauer's creations in his poems.[115]

Notes

- ^ e.g. When they did croquis, the models were not allowed to remove all of their clothing.

- ^ a b Most of the correspondence attributed to John Bauer (about 1000 letters) is now in the Jönköpings läns museum.[23] The letters in the collection are in the process of being digitized.[24] Other letters to and from Bauer can be found at the National Library of Sweden[25] and the Gothenburg University Library[26]

- ^ This experimentation can be seen in the gouache Fanstyg (Devilry), where he mocked figures from his earlier paintings in distorted blue shapes and Blå Eva (Blue Eve), a dreamlike tempera of Eve in blue shades painted in 1918.

- ^ Bauer did not consider the illustrations he made to be (real) work, as opposed to oil paintings, just trifles he received money for doing.

References

- ^ a b c d e Romdahl, Axel L. "John Bauer". In Axelsson, Roger (ed.). Svenskt biografiskt lexikon (in Swedish). Vol. 2 (1920 ed.). Stockholm: National Archives of Sweden. p. 783. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Den unge Bauer". www.jkpglm.se. Jönköpings läns museum. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Villa Sjövik". www.jkpglm.se. Jönköpings Läns Museum. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ a b Agrenius 1996, p. 8.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 9.

- ^ a b Corin 2013, p. 8.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 10.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 12.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 13.

- ^ Wahlenberg & Bauer 1903.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 14.

- ^ Bjurström et al. 1982, p. 190.

- ^ a b Corin 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Agrenius 1996, p. 23.

- ^ a b Lindqvist 1979, p. 16.

- ^ a b Corin 2013, p. 14.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 21.

- ^ a b Bjurström et al. 1982, p. 14.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 20.

- ^ a b "Konstakademien". www.jkpglm.se. Jönköpings Läns Museum. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 32.

- ^ "Lär känna John Bauer i ny utställning på Länsmuseet". www.jnytt.se. Jnytt.se. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Rossler, Magnus. "Digitalisering av John Bauers brevsamling". www.jkglm.se. Jönköpings läns museums. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Corin 2013, p. 60.

- ^ "Brev till konstnären John Bauer" (PDF). www.ub.gu.se. Gothenburg University Library. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "John & Ester". www.jkpglm.se. Jönköpings Läns Museum. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ a b Agrenius 1996, p. 26.

- ^ "Sagoprinsessan (Oljemålning)". www.digitaltmuseum.se. Digitalt Museum. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Lindqvist 1979, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Agrenius 1996, p. 29.

- ^ Corin 2013, pp. 18–20.

- ^ a b c Huss, Pia. "Fast i sagans värld". www.lararnasnyheter.se/. Swedish Teachers' Union. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Corin 2013, p. 40.

- ^ "Nya vägar". www.jkpglm.se. Jönköpings läns museum. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Corin 2013, pp. 40–42.

- ^ Corin 2013, p. 44.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 34.

- ^ Bjurström et al. 1982, p. 174.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 38.

- ^ Agrenius 1996, p. 35.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Corin 2013, p. 22.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 39.

- ^ "Getåolyckan 1918" (in Swedish). Retrieved July 23, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Lindqvist 1979, pp. 85–88.

- ^ a b Bergquist, Lars (1980). Per Brahes undergång och bärgning. Stockholm: Norstedt. ISBN 91-1-801012-1. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Extratåg sattes in - alla ville se bärgningen". www.svd.se. Svenska Dagbladet. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Pengar samlades in på makaber "turné"". www.svd.se. Svenska Dagbladet. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Olenius 1966, pp. 86–87.

- ^ "Historiska och kända personer begravda på Östra kyrkogården". www.svenskakyrkanjonkoping.se. Svenska kyrkan Jönköping. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Bjurström et al. 1982, p. 26.

- ^ a b Bjurström et al. 1982, p. 18.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, pp. 27–78.

- ^ Bjurström et al. 1982, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Agrenius 1996, pp. 30–33.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, pp. 24–26.

- ^ "Konstnären John Bauer – biografi". www.jkpglm.se. Jönköpings Läns Museum. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Eklund, Ove (1953). "Bergakungens sal". Allers Familje-journal: 14–16.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 90.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Agrenius 1996, pp. 38–41.

- ^ "Arbetsmetod". www.jkpglm.se. Jönköpings Läns Museum. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Agrenius 1996, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, pp. 40–43.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, pp. 27–50.

- ^ a b Corin 2013, p. 20.

- ^ Corin 2013, pp. 30–ff.

- ^ Bjurström et al. 1982, pp. 67–110.

- ^ Agrenius 1996, p. 41.

- ^ Bjurström et al. 1982, p. 36.

- ^ Corin 2013, pp. 20–27.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, pp. 52.

- ^ Corin 2013, p. 30.

- ^ Corin 2013, p. 34.

- ^ Corin 2013, p. 36.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 65.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Agrenius 1996, p. 45.

- ^ Petri, Gunilla (21 April 1980). "Vår barndoms trollvärld". Barometern: 2.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Agrenius 1996, pp. 41–45.

- ^ Bauer, John (1931). John Bauers bästa: ett urval sagor ur Bland tomtar och troll åren 1907–1915. Stockholm: Åhlén & Åkerlund.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Ottosson, Mats. "Upp till kamp för trollen". www.naturskyddsforeningen.se. Naturskyddsföreningen. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 58.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 28.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, pp. 66–86.

- ^ a b c Lindqvist 1979, pp. 74–77.

- ^ a b "Monumentalkonsten". www.jkpglm.se. Jönköpings Läns Museum. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Agrenius 1996, p. 72.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, p. 78.

- ^ a b Lindqvist 1979, pp. 7.

- ^ a b "Konstnärslexikonett Amanda". www.lexikonettamanda.se. Kultur1. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "John Bauer Museum in Ebenhausen". www.oerlenbach.rhoen-saale.net. Gemeinde Oerlenbach. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "590. John Bauer, Humpe i trollskogen". www.bukowskis.com. Bukowskis. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "641. John Bauer, En riddare red fram". www.bukowskis.com. Bukowskis. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "John Bauer". www.libris.se. LIBRIS–Nationella bibliotekssystem. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ Lindqvist 1979, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Leimola, Jimmie; Andersson, Anna. "Statyspecial: John Bauer". www.jnytt.se. Jnytt.se. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Malmborg, Boo von (1951–1952). Katalog över statens porträttsamling på Gripsholm. Stockholm. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "John Bauers Park". www.jonkoping.se. Jönköping Municipality. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Friluftsriket Mullsjö" (PDF). www.mymap.se. Infabvitamin AB. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Parkprogram för Nyköpings stadskärna. Bilaga: Namn på parker" (PDF). www.nykoping.se. Nyköping Municipality. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "John Bauerleden". www.jonkoping.se. Jönköping Municipality. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ester - om John Bauers hustru (1986)". www.sfi.se. Swedish Film Institute. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "John Bauer, fantasin och sagorna". www.kunskapsmedia.se. Kunskapsmedia. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Lagerkvist, Bengt. "Konstverk berättar, Barndomens bild". www.oppetarkiv.se. Sveriges Television. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "John Bauer–Bergakungen". http://johnbauerfilm.wordpress.com/. John Bauer Film. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website=|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Marjavaara, Nina. "Mats Andersson tolkar Bauer på Abecita". www.jonkopingsposten.se. Jönköpings-Posten. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tidigare fotokvällar". www.abecitakonst.se. Abecita konstmuseum. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Söderberg, Kjell. "John Bauer avvecklas – har gjort miljonklipp". www.flamman.se. Flamman. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Bender, Hy (2000). The Sandman companion. London: Titan. ISBN 1-84023-150-5. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Jim Henson's the Dark Crystal". www.darkcrystal.com. The Jim Henson Company. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "John Bauer - Riddaren Rider". http://thehuge.bandcamp.com/. Bandcamp. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website=|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Mortiis". www.mortiis.com. Mortiis. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ Svensson, Roger L. "Regn över Bauermonumentet". www.poeter.se. Poeter.se. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

- Bibliography

- Agrenius, Helen (1996). Om konstnären John Bauer och hans värld (in Swedish). Jönköping: Jönköpings läns museum. ISBN 91-85692-29-8. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

- Bjurström, Per; Lindqvist, Gunnar; Börtz-Laine, Agneta; Holmberg, Hans (1982). John Bauer: en konstnär och hans sagovärld (in Swedish). Höganäs: Bra Böcker i samarbete med Nationalmus. ISBN 91-38-90217-6. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

- Corin, Claes (2013). I John Bauers fotspår (in Swedish). Laholm: Corzima. ISBN 978-91-637-3020-7. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

- Lindqvist, Gunnar (1979). John Bauer (in Swedish). Stockholm: Liber Förlag. ISBN 91-38-04605-9. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Olenius, Elsa, ed. (1966). John Bauers sagovärld: en vandring bland tomtar och troll, riddare och prinsessor tillsammans med några av våra främsta sagodiktare (in Swedish). Stockholm: Bonnier. ISBN 91-0-030396-8. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

- Wahlenberg, Anne; Bauer, John (1903). Länge, länge sedan ... (in Swedish). Project Runeberg.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

Further reading

- Agrenius, Helen; Jackson, Charlotte (1996). The artist John Bauer and his world. Jönköping: Jönköping County Museum. ISBN 91-85692-30-1. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help)

- Andersson, Mats; Söderlind, David (2011). John Bauers skogar (in Swedish). Jönköping: Concrete. ISBN 978-91-633-8501-8. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

- Dahlin, Eva, ed. (2009). John Bauers förtrollande sagovärld (in Swedish). Stockholm: Bonnier Carlsen. ISBN 978-91-638-6333-2. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

- Dahlin, Eva; Daniela Villa, eds. (2002). John Bauers sagovärld, för länge, länge sedan (in Swedish). Stockholm: Bonnier Carlsen. ISBN 91-638-2441-8. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

- John Bauers bästa, ett urval sagor ur Bland tomtar och troll (in Swedish). Stockholm: Åhlén % Åkerlund. 1931. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

- Lindqvist, Gunnar (1991). John och Ester, makarna Bauers konst och liv (in Swedish). Stockholm: Carlsson. ISBN 91-7798-458-7. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

- Lundburgh, Holger (2004). Swedish folk tales. Edinburgh: Floris. ISBN 0-86315-457-3. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help)

- Nilsson, Anna (1999). John Bauer, Bland tomtar och troll (in Swedish). Umeå: Institutionen för konstvetenskap. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

- Nordström, Lillemor (2000). Första boken om John Bauer. Första boken om ... (in Swedish). Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. ISBN 91-21-17954-9. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

- Olenius, Elsa, ed. (1973). Great Swedish fairy tales. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-5022-X. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help)

- Rudström, Lennart; Jones, Olive (1978). In the troll wood. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-416-86310-8. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help)

- Schiller, Harald (1935). John Bauer, sagotecknaren. Sveriges allmänna konstförenings publikation (in Swedish). Stockholm: Sveriges allmänna konstförening. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

External links

- Art Signature Dictionary - signatures and monograms 20 examples of genuine signatures and monograms by John Bauer.

- John Bauer Museum Template:Sv icon

- Pictures by John Bauer at Project Runeberg Template:Sv icon

- 11 Illustrations from Die Göttersage der Väter (1911)