.40 S&W

| .40 S&W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

An unfired hollow point .40 S&W cartridge and an expanded hollow point bullet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Pistol | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Place of origin | United States | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Production history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Designer | Smith & Wesson | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Designed | January 17, 1990 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Produced | 1990–present | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Specifications | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent case | 10mm Auto | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Case type | Rimless, Straight | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bullet diameter | .400 in (10.2 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Neck diameter | .423 in (10.7 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shoulder diameter | .423 in (10.7 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Base diameter | .424 in (10.8 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rim diameter | .424 in (10.8 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rim thickness | .055 in (1.4 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Case length | .850 in (21.6 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overall length | 1.135 in (28.8 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Case capacity | 19.3 gr H2O (1.25 cm3) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rifling twist | 1 in 16 in. (406 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Primer type | Small Pistol | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maximum pressure | 35,000 psi (240 MPa) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ballistic performance | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test barrel length: 100 millimetres (4 in) Source(s): [1][2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

The .40 S&W (10×22mm Smith & Wesson) is a rimless pistol cartridge developed jointly by major American firearms manufacturers Smith & Wesson and Winchester.[3] The .40 S&W was developed from the ground up as a law enforcement cartridge designed to duplicate performance of the Federal Bureau of Investigation's reduced-velocity 10mm Auto cartridge which could be retrofitted into medium-frame (9mm size) automatic handguns. It uses 10.16-millimetre (0.4 in) diameter bullets ranging in weight from 6.8 to 13.0 grams (105 to 200 gr).[4]

History

In the aftermath of the 1986 FBI Miami shootout, the FBI started the process of testing 9mm and .45 ACP ammunition in preparation to replace its standard issue revolver with a semi-automatic pistol. The semi-automatic pistol offered two advantages over the revolver: 1) it offered increased ammunition capacity, and 2) it was easier to reload during a firefight. The FBI was satisfied with the performance of its .38 Special +P 10.2 g (158 gr) L.S.W.C.H.P. (lead semi-wadcutter hollowpoint) cartridge ("FBI Load") based on decades of dependable performance. Ammunition for the new semi-automatic pistol had to deliver terminal performance equal or superior to the .38 Special FBI Load. The FBI developed a series of practically oriented tests involving eight test events that reasonably represented the kinds of situations that FBI agents commonly encounter in shooting incidents.

During tests of the 9mm and .45 ACP ammunition, the FBI Firearms Training Unit's Special Agent-in-Charge John Hall decided to include tests of the 10mm cartridge, supplying his personally owned Colt Delta Elite 10mm semi-automatic, and personally handloaded ammunition. The FBI's tests revealed that a 11.0–11.7 g (170–180 gr) JHP 10mm bullet, propelled between 270–300 m/s (900–1,000 ft/s), achieved desired terminal performance without the heavy recoil associated with conventional 10mm ammunition (400–430 m/s (1,300–1,400 ft/s)). The FBI contacted Smith & Wesson and requested it to design a handgun to FBI specifications, based on the existing large-frame S&W Model 4506 .45 ACP handgun, that would reliably function with the FBI's reduced velocity 10mm ammunition. During this collaboration with the FBI, S&W realized that downsizing the 10mm full power to meet the FBI medium velocity specification meant less powder and more airspace in the case. They found that by removing the airspace they could shorten the 10 mm case enough to fit within their medium-frame 9mm handguns and load it with a 11.7 g (180 gr) JHP bullet to produce ballistic performance identical to the FBI's reduced velocity 10mm cartridge. S&W then teamed with Winchester to produce a new cartridge, the .40 S&W. It uses a small pistol primer whereas the 10mm cartridge uses a large pistol primer.

The .40 S&W cartridge debuted January 17, 1990, along with the new Smith & Wesson Model 4006 pistol, although it was several months before the pistols were available for purchase. Austrian manufacturer Glock Ges.m.b.H. beat Smith & Wesson to the dealer shelves in 1990, with pistols chambered in .40 S&W (the Glock 22 and Glock 23) which were announced a week before the 4006.[5] Glock's rapid introduction was aided by its engineering of a pistol chambered in 10mm Auto, the Glock 20, only a short time earlier. Since the .40 S&W uses the same bore diameter and case head as the 10mm Auto, it was merely a matter of adapting the 10mm design to the shorter 9×19mm Parabellum frames. The new guns and ammunition were an immediate success.[6][7]

The .40 S&W case length and overall cartridge length are shortened, but other dimensions except case web and wall thickness remain identical to the 10mm Auto. Both cartridges headspace on the mouth of the case. Thus in a semi-auto they are not interchangeable. Fired from a 10mm semi-auto, the .40 Smith & Wesson cartridge will headspace on the extractor and the bullet will jump a 3.6 millimetres (0.142 in) freebore just like a .38 Special fired from a .357 Magnum pistol. If the cartridge is not held by the extractor, the chances for a ruptured primer are great.[8] Smith and Wesson does make a double action revolver that can fire either at will using moon clips. A single-action revolver in the .38–40 chambering can also be modified to fire the .40 or the 10 mm if it has an extra cylinder. Some .40 caliber handguns can be converted to 9mm with a special purpose made barrel, magazine change, and other parts.[9][10]

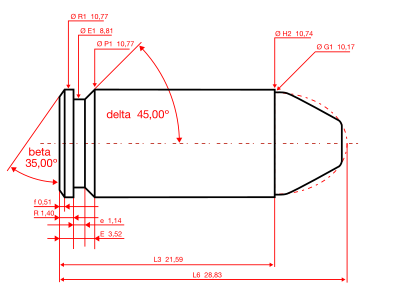

Cartridge dimensions

The .40 S&W has 1.25 ml (19.3 grains H2O) cartridge case capacity.

.40 S&W maximum C.I.P. cartridge dimensions.[2] All sizes in millimeters (mm).

The common rifling twist rate for this cartridge is 406 mm (1 in 16 in), 6 grooves, ∅ lands = 9.91 mm, ∅ grooves = 10.17 mm, land width = 3.05 mm and the primer type is small pistol.[4] According to the official C.I.P. (Commission Internationale Permanente Pour L'Epreuve Des Armes A Feu Portative) guidelines the .40 S&W case can handle up to 225 MPa (32,633 psi) piezo pressure. In C.I.P. regulated countries every pistol cartridge combo has to be proofed at 130% of this maximum C.I.P. pressure to certify for sale to consumers.

The S.A.A.M.I. pressure limit for the .40 S&W is set at 241.32 MPa (35,000 psi), piezo pressure.[11]

Performance

The .40 S&W cartridge has been popular with law enforcement agencies in the United States, Canada, and Australia. While possessing nearly identical accuracy,[12] drift and drop, it has an energy advantage over the 9×19mm Parabellum, and with a more manageable recoil than the 10 mm Auto cartridge.[6] Marshall & Sanow (and other hydrostatic shock proponents) contend that with good JHP bullets, the more energetic loads for the .40 S&W can also create hydrostatic shock in human-sized living targets.[13][14]

Based on ideal terminal ballistic performance in ordnance gelatin during lab testing in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the .40 S&W earned status as "the ideal cartridge for personal defense and law enforcement".[7][15] Apart from the imperfect relationship between ordnance gelatin ballistics and actual stopping power, critics pointed to the reduced power of the round compared with the 10 mm Auto it was based on. Ballistically the .40 S&W is almost identical to the .38-40 Winchester introduced in 1874, as they share the same bullet diameter, bullet weight, and similar muzzle velocity.[16] The energy of the .40 S&W exceeds standard-pressure .45 ACP loadings, generating between 470 joules (350 ft⋅lb) and 680 joules (500 ft⋅lb) of energy, depending on bullet weight. Both the .40 S&W and the 9 mm Parabellum operate at a 240 megapascals (35,000 psi) SAAMI maximum, compared to a 140 megapascals (21,000 psi) maximum for .45 ACP.[17]

.40 S&W pistols with standard (not extended) double-stack magazines can hold as many as 16 cartridges, such as the .40 S&W versions of the Springfield Armory XDM (except for the compact models). While not displacing the 9 mm Parabellum, the .40 S&W is commonly used in law enforcement applications in keeping with its origin with the FBI. Select U.S. special operations units have available the .40 S&W and .45 ACP for their pistols. The United States Coast Guard, having dual duties as maritime law enforcement and military deployments, has adopted the SIG Sauer P229R DAK in .40 S&W as their standard sidearm.

The .40 S&W was originally loaded at subsonic velocity (around 300 m/s (980 ft/s)) with a 11.7 grams (180 gr) bullet.[15] Since its introduction, various loads have been created, with the majority being either 155, 165 or 180 gr (10.0, 10.7 or 11.7 g).[18] However, there are some bullets with weights as light as 8.7 g (135 gr) and as heavy as 13.0 g (200 gr).[7] Cor-Bon and Winchester both offer a 8.7 g (135 gr) JHP and Cor-Bon also offers a 9.1 g (140 gr) Barnes XPB hollow-point. Double Tap Ammo, based out of Cedar City, Utah loads a 8.7 g (135 gr) Nosler JHP, a 10.0 g (155 gr), 10.7 g (165 gr) and 11.7 g (180 gr) Speer Gold Dot hollow-point (marketed as "Bonded Defense"), a 11.7 g (180 gr) Hornady XTP JHP, and three different 13.0 g (200 gr) loads included a 13 g (200 gr) Full Metal Jacket (FMJ), a 13 g (200 gr) Hornady XTP JHP and Double Tap's own 13 g (200 gr) WFNGC (Wide Flat Nose Gas Check) hard cast lead bullet; the latter specifically designed for hunting and woods carry applications.[19]

Case failure reports

The .40 S&W has been noted in a number of cartridge case failures, particularly in older Glock pistols due to the relatively large area of unsupported case head in those barrels, given its high working pressure.[20][21] The feed ramp on the Glock .40 S&W pistols is larger than on other Glocks, which leaves the rear bottom of the case unsupported, and it is in this unsupported area that the cases fail. Most, but not all, of the failures have occurred with reloaded or remanufactured ammunition.[22] Cartridges loaded at or above the SAAMI pressure, or slightly oversized cases which fire slightly out of battery are often considered to be the cause of these failures.[22] These failures are commonly referred to as "kaBooms" or "kB!" for short.[22] While these case failures do not often injure the person holding the pistol, the venting of high pressure gas tends to eject the magazine out of the magazine well in a spectacular fashion, and usually destroys the pistol. In some cases, the barrel will also fail, blowing the top of the chamber off.

While the .40 S&W is far from being the only cartridge to suffer from case failures, it is more susceptible for a number of reasons. The .40 S&W works at relatively high pressures 230 MPa (33,000 psi) typical, but 240 MPa (35,000 psi) SAAMI max. Since the .40 S&W is a wide cartridge for its length, and is often adapted to frames designed for the equally long but narrower 9x19mm cartridge, the length of the feed ramp must be longer to provide the same angle, which causes the feed ramp to extend into the chamber. This in turn leaves more of the case head unsupported, reducing the margin of safety. When exacerbated by out of battery firing (leaving even more case head exposed) and potentially weakened brass (due to reloading) these factors appear to lead to the higher incidents of chamber failure. The number of case failures in the .40 S&W is serious enough that Accurate Arms no longer recommends reloading of .40 S&W cartridges for firearms without complete case head support.[23]

In late 1995, Federal Cartridge of Anoka, Minnesota undertook a redesign of their .40 S&W cartridge case to strengthen internally the area of the case web. While no one at Federal will address this for the record, it has been suggested that this move was dictated by the popularity of the .40 S&W Glocks, and Federal's attempt to hedge against head/web ruptures with any of their .40 S&W ammunition.

Federal .40 S&W rounds which may contain suspect casings may be identified as follows: Lot number consists of 10 characters (mostly numbers). In the 7th position, there may be a number or a letter. If there is a number in that position, the ammunition was manufactured with the old style (possibly defective) brass. If it contains the letter Y (1995) or R (1996), the ammunition has the redesigned casing and should be okay. If the letter H appears, then check the next three digits (the last three in the lot number). Ammunition lot numbers H244 or below have the old style casings. Lots H245 and above have the new style casings.

This information was provided by Federal Cartridge Company in September 1996.

Writer Walt Rauch first brought forth information that bullet set-back (such as often occurs in administrative unloading/loading) in the .40 S&W could raise pressures exponentially. Rauch published some specific information on this set-back issue in the May/June 2004 Police and Security News, in a feature entitled Why Guns Blow Up!: "The simple chambering and rechambering of a cartridge does push the bullet back into its case."

Hirtenberger Ammunition Company of Austria (at the request of GLOCK, Inc.) determined that, with a .40 caliber cartridge, pushing the bullet back into the case 2.5 millimetres (1⁄10 in) doubled the chamber pressure. This is higher than a proof load. This can occur with but one chambering since it is dependent on how well the case was crimped or sealed to the bullet.

Synonyms

- .40

- .40 Smith

- .40 S&W

- .40 Auto

- .40 caliber or "Forty cal"

- .40 AH

- .40 Liberty (or .40 Lib)

- .40 Short Bus

- 10x22 mm

- 10 mm Short

- 10 mm Kurz

See also

References

- ^ Midway USA page C.I.P.

- ^ a b "C.I.P. decisions, texts and tables – free current C.I.P. CD-ROM version download (ZIP and RAR format)". Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ^ "Taffin Tests: The .40 S&W". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ a b Hornady Handbook of Cartridge Reloading, Fourth Edition (1991), pp. 593–595

- ^ Petty, Charles E. (2005). "The .40 Smith & Wesson: this round came along at the right time in the right place". Guns Magazine. Archived from the original on September 13, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ a b Speer Reloading Manual Number 12 (1994) pp. 534–542.

- ^ a b c Nosler Reloading Guide Number Four (1996) pp. 529–534. Cite error: The named reference "Nosler" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Street Stoppers, E. Marshall and E. Sanow, Paladin (1996) p. 118

- ^ Petty, Charles E. (2002). "Smith & wesson model compact: Good looking and great shooting, petty finds that there is a lot to like about this new offering from the S&W performance center". Guns Magazine. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ Petty, Charles E. (2005). "Gossip, finger-pointing and whispers". American Handgunner. Archived from the original on October 8, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ "SAAMI Pressures". Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved November 29, 2007.

- ^ "New Life For An Old Cat (Stoeger Model 8000 Cougar)". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ Hollow-point ammunition and handguns: The potential for large temporary cavities, Fernando Spencer Netto, Dylan Pannell, Homer C. Tien, Injury Extra (2008) 39, 50–52.

- ^ Street Stoppers, E. Marshall and E. Sanow, Paladin (1996) pp. 25–58.

- ^ a b Marshall and Sanow, Street Stoppers, Paladin (1996) pp. 115–131.

- ^ By chuck (February 25, 2010). "Ten-X Cowboy Ammo 38-40 WCF 180 Grain Lead Round Nose Flat Point Box". Midwayusa.com. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ "SAAMI Pressure specifications". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ Stopping Power, E. Marshall and E. Sanow, Paladin (2001), pp. 49–58.

- ^ "DoubleTap Ammunition". Doubletapammo.com. July 24, 2004. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ ".40 S&W Case Failures in Glocks". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ Towsley, Bryce (June 24, 2009). "Fixing the Glock 40 S&W Bulge". Gun Digest. Archived from the original on July 23, 2010. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Glock kB! FAQ". Gun Zone. The Gun Zone. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved July 3, 2011.

- ^ "Safety". Accurate Arms.