Stegosaurus

| Stegosaurus Temporal range: Late Jurassic,

| |

|---|---|

| |

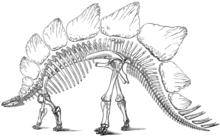

| Reconstructed S. stenops skeleton, Senckenberg Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Thyreophora |

| Clade: | †Stegosauria |

| Family: | †Stegosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Stegosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Stegosaurus Marsh, 1877 |

| Type species | |

| †Stegosaurus armatus Marsh, 1877

| |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Stegosaurus (/ˌstɛɡ[invalid input: 'ɵ']ˈsɔːrəs/, meaning "roof lizard" or "covered lizard" in reference to its bony plates[1]) is a genus of armored stegosaurid dinosaur. They lived during the Late Jurassic period (Kimmeridgian to early Tithonian), some 155 to 150 million years ago in what is now western North America. In 2006, a specimen of Stegosaurus was announced from Portugal, showing that they were present in Europe as well.[2] Due to its distinctive tail spikes and plates, Stegosaurus is one of the most recognizable dinosaurs. At least three species have been identified in the upper Morrison Formation and are known from the remains of about 80 individuals.[3]

A large, heavily built, herbivorous quadruped, Stegosaurus had a distinctive and unusual posture, with a heavily rounded back, short forelimbs, head held low to the ground and a stiffened tail held high in the air. Its array of plates and spikes has been the subject of much speculation. The spikes were most likely used for defense, while the plates have also been proposed as a defensive mechanism, as well as having display and thermoregulatory functions. Stegosaurus had a relatively low brain-to-body mass ratio. It had a short neck and small head, meaning it most likely ate low-lying bushes and shrubs. It was the largest of all the stegosaurians (bigger than genera such as Kentrosaurus and Huayangosaurus) and, although roughly bus-sized, it nonetheless shared many anatomical features (including the tail spines and plates) with the other stegosaurian genera.

Description

The quadrupedal Stegosaurus is one of the most easily identifiable dinosaur genera, due to the distinctive double row of kite-shaped plates rising vertically along the rounded back and the two pairs of long spikes extending horizontally near the end of the tail. Although large animals at up to 9 metres (30 ft) in length,[4] the various species of Stegosaurus were dwarfed by their contemporaries, the giant sauropods. Some form of armor appears to have been necessary, as Stegosaurus species coexisted with large predatory theropod dinosaurs, such as Allosaurus and Ceratosaurus.

The hind feet each had three short toes, while each forefoot had five toes; only the inner two toes had a blunt hoof. The phalangeal formula is 2-2-2-2-1, meaning that the innermost finger of the forelimb has two bones, the next has two, etc.[5] All four limbs were supported by pads behind the toes.[6] The forelimbs were much shorter than the stocky hindlimbs, which resulted in an unusual posture. The tail appears to have been held well clear of the ground, while the head of Stegosaurus was positioned relatively low down, probably no higher than 1 meter (3.3 ft) above the ground.[7]

The long and narrow skull was small in proportion to the body. It had a small antorbital fenestra, the hole between the nose and eye common to most archosaurs, including modern birds, though lost in extant crocodylians. The skull's low position suggests that Stegosaurus may have been a browser of low-growing vegetation. This interpretation is supported by the absence of front teeth and their replacement by a horny beak or rhamphotheca. Stegosaurian teeth were small, triangular and flat; wear facets show that they did grind their food. The inset placement in the jaws suggests that Stegosaurus had cheeks to keep food in their mouths while they chewed.[8]

Despite the animal's overall size, the braincase of Stegosaurus was small, being no larger than that of a dog. A well-preserved Stegosaurus braincase allowed Othniel Charles Marsh to obtain in the 1880s a cast of the brain cavity or endocast of the animal, which gave an indication of the brain size. The endocast showed that the brain was indeed very small, maybe the smallest among the dinosaurs. The fact that an animal weighing over 4.5 metric tons (5 short tons) could have a brain of no more than 80 grams (2.8 oz) contributed to the popular old idea that all dinosaurs were unintelligent, an idea now largely rejected.[9] Actual brain anatomy in Stegosaurus is poorly known, but the brain itself was however small even for a dinosaur, fitting well with a slow herbivorous lifestyle and limited behavioural complexity.[10]

Most of the information known about Stegosaurus comes from the remains of mature animals; however more recently juvenile remains of Stegosaurus have been found. One sub-adult specimen, discovered in 1994 in Wyoming, is 4.6 meters (15 ft) long and 2 meters (7 ft) high, and is estimated to have weighed 2.3 metric tons (2.6 short tons) while alive. It is on display in the University of Wyoming Geological Museum.[11] Even smaller skeletons, 210 centimeters (6.9 ft) long and 80 centimeters (2.6 ft) tall at the back, are on display at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science.

Classification

Stegosaurus was the first-named genus of the family Stegosauridae. It is the type genus that gives its name to the family. Stegosauridae is one of two families within the infraorder Stegosauria, with the other being Huayangosauridae. Stegosauria lies within the Thyreophora, or armored dinosaurs, a suborder which also includes the more diverse ankylosaurs. The stegosaurs were a clade of animals similar in appearance, posture and shape that mainly differed in their array of spikes and plates. Among the closest relatives to Stegosaurus are Wuerhosaurus from China and Kentrosaurus from east Africa.

The following cladogram shows the position of Stegosaurus within the Stegosauridae according to Mateus, 2009:[12]

Origins

The origin of Stegosaurus is uncertain, as few remains of basal stegosaurs and their ancestors are known. Recently, stegosaurids have been shown to be present in the lower Morrison Formation, existing several million years before the occurrence of Stegosaurus itself, with the discovery of the related Hesperosaurus from the early Kimmeridgian.[13] The earliest stegosaurid (the genus Lexovisaurus) is known from the Oxford Clay Formation of England and France, giving it an age of early to middle Callovian.

The earlier and more basal genus Huayangosaurus from the Middle Jurassic of China (some 165 million years ago) predates Stegosaurus by 20 million years and is the only genus in the family Huayangosauridae. Earlier still is Scelidosaurus, from Early Jurassic England, which lived approximately 190 million years ago. Interestingly, it possessed features of both stegosaurs and ankylosaurs. Emausaurus from Germany was another small quadruped, while Scutellosaurus from Arizona in the USA was an even earlier genus and was facultatively bipedal. These small, lightly armored dinosaurs were closely related to the direct ancestor of both stegosaurs and ankylosaurs. A trackway of a possible early armored dinosaur, from around 195 million years ago, has been found in France.[14]

Discovery and species

Stegosaurus, one of the many dinosaurs first collected and described in the Bone Wars, was originally named by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1877,[15] from remains recovered north of Morrison, Colorado. These first bones became the holotype of Stegosaurus armatus. Marsh initially believed the remains were from an aquatic turtle-like animal, and the basis for its scientific name, 'roof(ed) lizard' was due to his early belief that the plates lay flat over the animal's back, overlapping like the shingles (tiles) on a roof. A wealth of Stegosaurus material was recovered over the next few years and Marsh published several papers on the genus. Initially, several species were described. However, many of these have since been considered to be invalid or synonymous with existing species,[16] leaving two well-known and one poorly known species. Confirmed Stegosaurus remains have been found in the Morrison Formation's stratigraphic zones 2–6, with additional remains possibly referrable to Stegosaurus recovered from stratigraphic zone 1.[17]

Valid species

- Stegosaurus armatus, meaning "armored roof lizard", was the first species to be found and is known from two partial skeletons, two partial skulls and at least thirty fragmentary individuals.[15] This species had four horizontal tail spikes and relatively small plates. At 9 meters (30 ft), it was the longest species within the genus Stegosaurus. It has been found in the Morrison Formation, Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah, U.S.A.[18]

- Stegosaurus ungulatus, meaning "hoofed roof lizard", was named by Marsh in 1879, from remains recovered at Como Bluff, Wyoming.[19] It might be synonymous of S. armatus,[20] although the original material of S. armatus is yet to be fully described. The specimen discovered in Portugal and dating from the upper Kimmeridgian-lower Tithonian stage has been ascribed to this species.[2]

- Stegosaurus sulcatus, meaning "furrowed roof lizard" was described by Marsh in 1887 based on a partial skeleton.[21] It has traditionally been considered a synonym of S. armatus,[20] though more recent studies suggest it is in fact distinct. A spike associated with the type specimen, originally thought to be a tail spike, may in fact come from the shoulder.[22]

- Stegosaurus stenops, meaning "narrow-faced roof lizard", was named by Marsh in 1887,[21] with the holotype having been collected by Marshal Felch at Garden Park, north of Cañon City, Colorado, in 1886. This is the best-known species of Stegosaurus, mainly because its remains include at least one complete articulated skeleton. It had large, broad plates and four tail spikes. Stegosaurus stenops is known from at least 50 partial skeletons of adults and juveniles, one complete skull and four partial skulls. It was shorter than S. armatus, at 7 meters (23 ft). Found in the Morrison Formation, Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah, U.S.A.[18]

Susannah Maidment and colleagues in 2008 proposed extensive alterations to the taxonomy of Stegosaurus. They advocated synonymizing S. stenops and S. ungulatus (sometimes considered valid; see below) with S. armatus, and sinking Hesperosaurus and Wuerhosaurus into Stegosaurus, with their type species becoming Stegosaurus mjosi and Stegosaurus homheni, respectively. They regarded S. longispinus as dubious. Thus, their conception of Stegosaurus would include three valid species (S. armatus, S. homheni, and S. mjosi) and would range from the Late Jurassic of North America and Europe to the Early Cretaceous of Asia.[23] However, this classification scheme has not generally been followed by other researchers. Galton, for example, has stated that Wuerhosaurus differs enough from Stegosaurus to be retained as a distinct genus.[22]

Nomina dubia (dubious names) and junior synonyms

- Stegosaurus affinis, described by Marsh in 1881, is only known from a pubis and is considered a nomen nudum.[20] It is possibly synonymous with S. armatus.[24]

- Stegosaurus (Diracodon) laticeps was described by Marsh in 1881, from some jawbone fragments.[25] Bakker resurrected D. laticeps in 1986,[26] although others note that the material is non-diagnostic and referable to Stegosaurus sp.[16]

- Stegosaurus duplex, meaning "two plexus roof lizard" (in allusion to the greatly enlarged neural canal of the sacrum which Marsh characterized as a "posterior brain case"), is probably the same as S. armatus.[20] Although named by Marsh in 1887 (including the holotype specimen), the disarticulated bones were actually collected in 1879 by Edward Ashley at Como Bluff, Wyoming.

Reassigned species

- Stegosaurus longispinus was named by Charles W. Gilmore.[24] It is now the type species of the genus Natronasaurus.[27]

- Stegosaurus madagascariensis from Madagascar is known solely from teeth and was described by Piveteau in 1926. The teeth were variously attributed to a stegosaur, the theropod Majungasaurus,[28] a hadrosaur or even a crocodylian.

- Stegosaurus marshi, which was described by Lucas in 1901, was renamed Hoplitosaurus in 1902.

- Stegosaurus priscus, described by Nopcsa in 1911, was reassigned to Lexovisaurus,[20] and is now the type species of Loricatosaurus.[23]

Paleobiology

Stegosaurus was the largest stegosaur, possibly weighing up to 5,000 kilograms (5.5 short tons). Soon after its discovery, Marsh considered Stegosaurus to have been bipedal, due to its short forelimbs.[29] He had changed his mind however, by 1891, after considering the heavy build of the animal.[30] Although Stegosaurus is undoubtedly now considered to have been quadrupedal, there has been some discussion over whether it could have reared up on its hind legs, using its tail to form a tripod with its hind limbs and browsing for higher foliage.[20] This has been proposed by Bakker[26][31] and opposed by Carpenter.[7]

Stegosaurus did have very short forelimbs, in relation to its hind legs. Furthermore, within the hindlimbs, the lower section (comprising the tibia and fibula) was short compared with the femur. This suggests that it couldn't walk very fast, as the stride of the back legs at speed would have overtaken the front legs, giving a maximum speed of 6–7 kilometers per hour (4–5 mi/hr).[8]

Tracks discovered by Matthew Mossbrucker (Morrison Natural History Museum, Colorado) suggest that Stegosaurus lived in multi-age herds. One group of tracks is interpreted as showing four or five baby stegosaurs moving in the same direction, while another has a juvenile stegosaur track with an adult track overprinting it.[32] Stegosaurus may have preferred drier settings than other common Morrison Formation dinosaurs, such as Allosaurus, Apatosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Diplodocus.[33]

Juveniles

Juveniles of Stegosaurus have been preserved, probably showing the growth of the genus. Kentrosaurus is also known from juvenile specimens, and they can be identified as different genders. The two juveniles are both relatively small, with the smaller individual being 1.5 m (4.9 ft) long, and the larger having a length of 2.6 m (8.5 ft). The specimens can be identified as not mature because they lack the fusion of the scapula and coracoid, and the lower hind limbs. Also, the pelvic region of the specimens are similar to Kentrosaurus juveniles.[34]

Plates

The most recognizable features of Stegosaurus are its dermal plates, which consisted of 17 separate flat plates. These were highly modified osteoderms (bony-cored scales), similar to those seen in crocodiles and many lizards today. They were not directly attached to the animal's skeleton, instead arising from the skin. The largest plates were found over the animal's hips and measured 60 centimeters (2 ft) wide and 60 centimeters tall.

One of the major subjects of books and articles about Stegosaurus is the plate arrangement.[35] The argument has been a major one in the history of dinosaur reconstruction. Four possible plate arrangements have been mooted over the years:

- The plates lie flat along the back, as a shingle-like armor. This was Marsh's initial interpretation, which led to the name 'Roof Lizard'. As further and complete plates were found, their form showed that they stood on edge, rather than lying flat.

- By 1891, Marsh published a more familiar view of Stegosaurus,[30] with a single row of plates. This was dropped fairly early on (apparently because it was poorly understood how the plates were embedded in the skin and it was thought that they would overlap too much in this arrangement). It was revived, in somewhat modified form, in the 1980s, by an artist (Stephen Czerkas),[36] based on the arrangement of iguana dorsal spines.

- The plates were paired in a double row along the back. This is probably the most common arrangement in pictures, especially earlier ones (until the 'Dinosaur Renaissance' in the '70s). (The Stegosaurus in the 1933 film, King Kong, has this arrangement.) However, no two plates of identical size and shape have ever been found for the same animal.

- Two rows of alternating plates. By the early 1960s, this had become (and remains) the prevalent idea, mainly because the one Stegosaurus stenops fossil with the plates still articulated indicates this arrangement. An objection to it is that this phenomenon is unknown among other reptiles and it is difficult to understand how such a disparity could evolve.

In the past, some palaeontologists, notably Robert Bakker, have speculated that the plates may have been mobile to some degree, although others disagree.[37] Bakker suggested that the plates were the bony cores of pointed horn-covered plates that a Stegosaurus could flip from one side to another in order to present a predator with an array of spikes and blades that would impede it from closing sufficiently to attack the Stegosaurus effectively. The plates would naturally sag to the sides of the Stegosaurus, the length of the plates reflecting the width of the animal at that point along its spine. His reasoning for these plates to be covered in horn is that the surface fossilized plates have a resemblance to the bony cores of horns in other animals known or thought to bear horns, and his reasoning for the plates to be defensive in nature is that the plates had insufficient width for them to stand erect easily in such a manner as to be useful in display without continuous muscular effort.[38] Stegosaurus stenops also had disk-shaped plates, on its hips.

The function of the plates has been much debated. Initially thought of as some form of armor,[29] they appear to have been too fragile and ill-placed for defensive purposes, leaving the animal's sides unprotected.[39] The plates' large size suggests that they may have served to increase the apparent height of the animal, in order either to intimidate enemies[24] or to impress other members of the same species, in some form of sexual display,[39] although both male and female specimens seemed to have had the same plates. More recently, researchers have proposed that they may have helped to control the body temperature of the animal,[37] in a similar way to the sails of the pelycosaurs Dimetrodon and Edaphosaurus (and modern elephant and rabbit ears). The plates had blood vessels running through grooves and air flowing around the plates would have cooled the blood.[40] 2010 structural comparisons of Stegosaurus plates to Alligator osteoderms seems to support the conclusion that the potential for a thermoregulatory role in the plates of Stegosaurus definitely exists.[41] This hypothesis has been seriously questioned,[42] since its closest relatives, such as Kentrosaurus, had more low surface area spikes than plates, implying that cooling was not important enough to require specialized structural formations such as plates. Another possible function is that the plates may have helped the animal increase heat absorption from the sun. Since there was a cooling trend towards the end of the Jurassic, a large ectothermic reptile might have used the increased surface area afforded by the plates to absorb radiation from the sun.

The publication of "Growth and Function of Stegosaurus Plates"[37] by Buffrénil, et al. in 1986 marked a major step out of the realm of speculation and into the realm of science, with its microscopic analyses of multiple Stegosaurus plate specimens, proving unequivocally "extreme vascularization of the outer layer of bone,"[43] which was seen by Buffrénil as further evidence the plates "acted as thermoregulatory devices."[43] Later, more comprehensive histological surveys of plate microstructure attributed the vascularization to the need to transport nutrients for rapid plate growth, asserting the plates' physiology, if beneficial, was a side-benefit secondary to their primary function, identification and display.[43][44]

The latest explanation for Stegosaurus plates' heavily vascular design is that, when under threat, blood could rush into the plates, causing them to "blush" which would add a colorful, red warning, "embellishing"[45] the visual threat display.[46] This "blushing capacity," instead of thermoregulatory functions, may be the plates' purpose,[7] though the two functions certainly could have co-existed. That Stegosaurus plates could "blush" has become the predominant interpretation of plate function since the late 20th century, and is even depicted in the popular BBC documentary Walking with Dinosaurs, with the sudden reddening of the plates used in conjunction with threatening swings of the spiked tail to intimidate and confuse an attacking Allosaurus. It is also possible that this blushing could have been used to attract mates.[46] A study published in 2005 supports the idea of their use in species identification. Researchers believe this may be the function of other unique anatomical features, found in various dinosaur species.[44]

Thagomizer (tail spikes)

There has been debate about whether the tail spikes were used for display only, as posited by Gilmore in 1914[24] or used as a weapon. Robert Bakker noted the tail was likely to have been much more flexible than that of other dinosaurs, as it lacked ossified tendons, thus lending credence to the idea of the tail as a weapon. However, as Carpenter[7] has noted, the plates overlap so many tail vertebrae that movement would be limited. Bakker also observed that Stegosaurus could have maneuvered its rear easily, by keeping its large hindlimbs stationary and pushing off with its very powerfully muscled but short forelimbs, allowing it to swivel deftly to deal with attack.[26] More recently, a study of tail spikes by McWhinney et al.,[47] which showed a high incidence of trauma-related damage, lends more weight to the position that the spikes were indeed used in combat. This study showed that 9.8% of Stegosaurus specimens examined had injuries to their tail spikes. Additional support for this idea was a punctured tail vertebra of an Allosaurus into which a tail spike fit perfectly.[48]

Stegosaurus stenops had four dermal spikes, each about 60–90 centimeters (2–3 ft) long. Discoveries of articulated stegosaur armor show that, at least in some species, these spikes protruded horizontally from the tail, not vertically as is often depicted.[7] Initially, Marsh described S. armatus as having eight spikes in its tail, unlike S. stenops. However, recent research re-examined this and concluded this species also had four.[16]

"Second brain"

Soon after describing Stegosaurus, Marsh noted a large canal in the hip region of the spinal cord, which could have accommodated a structure up to 20 times larger than the famously small brain. This has led to the influential idea that dinosaurs like Stegosaurus had a "second brain" in the tail, which may have been responsible for controlling reflexes in the rear portion of the body. It has also been suggested that this "brain" might have given a Stegosaurus a temporary boost when it was under threat from predators.[8] More recently, it has been argued that this space (also found in sauropods) may have been the location of a glycogen body, a structure in living birds whose function is not definitely known but which is postulated to facilitate the supply of glycogen to the animal's nervous system.[49]

Diet

Stegosaurus and related genera were herbivores. However, their teeth and jaws are very different from those of other herbivorous ornithischian dinosaurs, suggesting a different feeding strategy that is not yet well understood. The other ornithischians possessed teeth capable of grinding plant material and a jaw structure capable of movements in planes other than simply orthal (i.e. not only the fused up-down motion stegosaur jaws were likely limited to). Unlike the sturdy jaws and grinding teeth common to its fellow ornithischians, Stegosaurus (and all stegosaurians) had small, peg-shaped teeth that have been observed with horizontal wear facets associated with tooth-food contact[50] and their unusual jaws were probably capable of only orthal (up-down) movements.[20] Their teeth were "not tightly pressed together in a block for efficient grinding,"[51] and there is no evidence in the fossil record of stegosaurians using gastroliths—the stone(s) some dinosaurs (and some present-day bird species) ingested—to aid the grinding process, so how exactly Stegosaurus obtained and processed the amount of plant material required to sustain its size remains "poorly understood."[51]

The stegosaurians were geographically widely distributed in the late Jurassic.[20] Palaeontologists believe it would have eaten plants such as mosses, ferns, horsetails, cycads and conifers or fruits.[52] Grazing on grasses, seen in many modern mammalian herbivores, would not have been possible for Stegosaurus, as grasses did not evolve until late into the Cretaceous Period, long after Stegosaurus had become extinct.

One hypothesized feeding behavior strategy considers them to be low-level browsers, eating low-growing fruit of various non-flowering plants, as well as foliage. This scenario has Stegosaurus foraging at most one meter above the ground.[53] On the other hand, if Stegosaurus could have raised itself on two legs, as suggested by Bakker, then it could have browsed on vegetation and fruits quite high up, with adults being able to forage up to 6 meters (20 ft) above the ground.[8]

A detailed computer analysis of the biomechanics of Stegosaurus's feeding behavior was performed in 2010, using two different three-dimensional models of Stegosaurus teeth given realistic physics and properties. Bite force was also calculated using these models and the known skull proportions of the animal as well as simulated tree branches of different size and hardness. The resultant bite forces calculated for Stegosaurus were 140.1 N (Newton), 183.7 N, and 275 N (for anterior, middle and posterior teeth, respectively), which means that its bite force was less than half that of a Labrador retriever. This indicates that Stegosaurus could have easily bitten through smaller green branches, but would have had difficulty with anything over 12 mm in diameter. Stegosaurus, therefore, probably browsed primarily among smaller twigs and foliage, and would have been unable to handle larger plant parts unless the animal was capable of biting much more efficiently than predicted in this study.[54]

Paleoecology

The Morrison Formation is interpreted as a semiarid environment with distinct wet and dry seasons, and flat floodplains. Vegetation varied from river-lining forests of conifers, tree ferns, and ferns (gallery forests), to fern savannas with occasional trees such as the Araucaria-like conifer Brachyphyllum.The flora of the period has been revealed by fossils of green algae, fungi, mosses, horsetails, ferns, cycads, ginkgoes, and several families of conifers. Animal fossils discovered include bivalves, snails, ray-finned fishes, frogs, salamanders, turtles, sphenodonts, lizards, terrestrial and aquatic crocodylomorphans, several species of pterosaur, numerous dinosaur species, and early mammals such as docodonts, multituberculates, symmetrodonts, and triconodonts.[55]

Dinosaurs that lived alongside Stegosaurus included theropods Allosaurus, Saurophaganax, Torvosaurus, Ceratosaurus, Marshosaurus, Stokesosaurus and Ornitholestes. Sauropods dominated the region, and included Brachiosaurus, Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, Camarasaurus, and Barosaurus. Other ornithischians included Camptosaurus, Gargoyleosaurus,Dryosaurus, and Othnielosaurus.[56] Stegosaurus is commonly found at the same sites as Allosaurus, Apatosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Diplodocus.[33]

Popular culture

One of the most recognizable of all dinosaurs,[8] Stegosaurus has been depicted on film, in cartoons, comics, as children's toys, and was even declared the State Dinosaur of Colorado in 1982.[57]

Footnotes

- ^ "stegosaurus". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b Escaso F, Ortega F, Dantas P, Malafaia E, Pimentel NL, Pereda-Suberbiola X, Sanz JL, Kullberg JC, Kullberg MC, Barriga F. (2007). "New Evidence of Shared Dinosaur Across Upper Jurassic Proto-North Atlantic: Stegosaurus From Portugal". Naturwissenschaften. 94 (5): 367–74. doi:10.1007/s00114-006-0209-8. PMID 17187254.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Turner, C.E. and Peterson, F., (1999). "Biostratigraphy of dinosaurs in the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of the Western Interior, U.S.A." Pp. 77–114 in Gillette, D.D. (ed.), Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah. Utah Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication 99-1.

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix.

- ^ Martin, A.J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. 560 pp. ISBN 1–4051–3413–5.

- ^ Lambert D (1993). The Ultimate Dinosaur Book. Dorling Kindersley, New York. pp. 110–29. ISBN 1-56458-304-X.

- ^ a b c d e Carpenter K (1998). "Armor of Stegosaurus stenops, and the taphonomic history of a new specimen from Garden Park Colorado". The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Part 1. Modern Geol. Vol. 22. pp. 127–44.

- ^ a b c d e Fastovsky DE, Weishampel DB (2005). "Stegosauria: Hot Plates". In Fastovsky DE, Weishampel DB (ed.). The Evolution and Extinction of the Dinosaurs (2nd Edition). Cambridge University Press. pp. 107–30. ISBN 0-521-81172-4.

- ^ Bakker RT (1986). The Dinosaur Heresies. William Morrow, New York. pp. 365–74.

- ^ Buchholtz, Emily; Holtz, Thomas R., Jr.; Farlow, James O.; Walters, Bob. Brett-Surman, M.K. (ed.). The complete dinosaur (2nd ed.). Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-253-00849-7. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

Proportions and anatomy of endocasts of Stegosaurus vary little from those of ancestral archosaurs, with an elongated shape, large olfractory lobes, and extremely narrow cerebral hemispheres. Lack of surface detail suggest that the brain did not fill the braincase. EQ estimates are below 0,6 (Hoppson, 1977), agreeing well with predictions of a slow herbivorous lifestyle.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stegosaurus. University of Wyoming Geological Museum. 2006. Retrieved October 6, 2006. University of Wyoming Geological Museum Template:Wayback

- ^ O. Mateus, S. C. R. Maidment, and N. A. Christiansen (2009). "A new long-necked 'sauropod-mimic' stegosaur and the evolution of the plated dinosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276: 1815–1821. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1909. PMC 2674496. PMID 19324778.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carpenter K, Miles CA, Cloward K (2001). "New Primitive Stegosaur from the Morrison Formation, Wyoming". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 55–75. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Le Loeuff J, Lockley M, Meyer C, Petit J-P (1999). "Discovery of a thyreophoran trackway in the Hettangian of central France". C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris. 2 (328): 215–219. doi:10.1016/S1251-8050(99)80099-8.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Marsh OC (1877). "A new order of extinct Reptilia (Stegosauria) from the Jurassic of the Rocky Mountains". American Journal of Science. 3 (14): 513–514.

- ^ a b c Carpenter K, Galton PM (2001). "Othniel Charles Marsh and the Eight-Spiked Stegosaurus". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 76–102. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.

- ^ Foster, J. (2007). Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327–329. ISBN 0253348706.

- ^ a b Galton, Peter M.; Upchurch, Paul (2004). "Stegosauria (Table 16.1)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 344–45. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ^ Marsh OC (1879). "Notice of new Jurassic reptiles" (PDF). American Journal of Science. 3 (18): 501–505.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Galton PM, Upchurch P (2004). "Stegosauria". In Weishampel DB, Dodson P, Osmólska H (ed.). The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). University of California Press. p. 361. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b Marsh OC (1887). "Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs, part IX. The skull and dermal armour of Stegosaurus". American Journal of Science. 3 (34): 413–17.

- ^ a b Galton, P.M. (2010). "Species of plated dinosaur Stegosaurus (Morrison Formation, Late Jurassic) of western USA: new type species designation needed". Swiss Journal of Geosciences. 103 (2): 187–198. doi:10.1007/s00015-010-0022-4.

- ^ a b Maidment, Susannah C.R.; Norman, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Upchurch, Paul (2008). "Systematics and phylogeny of Stegosauria (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (4): 1. doi:10.1017/S1477201908002459. Cite error: The named reference "SMetal08" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d Gilmore CW (1914). "Osteology of the armored Dinosauria in the United States National Museum, with special reference to the genus Stegosaurus". Series: Smithsonian Institution. United States National Museum. Bulletin 89 (89). Government Printing Office, Washington.

- ^ Marsh OC (1881). "Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs, part V". American Journal of Science. 3 (21): 417–23.

- ^ a b c Bakker RT (1986). The Dinosaur Heresies. William Morrow, New York. ISBN 0-8217-2859-8.

- ^ Ulansky, R. E., 2014. Evolution of the stegosaurs (Dinosauria; Ornithischia). Dinologia, 35 pp. [in Russian]. [DOWNLOAD PDF] http://dinoweb.narod.ru/Ulansky_2014_Stegosaurs_evolution.pdf.

- ^ Galton PM (1981) "Craterosaurus pottonensis Seeley, a stegosaurian dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of England, and a review of Cretaceous stegosaurs". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 161(1):28–46

- ^ a b Marsh, Othniel Charles (1880). "Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs, part III". American Journal of Science. 3 (19): 253–59.

- ^ a b Marsh, Othniel Charles (1891). "Restoration of Stegosaurus". American Journal of Science. 3 (42): 179–81.

- ^ Bakker RT (1978). "Dinosaur feeding behavior and the origin of flowering plants". Nature. 274 (274): 661–63. doi:10.1038/274661a0.

- ^ Rajewski, Genevieve (May 2008). "Where Dinosaurs Roamed". Smithsonian: 20–24. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ a b Dodson, Peter; Behrensmeyer, A.K.; Bakker, Robert T.; McIntosh, John S. (1980). "Taphonomy and paleoecology of the dinosaur beds of the Jurassic Morrison Formation". Paleobiology. 6 (2): 208–232.

- ^ Galton, P.M. (1982). "Juveniles of the stegosaurian dinosaur Stegosaurus from the Upper Jurassic of North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 2 (1): 47–62. doi:10.1080/02724634.1982.10011917.

- ^ Colbert EH (1962). Dinosaurs: Their Discovery & Their World. Hutchinson Press, London. pp. 82–99. ISBN 1-111-21503-0.

- ^ Czerkas SA (1987). "A Reevaluation of the Plate Arrangement on Stegosaurus stenops". In Czerkas SJ, Olson EC (ed.). Dinosaurs Past & Present, Vol 2. University of Washington Press, Seattle. pp. 82–99. ISBN.

- ^ a b c Buffrénil (1986). "Growth and Function of Stegosaurus Plates". Paleobiology. 12: 459–73.

- ^ Bakker, R (1986). The Dinosaur Heresies. Penguin Books. pp. 229–34. ISBN 0-14-015792-1.

- ^ a b Davitashvili L (1961). The Theory of sexual selection. Izdatel'stvo Akademia nauk SSSR. p. 538.

- ^ Farlow JO, Thompson CV, Rosner DE (1976). "Plates of the dinosaur Stegosaurus:Forced convection heat loss fins?". Science. 192 (4244): 1123–25. doi:10.1126/science.192.4244.1123. PMID 17748675.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Farlow, James O.; Hayashi, Shoji; Tattersall, Glenn J. (2010). "Internal vascularity of the dermal plates of Stegosaurus (Ornithischia, Thyreophora)" (PDF). Swiss J Geoscia. 103 (2): 173–85. doi:10.1007/s00015-010-0021-5.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Main RP, Padian K, Horner J (2000). "Comparative histology, growth and evolution of archosaurian osteoderms: why did Stegosaurus have such large dorsal plates?". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 56A (20).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Stephen Brusatte (February 2012). Dinosaur Paleobiology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b "Stegosaur plates used for identification". National Geographic website. National Geographic News. 25 May 2005. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- ^ Carpenter, K. (June 1998). Fraser, Nick (ed.). Armor of Stegosaurus stenops and the taphonomic history of a new specimen from Garden Park, Colorado. Morrison Symposium. Morrison Symposium Proceedings. Taylor & Francis. p. 137. ISBN 978-9056991838.

- ^ a b Kenneth Carpenter, Dan Chure, James Ian Kirkland, Denver Museum of Natural History (1998). The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: an interdisciplinary study Part 2. Taylor & Francis. p. 137. ISBN 90-5699-183-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McWhinney LA, Rothschild BM, Carpenter K (2001). "Posttraumatic Chronic Osteomyelitis in Stegosaurus dermal spikes". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed) (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 141–56. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carpenter K, Sanders F, McWhinney L, Wood L (2005). "Evidence for predator-prey relationships: Examples for Allosaurus and Stegosaurus.". In Carpenter, Kenneth(ed) (ed.). The Carnivorous Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 325–50. ISBN 0-253-34539-1.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Buchholz (née Giffin) EB (1990). "Gross Spinal Anatomy and Limb Use in Living and Fossil Reptiles". Paleobiology. 16: 448–58.

- ^ Barrett PM (2001). "Tooth wear and possible jaw action of Scelidosaurus harrisoni, and a review of feeding mechanisms in other thyreophoran dinosaurs". In Carpenter, Kenneth(ed) (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 25–52. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Fastovsky, David E. and Weishampel, David B. (2009). Dinosaurs: A Concise Natural History. Cambridge, GBR: Cambridge University Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 9780511477898.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stegosaurus ungulatus Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 26 October 2006. Template:Wayback

- ^ Weishampel DB (1984). "Interactions between Mesozoic Plants and Vertebrates:Fructifications and seed predation". N. Jb. Geol. Paläontol. Abhandl. 167: 224–50.

- ^ Reichel, Miriam (2010). "A model for the bite mechanics in the herbivorous dinosaur Stegosaurus (Ornithischia, Stegosauridae)". Swiss Journal of Geosciences. 103 (2): 235. doi:10.1007/s00015-010-0025-1.

- ^ Chure, Daniel J.; Litwin, Ron; Hasiotis, Stephen T.; Evanoff, Emmett; and Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "The fauna and flora of the Morrison Formation: 2006". In Foster, John R.; and Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 233–248.

- ^ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327-329.

- ^ "Colorado Department of Personnel website – State emblems". Colorado.gov. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

External links