Crucifixion darkness

The Crucifixion darkness is an episode in three of the Canonical Gospels in which the sky becomes dark in daytime during the crucifixion of Jesus.

Ancient and medieval Christian writers, and Christians today, treat this as a miracle, and believed it to be one of the episodes from the New Testament which were confirmed by non-Christian sources. Pagan commentators of the Roman era explained it as an eclipse, although Christian writers pointed out that an eclipse during Passover, when the crucifixion took place, would have been impossible; an eclipse cannot occur during a full moon.

Some modern scholarship, noting the way in which similar accounts were associated in ancient times with the deaths of notable figures, tends to look upon this phenomenon as a literary invention that attempts to convey a sense of the power of Jesus in the face of death, or a sign of God's displeasure with the Jewish people.

Biblical account

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

| Part of a series on |

| Death and Resurrection of Jesus |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

The oldest biblical reference to the crucifixion darkness is found in the Book of Amos. The event is seen as a fulfilment of an Old Testament prediction by the prophet Amos, written over 800 years before the crucifixion;

"In that day," declares the Sovereign LORD, "I will make the sun go down at noon and darken the earth in broad daylight [1]

In the new testament it is first mentioned in the Gospel of Mark, written around the year 70.[2][3] In its account of the crucifixion, on the eve of Passover, it says that after Jesus was crucified at nine in the morning, darkness fell over all the land, or all the world (Greek: γῆν, translit. gēn can mean either) from around noon ("the sixth hour") until 3 o'clock ("the ninth hour").[4] It adds, immediately after the death of Jesus, that "the curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom".[5]

The Gospel of Matthew, written around the year 85 or 90, and using Mark as a source,[6] has an almost identical wording: "From noon on, darkness came over the whole land [or, earth] until three in the afternoon."[7] The author adds some dramatic details, including an earthquake and the raising of the dead, which were stock motifs from Jewish apocalyptic literature:[8][9] "The earth shook, and the rocks were split. The tombs also were opened, and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised." [10]

The Gospel of Luke, written around the year 90 and also using Mark as a source,[11] has none of the details added in the Matthew version, moves the tearing of the temple veil to before the death of Jesus,[12] and explains the darkness as a darkening of the sun:[13][14]

It was now about noon, and darkness came over the whole land [or, earth] until three in the afternoon, while the sun's light failed [or, the sun was eclipsed]; and the curtain of the temple was torn in two.[15]

The majority of manuscripts of the Gospel of Luke have the Greek phrase "eskotisthe ho helios" ("the sun was darkened"), but the earliest manuscripts say "tou heliou eklipontos" ("the sun's light failed" or "the sun was in eclipse"), appearing to explain the event as an eclipse.[16] This earlier version is likely to have been the original one, amended by later scribes to correct what they assumed was an error, since they knew that an eclipse was impossible during Passover.[17][18] One early Christian commentator even suggested that the text had been deliberately corrupted by opponents of the Church to make it easier to attack.[19]

The account of the crucifixion given in the Gospel of John is very different. It takes place on the day of Passover,[20] the crucifixion does not take place until after noon, and there is no mention of darkness, the tearing of the veil, or the raising of the dead.[21]

Later versions

Apocryphal writers

A number of accounts in apocryphal literature build on the synoptic accounts of the crucifixion darkness. The Gospel of Peter, probably from the second century, expands on the canonical gospel accounts of the passion narrative in creative ways. As one writer puts it, "accompanying miracles become more fabulous and the apocalyptic portents are more vivid".[22] In this version, the darkness which covers the whole of Judaea leads people to go about with lamps believing it to be night.[23] The fourth century Gospel of Nicodemus describes how Pilate and his wife are disturbed by a report of what had happened, and the Judeans he has summoned tell him it was an ordinary solar eclipse.[24] Another text from the fourth century, the purported Report of Pontius Pilate to Tiberius, claimed the darkness had started at the sixth hour, covered the whole world, and during the subsequent evening the full moon resembled blood for the entire night.[25] In a fifth- or sixth-century text by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, the author claims to have observed a solar eclipse from Heliopolis at the time of the crucifixion.[26]

Ancient historians

There are references to this darkness outside the New Testament. The first was by Phlegon of Tralles. Phlegon of Tralles (Ancient Greek: Φλέγων) was a secular Greek writer , historian and freedman of the emperor Hadrian, who lived in the 2nd century AD, born not long after the Crucifixion. Phlegon's greatest work was the writing of a history book, called The Olympiades. The Olympiades can be used as a useful means of establishing a time-line, and it seems he inadvertently dated the darkness at noon on the day of Crucifixion in his work, The Olympiades. In ancient Greece the Olympic Games were held in the July of the first year of each Olympiad, which was a 4 year period running from July to June of each succeeding year. We only have fragments left to us of this monumental work and quotations of it from other writers.

One such quotation is as follows, "In the 4th year of the 202nd Olympiad, there was a great eclipse of the Sun, greater than had ever been known before, for at the sixth hour the day was changed into night, and the stars were seen in the heavens. An earthquake occurred in Bythinia and overthrew a great part of the city of Nicæa."[27]

The second record of this darkness event, was by Thallus (Greek: Θαλλός). Thallus was an early Roman historian who wrote in Koine Greek. He wrote a three-volume history of the Mediterranean world from before the Trojan War to the 167th Olympiad, c. 112-109 BC. Most of his work, like the vast majority of ancient literature, perished, but not before parts of his writings were repeated by an able historian Sextus Julius Africanus in his own ‘A History of the World’, which was written around 220. Africanus, whilst noting what Thallus had said, differed in his view that it was and eclipse that caused the darkness event, but rather a ‘darkness induced by God’ and therefore miraculous. Here is the passage from Africanus:

‘On the whole world there pressed a most fearful darkness; and the rocks were rent by an earthquake, and many places in Judea and other districts were thrown down'[28]

The crucifixion darkness story has been often used by Christian apologists because they believed it was a rare example of the Biblical account being supported by non-Christian sources. When the pagan critic Celsus claimed that Jesus could hardly be a God because he had performed no great deeds, the third-century Christian commentator Origen responded, in Against Celsus, by recounting the darkness, earthquake and opening of tombs. As proof that the incident had happened, he referred to the description by Phlegon of Tralles of the eclipse accompanied by earthquakes during the reign of Tiberius.[29]

Explanations

Miracle

Because it was known in ancient and medieval times that a solar eclipse could not take place during Passover (solar eclipses require a new moon while Passover only takes place during a full moon) it was considered a miraculous sign rather than a naturally occurring event.[30] The astronomer Johannes de Sacrobosco wrote, in his The Sphere of the World, "the eclipse was not natural, but, rather, miraculous and contrary to nature".[31] Modern writers who regard this as a miraculous event tend either to see it as operating through a natural phenomenon—such as volcanic dust or heavy cloud cover—or avoid explanation completely.[32] The Reformation Study Bible, for instance, simply states "This was a supernatural darkness."[33]

Naturalistic explanations

The Gospel of Luke account appears to describe the event as an eclipse, and some non-Christian writers dismissed it in these terms. However, the biblical details do not accord with an eclipse: a solar eclipse could not have occurred on or near the Passover, when Jesus was crucified, and would have been too brief to account for three hours of darkness. The maximum possible duration of a total solar eclipse is seven minutes and 31.1 seconds.[34] A total eclipse on 24 November 29 CE was visible slightly north of Jerusalem at 11:05 AM.[35] The period of totality in Nazareth and Galilee was one minute and forty-nine seconds, and the level of darkness would have been unnoticeable for people outdoors.[36]

In 1983, Colin Humphreys and W. G. Waddington, who had used astronomical methods to calculate the crucifixion date as 3 April 33,[37] argued that the darkness could be accounted for by a partial lunar eclipse that had taken place on that day.[38] Astronomer Bradley E. Schaefer, on the other hand, pointed out that the eclipse would not have been visible during daylight hours.[39][40] Humphreys and Waddington speculated that the reference in the Luke Gospel to a solar eclipse must have been the result of a scribe wrongly amending the text, a claim historian David Henige describes as "indefensible".[13]

Some writers have explained the crucifixion darkness in terms of sunstorms, heavy cloud cover, or the aftermath of a volcanic eruption.[41] Another possible natural explanation is a khamsin dust storm that tends to occur from March to May.[42]

One explanation is that this darkness was caused by "Earthquake smog", a precursor of an upcoming earthquake. A similar occurrence occurred during the New Madrid Earthquake of 1811–12. The skies turned dark during the earthquakes, so dark that lighted lamps didn’t help.[43] The air smelled bad, and it was hard to breathe. It is speculated that it was smog containing dust particles caused by the eruption of warm water into cold air. This type of event has been witnessed for thousands of years and was once thought to be the cause of Earthquakes. Aristotle describes some of the fog’s properties:

"Again, our theory is supported by the facts that the sun appears hazy and is darkened in the absence of clouds, and that there is sometimes calm and sharp frost before earthquakes at sunrise."

Today, we know that some of these ancient explanations are really earthquake precursors identified by modern science.[44] The Earth-Degassing Theory states that during the preparatory phase of an earthquake, in high tectonic stress, pore spaces in the rocks are reduced due to subsurface pressure releasing the trapped gases. These gases on reaching earth’s surface are already at an elevated temperature with respect to the air temperature due to subsurface geothermal heat and secondly, it also creates a local greenhouse effect on the land surface thus serving as the source of outgoing anomalous radiation. Positive thermal anomalies at a regional scale were observed with the examination of around 9000 thermal images for the Middle Asian earthquake. These anomalies were attributed to the green house effect that was caused before the earthquake by an increase in gases like CO2, CH4, etc. A new theory of charge generation in rocks prior to earthquakes is given by Freund (2000, 2002 and 2003). This theory keeps parity with laboratory experiments and also provides explanation for other observed geophysical precursors. Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

Literary creation

A common view in modern scholarship is that the account in the synoptic gospels is a literary creation of the gospel writers, intended to heighten the importance of what they saw as a theologically significant event. Burton Mack describes it as a fabrication by the author of the Gospel of Mark,[45] while G. B. Caird and Joseph Fitzmyer conclude that the author did not intend the description to be taken literally.[46][47] W. D. Davies and Dale Allison similarly conclude "It is probable that, without any factual basis, darkness was added in order to wrap the cross in a rich symbol and/or assimilate Jesus to other worthies".[48]

The image of darkness over the land would have been understood by ancient readers as a cosmic sign, a typical element in the description of the death of kings and other major figures by writers such as Philo, Dio Cassius, Virgil, Plutarch and Josephus.[49] Géza Vermes describes the darkness account as "part of the Jewish eschatological imagery of the day of the Lord. It is to be treated as a literary rather than historical phenomenon notwithstanding naive scientists and over-eager television documentary makers, tempted to interpret the account as a datable eclipse of the sun. They would be barking up the wrong tree".[50]

Interpretations

This sequence plays an important part in the gospel's literary narrative. The author of Mark's gospel has been described as operating here "at the peak of his rhetorical and theological powers".[51] One suggestion is that the darkness is a deliberate inversion of the transfiguration;[51] alternately, Jesus's earlier discourse about a future tribulation mentions the sun being darkened,[52] and can be seen as foreshadowing this scene.[53] Striking details such as the darkening of the sky and the tearing of the temple veil may be a way of focusing the reader away from the shame and humiliation of the crucifixion; one professor of biblical theology concluded, "it is clear that Jesus is not a humiliated criminal but a man of great significance. His death is therefore not a sign of his weakness but of his power."[54]

When considering the theological meaning of the event, some authors have interpreted the darkness as a period of mourning by the cosmos itself at the death of Jesus.[55] Others have seen it as a sign of God's judgement on the Jewish people, sometimes connecting it with the destruction of the city of Jerusalem in the year 70; or as symbolising shame, fear, or the mental suffering of Jesus.[56] Fitzmyer compares the event to a contemporary description recorded in Josephus' Antiquities of the Jews,[57] which recounts "unlawful acts against the gods, from which we believe the very sun turned away, as if it too were loath to look upon the foul deed".[58]

Many writers have adopted an intertextual approach, looking at earlier texts from which the author of the Mark Gospel may have drawn. In particular, parallels have often been noted between the darkness and the prediction in the Book of Amos of an earthquake in the reign of King Uzziah of Judah: "On that day, says the Lord God, I will make the sun go down at noon, and darken the earth in broad daylight".[59] Particularly in connection with this reference, read as a prophecy of the future, the darkness can be seen as portending the end times.[60]

Another likely literary source is the plague narrative in the Book of Exodus, in which Egypt is covered by darkness for three days.[61] It has been suggested that the author of the Matthew Gospel changed the Marcan text slightly to more closely match this source.[62] Commentators have also drawn comparisons with the description of darkness in the Genesis creation narrative,[63] with a prophecy regarding mid-day darkness by Jeremiah,[64] and with an end-times prophecy in the Book of Zechariah.[65][66]

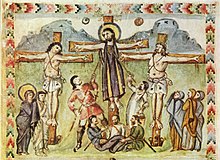

Iconography

In traditional artistic representations of the crucifixion, the sun and moon sometimes appear above and to either side of the cross, in allusion to the darkening of the skies.

Notes

- ^ Amos 8:9

- ^ Witherington (2001), p. 31: 'from 66 to 70, and probably closer to the latter'

- ^ Hooker (1991), p. 8: 'the Gospel is usually dated between AD 65 and 75.'

- ^ Mark 15:33

- ^ Mark 15:38

- ^ Harrington (1991), p. 8.

- ^ Matthew 27:45

- ^ Yieh (2004), p. 65.

- ^ Funk (1998), pp. 129–270, "Matthew".

- ^ Matthew 27:51–54

- ^ Davies (2004), p. xii.

- ^ Evans (2011), p. 308.

- ^ a b Henige (2005), p. 150.

- ^ Funk (1998), pp. 267–364, "Luke".

- ^ Luke 23:44–45

- ^ Loader (2002), p. 356.

- ^ Fitzmyer (1985), pp. 1517–1518.

- ^ Wallace (2004).

- ^ Allison (2005), p. 89.

- ^ Barclay (2001), p. 340.

- ^ Broadhead (1994), p. 196.

- ^ Foster (2009), p. 97.

- ^ Roberts, Donaldson & Coxe (1896), Volume IX, "The Gospel of Peter" 5:15, p. 4.

- ^ Barnstone (2005), pp. 351, 368, 374, 378–379, 419.

- ^ Roberts, Donaldson & Coxe (1896), Volume VIII, "The Report of Pontius Pilate", pp. 462–463.

- ^ Parker (1897), pp. 148–149, 182–183.

- ^ Phlegon of Tralles' Book of Marvels. Translated with an introduction and commentary by William Hansen. University of Exeter Press (1996), and Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. pp 19–20 Google Link Africanus, in Syncellus

- ^ Roberts, Donaldson & Coxe (1896), Volume IV, "Contra Celsum", Book II, chapter 23 p. 441.

- ^ Chambers (1899), pp. 129–130.

- ^ Bartlett (2008), pp. 68–69.

- ^ Allison (2005), pp. 68–69.

- ^ Sproul (2010), comment on Luke 23:44.

- ^ Meeus (2003).

- ^ Espenak, "Total Solar Eclipse of 0029 Nov 24".

- ^ Kidger (1999), pp. 68–72.

- ^ Humphreys & Waddington (1983).

- ^ Humphreys & Waddington (1985).

- ^ Schaefer (1990).

- ^ Schaefer (1991).

- ^ Brown (1994), p. 1040.

- ^ Humphreys (2011), p. 84.

- ^ Lorenzo Dow's Journal, Published By Joshua Martin, Printed By John B. Wolff, 1849, on pages 344 - 346.p, [1]

- ^ Tributsch Helmut, The escaping “pneuma” – gas of ancient earthquake concepts in relation to animal, atmospheric and thermal precursors, [2].

- ^ Mack (1988), p. 296, 'This is the earliest account there is about the crucifixion of Jesus. It is a Markan fabrication'

- ^ Caird (1980), p. 186.

- ^ Fitzmyer (1985), p. 1513.

- ^ Davies & Allison (1997), p. 623.

- ^ Garland (1999), p. 264.

- ^ Vermes (2005), pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b Black (2005), p. 42.

- ^ Mark 13:24

- ^ Healy (2008), p. 319.

- ^ Winn (2008), p. 133.

- ^ Donahue (2002), pp. 451–452.

- ^ Allison (2005), pp. 97–102.

- ^ Fitzmyer (1985), p. 1518.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities, Book XIV 12:3 (text at Wikisource).

- ^ Amos 8:8–9

- ^ Allison (2005), pp. 100–101.

- ^ Exodus 10:22

- ^ Allison (2005), pp. 182–83.

- ^ Genesis 1:2

- ^ Jeremiah 15:9

- ^ Zechariah 14:6–7

- ^ Allison (2005), pp. 83–84.

References

- Books

- Alexander, Loveday (2005). "The Four among pagans". In Bockmuehl, Markus; Hagner, Donald A. (eds.). The Written Gospel. Cambridge University Press. pp. 222–237. ISBN 9781139445726.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Allison, Dale C. (2005). Studies in Matthew: Interpretation Past and Present. Baker Academic. ISBN 9780801027918.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barclay, William (2001). The Gospel of John, Volume 1. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664237806.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barnstone, Willis, ed. (2005). "The Gospel of Nicodemus". The Other Bible. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780060815981.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bartlett, Robert (2008). The Natural and the Supernatural in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521878326.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Black, C. Clifton (2005). "The Face is Familiar—I Just Can't Place It". In Gaventa, Beverley Roberts; Miller, Patrick D. (eds.). The Ending of Mark and the Ends of God: Essays in Memory of Donald Harrisville Juel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227395.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Broadhead, Edwin Keith (1994). Prophet, Son, Messiah: Narrative Form and Function in Mark. Continuum. ISBN 9781850754763.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brown, Raymond E. (1994). The Death of the Messiah: a Commentary on the Passion Narratives in the Four Gospels. The Anchor Bible Reference Library. Vol. Volume 2: From Gethsemane to the Grave. Doubleday. ISBN 9780385193979.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Caird, George Bradford (1980). The language and imagery of the Bible. Westminster Press. ISBN 9780664213787.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chambers, George F. (1899). The Story of Eclipses. George Newnes, Ltd.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, Stevan L. (2004). The Gospel of Thomas and Christian Wisdom. Bardic Press. ISBN 9780974566740.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, William David; Allison, Dale C. (1997). Matthew: Volume 3. Continuum. ISBN 9780567085184.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Donahue, John R. (2002). The Gospel of Mark. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658048.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Evans, Craig A. (2011). Luke (Understanding the Bible Commentary Series). Baker Books. ISBN 9781441236524.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fitzmyer, Joseph A. (1985). The Gospel According to Luke, X-XXIV. The Anchor Bible Reference Library. Doubleday. ISBN 9780300139815.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Foster, Paul (2009). The Apocryphal Gospels: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191578953.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Funk, Robert Walter (1998). The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 9780060629786.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Garland, David E. (1999). Reading Matthew: A Literary and Theological Commentary on the First Gospel. Smyth & Helwys Publishing. ISBN 9781573122740.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harrington, Daniel J. (1991). The Gospel of Matthew. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658031.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Healy, Mary (2008). The Gospel of Mark. Baker Academic. ISBN 9780801035869.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Henige, David P. (2005). Historical evidence and argument. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-21410-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hooker, Morna (1991). The Gospel According to Saint Mark. Continuum. ISBN 9780826460394.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Humphreys, Colin J. (2011). The Mystery of the Last Supper: Reconstructing the Final Days of Jesus. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139496315.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kidger, Mark (1999). The Star of Bethlehem: An Astronomer's View. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691058238.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Loader, William (2002). Jesus' Attitude Towards the Law: A Study of the Gospels. W.B. Eerdmans Pub. ISBN 9780802849038.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mack, Burton L. (1988). A Myth of Innocence: Mark and Christian Origins. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451404661.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Parker, John (1897). "Letter VII. Section II. To Polycarp--Hierarch. & Letter XI. Dionysius to Apollophanes, Philosopher". The Works of Dionysius the Arepagite. London: James Parker and Co. ISBN 9781440092398.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Roberts, Alexander; Donaldson, James; Coxe, Arthur Cleveland, eds. (1896). The Ante-Nicene Fathers. T&T Clark.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sproul, R. C., ed. (2010). The Reformation Study Bible. Ligonier Ministries. ISBN 978-1596382077.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vermes, Géza (2005). The Passion. Penguin. ISBN 9780141021324.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Winn, Adam (2008). The Purpose of Mark's Gospel: An Early Christian Response to Roman Imperial Propaganda. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161496356.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Witherington, Ben (2001). The Gospel of Mark: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802845030.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yieh, John Yueh-Han (2004). One Teacher: Jesus' Teaching Role in Matthew's Gospel Report. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110913330.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Journal articles

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/306743a0, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/306743a0instead. - Humphreys, Colin J.; Waddington, W. Graeme (March 1985). "The Date of the Crucifixion". Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation. 37: 2–10.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Meeus, Jean (December 2003). "The maximum possible duration of a total solar eclipse". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 113 (6): 343–348. Bibcode:2003JBAA..113..343M.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schaefer, Bradley E. (March 1990). "Lunar Visibility and the Crucifixion". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 31 (1): 53–67. Bibcode:1990QJRAS..31...53S.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1086/132865, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1086/132865instead.

- Web sites

- Espenak, Fred. "Total Solar Eclipse of 0029 Nov 24" (PDF). NASA Eclipse Web Site. NASA. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wallace, Daniel B. (21 June 2004). "Errors in the Greek Text Behind Modern Translations? The Cases of Matthew 1:7, 10 and Luke 23:45". Bible.org. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)