1899 San Ciriaco hurricane

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

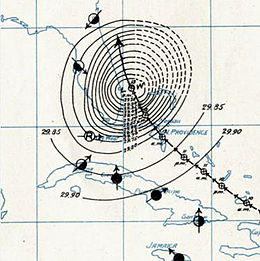

Surface Weather Analysis of Hurricane San Ciriaco on August 13, 1899. | |

| Formed | August 3, 1899 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 12, 1899 |

| (Extratropical after September 4, 1899) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 150 mph (240 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 930 mbar (hPa); 27.46 inHg |

| Fatalities | 3433 direct |

| Damage | $20 million (1899 USD) |

| Areas affected | Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Turks and Caicos Islands, Cuba, Bahamas, East Coast of the United States (Landfall in North Carolina), Atlantic Canada, Azores |

| Part of the 1899 Atlantic hurricane season | |

1899 San Ciriaco hurricane, also known as the 1899 Puerto Rico Hurricane, was the longest-lived Atlantic hurricane on record. The third tropical cyclone and first major hurricane of the season, this storm was first observed southwest of Cape Verde on August 3. It slowly strengthened while heading steadily west-northwestward across the Atlantic Ocean and reached hurricane status by late on August 5. During the following 48 hours, it deepened further, reaching Category 4 on the modern day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale (SSHWS) before crossing the Leeward Islands on August 7. Later that day, the storm peaked winds of 150 mph (240 km/h). The storm weakened slightly before making landfall in Guayama, Puerto Rico with winds of 140 mph (220 km/h) on August 8. Several hours later, it emerged into the southwestern Atlantic as a Category 3 hurricane. The system paralleled the north coast of Dominican Republic and then crossed the Bahamas, striking several islands. Thereafter, it began heading northward on August 14, while centered east of Florida. Early on the following day, the storm re-curved northeastward and appeared to be heading out to sea. However, by August 17, it turned back to the northwest and made landfall near Hatteras, North Carolina early on the following day. No stronger hurricane has made landfall on the Outer Banks since San Ciriaco.

The storm weakened after moving inland and fell to Category 1 intensity by 1200 UTC on August 18. Later that day, the storm re-emerged into the Atlantic. Now heading northeastward, it continued weakening, but maintained Category 1 intensity. By late on August 20, the storm curved eastward over the northwestern Atlantic. It also began losing tropical characteristics and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone at 0000 UTC on August 22, while located about 325 miles (525 km) south of Sable Island. However, after four days, the system regenerated into a tropical storm while located about 695 miles (1,120 km) west-southwest of Flores Island in the Azores on August 26. It moved slowly north-northwestward, until curving to the east on August 29. Between August 26 and September 1, the storm did not differentiate in intensity, but began re-strengthening while turning southeastward on September 2. Early on the following day, the storm again reached hurricane intensity. It curved northeastward and passed through the Azores on September 3, shortly before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone.

In Guadeloupe, the storm unroofed and flooded many houses. Communications were significantly disrupted in the interior portions of the island. Impact was severe in Montserrat, with nearly every building destroyed and 100 deaths reported. About 200 small houses were destroyed on Saint Kitts, with estates suffering considerable damage, while nearly all estates were destroyed on Saint Croix. Eleven deaths were reported on the island. In Puerto Rico, the system brought strong winds and heavy rainfall, which caused extensive flooding. Approximately 250,000 people were left without food and shelter. Additionally, telephone, telegraph, and electrical services were completely lost. Overall, damage totaled approximately $20 million, with over half were losses inflicted on crops, particularly coffee. At the time, it was the costliest and worst tropical cyclone in Puerto Rico. It was estimated that the storm caused 3,369 fatalities. In the Bahamas, strong winds and waves sank 50 small crafts, most of them at Andros. Severe damage was reported in Nassau, with over 100 buildings destroyed and many damaged, including the Government House. A few houses were also destroyed in Bimini. The death toll in the Bahamas was at least 125. In North Carolina, storm surge and rough sea destroyed fishing piers and bridges, as well as sank about 10 vessels. Because Hatteras Island was almost entirely inundated with 4 to 10 feet (1.2 to 3.0 m) of water, many homes were damaged, with much destruction at Diamond City. There were at least 20 deaths in the state of North Carolina. In the Azores, the storm also caused one fatality and significant damage on some islands.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

A tropical storm of unknown origins developed about 480 miles (770 km) southwest of the southwestern-most islands of Cape Verde at 0000 UTC on August 3.[1] According to an article by the United States Hydrographic Office, the British steamship Grangense encountered the system later that day, while located about 1,800 miles (2,900 km) east-southeast of Guadeloupe. According to the ship's log, there was a "sudden change in the weather", falling barometric pressures, and increasingly rough seas. Further, the storm "showed all the symptoms of a genuine West Indian hurricane underdeveloped." The captain, who followed a route from Europe to Brazil for many years, noted that he never experienced "any weather of cyclonic character so far to the eastward before".[2]

Thereafter, the storm strengthened and reached winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) early on August 4. Intensification halted until late on the following day, at which time the storm reached hurricane status. Around 1800 UTC on August 6, it became a Category 2 hurricane. Early the next day, the system deepened to a Category 3. While approaching the Lesser Antilles, it continued to strengthen, reaching Category 4 around midday on August 7. Shortly thereafter, the hurricane passed through the Lesser Antilles and made landfall on Guadeloupe. At 1800 UTC on August 7, the system attained its peak intensity with a maximum sustained wind speed of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 930 mbar (27 inHg),[1] observed by a weather station of Montserrat.[3]

The hurricane weakened slightly while moving west-northward across the Caribbean Sea and made landfall in Guayama, Puerto Rico late on August 8 with winds of 140 mph (220 km/h).[1] August 8 was the namesday of Saint Cyriacus, hence the hurricane's nickname.[4] Several weather stations across the island reported low barometric pressures, with a reading as low as 939 mbar (27.7 inHg) in Guayama. Wind shifts were also experienced across the island, primarily in the south and the west. The storm crossed Puerto Rico in approximately six hours and emerged into the Atlantic Ocean late on August 8, while weakening to a Category 3 hurricane, with winds decreasing to 120 mph (195 km/h). The hurricane would maintain this intensity for more than nine days. Continuing west-northward, the hurricane brushed the north coast of Dominican Republic on August 9. Thereafter, the system moved slowly northwestward through the Bahamas, striking Inagua on August 10 and Andros Island on August 12.[1] According to telephone and telegraph reports from the Weather Bureau, the storm was predicted to make landfall in Florida.[2]

However, the storm instead curved north-northwestward and struck Grand Bahama on August 13.[1] The next day, officials at the Weather Bureau predicted that the hurricane would strike Charleston, South Carolina, at which time it would have weakened "into an ordinary blow".[2] Instead, the storm eventually turned northeastward and moved parallel to the coast of the Southeastern United States for a few days. By early on August 17, however, the hurricane re-curved northwestward. At 0100 UTC on August 18, it made landfall near Hatteras, North Carolina, with winds of 120 mph (195 km/h). Five hours later, the storm weakened to a Category 2 hurricane. Around midday on August 18, it fell to Category 1 hurricane intensity while re-emerging into the Atlantic Ocean. Thereafter, the storm drifted slowly east-northeastward before accelerating to the northeast after 1200 UTC on August 19. It moved parallel to Long Island and New England, until curving just north of due east late on the following day.[1]

The system began losing tropical characteristics after interacting with a weather front and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone early on August 22,[5][1] while situated about 325 miles (525 km) south of Sable Island, Nova Scotia. The extratropical system moved east-southeastward and then southeastward, while continuing to weaken. By August 24, it curved eastward and then northeastward the next day.[1] Operationally, it was believed that the system remained extratropical. However, Partagas (1996) indicated that it regenerated into a tropical storm at 0000 UTC on August 26,[5][1] while located about 695 miles (1,120 km) southwest of Flores Island, Azores. Initially, the rejuvenated system drifted slowly north-northwestward, before turning northward on August 27. No change in intensity occurred for nearly a week. On August 28, it curved northeastward and then eastward, while continuing to drift.[1]

By September 1, the storm began to accelerate and moved east-southeastward. It resumed intensified the next day after curving southeast, and was upgraded to a hurricane early on September 3,[1] based on barometric pressure data.[5] A few hours later, the hurricane attained a secondary peak intensity with a maximum sustained wind speed of 80 mph (130 km/h). Late on September 3, the storm passed through the Azores, shortly before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone. After becoming extratropical, the remnants moved rapidly northeastward and continued to weaken, before dissipating southwest of Ireland late on September 4.[1] However, the Weather Bureau noted that gales prevailed offshore France until September 12, when the system merged with a low pressure area.[6] With 28 days as a tropical cyclone, this system became the longest-lasting Atlantic hurricane on record.

Preparations

On August 7, after stations in the Lesser Antilles reported a change in wind from the northeast to the northwest, the United States Weather Bureau ordered hurricane signals at Roseau, Dominica, Basseterre, Saint Kitts, and San Juan, Puerto Rico; later, a hurricane signal was raised at Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Advisory messages were sent to other locations throughout the Caribbean, including Santo Domingo, Kingston, Jamaica, and Santiago de Cuba, Cuba. Information was also telegraphed to major seaports along the Gulf and East coasts of the United States. On August 9, hurricane signals were posted at Santiago de Cuba, while all vessels bound northward and eastward from Cuba were advised to remain in port.[6]

Impact

Lesser Antilles

While passing through the Leeward Islands, strong winds were reported on several islands.[2] In Guadeloupe, the storm unroofed and flooded many houses and buildings, including the American Consulate in Pointe-à-Pitre.[7] Communications were significantly disrupted in the interior portions of the island. Two schooners sunk and at least 23 flat boats were pushed ashore in the Îles des Saintes archipelago of Guadeloupe.[8] Impact was severe in Montserrat, with nearly every building destroyed. The Courthouse and a school, both of which remained standing, became crowded with homeless women and children. One-hundred deaths and fourteen-hundred injuries were reported. In Saint Kitts, 5-minute sustained winds were 72 mph (116 km/h), while 1-minute sustained winds were as high as 120 mph (190 km/h). About 200 small houses were destroyed on Saint Kitts, with estates suffering considerable damage. Despite the impact, no deaths occurred, which was attributed to ample warnings. Nearly all estates were demolished on Saint Croix, while almost every large building was deroofed. Eleven deaths were reported on the island.[2]

Puerto Rico

The San Ciriaco hurricane was described as the first major storm in Puerto Rico since the 1876 San Felipe hurricane. Approximately 250,000 people were left without food and shelter. Overall, damage totaled approximately $20 million, with over half were losses inflicted on crops, particularly coffee. At the time, it was the costliest and worst tropical cyclone in Puerto Rico. The number of fatalities ranged from 3,100 to 3,400, with the official estimate being 3,369. The San Ciriaco hurricane remains the deadliest tropical cyclone in the history of Puerto Rico.[9]

Strong winds were reported throughout the island, reaching 85 mph (137 km/h) at many locations and over 100 mph (160 km/h) in Humacao, Mayagüez, and Ponce. Within the municipality of Ponce, 500 people died, mostly from drowning. Streets were flooded, waterfront businesses were destroyed, and several government buildings were damaged. Telephone, telegraph, and electrical services were completely lost. Ponce was described as an image of "horrible desolation" by its municipal council. Impact was worst in Utuado, with damage exceeding $2.5 million. In Humacao, 23 inches (580 mm) of rain fell in only 24 hours.[9]

Greater Antilles and Bahamas

In Dominican Republic, heavy rainfall caused the Ozama River to overflow its banks, sweeping away an iron bridge. A freshet was also reported along the Heina River in San Cristóbal Province, washing away many houses.[6]

In the Bahamas, strong winds and waves sank 50 small crafts, a majority of these were located at Andros Island.[6] At Red Bays, two churches were destroyed and many houses were washed away. Several sponging vessels were beached, resulting in an "astronomical" amount of casualties. Only seven homes remained standing at Nicholls Town. A church was demolished along the Staniard Creek. At Coakley Town, several houses were blown down, while a number of vessels sunk. Several schooners, including the Alert, Challenger, Douglass, Eager, Forest Belle, Lealy Lees, Nonsuch, Sloops Complete, Snowbird, Stinging Bee, and Vigilant, were all lost near Andros Island. Additionally, at least 30 other schooners were driven ashore and severely damaged or demolished, including the Admired, Alcia, Beauregard, Equal, Eunice, Experience, Hattie Don, May Queen, Naomi, Rosebud, Seahorse, Traffic, and Victoria; six men were reported missing from the Traffic.[10] About 100 fatalities occurred on Andros Island.[6]

Losses to boating vessels reached $50,000. Within the capital city of Nassau, a fruit factory, a sponge warehouse, a dancing pavilion, and about 100 smaller buildings were destroyed. A few public buildings were damaged, including the Government House. Additionally, a few houses were destroyed in Bimini. The death toll was "conservatively" estimated at 125.[6] On San Salvador Island, two churches and many dwellings were destroyed.

United States and elsewhere

The Weather Bureau office in Jupiter, Florida, recorded sustained winds of 52 mph (84 km/h) and a gusts up to 63 mph (101 km/h). Winds downed all telegraph lines in the area, which disrupted telegraphic communications for about 48 hours. Brief periods of heavy rainfall were also reported.[6] At The Breakers hotel in Palm Beach, storm surge ripped off the upper portion of the ocean deck, which consisted of railings, a canopy, and a flagpole.[11] Between Titusville and Miami, losses reached $5,000. Tides along the coast of South Carolina peaked at 2.8 ft (0.85 m), resulting in no coastal flooding. Well executed warnings were attributed to no fatalities in South Carolina.[6]

Strong winds were observed in coastal North Carolina, with sustained winds up to 93 mph (150 km/h) and gusts as high as 140 mph (230 km/h). However, the anemometer then blew away. According to the Weather Bureau, "the entire island" of Hatteras was submerged in 4 to 10 ft (1.2 to 3.0 m) of water due to storm surge. In only four houses, less than 1 ft (0.30 m) of water was recorded. All fishing piers and equipment were destroyed, while every bridge was swept away. About 10 vessels, including a large steamship, were wrecked. Severe damage also occurred at Diamond City. Among the ships that wrecked was the barkentine Priscilla. Rasmus Midgett, a United States Life-Saving Service member, single-handedly rescued 10 people from the Priscilla. On October 18, Midgett was award the Lifesaving Medal by Secretary of the Treasury Lyman J. Gage.[12] Heavy rains and strong winds as far inland as Raleigh resulted in "great damage" to crops. There were at least 20 fatalities in North Carolina.

Strong winds were also reported in Virginia. At Cape Henry, winds peaked at 68 mph (109 km/h) for five minutes. In Norfolk, five-minute sustained winds reached 42 miles per hour (68 km/h). The storm was quite severe along the James River, with low-lying areas of Norfolk inundated by wind-driven tides, while livestock drowned in the flood waters at Suffolk. A "heavy northeastern storm" began in Petersburg the night of August 17. Corn and tobacco suffered considerable damage as crops were leveled by strong winds.[13]

In the Azores, "several lives were lost" on São Miguel Island. Strong winds and heavy rainfall damaged many houses, inundated several roads, and toppled a number of telegraph poles.

Records

Hurricane San Ciriaco set many records on its path. Killing nearly 3,500 people in Puerto Rico, it was the deadliest hurricane to hit the island and the strongest at the time, until 30 years later when the island was hit by the Hurricane San Felipe Segundo, a Category 5 hurricane, in 1928. It was also the tenth deadliest Atlantic hurricane ever recorded.

Also, with an Accumulated cyclone energy of 73.57, it has the highest ACE of any Atlantic hurricane in history. In 2004, Hurricane Ivan became the second Atlantic hurricane to surpass an ACE value of 70, but did not surpass the San Ciriaco hurricane.

San Ciriaco is also the longest lasting Atlantic hurricane in recorded history, lasting for 28 days (31 including subtropical time).

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e Jose F. Partagas (1996). Year 1899 (PDF). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 43–53. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ^ Christopher W. Landsea (2003). Raw Observations for Hurricane #3, 1899 (XLS). Hurricane Research Division (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ Bailey Ashford (1998) [1934]. A Soldier in Science. New York City, New York: Morrow. ISBN 0-8477-0351-7.

- ^ a b c Jose F. Partagas (1996). Year 1899 (PDF). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 54–64. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h E.B. Garriott (August 1899). Monthly Weather Review (PDF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "West Indian Hurricane; Carried Death and Destruction to Several Islands". The New York Times. Washington, D.C. August 10, 1899. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ "The West India Hurricane". The New York Times. Fort-de-France, Martinique. August 9, 1899. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Stuart B. Schwartz (1992). The Hurricane of San Ciriaco: Disaster, Politics, Society in Puerto Rico, 1899–1901 (PDF). Latin American Studies (Report). Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Wayne Neely (2012). The Great Bahamian Hurricanes of 1899 and 1932. Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse. ISBN 1475925549. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ "Miami Mince Meat". The Miami Metropolis. Miami, Florida. August 18, 1899. p. 1. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Lyman J. Gage (November 13, 1900). Annual Report of the United States Life-Saving Service for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1900. United States Life-Saving Service (Report). Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Treasury. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ David M. Roth (July 16, 2001). Late Nineteenth Century Virginia Hurricanes. Weather Prediction Center (Report). Camp Springs, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

Further reading

- Hairr, John (2008). The Great Hurricanes of North Carolina. Charleston, SC: History Press. pp. 81–104. ISBN 978-1-59629-391-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Schwartz, Stuart B. (1982). "The Hurricane of San Ciriaco: Disaster, Politics, and Society in Puerto Rico, 1899-1901". Hispanic American Historical Review. 72 (3). Duke University Press: 303–334. doi:10.2307/2515987. JSTOR 2515987.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help)

External links

- 1890–1899 Atlantic hurricane seasons

- Category 4 Atlantic hurricanes

- Hurricanes in the Leeward Islands

- Hurricanes in Guadeloupe

- Hurricanes in Îles des Saintes

- Hurricanes in Dominica

- Hurricanes in Montserrat

- Hurricanes in the United States Virgin Islands

- Hurricanes in Puerto Rico

- Hurricanes in the Turks and Caicos Islands

- Hurricanes in the Bahamas

- Hurricanes in North Carolina

- Hurricanes in the Azores

- 1899 meteorology

- 1899 in the United States

- 1899 in Puerto Rico

- 1899 in the Caribbean