Roman temple

Ancient Roman temples were among the most important buildings in Roman culture, and some of the richest buildings in Roman architecture, though only a few survive in any sort of complete state. Today they remain "the most obvious symbol of Roman architecture".[1] Their construction and maintenance was a major part of ancient Roman religion, and all towns of any importance had at least one main temple, as well as smaller shrines. The main room (cella) housed the cult image of the deity to whom the temple was dedicated, and often a small altar for incense or libations. Behind the cella was a room or rooms used by temple attendants for storage of equipment and offerings.

The English word "temple" derives from the Latin templum, which was originally not the building itself, but a sacred space surveyed and plotted ritually.[2] The Roman architect Vitruvius always uses the word templum to refer to the sacred precinct, and not to the building. The more common Latin words for a temple or shrine were sacellum (a small shrine or chapel), aedes, delubrum, and fanum (in this article, the English word "temple" refers to any of these buildings, and the Latin templum to the sacred precinct).

Public religious ceremonies of the official Roman religion took place outdoors, and not within the temple building. Some ceremonies were processions that started at, visited, or ended with a temple or shrine, where a ritual object might be stored and brought out for use, or where an offering would be deposited. Sacrifices, chiefly of animals, would take place at an open-air altar within the templum. Especially under the Empire, exotic foreign cults gained followers in Rome, and were the local religions in large parts of the expanded Empire. These often had very different practices, some preferring underground places of worship, while others, like Early Christians, worshipped in houses.[3]

Some remains of many Roman temples survive, above all in Rome itself, but the relatively few near-complete examples were nearly all converted to Christian churches (and sometimes subsequently to mosques), usually a considerable time after the initial triumph of Christianity under Constantine. The decline of Roman religion was relatively slow, and the temples themselves were not appropriated by the government until a decree of the Emperor Honorius in 415. Santi Cosma e Damiano, in the Roman Forum, originally the Temple of Romulus, was not dedicated as a church until 527. The best known is the Pantheon, Rome, which is however highly untypical, being a very large circular temple with a magnificent concrete roof, behind a conventional portico front.[4]

Architecture

The form of the Roman temple was mainly derived from the Etruscan model, but in the late Republic there was a switch to using Greek classical and Hellenistic styles, without much change in the key features of the form. The Etruscans were a people of unknown origins who arose in northern Italy, which was at its peak in the seventh century BC. The Etruscans were already influenced by early Greek architecture, so Roman temples were distinctive but with both Etruscan and Greek features.[5][6] Surviving temples (both Greek and Roman) lack the extensive painted statuary that decorated the rooflines, and the elaborate revetments and antefixes, in colourful terracotta in earlier examples, that enlivened the entablature.

Etruscan and Roman temples emphasised the front of the building, which followed Greek temple models and typically consisted of wide steps leading to a portico with columns, a pronaos, and usually a triangular pediment above, which was filled with statuary in the most grand examples; this was as often in terracotta as stone, and no examples have survived except as fragments. Especially in the earlier periods, further statuary might be placed on the roof, and the entablature decorated with antefixes and other elements, all of this being brightly painted. However, unlike the Greek models, which generally gave equal treatment to all sides of the temple, which could be viewed and approached from all directions, the side and rear walls of Roman temples might be largely undecorated (as in the Pantheon, Rome and Vic), inaccessible by steps (as in the Maison Carrée and Vic), and even back on to other buildings. As in the Maison Carrée, columns at the side might be half-columns, emerging from ("engaged with" in architectural terminology) the wall.[7]

The platform on which the temple sat was typically raised higher in Etruscan and Roman examples than Greek, with up ten or twelve or more steps rather than the three typical in Greek temples; the Temple of Claudius was raised twenty steps. These steps were normally only at the front, and typically not the whole width of that. It might or might not be possible to walk around the temple exterior inside (Temple of Hadrian) or outside the colonnade, or at least down the sides.[8] The description of the Greek models used here is a generalization of classical Greek ideals, and later Hellenistic buildings often do not reflect them. For example, the "Temple of Dionysus" on the terrace by the theatre at Pergamon (Ionic, 2nd century BC, on a hillside), had many steps in front, and no columns beyond the portico.[9]

After the eclipse of the Etruscan models, the Greek classical orders in all their details were closely followed in the façades of Roman temples, as in other prestigious buildings, with the direct adoption of Greek models apparently beginning around 200 BC, under the late Republic. But the distinctive differences in the general arrangement of temples between the Estruscan-Roman style and the Greek, as outlined above, were retained. However the idealized proportions between the different elements in the orders set out by the only significant Roman writer on architecture to survive, Vitruvius, and subsequent Italian Renaissance writers, do not reflect actual Roman practice, which could be very variable, though always aiming at balance and harmony. Following a Hellenistic trend, the Corinthian order and its variant the Composite order were most common in surviving Roman temples, but for small temples like that at Alcántara, a simple Tuscan order could be used. Vitruvius does not recognise the Composite or Tuscan orders in his writings, which Renaissance writers formalized from observing surviving buildings.[10]

The front of the temple typically carried an inscription saying who had built it, cut into the stone with a "V" section. This was filled with brighly coloured paint, usually scarlet or vermilion. In major imperial monuments the letters were cast in lead and held in by pegs, then also painted or gilded. These have usually long vanished, but archaeologists can generally reconstruct them from the peg-holes, and some have been re-created and set in place.[11]

There was considerable local variation in style, as Roman architects often tried to incorporate elements the population expected in its sacred architecture. This was especially the case in Egypt and the Near East, where different traditions of large stone temples were already millennia old. The Romano-Celtic temple was a simple style, usually with little use of stone, for small temples found in the Western Empire, and by far the most common type in Roman Britain, where they were usually square, with an ambulatory. It often lacked any of the distinctive classical features, and may have had considerable continuity with pre-Roman temples of the Celtic religion.[12]

Circular plans

Romano-Celtic temples were often circular, and circular temples of various kinds were built by the Romans. Greek models were available in tholos shrines and some other buildings, as assembly halls and various other functions. Temples of the goddess Vesta, which were usually small, typically had this shape, as in those at Rome and Tivoli (see list), which survive in part. Like the Temple of Hercules Victor in Rome, which was perhaps by a Greek architect, these survivors had an unbroken colonnade encircling the building, and a low, Greek-style podium.[13]

Different formulae were followed in the Pantheon, Rome and a small temple at Baalbek (usually called the "Temple of Venus"), where the door is behind a full portico, though very different ways of doing this are used. In the Pantheon only the portico has columns, and the "thoroughly uncomfortable" exterior meeting of the portico and circular cella are often criticised. At Baalbek a wide portico with a broken pediment is matched by four other columns round the building, with the architrave in scooped curving sections, each ending in a projection supported by a column.[14]

At Praeneste (modern Palestrina) near Rome, a huge pilgrimage complex of the 1st century BC led visitors up several levels with large buildings on a steep hillside, before they eventually reached the sanctuary itself, a much smaller circular building.[15]

Caesareum

A caesareum was a temple devoted to the Imperial cult. Caesarea were located throughout the Roman Empire, and often funded by the imperial government, tending to replace state spending on new temples to other gods, and becoming the main or only large temple in new Roman towns in the provinces. This was the case at Évora, Vienne and Nîmes, which were all expanded by the Romans as coloniae from Celtic oppida soon after their conquest. Imperial temples paid for by the government usually used conventional Roman styles all over the empire, regardless of the local styles seen in smaller temples. In newly planned Roman cities the temple was normally centrally placed at one end of the forum, often facing the basilica at the other.[16]

In the city of Rome, a caesareum was located within the religious precinct of the Arval Brothers. In 1570, it was documented as still containing nine statues of Roman emperors in architectural niches.[17] Most of the earlier emperors had their own very large temples in Rome,[18] but a faltering economy meant that the building of new imperial temples ceased mostly after the reign of Marcus Aurelius (d. 180), though the Temple of Romulus on the Roman Forum was built and dedicated by the Emperor Maxentius to his son Valerius Romulus, who died in childhood in 309 and was deified.

One of the most prominent of the caesarea was the Caesareum of Alexandria, located on the harbor. During the 4th century, after the Empire had come under Christian rule, it was converted to a church.[19]

Influence

The Etruscan-Roman adaptation of the Greek temple model to place the main emphasis on the main façade and let the other sides of the building harmonize with it only as much as circumstances and budget allow has generally been adopted in Neoclassical architecture, and other classically derived styles. In these temple fronts with columns and a pediment are very common for the main entrance of grand buildings, but often flanked by large wings or set in courtyards. This flexibility has allowed the Roman temple front to be used in buildings made for a wide variety of purposes. The colonnade may no longer be pushed forward with a pronaus porch, and it may not be raised above the ground, but the essential shape remains the same. Among thousands of examples are the White House, Buckingham Palace, and St Peters, Rome; in recent years the temple front has become fashionable in China.[20]

Renaissance and later architects worked out ways of harmoniously adding high raised domes, towers and spires above a colonnaded temple portico front, something the Romans would have found odd. The Roman temple front remains a familiar feature of subsequent Early Modern architecture in the Western tradition, but although very commonly used for churches, it has lost the specific association with religion that it had for the Romans.[21] Generally, later adaptions lack the colour of the original, and though there may be sculpture filling the pediment in grand examples, the full Roman complement of sculpture above the roofline is rarely emulated.

Variations on the theme, mostly Italian in origin, include: San Andrea, Mantua, 1462 by Leon Battista Alberti, which took a four-columned Roman triumphal arch and added a pediment above; San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice, 1610 by Andrea Palladio, which has two superimposed temple fronts, one low and wide, the other tall and narrow; the Villa Rotunda, 1567 on, also by Palladio, with four isolated temple fronts on each side of a rectangle, with a large central dome. In Baroque architecture two temple fronts, often of different orders, superimposed one above the other, became extremely common for Catholic churches, often with the uppermost one supported by huge volutes to each side. This can be seen developing in the Gesù, Rome (1584), Santa Susanna, Rome (1597), Santi Vincenzo e Anastasio a Trevi (1646) and Val-de-Grâce, Paris (1645 on).[22]

An archetypical pattern for churches in Georgian architecture was set by St Martin-in-the-Fields in London (1720), by James Gibbs, who boldly added to the classical temple façade at the west end a large steeple on top of a tower, set back slightly from the main frontage. This formula shocked purists and foreigners, but became accepted and was very widely copied, at home and in the colonies,[23] for example at St Andrew's Church, Chennai in India and St. Paul's Chapel in Manhatten (1766).

Examples of modern buildings that stick more faithfully to the ancient rectangular temple form are only found from the 18th century onwards.[1] Versions of the Roman temple as a discrete block include La Madeleine, Paris (1807), now a church but built by Napoleon as a Temple de la Gloire de la Grande Armée ("Temple to the Glory of the Great Army"), the Virginia State Capitol as originally built in 1785–88, and Birmingham Town Hall (1832–34).[24]

Small Roman circular temples with colonnades have often been used as models, either for single buildings, large or small, or elements such as domes raised on drums, in buildings on another plan such as St Peters, Rome, St Paul's Cathedral in London and the United States Capitol. The great progenitor of these is the Tempietto of Donato Bramante in the courtyard of San Pietro in Montorio in Rome, c. 1502, which has been widely admired ever since.[25]

Though the Pantheon's large circular domed cella, with a conventional portico front, is "unique" in Roman architecture, it has been copied many times by modern architects. Versions include the church of Santa Maria Assunta in Ariccia by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1664), which followed his work restoring the Roman original,[26] Belle Isle House (1774) in England, and Thomas Jefferson's library at the University of Virginia, The Rotunda (1817–26).[27] The Pantheon was much the largest and most accessible complete classical temple front known to the Italian Renaissance, and was the standard exemplar when these were revived.

Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus

The Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill was the oldest large temple in Rome, dedicated to the Capitoline Triad consisting of Jupiter and his companion deities, Juno and Minerva, and had a cathedral-like position in the official religion of Rome. It was destroyed by fire three times, and rapidly rebuilt in contemporary styles. The first building, traditionally dedicated in 509 BC,[28] has been claimed to have been almost 60 m × 60 m (200 ft × 200 ft), much larger than other Roman temples for centuries after, although its size is heavily disputed by specialists. Whatever its size, its influence on other early Roman temples was significant and long-lasting.[29] The same may have been true for the later rebuildings, though here the influence is harder to trace.

For the first temple Etruscan specialists were brought in for various aspects of the building, including making and painting the extensive terracotta elements of the entablature or upper parts, such as antefixes.[30] But for the second building they were summoned from Greece. Rebuildings after destruction by fire were completed in 69 BC, 75 AD, and in the 80s AD, under Domitian – the third building only lasted five years before burning down again. After a major sacking by Vandals in 455, and comprehensive removal of stone in the Renaissance, only foundations can now be seen, in the basement of the Capitoline Museums.[31] The sculptor Flaminio Vacca (d 1605) claimed that the life-size Medici lion he carved to match a Roman survival, now in Florence, was made from a single capital from the temple.[32]

Substantial survivals

Most of the best survivals had been converted to churches (and sometimes later mosques), which some remain. Often the porticos were walled in between the columns, and the original cella front and side walls largely removed to create a large single space in the interior. Rural areas in the Islamic world have some good remains, which had been left largely undisturbed. In Spain some remarkable discoveries (Vic, Cordoba, Barcelona) were made in the 19th century when old buildings being reconstructed or demolished were found to contain major remains encased in later buildings. In Rome, Pula, and elsewhere some walls incorporated in later buildings have always been evident. In most cases loose pieces of stone have been removed from the site, and some such as capitals may be found in local museums, along with non-architectural items excavated, such as terracotta votive statuettes or amulets, which are often found in large numbers.[33] Very little indeed survives from the significant quantities of large sculpture that originally decorated temples.[34]

- Rome

- Pantheon or Temple to All The Gods, unique among Roman temples, but later much imitated. Easily the most impressive and complete interior to survive.

- Temple of Hercules Victor, early circular temple, largely complete

- Temple of Portunus or "Temple of Fortuna Virilis" – very complete Ionic exterior, near Santa Maria in Cosmedin and the Temple of Romulus

- Temple of Romulus – very complete circular exterior, early 4th century, Roman Forum

- Temple of Antoninus and Faustina – the core of the building survives as a church, including parts of the frieze, Roman Forum

- Temple of Hadrian – Campus Martius – a huge wall with 11 columns, now incorporated in a later building

- Temple of Vesta – small circular temple, part complete, Roman Forum

- Temple of Saturn – 8 impressive columns and architrave remain standing, west end of the Roman Forum

- Temple of Bellona (Ostia) – small back-steet all-brick temple at the port.

- Elsewhere

- Palestrina, Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia, (see above) a large complex leading to a small shrine

- Temple of Apollo (Pompeii), unusually, it is the smaller elements that are best preserved, and the surrounding forum

- Temple of Vesta – Tivoli, so-called, circular

- Capitolium of Brixia, Brescia, buried by a landslide and partly reconstructed

- Maison Carrée – Nîmes, Southern France, one of the most complete survivals

- Temple of Augusta and Livia – Vienne, France, exterior largely complete

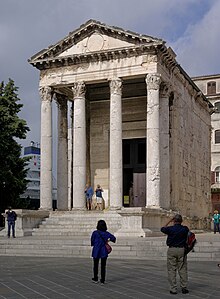

- Temple of Augustus (Pula) – Pula, Croatia, largely complete (illustrated above); a large wall from another temple forms part of the town hall next door.

- Roman Temple of Évora – Évora, Portugal, impressive partial remains of a small temple

- Temple of Jupiter in Diocletian's Palace, Split, Croatia. Small but very complete, amid other Roman buildings, c. 300. Most unusually, the barrel ceiling is intact.

- Roman temple of Alcántara, Spain, tiny but complete

- Roman temple of Vic, Spain. Substantially rebuilt, after it was found covered by a castle.

- Roman temple of Córdoba, Spain. Base and 11 Corinthian columns, found inside later buildings.

- Temple of Bacchus, Baalbek, Lebanon, a famous exotic "Baroque" pilgrimage destination, very largely preserved, including the interior.[35]

- Temples of Jupiter and Venus, Baalbek

- Temple of Artemis (Jerash), Jordan; partial remains of two other temples

- Sbeitla, Tunisia, three small temples in a row on the forum, many other city ruins.

- Dougga, Tunisia, several temples in extensive city ruins, two with substantial remains.

See also

- List of Ancient Greek temples

- Temple for other religious traditions

Notes

- ^ a b Summerson (1980), 25

- ^ Stamper, 10

- ^ Sear

- ^ Wheeler, 104–106; Sear

- ^ Campbell, Jonathan. Roman Art and Architecture – from Augustus to Constantine. Pearson Education New Zealand. ISBN 978-0-582-73984-0.

- ^ Boardman, 255; Henig, 56

- ^ Wheeler, 89; Henig, 56

- ^ Henig, 56, Wheeler, 89

- ^ Cook, R.M., Greek Art, plate 86 and caption, Penguin, 1986 (reprint of 1972), ISBN 0140218661

- ^ Summerson (1980), 8–13

- ^ Henig, 225

- ^ Henig, 56–57; Wheeler, 100–104: Sear

- ^ Wheeler, 100–104; Sear

- ^ Wheeler, 97–106, 105 quoted. Originally the "uncomfortable" junction was screened by a wall, and less apparent.

- ^ Boardman, 256–257

- ^ Henig, 55; Sear

- ^ The statues are all lost, but the base for the statue of Marcus Aurelius survives, and the inscriptions of seven of the nine are recorded in volume 6 of the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum. Jane Fejfer, Roman Portraits in Context (Walter de Gruyter, 2008), p. 86.

- ^ Sear

- ^ David M. Gwynn, "Archaeology and the 'Arian Controversy' in the Fourth Century," in Religious Diversity in Late Antiquity (Brill, 2010), p. 249.

- ^ Heathcote, Edwin, Review of Original Copies: Architectural Mimicry in Contemporary China, by Bianca Bosker, University of Hawaii Press, The Financial Times, January 25, 2013

- ^ Anthony Grafton, Glenn W Most, Salvatore Settis, eds., The Classical Tradition, 927, 2010, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0674035720, 9780674035720, google books

- ^ Summerson (1980), captions to illustrations 21, 41, 42, 72–75

- ^ Summerson (1988), 64–70

- ^ Summerson (1980), 28. The Virginia State Capitol is specifically based on the Maison carre, but in a cheaper Ionic rather than Corinthian.

- ^ Summerson (1980), 25, 41–42, 49–51

- ^ Summerson (1980), 38–39, 38 quoted

- ^ Summerson (1980), 38–39

- ^ Ab urbe condita, 2.8

- ^ Stamper, 33 and all Chapters 1 and 2. Stamper is a leading protagonist of a smaller size, rejecting the larger size proposed by the late Einar Gjerstad.

- ^ Stamper, 12–13

- ^ Stamper, 14–15, 33 and all Chapters 1 and 2; Rykwert, Joseph, The Dancing Column: On Order in Architecture, 357–360, 1998, MIT Press, ISBN 0262681013, 9780262681018, google books; Entry on "Aedes Iovis Optimi Maximi Capitolini" from A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, by Samuel Ball Platner (as completed and revised by Thomas Ashby), Oxford University Press, 1929

- ^ Stamper, 15

- ^ Vickers, Michael, Ancient Rome, Preface, 1989, Elsevier-Phaidon; Henig, 191–199

- ^ Strong, 48

- ^ Wheeler, 93–96

References

- "EERA" = Boëthius, Axel, Ling, Roger, Rasmussen, Tom, Etruscan and Early Roman Architecture, Yale/Pelican history of art, 1978, Yale University Press, ISBN 0300052901, 9780300052909, google books

- Henig, Martin (ed.), A Handbook of Roman Art, Phaidon, 1983, ISBN 0714822140

- Sear, F. B., "Architecture, 1, a) Religious", section in Diane Favro, et al. "Rome, ancient." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed March 26, 2016, subscription required

- Stamper, John, The architecture of Roman temples: the republic to the middle empire, Cambridge University Press, 2005

- Strong, Donald, et al., Roman Art, 1995 (2nd edn.), Yale University Press (Penguin/Yale History of Art), ISBN 0300052936

- Summerson, John (1980), The Classical Language of Architecture, 1980 edition, Thames and Hudson World of Art series, ISBN 0-500-20177-3

- Summerson, John (1988), Georgian London, (1945), 1988 revised edition, Barrie & Jenkins, ISBN 0712620958. (Also see revised edition, edited by Howard Colvin, 2003)

- Wheeler, Mortimer, Roman Art and Architecture, 1964, Thames and Hudson (World of Art), ISBN 0500200211

Further reading

- Claridge, Amanda, Rome (Oxford Archaeological Guides), 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0192880039

External links

- Temple of Hadrian, Rome QuickTime VR

- The Pantheon, Rome QuickTime VR