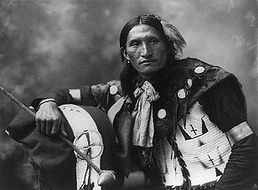

Lakota people

The Lakota (IPA: [laˈkˣota]) (also Lakhota, Teton, Titonwon) are a Native American tribe. They form one of a group of seven tribes (the Great Sioux Nation) and speak Lakota, one of the three major dialects of the Sioux language.

The Lakota are the westernmost of the three Sioux groups, occupying lands in both North and South Dakota. The seven branches or "sub-tribes" of the Lakota are Brulé, Oglala, Sans Arcs, Hunkpapa, Miniconjou, Blackfoot and Two Kettles.

History

The Lakota are closely related to the western Dakota of Minnesota. After their adoption of the horse, šųkáwakhą́ ([ʃũˈkawaˈkˣã]) ('power/mystery dog') in the early 18th century, the Lakota became part of the Great Plains culture with their eventual Algonkin-speaking allies, the Tsitsistas (Cheyenne), living in the northern Great Plains. Their society centered on the buffalo hunt with the horse. There were 20,000 Lakota in the mid-18th century. The number has now increased to about 70,000, of whom about 20,500 still speak their ancestral language. (See Languages in the United States).

After 1720, the Lakota branch of the Seven Council Fires split into two elements, the Saone who moved to the Lake Traverse area on the South Dakota-North Dakota-Minnesota border, and the Oglala-Brulé who occupied the James River Valley. By about 1750, however, the Saone had moved to the east bank of the Missouri, followed 10 years later by the Oglala and Brulé (Sicangu).

The large and powerful Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa villages had prevented the Lakota from crossing the Missouri for an extended period, but when smallpox and other diseases nearly destroyed these tribes, the way was open for the first Lakota to cross the Missouri into the drier, short-grass prairies of the High Plains. These Saone, well-mounted and increasingly confident, spread out quickly. In 1765, a Saone exploring and raiding party led by Chief Standing Bear discovered the Black Hills (which they called the Paha Sapa). Just a decade later, in 1775, the Oglala and Brulé also crossed the river, following the great smallpox epidemic of 1772-1780, which destroyed three-quarters of the Missouri Valley populations. In 1776, they defeated the Cheyenne as the Cheyenne had earlier defeated the Kiowa, and gained control of the land which became the center of the Lakota universe.

Initial contacts between the Lakota and the United States, during the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-06, were friendly. But as more and more settlers crossed Lakota lands, this changed. In Nebraska on September 3, 1855, 700 soldiers under American General William S. Harney avenged the "Grattan Massacre" by attacking a Lakota village, killing 100 men, women, and children. Other wars followed; and in 1862-1864, as refugees from the "Sioux Uprising" in Minnesota fled west to their allies in Montana and Dakota Territory, the war followed them.

Because the Black Hills are sacred to the Lakota, they objected to mining in the area, which has been attempted since the early years of the 19th century. In 1868, the US government signed the Fort Laramie Treaty (1868) with them exempting the Black Hills from all white settlement forever. Four years later, gold was publicly discovered there, and an influx of prospectors descended upon the area, abetted by army commanders like General George Armstrong Custer. The latter tried to administer a lesson of noninterference with white policies, resulting in the Black Hills War of 1876-77.

The Lakota with their allies, the Arapaho and the Cheyenne, defeated the U.S. 7th Cavalry in 1876 at the Battle at the Greasy Grass or Little Big Horn, killing 258 soldiers and inflicting more than 50% casualties on the regiment. But like the Zulu triumph over the British at Isandlwana in Africa three years later, it proved to be a pyrrhic victory. The Teton were defeated in a series of subsequent battles by the reinforced U.S. Army, and were herded back onto reservations, by preventing buffalo hunts and enforcing government food distribution policies to 'friendlies' only. The Lakota were compelled to sign a treaty in 1877 ceding the Black Hills to the United States, but a low-intensity war continued, culminating, fourteen years later, in the killing of Sitting Bull (December 15, 1890) at Standing Rock and the Massacre of Wounded Knee (December 29, 1890) at Pine Ridge.

Today, the Lakota are found mostly in the five reservations of western South Dakota: Rosebud (home of the Upper Sicangu or Brulé), Pine Ridge (home of the Oglala), Lower Brulé (home of the Lower Sicangu), Cheyenne River (home of several other of the seven Lakota bands, including the Sihasapa and Hunkpapa), and Standing Rock, also home to people from many bands. But Lakota are also found far to the north in the Fort Peck Reservation of Montana, the Fort Berthold Reservation of northwestern North Dakota, and several small reserves in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, where their ancestors fled to "Grandmother's Land" (Canada) during the Minnesota or Black Hills War. Large numbers of Lakota also live in Rapid City and other towns in the Black Hills, and in Metro Denver. Lakota elders joined the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO) seeking protection and recognition for their cultural and land rights.

The name Lakota comes from the Lakota autonym, lakhóta "feeling affection, friendly, united, allied". The early French literature does not distinguish a separate Teton division, instead lumping them into a "Sioux of the West" group with other Santee and Yankton bands.

The names Teton and Tintowan comes from the Lakota name thíthųwą (the meaning of which is obscure). This term was used to refer to the Lakota by non-Lakota Sioux groups. Other derivations include: Ti tanka, Tintonyanyan, Titon, Tintonha, Thintohas, Tinthenha, Tinton, Thuntotas, Tintones, Tintoner, Tintinhos, Ten-ton-ha, Thinthonha, Tinthonha, Tentouha, Tintonwans, Tindaw, Tinthow, Atintons, Anthontans, Atentons, Atintans, Atrutons, Titoba, Tetongues, Teton Sioux, Teeton, Ti toan, Teetwawn, Teetwans, Ti-t’-wawn, Ti-twans, Tit’wan, Tetans, Tieton, Teetonwan, etc.

As noted above, the early French sources call the Lakota Sioux with an additional modifier, such as Scioux of the West, West Schious, Sioux des prairies, Sioux occidentaux, Sioux of the Meadows, Nadooessis of the Plains, Prairie Indians, Sioux of the Plain, Maskoutens-Nadouessians, Mascouteins Nadouessi, and Sioux nomades.

Today many of the tribes continue to officially call themselves Sioux which the Federal Government of the United States applied to all Dakota/Lakota/Nakota people in the 19th and 20th centuries. However, some of the tribes have formally or informally adopted traditional names: the Rosebud Sioux Tribe is also known as the Sicangu Oyate (Brulé Nation), and the Oglala often use the name Oglala Lakota Oyate, rather than the English "Oglala Sioux Tribe" or OST. (The alternate English spelling of Ogallala is not considered proper.) The Lakota have names for their own subdivisions.

Notable persons include Tatanka Iyotake from the Hunkpapa band and Tasunka witko, Makhpyia-luta, Hehaka Sapa and Billy Mills from the Oglala band

Readers may want to consider that recently a body of evidence has shown that TASUNKA WITCO was Minneconjou. [citation needed]

Reservations

Today, one half of all Enrolled Sioux live off the Reservation.

Lakota reservations recognized by the US government include:

- Oglala (Pine Ridge Indian Reservation)

- Brulé (Rosebud Indian Reservation)

- Hunkpapa (Standing Rock/Cheyenne River)

- Miniconju (Cheyenne River)

- Sans Arc (Cheyenne River)

- Two-Kettle (Cheyenne River)

- Santee

- Yanktonai (Yankton)

- Flandreau

- Sisseton-Wahpehton

- Lower Sioux

- Upper Sioux

- Shakopee

- Prairie Island

See also

A starship, the USS Lakota, was named for them in the Star Trek universe.

External links

- The Teton Sioux (Edward S. Curtis)

- Lakota Language Consortium

- Lakota Winter Counts a Smithsonian exhibit of the annual icon chosen to represent the major event of the past year

Bibliography

- Christafferson, Dennis M. (2001). Sioux, 1930-2000. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 821-839). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- DeMallie, Raymond J. (2001a). Sioux until 1850. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 718-760). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- DeMallie, Raymond J. (2001b). Teton. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 794-820). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- Hein, David (Advent 2002). "Episcopalianism among the Lakota / Dakota Indians of South Dakota." The Historiographer, vol. 40, pp. 14-16. [The Historiographer is a publication of the Historical Society of the Episcopal Church and the National Episcopal Historians and Archivists.]

- Hein, David (1997). "Christianity and Traditional Lakota / Dakota Spirituality: A Jamesian Interpretation." The McNeese Review, vol. 35, pp. 128-38.

- Parks, Douglas R.; & Rankin, Robert L. (2001). The Siouan languages. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 1, pp. 94-114). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.