User:Parkwells/Jefferson-Hemings controversy

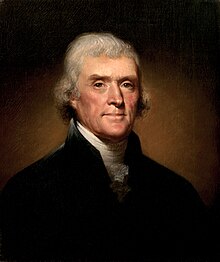

Thomas Jefferson | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale, 1800 | |

| 3rd President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1801 – March 4, 1809 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 13 [O.S. April 2] 1743 Shadwell, Virginia |

| Died | July 4, 1826 (aged 83) Charlottesville, Virginia |

| Spouse | Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson |

The Jefferson-Hemings controversy was related to questions for nearly 200 years as to whether United States President Thomas Jefferson had a long-term sexual relationship with his mixed-race slave Sally Hemings and fathered six children by her. When the claim was reported by political opponents in 1799, 1802 and later, Jefferson did not respond publicly. His descendants and various biographers of the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries defended him, with denial of the pervasiveness of interracial relationships, especially among white masters and enslaved women. It resulted in many mixed-race "white" slaves in colonial and antebellum American society. The prevalence of the relationships and mixed-race descendants was commented on by contemporary women writers[1], foreign visitors[2], and numerous slave narratives published before the American Civil War, as well as African-American writers following the war. Since the mid-twentieth century, United States historians have more thoroughly studied and documented this issue.

In 1873 Hemings' son Madison published a memoir in an Ohio newspaper, claiming Jefferson as father and recounting his family experiences at Monticello, including the promise Jefferson made to Sally Hemings to free her children. His account of paternity was confirmed by Israel Jefferson, a former slave at Monticello, in an interview in the same paper that year. Thomas Jefferson supporters generally discounted both interviews; they focused on political opponents' reasons for publication, rather than the details which could be confirmed independently. For instance, the Hemings family was the only one in which all members gained freedom, either before or after Jefferson's death. Madison's sister Harriet was the only female slave whom Jefferson allowed to be free in his lifetime.

The historiography of the issue shows that until the last quarter of the 20th century, prominent historians generally discounted and dismissed stories of Jefferson's "shadow family" (as such mistresses and children were called) by Hemings. They based this on two adult Jefferson grandchildren identifying the Carr brothers as father(s), ideas about Jefferson's character and personality, and Jefferson's bias against blacks expressed in his writings. (They failed to note that Sally Hemings was described as "highly attractive", was half-sister to his late wife, and was of three-quarters European ancestry.) Historians did not re-examine the original sources and note the conflicting evidence and errors of family testimony, but for 180 years pointed to the Carrs as the likely father(s) of Hemings children.

In the late 20th century, a few historians began to re-examine the body of evidence related to the allegations and differing testimony. A timeline showed that Hemings only conceived when Jefferson was in residence at Monticello, and a statistical analysis of the data in 2000 concluded there was a 99 percent chance he fathered all her children. A 1998 DNA analysis showed a descendant of Hemings had a match to the Y-chromosome of the Jefferson male line, and conclusively showed there was not a match between the Carr line and the Hemings line.

Most historians have come to acknowledge that Jefferson had the 38-year relationship and fathered all of Hemings' children. Four survived to adulthood. Seven-eighths European by ancestry and legally white by Virginia law of the time, they eventually moved North as adults: three became part of "white" society, as were their descendants. Additional descendants in later generations were known to enter white society. In 2010 three descendants of Thomas Jefferson were honored with the international "Search for Common Ground" award. They had reached across the divisions in the family between the Wayles-Jefferson and Hemings-Jefferson lines to heal "the legacy of slavery".[3] They have founded "The Monticello Community" to recognize the descendants of all the people who lived and worked at the plantation.[3]

Historiography

[edit]"The ability of whites to deny reality was legendary: 'Every lady tells you who is the father of all the mulatto children in everybody's household,' Civil War diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut famously observed, 'but those in her own she seems to think drop from the clouds'."[1]

"The circumstance, then, that Thomas Jefferson should become a father by one of his own slaves, derives any unusual interest from his position in social and public life other than the occurrence in itself considered. Such things characterized slavery as long as it lasted." -- Judge Sibley, 1902, Scioto Gazette (Ohio) [4]

"The story of the Jefferson-Hemings relationship is part of an ongoing national conversation on race, sexuality, and American culture. One of the questions it forces historians to address today is: have we consistently ignored these issues in an effort to "whitewash" our national history? Have we excluded discussions of race and sexuality in an effort to make our historical memory conform to a Jeffersonian rhetoric of equality?" --Andrew O. Boulton, William and Mary Quarterly, 2001[5]

Background

[edit]In 1772 Thomas Jefferson married the young widow Martha Wayles Skelton, the daughter of John Wayles and Frances. They had six children, of whom only two daughters survived to adulthood, and the younger died at age 25.

After his father-in-law John Wayles died in 1773, Thomas Jefferson (through his wife) inherited his estate, including more than 100 slaves. Among them were Betty Hemings, a mixed-race woman, and her 10 children. Historians believe the six younger ones were fathered by the widower Wayles, who took Hemings as a concubine in 1761 after being widowed for the third time, and kept her in that role for the remainder of his life (12 years).[6] The six were three-quarters European in ancestry and half-siblings to Jefferson's wife. As their mother was a slave, they were all born into slavery by the principle of partus sequitur ventrum, incorporated into Virginia law since 1662.[7][8] The youngest was Sally Hemings. The Hemings's children were trained for privileged positions at Monticello, working closely with the Jeffersons as domestic servants, valet and butler, nursemaids, chefs, artisans and highly skilled craftsmen who did the finest woodworking, ironwork, etc.

Martha Wayles Jefferson died in 1783 after eleven years of marriage, when Jefferson was 40. He promised her on her deathbed that he would never remarry.

Sally Hemings was never known to marry or have a relationship with another slave. Contemporary testimony said she was faithful to the father of her children.[9]. She had six mixed-race children who were very fair and said to strongly resemble Jefferson. They were:

- Harriet I, died young

- Beverly (also called William Beverley)

- Harriet II

- unnamed daughter (possibly Thenia), who died at birth

- Madison (his full name was James Madison)

- Eston (full name was Thomas Eston)

Controversy

[edit]"Through his celebrity as the eloquent spokesman for liberty and equality as well as the ancestor of people living on both sides of the color line, Jefferson has left a unique legacy for descendants of Monticello's enslaved people as well as for all Americans."[10]

Sally Hemings and her children

[edit]Historians now widely accept that as a widower, Jefferson had a 38-year intimate relationship with his mixed-race slave Sally Hemings, and had six children by her.[11] In that historical period, the Hemingses would have been called a "shadow family". Hemings was three-fourths white and a half-sister to Jefferson's late wife, as her father was also John Wayles. As a widower, Wayles had six children by a 12-year relationship with his slave concubine Betty Hemings. The youngest was Sally.

Hemings' children by Jefferson were seven-eighths European in ancestry and legally white according to Virginia law of the time. (The "one-drop rule" did not become part of law until 1924.) Of the four who survived to adulthood: William Beverley, Harriet, James Madison and Thomas Eston Hemings, all but Madison eventually identified as white and lived in white communities as adults. Thomas Jefferson Randolph, the president's oldest grandson, was among those who noted the Hemings' children's strong resemblance to his grandfather.[12]

Controversy

[edit]As early as the 1790s, neighbors talked about Jefferson's apparent relationship with Hemings. Visitors wrote about the light-skinned slave children's resembling the master.[13] In 1802 the journalist James T. Callender reported in a Richmond paper that Jefferson had fathered several children with Sally Hemings, and violated the unspoken rule in the South against discussing the many mixed-race children of slaves who obviously were of European as well as African descent.

Jefferson never responded publicly and preserved his privacy. He exercised discretion, which was all that Southern society required.[14]

His family later led the denials. His daughter Martha told her oldest son that Jefferson had been away from Monticello for more than a year before Eston Hemings was born and asked him to protect his grandfather's reputation. Thomas Jefferson Randolph identified Peter Carr, Jefferson's nephew, as father of the Hemings children. The biographer Henry Randall accepted this family testimony (told him by Randolph) and passed it on in a letter to the historian James Parton, while claiming to have seen supporting records on Jefferson's absence. (There were no such records.) Randall also attested that Randolph had been managing Monticello years before he did, as adding to his authority to comment on events at the plantation. Randall's letter became a "pillar" of historians' "defenses" of Jefferson.[15]

In 1873 Madison Hemings published his memoir claiming Jefferson as father and telling of life at Monticello. His mother had told him her relationship with Jefferson began when she was working in his household in Paris. To persuade her to return to the US, Jefferson promised to free her children when they came of age.[16] At the time and again in the 1950s, when the memoir was rediscovered, historians attacked the style of Hemings' account, his claim, and the political intentions of the journalist; they essentially discounted the content. (The 20th century historian Merrill Peterson noted it was accurate in many respects.) That year Israel Jefferson, another former slave of Monticello, confirmed the account of Jefferson's paternity of Hemings' children in his own memoir, published in the same newspaper.

The family's Carr paternity thesis and assertion of Jefferson's critical absence were both repeated by the biographer James Parton in his 1874 book on the president.[17][18] Parton influenced succeeding 20th-century historians, such as Merrill Peterson and Douglass Adair. Peterson characterized Randall's statements in a way that increased his "power as a source."[19] In turn, they were relied on by Dumas Malone. In the 1970s in one of his books, Malone was the first to publish a letter by Ellen Randolph Coolidge, Randolph's sister, claiming that Samuel Carr had fathered Hemings' children.

Briefly, 20th-century supporters defended Jefferson against the allegation of the liaison on the following grounds: he was absent at the conception of one child; Jefferson descendants had identified Peter and/or Samuel Carr as father(s), and the Jefferson grandchildren strongly denied Jefferson's paternity[20]); Jefferson's character and personality would not allow such actions (although the prevalence of such arrangements among planters was widely known); and Jefferson's known antipathy to blacks. They discounted evidence from former slaves, including Madison Hemings, questioning his motivation and writing style, and using negative stereotypes in characterizing his intent.[21]

Facts

[edit]- In 1968 and 1974 historians used the timeline of Jefferson's activities developed by Dumas Malone to show that Jefferson was at Monticello at the time of conception of each of Hemings' children, during a 15-year period when he was often away for several months at a time. Hemings conceived only when Jefferson was at Monticello. These facts contradicted the family testimony of his daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph and her children.[22][23][24][25]

A statistical study of the relation of Jefferson's visits and Hemings' conceptions showed there was only a 1% chance that someone other Jefferson was the father - and that would have had to be someone with equal access, for which there is no historical evidence.[26]

- The Hemings children were named for people in the Randolph-Jefferson family or important to Jefferson.[27] This was typically a sign of relation to the white family - Rothman and Edward Ball

- Jefferson gave the Sally Hemings family special treatment: They did not start apprenticeships in trades until the age of 14. The three boys were each apprenticed to the master carpenter of the estate, the most skilled artisan.[28]

- Most importantly, Jefferson freed all the Hemings children, the only slave family who all went free from Monticello. Harriet Hemings was the only female slave he allowed freedom; the remainder of the few slaves whom Jefferson freed from the hundreds he owned were male.[29]

- Check TJHS claim of all Hemings sons and grandsons whom Jefferson still owned - distinction between men who had given him decades of service and the young Hemings.

- He allowed Beverley (male) and Harriet to "escape" in 1822 at ages 23 and 21, although Jefferson was already struggling financially and would be $100,000 in debt at his death four years later. Harriet Hemings was the only female slave he allowed to go free.[30] Jefferson had his overseer Edmund Bacon provide Harriet with $50 (then equal to three days' wages) for her journey North (as confirmed in Bacon's memoir). This avoided publicity but meant that the young adults were legally fugitive slaves until Emancipation. Their absences were noted and talked about among the gentry of the area.[29][31]

- In his 1826 will, Jefferson freed their younger brothers Madison and Eston Hemings. His petition to the legislature was granted to give permission for them and three older Hemings males, who had already served Jefferson for decades and were also freed in his will, to stay in the state where their families lived. (He did not free their wives and children, and some families were split up at sale.) The will and petition were publicly known.[32] Shortly after Jefferson's death, his daughter Martha Randolph gave Sally Hemings "her time", an informal freedom. She lived with her two freed sons in nearby Charlottesville for nearly a decade until her death.[29]

In 1997 Annette Gordon-Reed demonstrated that many historians had failed to assess critical evidence. She identified the errors of fact in family testimony which earlier historians failed to note, as well as gaps and errors in the overseer Bacon's account. Bacon was not at Monticello during some of the period for which he commented on events. She also noted the significance of Jefferson's numerous actions related to the Sally Hemings' family, as noted above, which he took for no other slave family.[33]

- EMPHASIZE: For 180 years, historians represented Peter or Samuel Carr as the likely father(s) of Sally Hemings' children. This was conclusively disproved in the 1998 DNA study of the Y-chromosome of direct male descendants of the Jefferson male line, the Carr line, and an Eston Hemings descendant.[34] In the same study, the team did find a match between the Eston Hemings descendant and the Jefferson male line.[34][35]

Conclusions

[edit]With this new evidence, formerly skeptical biographers such as Joseph Ellis and Andrew Burstein publicly stated their being convinced of Jefferson's paternity of Hemings' children.[36] Burstein later said,

[T]he white Jefferson descendants who established the family denial in the mid-nineteenth century cast responsibility for paternity on two Jefferson nephews (children of Jefferson’s sister) whose DNA was not a match. So, as far as can be reconstructed, there are no Jeffersons other than the president who had the degree of physical access to Sally Hemings that he did.[37]

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which operates Monticello, the major public history site on Thomas Jefferson, issued its own report in 2000, concluding there was a high probability that Jefferson fathered Eston Hemings and most likely all of Hemings' children. When announcing the results of the report, Dr. Daniel P. Jordan, president of Monticello, said the Foundation was undertaking to incorporate "the conclusions of the report into Monticello’s training, interpretation, and publications." New articles and monographs on Hemings descendants have been published by the Foundation, and they have installed exhibits showing Jefferson as the father of all of Sally Hemings' children.[38][39]

Numerous articles and books published since 2000 have reflected the new consensus, for instance: Lucia C. Stanton, Free Some Day: African American Families at Monticello (2000); Joshua D. Rothman, Notorious in the Neighborhood: Sex and Interracial Relationships in Virginia, 1787-1861 (2003); Philip D. Morgan, "Interracial Sex In the Chesapeake and the British Atlantic World c. 1700-1820", in Sally Hemings & Thomas Jefferson: History, Memory, and Civic Culture, edited by Jan Lewis, Peter S. Onuf, (2003); Annette Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family (2007); Gordon Wood, Empire of Liberty (2009); and Jack Rakove, Revolutionaries: A New History of the Invention of America (2010).

Some historians continued to disagree with these conclusions. For instance, in 1999 the newly formed Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society (TJHS) commissioned its own report. Its Scholars Commission concluded in 2001 that there was insufficient evidence to think that Jefferson was the father of Hemings's children. It suggested that his brother Randolph Jefferson was the father, and also suggested that Hemings may have had multiple partners for her children.[40]

Critics of the report noted Randolph Jefferson had never been seriously proposed as a candidate until after the DNA study of 1998 showed a match with the Jefferson male line. Andrew O. Boulton noted, "previous testimony had agreed" that Hemings had only one father for her children.[9] A team of researchers documented that Randolph Jefferson was seldom at Monticello and published their article in Heritage Quest Magazine.[41]

The National Genealogical Society also had a review of the evidence and devoted the fall 2001 issue of its quarterly to the Jefferson-Hemings issues. Articles by genealogist Helen F.M. Leary and others criticized the TJHS Scholars Report for failing to adhere to the standards of genealogical research, which the NGS authors characterized as more stringent than the legalistic paradigm adopted by the commission. Specifically, the genealogist Helen F. M. Leary noted that the Scholars Commission's failings included: over-reliance on derivative sources, biased assessment of data, distortion of evidence, deficient context, and, most importantly, ignoring the weight of the body of evidence.[42] Leary concluded that "the chain of evidence securely fastens Sally Hemings's children to their father, Thomas Jefferson."[43][44]

The Monticello Association, a private lineage society of descendants of Martha Wayles and Thomas Jefferson, commissioned its own report in 1999. It was trying to decide whether to admit Jefferson-Hemings descendants as members. Based on its report of 2002, which addressed whether Hemings descendants could meet its documentation requirements and assessed current evidence for Jefferson's paternity, most members voted that year against admission of Hemings' descendants.[45] Some Wayles-Jefferson descendants, unhappy with the Association, have joined Hemings-Jefferson descendants in separate reunions beginning in 2003. As John Works, Sr., a member of the Association who supported the full family reunion, said, “Nobody has proof, really, of direct descendancy to Thomas Jefferson.”[45]

Legacy

[edit]In 2010 Shay Banks-Young and Julie Jefferson Westerinen, African-American and white descendants, respectively, of Hemings-Jefferson, were honored together with David Works, a descendant of Wayles-Jefferson, with the international "Search for Common Ground" award for "their work to bridge the divide within their family and heal the legacy of slavery."[3] They have been featured on NPR and in numerous interviews and appearances across the country.[3] They have organized "The Monticello Community", to bring together descendants of all the people who lived and worked there during Thomas Jefferson's lifetime.[46]

==

[edit]Beginning in the 1790s, Jefferson's neighbors began to talk about rumors of his relationship with a slave and children by her. One paper ran an article in 1799. In 1802 the journalist James T. Callender wrote in the Richmond Recorder that Jefferson had fathered several children with his slave Sally Hemings. Jefferson never responded publicly. Political opponents of Jefferson publicized the allegations, which received sensational coverage by newspapers across the country.[47][48] Periodically the story would be revived; his Wayles descendants denied it.

1. According to the 19th-century biographer Henry Randall, Thomas Jefferson Randolph (the oldest grandson of Jefferson) and others told him that Hemings had been the mistress of Jefferson's nephew Peter Carr.[49][50] Thomas' sister Ellen Randolph Coolidge wrote that Hemings's children were fathered by Peter's brother Samuel Carr.[51] This representation by the Jefferson descendants that one or both of the Carrs was responsible for Hemings' children was adopted by numerous historians to explain the Hemings' children resemblance to Jefferson and provide an alternate father.

- Fact: The 1998 DNA study conclusively disproved any connection between the Carr line and that of Eston Hemings' male descendant.[34]

The historian Andrew Burstein has criticized those supporting new candidates for paternity:

"[T]he white Jefferson descendants who established the family denial in the mid-nineteenth century cast responsibility for paternity on two Jefferson nephews (children of Jefferson’s sister) whose DNA [in 1998] was not a match. So, as far as can be reconstructed, there are no Jeffersons other than the president who had the degree of physical access to Sally Hemings that he did."[37]

2. Randall also relied on Randolph's saying (based on a letter from his mother Martha Jefferson Randolph) that Jefferson had been gone from Monticello for more than a year prior to the birth of one of Hemings' children, making his paternity impossible. He claimed to have seen supporting records.[50]

- Fact: Jefferson was at Monticello at the time of conception of each of Heming's children, as shown by the historian Dumas Malone's timeline of his activities. This tracked his travels including during a 15-year period when he was frequently away from the plantation for several months at a time. Hemings never conceived a child when Jefferson was not there.[52][53] No other man was documented to have such access. It has been shown that Randall claimed records where none existed.[54]

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation notes these facts as being widely agreed upon:

- Thomas Jefferson was at Monticello at the conception times of Sally Hemings' six known children. There are no records suggesting that she was elsewhere at these times, or records of any births at times that would exclude Jefferson paternity.

- People familiar with Monticello never said that Sally Hemings' children had different fathers.

- Sally Hemings' children were light-skinned, and three of them (daughter Harriet and sons Beverley and Eston) lived as members of white society as adults.

- According to contemporary accounts, including by his grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph, Sally Hemings' children strongly resembled Thomas Jefferson.

- Thomas Jefferson freed all of Sally Hemings' children: Beverly and Harriet were allowed to leave Monticello in 1822; Madison and Eston were freed when they came of age by Jefferson's 1826 will. Jefferson gave freedom to no other nuclear slave family and no other slave woman.

- Thomas Jefferson did not free Sally Hemings. His daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph gave Hemings "her time" and permitted her to leave Monticello not long after Jefferson's death; she lived in Charlottesville for the rest of her life with her sons Madison and Eston.

- Several people close to Thomas Jefferson or the Monticello community believed that he was the father of Sally Hemings' children.

- Eston Hemings changed his name to Eston Hemings Jefferson in 1852.

- Madison Hemings stated in 1873 that he and his siblings Beverly, Harriet, and Eston were Thomas Jefferson's children.

- The descendants of Madison Hemings who have lived as African Americans have passed a family history of descent from Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings down through the generations.

- Eston Hemings' descendants, who have lived as whites, have passed down a family history of being related to Thomas Jefferson. In the 1940s, family members changed this history to say that an uncle of Jefferson's, rather than Jefferson, was their ancestor.[55] They feared racial discrimination against their children. Since the publication of the Brodie book and revelation of past family decisions, the Eston Hemings Jefferson descendants have renewed their family history of connection to Thomas Jefferson, confirmed by the DNA results.

3. In 1873, Madison Hemings published his memoir in an Ohio newspaper, claiming Jefferson as his father and Hemings as his mother. Israel Jefferson, another former Monticello slave interviewed by the same reporter, confirmed Hemings' account that year. Madison noted that his surviving three siblings had all entered white society by then, according to their appearance, and two had married white partners of good circumstances.

- Critics asserted that Madison's memoir exhibits a vocabulary unlikely to be used by a former slave, betraying the hand of the editor Wetmore, a Republican partisan and abolitionist.

- Response: Gordon-Reed noted the bias of historians' assumptions about what an ex-slave "should" sound like, leading them to discount the facts of his statement, as well as to ignore the likely influence of the Hemingses having worked closely with the educated Jeffersons.[56]

- Some critics proposed that Hemings' 1873 memoir was based on Callender's articles, as both included the same misspelling of the name of Martha Jefferson's father, John Wayles.[51]

- Response: Other historians note that such a transcription of "Wayles" to "Wales" is an error easily reproduced independently.

- A rival newspaper wrote, "We have no doubt but there are at least fifty negroes in this county who lay claim to illustrious parentage. This is a well known peculiarity of the colored race."[57]

- Response: Historians and journalists since the mid-20th century, such as Peter Kolchin, Nell Irvin Painter, Joshua D. Rothman and Edward Ball, have documented the prevalence of interracial relationships among planters (many of them prominent politicians and leaders in the South) and enslaved women, with resulting mixed-race children, as did white women writers in the mid-nineteenth century, such as Mary Chesnut and Fanny Kemble, and numerous escaped men and women in slave narratives. In 1860, most of the 200 paying students at Wilberforce College, founded for black students, were the mixed-race children of wealthy southern planters and their mistresses of color.[58]

- Some historians criticized the lack of oral tradition predating the 1873 memoir; however, oral traditions tend not to leave evidence until written down.

- Response: Since most of the Hemings descendants had identified as white, and until 1865 Beverly and Harriet Hemings were legally fugitive slaves, they shared an imperative to leave no record.[23][9]

- Madison had some factual errors. Critics claimed he could not write about events in his claimed parents' lives before he was born or when too young to understand.

- Response: The historian Annette Gordon-Reed noted these aspects, but also cross-checked the details of Hemings' account. She found his evidence supported by other documentation and generally more reliable than competing accounts by Jefferson's descendants, or by Edmund Bacon.[59]

9. According to a 1902 article, neighbors of Madison and Eston Hemings in Chillicothe, Ohio attested to general knowledge in the 1840s of the men's descent from the former president.[60]

10. When the Hemings' and Jefferson memoirs were rediscovered in the 1950s, notable historians such as Merrill D. Peterson and Douglass Adair generally discounted the accounts by former Monticello slaves, believing their publication to have been politically motivated by Jefferson's enemies. Their dismissal influenced historians who followed them, such as Dumas Malone, who did not re-evaluate the original contrasting testimonies from the family and data that supported Hemings' account.[54]

11. In 1968 Winthrop Jordan wrote a study of American race relations, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550-1812, in which he noted the account of Jefferson and Hemings as part of his groundbreaking discussion of interracial sex. Based on the biographer Dumas Malone's timeline, Jordan noted that Jefferson had been at Monticello at the time each of Hemings' children was conceived.[61]

12. In 1974 Fawn McKay Brodie's biography of Jefferson was the first to fully investigate the possible relationship of Jefferson with Hemings. She also used the biographer Dumas Malone's timeline to establish Jefferson's presence at Monticello for each of Hemings' conceptions, to correct for the errors in his descendants' 19th-century testimonies.[23]

- Response: Because of her psychological analysis of Jefferson, Brodie's work was largely discounted by notable Jefferson specialists. Malone rejected the idea of Jefferson's relationship with Hemings based on his "character".[62][63] Prominent historians continued to publish biographies discounting the Hemings story, such as Joseph Ellis in his 1993 award-winning book, American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson.

13. In 1997 Annette Gordon-Reed published Thomas Jefferson & Sally Hemings: An American Controversy, in which she examined the way historians had assessed and used evidence on this issue. She showed how they had allowed their biases and interest in defending Jefferson to affect how they assessed the evidence. For example, Hemings's statement about his father was labeled unreliable "oral history", while the accounts passed down in the Jefferson family were treated as trustworthy, although the family testimony was self-contradictory and not supported by the existing documentary record.

She identified additional circumstantial facts that supported Madison Hemings' claim of Jefferson's paternity for him and his siblings, especially Jefferson's special treatment of the Hemings slave family, which was different from that of any other slave family. He satisfied what Hemings said was Jefferson's agreement with Sally, as he set all her children free, although it was at a time when he was under increasing financial pressures, and he died $100,000 in debt.[64]

- the Hemings sons were named after people in the Randolph-Jefferson family tree and friends with connection to Jefferson, rather than for people in the Hemings family;

- contemporaries, including his grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph, noted the strong resemblance of some of the Hemings' children to Jefferson;

- the Hemings children were given privileged treatment in terms of their training and work assignments;

- Jefferson officially freed only two slaves during his lifetime, both Sally's brothers: Robert (who purchased his freedom) and James Hemings;

- Jefferson allowed two of Hemings' children, Beverley (male) and Harriet, to "escape" in 1822, after they reached the age of 21. He did not try to recapture them, as he had other slaves who escaped, and his overseer gave Harriet money for her journey;

- Harriet Hemings is the only female slave whom Jefferson allowed freedom during his lifetime;

- Jefferson freed only five slaves in his will, all Hemings males (including Sally Hemings' two youngest sons, then under age);

- Jefferson's daughter gave Sally Hemings "her time", an informal freedom that allowed her to live freely with her sons in Charlottesville after they gained freedom as adults; and

- the Hemings nuclear family was the only slave family of Monticello to have all its members achieve freedom.

These facts are also included in the report issued by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation following results of the 1998 DNA study below. The Foundation Committee concluded that Jefferson was highly likely the father of Eston Hemings, and likely of all Sally's children.[65]

Academic debate

[edit]In his monumental history of early American race relations, White Over Black (1968), Winthrop Jordan treated the Hemings-Jefferson link as plausible and worthy of consideration He noted that Jefferson was at Monticello every time Sally Hemings became pregnant, although he was frequently away from Monticello for several months at a time. He based this conclusion on the well-documented timeline of his activities developed by Dumas Malone in his multi-volume biography.

Malone, Douglass Adair, Virginius Dabney, and other authors rebutted Brodie's argument by relying on the Jefferson family's statements about the Carr brothers as father(s), but did not cross-check their evidence.

In 1997, law professor Annette Gordon-Reed published an examination of the arguments and available evidence in Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy. She pointed out that most historians had used double standards to evaluate the evidence for and against the statement of Madison Hemings. For instance, they had accepted family testimony from white descendants of Jefferson, while claiming that Madison Hemings' memoir was based on oral history and unreliable. Gordon-Reed did not argue that documentary records proved Madison Hemings's claim, only that authors had unfairly dismissed it and overlooked inconsistencies in Jefferson family claims. She analyzed and summarized the many ways that Jefferson had treated the Sally Hemings family in a way distinct from his treatment of other slaves: most importantly, he freed all her children, even as he was sinking deeper in debt.

Other claims

[edit]Descendants of Thomas C. Woodson have published claims that he was Sally Hemings's son by Thomas Jefferson. They say he was born at Monticello in 1790, and was the child "Tom" referred to in Callender's articles.[66] The first-known documentary evidence of Woodson was a record of him by name as a free man of color in Greenbrier County, West Virginia, in 1807. He was a farmer, married and had a child.

- Fact: It is uncertain if Sally Hemings had her first child in 1790, as there is no record of it; Jefferson started the Farm Book in 1794. Madison Hemings said she had a child about this time who died as an infant. The 1998 DNA study conclusively disproved any connection between the Woodson descendants (five were tested) and the Jefferson male line. The Woodsons did show European ancestry in the paternal line.[34]

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation Research Committee report of January 2000 (see below) states, "If a child born in 1790 survived infancy, its absence from the Farm Book in 1794 and succeeding years is hard to explain." No surviving child of Sally Hemings was documented as born before 1795. The report does not address the partial erasure of the name of a boy born in 1790, which appears on page 31 of the Farm Book.[67] The report found the Woodson family claims improbable. "If Thomas C. Woodson was Sally Hemings’s son born in 1790, he would have been a father at sixteen and a landowner at seventeen; his wife would have been eight years older than he. While this is not necessarily impossible, it would have been highly unusual."[68] In 2001, the National Genealogical Quarterly special issue about the Jefferson-Hemings controversy placed Woodson's birth date circa 1784-85, based on later census data.

DNA analysis

[edit]John Wayles Jefferson | |

|---|---|

Grandson of Jefferson; a descendant of his brother Beverly matched the Jefferson male line. | |

| Born | May 8, 1835 |

| Died | July 12, 1892 (aged 57) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Soldier, Hotelier, Cotton Broker, Journalist |

| Parent(s) | Eston Hemings Jefferson, Julia Ann Isaacs |

| Relatives | Sally Hemings, Frederick Madison Roberts, Martha Jefferson, Thomas Jefferson, John Wayles |

Because the Y-chromosome is transferred virtually unchanged to direct male descendants, it can be studied to trace paternal genetic ancestry. In 1998, Dr. Eugene Foster led a team of scientists who collected and coded the DNA of the surviving male relatives of Jefferson's paternal uncle, Field Jefferson (as Thomas had no surviving direct male descendants by his wife), and John Carr (father of Peter and Samuel), the father of the two men Jefferson grandchildren claimed fathered Sally Heming's children. They compared their Y-chromosomes to male descendants of Eston Hemings and Thomas Woodson, whose families had long claimed Thomas Jefferson as the father through Sally Hemings. The coded DNA samples were analyzed at three universities in England.[34] [69]

The team found a match between the Hemings descendant and the Jefferson male line, who have a relatively rare Y-chromosome. There was no match to the Carr line. The team said, based on historic evidence as well,

"the simplest and most probable explanations for our molecular findings are that Thomas Jefferson, rather than one of the Carr brothers, was the father of Eston Hemings Jefferson."

Foster's team noted that numerous other male Jeffersons lived in Virginia at the time, but they said,

"a male-line descendant of Field Jefferson could possibly have illegitimately fathered an ancestor of the presumed male-line descendant of Eston. But in the absence of historical evidence to support such possibilities, we consider them to be unlikely."[34]

In addition, the study found that the Jefferson line was not related to Thomas Woodson's descendants. The Woodson descendants were found to have some European paternal ancestry.[34]

Responses

[edit]The historian Joseph Ellis, who was interviewed on the Newshour program discussing the DNA findings in November 1998, said that he had revised his opinion due to this new evidence:

- ...[T]his is really new evidence. And it—prior to this evidence, I think it was a very difficult case to know and circumstantial on both sides, and, in part, because I got it wrong, I think I want to step forward and say this new evidence constitutes, well, evidence beyond any reasonable doubt that Jefferson had a longstanding sexual relationship with Sally Hemings.[70]

The study got wide attention, with historians and commentators exploring the meaning of the complex story. Frontline featured Jefferson's Blood about the president's entire family, the implications and different points of view by many historians. Jan Ellen Lewis wrote about the effects of the Jefferson grandchildren's assertion of Carr paternity, which had been disproved:

And so the lie begun in the family becomes part of the national lie of race, which is itself a kind of truth, a fiction that orders the national life much as the moral impossibility of Jefferson's interracial liaison ordered that of his white kin.

How are we to reckon the costs entailed upon the Hemings family first by their father's silence and then by his white family's lies? Perhaps we just add them to the unpaid bill of race, the interest skill compounding, year after year, day after day.

And how are we to reckon the costs to the nation of an evasion compounded and elaborated until it became a thing in itself, a cornerstone of our civic culture?[71]

In Jefferson's Secrets: Death and Desire at Monticello (2005), the biographer Andrew Burstein, previously a skeptic, provided evidence of contemporary medical thinking in that period that justified relationships such as Jefferson's with Hemings. "The prevailing medical theory specifically gave permission to men of letters, upper class men, to find suitable sex partners to safeguard their physical and emotional health." Burstein said that he believed Jefferson had a sexual relationship with an enslaved Hemings.[37]

Thomas Jefferson Foundation

[edit]The TJF of Monticello called a Research Committee to evaluate the controversy. In 2000 its report concluded, "The DNA study, combined with multiple strands of currently available documentary and statistical evidence, indicates a high probability that Thomas Jefferson fathered Eston Hemings, and that he most likely was the father of all six of Sally Hemings's children appearing in Jefferson's records. Those children are Harriet, who died in infancy; Beverly; an unnamed daughter who died in infancy; Harriet; Madison; and Eston." It found no written evidence that the relationship began in Paris nor that Sally bore a child upon their return in 1790.[72]

The report cited Fraser Neiman's analysis of probability published in the William & Mary Quarterly. Dr. Neiman is head of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation's Archaeology Department. He analyzed the timing of Jefferson's visits to Monticello and Hemings's pregnancies, and concluded that it was highly likely that the two series of events were related. The committee noted that "Randolph Jefferson and his sons are not known to have been at Monticello at the time of Eston Hemings’s conception." Further, they noted that although it was possible that two of Randolph's sons could have visited during the conception period of Harriet and Madison, "convincing evidence does not exist for the hypothesis that another male Jefferson was the father of Sally Hemings’s children."

- Dissenting: Ken White Wallenborn said there was no "definitive answer as to Thomas Jefferson's paternity of Sally Hemings' son Eston Hemings or for that matter the other four of her children."[73] Not originally published with the Committee's report, his dissent has been added.

Responses

[edit]- A special issue of The William and Mary Quarterly also reviewed the evidence and concluded that Jefferson likely had the long-term affair and children with Sally Hemings.[74] One article told of the findings of a probability analysis related to Hemings' conception dates and Jefferson's residencies at Monticello. As noted before in this article, she only conceived when he was there. The study concluded there was a 99 percent chance that Jefferson fathered all her children.[75]

- David Mayer, a lawyer and historian, said that committee members were biased, or had a conflict of interest because of concurrent work on an oral history project at Monticello, Getting Word, being conducted among descendants of slave families. He noted that the Committee did not accept the Woodson family's oral history as sufficient for its claim of descent from Jefferson and Hemings. He thought the Committee did not weigh all oral history assertions fairly; specifically, he thought the committee gave more weight to Israel Jefferson, the slave who corroborated Madison Hemings' account, than to Monticello overseer Edmund Bacon, who said that Jefferson did not father Harriet. (Note: Bacon did not come to work at Monticello until five years after Harriet was born so could not have observed any relationship at that time by her mother.) Mayer criticized Neiman's probability analysis of Hemings' conceptions in William & Mary Quarterly as flawed, saying it was based on scant evidence that all of Hemings' children had the same father.[51]

- Fact: The slave families at Monticello were documented as quite stable. As the historian Andrew Boulton noted, "all previous testimony has agreed that Sally Hemings was faithful to the one father of all her children."[9]

Scholars Commission report

[edit]In January 2000, Herbert Barger, a Jefferson family historian and one of the founders of the newly established Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society (TJHS), suggested testing the remains of William Hemings, Madison Hemings's son, to determine if he descended from a different line. Hemings family descendants declined to permit disturbing the grave, saying they would not permit such action until Jefferson's remains were tested for his DNA. Shay Banks-Young, a Hemings-Jefferson descendant, said the family was satisfied with its tradition and the existing studies.[76]

Later in 2000, the TJHS created a "Jefferson-Hemings Scholars Commission", composed of thirteen scholars representing a variety of disciplines, to examine the paternity question.[77] On April 12, 2001, they issued a report that concluded "the Jefferson-Hemings allegation is by no means proven." The majority suggested the most likely alternative was that Randolph Jefferson, Thomas's younger brother, was the father of Eston.[78] They noted 25 possible male Jeffersons lived in Virginia at the time, and eight of those lived close to or at Monticello.[51]

Dissenting from the majority opinion, study member Paul Rahe wrote that he considered

"it somewhat more likely than not that Thomas Jefferson was the father of Eston Hemings," and added "there is ... one thing that we do know, and it is damning enough. Despite the distaste he expressed for the propensity of slaveholders and their relatives to abuse their power, Jefferson either engaged in such abuse himself or tolerated it on the part of one or more members of his extended family."[79]

- Criticism of the Scholars Commission report

- The historian Alexander Boulton wrote in the William and Mary Quarterly about the report, and about a book published the same year by the TJHS, that they were amateur historical efforts:

"Past defenses of Jefferson having proven inadequate, the TJHS advocates have pieced together an alternative case that preserves the conclusions of earlier champions but introduces new "evidence" to support them. Randolph Jefferson, for example, had never seriously been considered as a possible partner of Sally Hemings until the late 20th century, when DNA evidence indicated that a Jefferson was unquestionably the father of Eston." He also noted, "The Heritage Society authors suggest that Sally had multiple partners, including Randolph

and one of the Carrs. They are undeterred by the absence of evidence for such claims; all previous testimony has agreed that Sally Hemings was faithful to the one father of all her

children."[9]

Boulton says that "a central issue [is] at the heart of the new consensus: Jefferson's contemporaries said nothing about the affair because they, like ourselves, have been in a state of denial about America's long, tangled history of interracial sex".[9]

The first person to suggest a link between Randolph Jefferson and Sally Hemings was the playwright Karyn Traut in 1988 with her play Saturday's Children, based on her own research.[80] Her husband, biologist Thomas Traut, was a member of the Scholars Commission. The report includes Appendices by each of them.[81]

- In 2003, a team of genealogical researchers, after examining primary source documents including census, tax, land, and marriage records, as well as the letters of Jefferson and his contemporaries, addressed the possibility of Randolph Jefferson's paternity or that of his sons. They concluded that Randolph Jefferson was an infrequent and reluctant visitor to Monticello. They found his sons were most likely too young to have fathered Sally's children, and that there was no evidence they were raised or educated at Monticello prior to 1813, when the last Hemings son was born.[41]

National Genealogical Society

[edit]The National Genealogical Society Quarterly of September 2001 examined the controversy from the perspectives of several professionally certified genealogists. They criticized the Scholars Commission report for failing to adhere to the standards of genealogical research, which the NGS authors characterized as more stringent than the legalistic paradigm adopted by the commission. Specifically, the genealogist Helen F. M. Leary noted that the Scholars Commission's failings included: over-reliance on derivative sources, biased assessment of data, distortion of evidence, deficient context, and, most importantly, ignoring the weight of the body of evidence.[82] Leary concluded that "the chain of evidence securely fastens Sally Hemings's children to their father, Thomas Jefferson."[83][84]

Monticello Association

[edit]A majority of the members of the private lineage society, the Monticello Association, who claim descent from Jefferson and Martha Wayles, in 1999 commissioned a scholarly study to review the evidence. After the DNA results had been publicized, they had to decide whether to admit Hemings descendants as members. After receiving the study, which concluded there was insufficient written data of the kind that fulfilled the Association's documentation requirements, most of the members voted in 2002 not to admit Hemings' descendants. They acknowledged that it could be difficult for descendants of slaves to satisfy their membership documentation requirements, but the members did not want to change their rules to acknowledge the DNA evidence. They would accept only DNA evidence directly from Jefferson, and the family descendants do not want his grave disturbed.

Woodson family

[edit]The Woodson family descendants continue to press their case in A President in the Family (2002). In this book, they argue that: (1) there was an erasure in Jefferson's farm book in the section on slaves born in 1790; (2) Thomas Jefferson's record of gifts in the years 1800 and 1801 indicated that gifts were given to a 'servant' named Thomas (Callender's "Tom" would have been 10 years old at the time of the gifts); (3) the historian Joseph Ellis's early entry into the reporting process violated the promises of Dr. Foster (the DNA test organizer), who had said that historians would not be involved with the test or the reporting. They criticized him for losing control of the process.[85]

Scholarship changes

[edit]American historians now widely believe that Jefferson had a long-term relationship with Hemings and fathered her children. Several new books have been published which include this change in accepted history, including ones by young scholars, such as Joshua D. Rothman who wrote a study of interracial relationships in Virginia, and established scholars such as Gordon Wood and Jack Rakove, whose books in the 2000s reflect the new consensus on Jefferson. In 2004, the historian Philip D. Morgan told Time magazine that he "felt stupid" for having failed to see the connection before.

In 2008, the historian Annette Gordon-Reed was the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize for history, in addition to 15 other major historical and literary awards, for The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family. In 2010 the MacArthur Foundation awarded a fellowship to the Gordon-Reed for her "persistent investigation into the life of an iconic American president [that] has dramatically changed the course of Jeffersonian scholarship."[86] Scholars remain open to more evidence. Among the public, most accepted the idea of Thomas Jefferson's and Sally Hemings's relationship, long before the historians. In 2005, Paul Finkelman and his students polled visitors to Monticello; 80 percent said they were not surprised by the DNA results showing a match between the Jefferson male line and Hemings' descendant.

New reunions and Monticello Community

[edit]In 2010 the international peace-making organization "Search for Common Ground" honored three descendants of Thomas Jefferson: Shay Banks-Young, who identifies as African American, and Julie Jefferson Westerinen, who identifies as white, both descendants of Sally Hemings; and David Works, descended from Martha Wayles, for "their work to bridge the divide within their family and heal the legacy of slavery."[3] They have been featured on NPR and in other interviews across the country, where they have talked about race and the meaning of the Jefferson-Hemings story.[3]

Shay Banks-Young said her family always talked about where they came from. She and her family became more involved at Monticello because of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation's project of the 1990s called "Getting Word", in which descendants of slave families at Monticello were interviewed for oral histories. Julie Jefferson Westerinen first found out about her full heritage after Fawn McKay Brodie's biography came out in 1974, when her family recognized Eston Hemings Jefferson's name and discussed it. They discovered that in the 1940s, her father and his brothers decided not to tell their descendants about the Jefferson-Hemings connection, for fear of racial discrimination. Her brother was the Eston Hemings descendant tested whose DNA matched the Y-chromosome of the Jefferson male line. The three have organized larger reunions at the estate and have started a new association, the "Monticello Community", "for all the descendants of workmen, artisans and slave, free, family, whatever, at Monticello."[3]

In popular culture

[edit]- Barbara Chase-Riboud wrote the novel Sally Hemings (1979), a few years after Brodie's biography was published. Given its wide success, CBS was considering a miniseries adapted from the book, but the historians Dumas Malone and Virginius Dabney (a Jefferson-Dabney descendant) contacted the network president William Paley to campaign against such a program. The project was dropped.[87]

- The Merchant-Ivory film Jefferson in Paris (1995) reached large audiences. Many Americans seemed more willing than most mainstream historians to believe that Jefferson had an intimate relationship with an attractive mixed-race slave who was half sister to his beloved late wife.

- Sally Hemings: An American Scandal (2000), a CBS miniseries, portrayed the relationship from its beginning in Paris. It was cast with numerous actors of European-African American ancestry to portray the many mixed-race slaves among the house servants at Monticello, including Hemings and her children.

- The scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr. has had two television series, African American Lives[ (2000) and African American Lives 2 (2006) examining the complex family histories of prominent African Americans, including DNA analysis of their ancestry. Geneticists assisting the show say that population studies show that 58 percent of African Americans have at least 12.5 percent European ancestry - the equivalent of one great-grandparent. A smaller but significant percentage have a higher amount of European ancestry.[88]

- Steve Erickson's avantpop novel Arc d'X (1993) begins with the historical figures of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, but shifts to another world after he is elected president.

References

[edit]- ^ a b François Furstenberg, "Jefferson's Other Family: His concubine was also his wife's half-sister", Slate, 23 September 2008, accessed 11 March 2011

- ^ Joseph Ellis, American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson, New York: 1993

- ^ a b c d e f g Michel Martin, "Thomas Jefferson Descendants Work To Heal Family's Past", NPR, 11 November 2010, accessed 2 March 2011 Cite error: The named reference "Martin" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Judge Sibley, "Beautiful Octoroon: Miss Anna Heming", originally in Scioto Gazette, 7 Aug 1902; Jefferson's Blood, PBS Frontline, 2002, accessed 25 March 2011

- ^ Andrew O. Boulton, "The Monticello Mystery Case Continued", William and Mary Quarterly, Volume LVIII, No. 4, 2001, accessed 13 August 2011

- ^ "John Wayles", Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, Monticello, accessed 9 March 2011

- ^ Frank W. Sweet, "The Transition Period", Backintyme Essays, accessed 21 Apr 2009

- ^ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, 1619-1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, p. 17

- ^ a b c d e f Alexander Boulton, "The Monticello Mystery-Case Continued", reviews of The Jefferson-Hemings Myth: An American Travesty; A President in the Family: Thomas Jefferson, Sally Hemings and Thomas Woodson; and Free Some Day: African American Families at Monticello; in 'William & Mary Quarterly, Third Series, Vol. 58, No. 4, October 2001, accessed 4 March 2011 Cite error: The named reference "wm" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "The Legacies of Monticello", Getting Word, Monticello, accessed 19 March 2011

- ^ Helen F. M. Leary, National Genealogical Society Quarterly, Vol. 89, No. 3, September 2001, pp. 207, 214 - 218 Quote: Leary concluded that "the chain of evidence securely fastens Sally Hemings's children to their father, Thomas Jefferson."

- ^ Gordon-Reed, Annette (1998). Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy. University of Virginia Press. Retrieved 03-04-2011.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Fawn Brodie, Thomas Jefferson, p. 287

- ^ Joshua D. Rothman

- ^ Gordon-Reed, American Controversy, pp. 80-83

- ^ The Memoirs of Madison Hemings, Thomas Jefferson: Frontline, PBS-WGBH

- ^ Gordon-Reed, Controversy, pp. 24, 81

- ^ Allison, Andrew, K. DeLynn Cook, M. Richard Maxfield, W. Cleon Skousen, The Real Thomas Jefferson, pp. 232-233, National Center for Constitutional Studies, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Gordon-Reed, American Controversy, p. 81

- ^ Gordon-Reed, American Controversy, pp. 83-84

- ^ Gordon-Reed, American Controversy, pp. 14-22

- ^ Winthrop Jordan, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550-1812, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968

- ^ a b c Fawn McKay Brodie, Thomas Jefferson, An Intimate History (1974)

- ^ Gordon-Reed, An American Controversy

- ^ Halliday (2001), Understanding Thomas Jefferson, pp. 162-167

- ^ William & Mary Quarterly

- ^ Gordon-Reed, American Controversy, pp. 210-223

- ^ Gordon-Reed, American Controversy, pp. 210-223

- ^ a b c "Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account", Monticello, accessed 4 March 2011

- ^ Gordon-Reed, American Controversy, pp. 210-223

- ^ Gordon-Reed, American Controversy, p. 34

- ^ Gordon-Reed, An American Controversy, pp. 38-43

- ^ Gordon-Reed, American Controversy, pp. 40-41, 210-223

- ^ a b c d e f g Foster, EA; Jobling, MA; Taylor, PG; Donnelly, P; De Knijff, P; Mieremet, R; Zerjal, T; Tyler-Smith, C; et al. (1998). "Jefferson fathered slave's last child" (PDF). Nature. 396 (6706): 27–28. doi:10.1038/23835. PMID 9817200.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - ^ DNA typing: biology, technology, and genetics of STR markers. John Marshall Butler, Elsevier Academic Press, 2005. pg 224-9

- ^ "Online Newshour: Thomas Jefferson". pbs.org. 1998-11-02. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

- ^ a b c Richard Shenkman, "The Unknown Jefferson: An Interview with Andrew Burstein", History News Network, 25 July 2005, accessed 14 March 2011 Cite error: The named reference "Shenkman" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Extraordinary Ancestors", Getting Word, Monticello, accessed 19 March 2011

- ^ "Conclusions", Report of the Research Committee on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, Monticello, January 2000, accessed 9 March 2011. Quote: "The DNA study, combined with multiple strands of currently available documentary and statistical evidence, indicates a high probability that Thomas Jefferson fathered Eston Hemings, and that he most likely was the father of all six of Sally Hemings's children appearing in Jefferson's records. Those children are Harriet, who died in infancy; Beverly; an unnamed daughter who died in infancy; Harriet; Madison; and Eston."

- ^ "Doubts About Jefferson and Hemings", Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society

- ^ a b Jeanette K. B. Daniels, AG, CGRS, Marietta Glauser, Diana Harvey, and Carol Hubbell Ouellette, "Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, A Look at Some Original Documents", Heritage Quest Magazine, May/June 2003

- ^ National Genealogical Society Quarterly, Vol. 89, No. 3, September 2001, pp. 214 - 218

- ^ National Genealogical Society Quarterly, Vol. 89, No. 3, September 2001, p. 207

- ^ Rebecca Gates-Coon, "The Children of Sally Hemings: Genealogist Gives Annual Austin Lecture", Information Bulletin, Library of Congress, May 2002, accessed 10 Feb 2009. Quote: Leary said: "[M]uch of the evidence marshaled against the Hemings-Jefferson relationship has proved to be flawed by reason of bias, inaccuracy or inconsistent reporting. Too many coincidences must be accounted for and too many unique circumstances "explained away" if a competing theory is to be accepted. The sum of the evidence points to Jefferson as the father of Hemings' children."

- ^ a b Chris Kahn, "Reunion bridges Jefferson family rift: Snubbed descendants of black slave hold their own event", Genealogy, MSNBC, 13 July 2003, accessed 1 March 2011

- ^ "The Monticello Community", Official Website

- ^ Miller 1977, pp. 152–153

- ^ Gordon-Reed, Annette. Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy, University of Virginia Press (April 1997), pp. 59–61. ISBN 0813916984

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

HemingsMontwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Allison, Andrew, K. DeLynn Cook, M. Richard Maxfield, W. Cleon Skousen, The Real Thomas Jefferson, pp. 232-233, National Center for Constitutional Studies, Washington, D.C.

- ^ a b c d Mayer, David (2001-04-09). "The Thomas Jefferson - Sally Hemings Myth and the Politicization of American History". Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ Jordan, Winthrop D. White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550-1812, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968

- ^ "Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account", Monticello Foundation, accessed 9 February 2011

- ^ a b Gordon-Reed, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, pp. 3, accessed 9 February 2011

- ^ "Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account", Monticello, accessed 4 March 2011

- ^ Gordon-Reed, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, pp. 19 - 22

- ^ "Waverly Watchman rebuttal"

- ^ James T. Campbell, Songs of Zion, New York: Oxford University Press, 1995, pp. 259-260, accessed 13 Jan 2009

- ^ Gordon-Reed, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, p. 22

- ^ "A sprig of Jefferson", PBS Frontline

- ^ Winthrop Jordan, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550-1812, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968

- ^ Gordon-Reed, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings

- ^ Halliday (2001), Understanding Thomas Jefferson, pp. 162-167

- ^ Gordon-Reed, Thomas Jefferson & Sally Hemings, pp. 210-223

- ^ "Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account", Plantation & Slavery, Monticello, accessed 9 March 2011

- ^ Byron Woodson, A President in the Family (2002)

- ^ Baron, Robert (ed.). The Garden and Farm Books of Thomas Jefferson. Fulcrum, 1987, p. 247

- ^ "Jefferson-Hemings Report" (PDF). Thomas Jefferson Foundation. 2001-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-13. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ DNA typing: biology, technology, and genetics of STR markers. John Marshall Butler, Elsevier Academic Press, 2005. pg 224-9

- ^ "Online Newshour: Thomas Jefferson". pbs.org. 1998-11-02. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

- ^ J.E. Lewis, "The White Jeffersons", in Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson: History, Memory and Civil Culture], ed. J.E. Lewis and P.S. Onuf, Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1999, excerpted on Frontline website, accessed 17 March 2011

- ^ "Conclusions", Report of the Research Committee on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, Monticello, January 2000, accessed 9 March 2011

- ^ Mayer, David N. (April 9, 2001). "The Thomas Jefferson - Sally Hemings Myth and the Politicization of American History". Ashbrook. Retrieved 02-14-2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Forum: Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings Redux," The William and Mary Quarterly, LVII (January 2000), 121-210

- ^ Lucia C. Stanton, "Elizabeth Hemings and Her Family", Free Some Day: The African American Families of Monticello], University of North Carolina Press, 2000, p. 117, accessed 13 August 2011

- ^ "Historian wants access to Kansas grave in probing link between Jefferson, slave", AP, 4 January 2000, in Topeka Capital Journal (CJ Online), accessed 2 December 2008

- ^ Turner, Robert F. Scholars Commission. The Wall Street Journal Opinion Journal. 4 July 2001.

- ^ "Doubts About Jefferson and Hemings", Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society

- ^ "Scholars' Commission Report", Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society

- ^ [http://books.google.com/books?id=BjtCG8vVQEEC&dq=Karyn+Traut&source=gbs_navlinks_s William G. Hyland, In Defense of Thomas Jefferson: The Sally Hemings Sex Scandal, New York, MacMillan, 2009, p. 35, accessed 11 March 2011

- ^ [http://h-net.msu.edu/cgi-bin/logbrowse.pl?trx=vx&list=h-oieahc&month=0304&week=a&msg=9FpGxNfSd5EN/P2FQKMkKQ&user=&pw= John L. Bell, "Jefferson-Hemings popular resources for course use", H-Net Discussion Network, 3 April 2003. Quote: "Prof Thomas Traut was not only a member of the Department of Biochemistry & Biophysics at UNC-Chapel Hill; he was also the spouse of Karyn Traut, author of a play portraying the father of Sally Hemings's children as Thomas Jefferson's brother Randolph.

I believe that play, produced in 1988, was the first public linking of Sally Hemings and Randolph Jefferson in fiction or non-fiction in over 180 years of discussion of the Hemings children. No one at Monticello and no one in the Hemings or Jefferson families had written of those two people together before Karyn Traut." - ^ National Genealogical Society Quarterly, Vol. 89, No. 3, September 2001, pp. 214 - 218

- ^ National Genealogical Society Quarterly, Vol. 89, No. 3, September 2001, p. 207

- ^ Rebecca Gates-Coon, "The Children of Sally Hemings: Genealogist Gives Annual Austin Lecture", Information Bulletin, Library of Congress, May 2002, accessed 10 Feb 2009. Quote:Leary said: "[M]uch of the evidence marshaled against the Hemings-Jefferson relationship has proved to be flawed by reason of bias, inaccuracy or inconsistent reporting. Too many coincidences must be accounted for and too many unique circumstances "explained away" if a competing theory is to be accepted. The sum of the evidence points to Jefferson as the father of Hemings' children."

- ^ Woodson, Byron. A President in The Family. Praeger, 2001. pp. 217, 246, 222-229.

- ^ "Annette Gordon-Reed", MacArthur Foundation, accessed 9 February 2011

- ^ Gordon-Reed, American Controversy, p. 183

- ^ Henry Louis Gates, Jr., In Search of Our Roots: How 19 Extraordinary African Americans Reclaimed Their Past, New York: Crown Publishing, 2009, pp. 20-21

- Miller, John Chester,The Wolf by the Ears, New York: The Free Press, 1977

Further reading

[edit]- Mary Boykin Chesnut, A Civil War Diary (1905, new revised editions: 1949, 1981)

- Fanny Kemble, Journal of a Residence on a Georgia Plantation in 1838-1839 (1863)

- Eugene Genovese, Roll, Jordan Roll

- Annette Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family (2008)

- Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, 1619-1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993

- Nell Irvin Painter, Southern History Across the Color Line, University of North Carolina Press, 2002

- Joshua D. Rothman, Notorious in the Neighborhood: Sex and Families across the Color Line in Virginia, 1787-1861, University of North Carolina Press, 2003

External links

[edit]- Thomas Jefferson Foundation/Monticello