Meuse–Argonne offensive

| Meuse-Argonne Offensive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of World War I | |||||||

Dugouts in the Argonnes (1918) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

380 tanks 840 planes 2,780 artillery pieces | 450,000 personnel | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Total: 192,000[3] 26,277 killed 95,786 wounded |

Total: c. 126,000[4] 28,000 dead 42,000 wounded 26,000 POWs taken by Americans 30,000 POWs taken by French 874 artillery pieces captured by both[5] | ||||||

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive, also known as the Maas-Argonne Offensive and the Battle of the Argonne Forest, was a major part of the final Allied offensive of World War I that stretched along the entire Western Front. It was fought from 26 September 1918 until the Armistice of 11 November 1918, a total of 47 days. The Meuse-Argonne Offensive was the largest in United States military history, involving 1.2 million American soldiers. It was one of a series of Allied attacks known as the Hundred Days Offensive, which brought the war to an end. The battle cost 28,000 German lives, 26,277 American lives and an unknown number of French lives. It was the largest and bloodiest operation of World War I for the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), which was commanded by General John J. Pershing, and the second-deadliest battle in American history. American losses were exacerbated by the inexperience of many of the troops, and tactics used during the early phases of the operation.

The Meuse-Argonne was the principal engagement of the AEF during World War I.

Overview

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2016) |

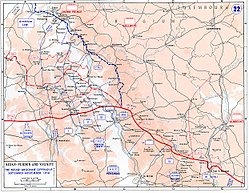

The logistical prelude to the Meuse attack was planned by then-Colonel George Marshall who managed to move American units to the front after the Battle of Saint-Mihiel. The big September/October Allied breakthroughs (north, centre and south) across the length of the Hindenburg Line – including the Battle of the Argonne Forest – are now lumped together as part of what is generally remembered as the Grand Offensive (also known as the Hundred Days Offensive) by the Allies on the Western Front. The Meuse-Argonne offensive also involved troops from France, while the rest of the Allies, including France, Britain and its dominion and imperial armies (mainly Canada, Australia and New Zealand), and Belgium contributed to major battles in other sectors across the whole front.

The French and British armies' ability to fight unbroken over the whole four years of the war, in what amounted to a bloody stalemate, is credited by some historians with breaking the spirit of the German Army on the Western Front. The Grand Offensive, including British, French and Belgian advances in the north along with the French-American advances around the Argonne forest, is in turn credited for leading directly to the Armistice of 11 November 1918.

On 26 September, the Americans began their strike north towards Sedan. The next day British and Belgian divisions drove towards Ghent (Belgium). British and French armies attacked across northern France on 28 September. The scale of the overall offensive, bolstered by the fresh and eager, but largely untried and inexperienced, U.S. troops, signaled renewed vigor among the Allies and sharply dimmed German hopes for victory.

The Meuse-Argonne offensive, shared by the U.S. forces with the French Fourth Army on the left, was the biggest operation and victory of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) in World War I. The bulk of the AEF had not gone into action until 1918. The Meuse-Argonne battle was the largest frontline commitment of troops by the U.S. Army in World War I, and also its deadliest. Command was coordinated, with some U.S. troops (e.g. the Buffalo Soldiers of the 92nd Division and the 93rd Division) attached and serving under French command (e.g. XVII Corps during the second phase).

The main U.S. effort of the Meuse-Argonne offensive took place in the Verdun Sector, immediately north and northwest of the town of Verdun, between 26 September and 11 November 1918. However, far to the north, U.S. troops of the 27th and 30th divisions of the II Corps AEF fought under British command in a spearhead attack on the Hindenburg Line with 12 British and Australian divisions, and directly alongside the exhausted veteran divisions of the Australian Corps of the First Australian Imperial Force (1st AIF).[7] With artillery and British tanks, the combined three-nation force, despite some early setbacks, attacked and captured their objectives (including Montbrehain village) along a six-kilometre section of the Line between Bellicourt and Vendhuille, which was centred around an underground section of the St. Quentin Canal and came to be known as the Battle of St. Quentin Canal. Although the capture of the heights above the Beaurevoir Line by 10 October, marking a complete breach in the Hindenburg Line, was arguably of greater immediate significance,[8] the important U.S. contribution to the victory at the St. Quentin Canal is less well remembered in the United States than Meuse-Argonne.

Prelude

Opposing forces (Reims to Argonne)

The American forces initially consisted of fifteen divisions of the U.S. First Army commanded by then-General John J. Pershing until 16 October, and then by Lieutenant General Hunter Liggett.[9] The logistics were planned and directed by then-Colonel George C. Marshall. The French forces next to them consisted of 31 divisions including the Fourth Army (under Henri Gouraud) and the Fifth Army (under Henri Mathias Berthelot).[10] The U.S. divisions of the AEF were oversized (12 battalions per division versus the French/British/German 9 battalions per division), being up to twice the size of other Allies' battle-depleted divisions upon arrival, but the French and other Allied divisions had been partly replenished prior to the Grand Offensive, so both the U.S. and French contributions in troops were considerable. Most of the heavy equipment (tanks, artillery, aircraft) was provided by the European Allies. For the Meuse-Argonne front alone, this represented 2,780 artillery pieces, 380 tanks and 840 planes. As the battle progressed, both the Americans and the French brought in reinforcements. Eventually, 22 American divisions would participate in the battle at one time or another, representing two full field armies.[11] Other French forces involved included the 2nd Colonial Corps, under Henri Claudel, which had also fought alongside the AEF at the Battle of Saint-Mihiel earlier in September 1918.

The opposing forces were wholly German. During this period of the war, German divisions procured only 50 percent or less of their initial strength. The 117th Division, which opposed the U.S. 79th Division during the offensive's first phase, had only 3,300 men in its ranks. Morale varied among German units. For example, divisions that served on the Eastern front would have high morale, while conversely divisions that had been on the Western front had poor morale. Resistance grew to approximately 200,000–450,000 German troops from the Fifth Army of Group Gallwitz commanded by General Georg von der Marwitz. The Americans estimated that they opposed parts of 44 German divisions overall, though many fewer at any one time.

Objective

The Allied objective was the capture of the railway hub at Sedan that would break the railway network supporting the German Army in France and Flanders.

Battle

First phase: 26 September to 3 October

"During the three hours preceding H hour, the Allies expended more ammunition than both sides managed to fire throughout the four years of the [American] Civil War. The cost was later calculated to have been $180 million, or $1 million per minute."[12] The American attack began at 05:30 on 26 September with mixed results. The V and III Corps met most of their objectives, but the 79th Division failed to capture Montfaucon, the 28th "Keystone" Division was virtually ground to a halt by formidable German resistance, and the 91st "Wild West" Division was compelled to evacuate the village of Épinonville though it advanced 8 km (5.0 mi). The inexperienced 37th "Buckeye" Division failed to capture Montfaucon d'Argonne. The subsequent day, 27 September most of 1st Army failed to make any gains. The 79th Division finally captured Montfaucon and the 35th "Santa Fe" Division captured the village of Baulny, Hill 218, and Charpentry, placing the division forward of adjacent units. On 29 September, six extra German divisions were deployed to oppose the American attack, with the 5th Guards and 52nd Division counterattacking the 35th Division, which had run out of food and ammunition during the attack. The Germans initially made significant gains, but were barely repulsed by the 35th Division's 110th Engineers, 128th Machine Gun Battalion, and Harry Truman's Battery D, 129th Field Artillery. In the words of Pershing, "We were no longer engaged in a maneuver for the pinching out of a salient, but were necessarily committed, generally speaking, to a direct frontal attack against strong, hostile positions fully manned by a determined enemy."[13] The German counterattack had shattered so much of the 35th Division—a poorly led division, most of whose key leaders had been replaced shortly before the attack, made up of National Guard units from Missouri and Kansas—that it had to be relieved early, though remnants of the division subsequently reentered the battle.[14][15] Part of the adjacent French attack met temporary confusion when one of its generals died. However, it was able to advance 15 km (9 mi), penetrating deeply into the German lines, especially around Somme-Py (the Battle of Somme-Py (French: Bataille de Somme-Py)) and northwest of Reims (the Battle of Saint-Thierry (French: Bataille de Saint-Thierry)).[10] The initial progress of the French forces was thus faster than the 3 to 8 km (2 to 5 mi) gained by the adjacent American units, though the French units were fighting in a more open terrain, which is an easier terrain from which to attack.[3]

Second phase: 4 October to 28 October

The second phase of the battle began on 4 October, during which time all of the original phase one assault divisions (the 91st, 79th, 37th and 35th) of the U.S. V Corps were replaced by the 32nd, 3rd and 1st Divisions. The 1st Division created a gap in the lines when it advanced 2.5 km (1.6 mi) against the 37th, 52nd, and 5th Guards Divisions. It was during this phase that the Lost Battalion affair occurred. The battalion was rescued due to an attack by the 28th and 82nd Divisions (the 82nd attacking soon after taking up its positions in the gap between the 28th and 1st Divisions) on 7 October. The Americans launched a series of costly frontal assaults that finally broke through the main German defenses (the Kriemhilde Stellung of the Hindenburg Line) between 14–17 October (the Battle of Montfaucon (French: Bataille de Montfaucon)). By the end of October, US troops had advanced ten miles and had finally cleared the Argonne Forest. On their left the French had advanced twenty miles, reaching the Aisne River.[3] It was during the opening of this operation, on 8 October, that Corporal (later Sergeant) Alvin York made his famous capture of 132 German prisoners near Cornay.[16]

-

328th Infantry Regiment of 82nd Infantry Division line of advance in capture of Hill 223 on October 7, 1918.

-

Stereoscope of the ruins of the Battle of Montfaucon

Third phase: 28 October to 11 November

By 31 October, the Americans had advanced 15 km (9.3 mi) and had finally cleared the Argonne Forest. On their left the French had advanced 30 km (19 mi), reaching the River Aisne. The American forces reorganized into two armies. The First, led by General Liggett, would continue to move to the Carignan-Sedan-Mezieres Railroad. The Second Army, led by Lieutenant General Robert L. Bullard, was directed to move eastward towards Metz. The two U.S. armies faced portions of 31 German divisions during this phase. The American troops captured German defenses at Buzancy, allowing French troops to cross the River Aisne, whence they rushed forward, capturing Le Chesne (the Battle of Chesne (French: Bataille du Chesne)).[17] In the final days, the French forces conquered the immediate objective, Sedan and its critical railroad hub (the Advance to the Meuse (French: Poussée vers la Meuse)), on 6 November and American forces captured surrounding hills. On 11 November, news of the German armistice put a sudden end to the fighting.

Notes

- ^ a b c d Hart, Keith (1982). "A Note on the Military Participation of Siam in the First World War" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. p. 135. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ Ferrell, Robert H. 2012. America's Deadliest Battle: Meuse-Argonne, 1918. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

- ^ a b c "Meuse River-Argonne Forest Offensive, 26 September-11 November 1918". Historyofwar.org. Retrieved 2013-09-26.

- ^ "Collier's New Encyclopedia: A Loose-leaf and Self-revising Reference Work". 1922. Page 209.

- ^ Gary Mead: Doughboys

- ^ "Red Hand Flag | History Detectives". PBS. 2011-05-15. Retrieved 2013-09-26.

- ^ "Hindenburg Line and Montbrehain, 27 September – 5 October 1918". Australians on the Western Front 1914–1918: An Australian journey across the First World War battlefields of France and Belgium. Department of Veteran's Affairs, Australian Government. November 2008.

- ^ "30th-Division in WWI". Battlefield Tour Guide.

- ^ "firstworldwar.com". Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ^ a b "Situation au debut D'Octobre 1918 (Situation at the beginning of October 1918)". Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ^

"Battle of Argonne Began 18 Years Ago". New York Times. Associated Press. 1937-09-27. Retrieved 2013-09-26.

"Battle of Argonne Began 18 Years Ago". New York Times. Associated Press. 1937-09-27. Retrieved 2013-09-26. Eighteen years ago today at dawn the American First Army started its pivotal attack which smashed the Hindenburg line on the western front and forced the imperial German command to sue for armistice.

(subscription required) - ^ D'Este, Carlo (1995). Patton: A Genius for War. New York: Harper Collins. p. 254. ISBN 0060164557.

- ^ "The Meuse-Argonne Offensive: Part II: Pershing's Report". The Great War Society. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ^ Ferrell, Robert H. (2004). Collapse at Meuse-Argonne: The Failure of the Missouri-Kansas Division. University of Missouri Press. p. 176. ISBN 0-8262-1532-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "35th Infantry Division (Mechanized) 'The Santa Fe Division'". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ Fleming, Thomas (October 1993). "Meuse-Argonne Offensive of World War I". Military History. HistoryNet.com.

- ^ "Novembre 1918 (November 1918)". Retrieved 2009-10-08.

References

- Baker, Horace L. (2007). Argonne Days in World War I. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-82626-575-8. OCLC 614477736.

- Braim, Paul (1987). The Test of Battle: the American Expeditionary Forces in the Meuse-Argonne Campaign. Newark: University of Delaware Press. ISBN 0-87413-301-7. OCLC 14240589.

- Clodfelter, Michael (2007). The Lost Battalion and the Meuse-Argonne, 1918: America's Deadliest Battle. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 0786426799. OCLC 71812758.

- Ferrell, Robert H. (2007). America's Deadliest Battle: The Meuse Argonne, 1918. Lawrence: University press of Kansas. ISBN 0-70061-499-0. OCLC 71275542.

- Ferrell, Robert H. (2004). Collapse at Meuse-Argonne: the Failure of the Missouri-Kansas Division. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-82621-532-7. OCLC 54500285.

- Lengel, Edward G. (2008). To Conquer Hell. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-7931-9.

- Lengel, Edward G., ed. A Companion to the Meuse-Argonne Campaign (Wiley-Blackwell, 2014). xii, 537 pp.

- Palmer, Fredrick (1919). Our Greatest Battle: The Meuse Argonne. New York: Dodd, Meade.

- Wright, William M. (2004). Ferrell, Robert H. (ed.). Meuse-Argonne Diary: A Division Commander in World War I. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0826215277. OCLC 70757341.

- Yockelson, Mitchell. Forty-Seven Days: How Pershing's Warriors Came of Age to Defeat at the German Army in World War I (New York: NAL, Caliber, 2016) ISBN 978-0-451-46695-2