Burke and Hare murders

The Burke and Hare murders were a series of 16 killings committed over a period of about ten months in 1828 in Edinburgh, Scotland. They were undertaken by William Burke and William Hare, who sold the corpses to Robert Knox for dissection at his anatomy lectures.

Edinburgh was a leading European centre of anatomical study in the early 19th century, in a time when the demand for cadavers led to a shortfall in legal supply. Scottish law required that corpses used for medical research should only come from those who had died in prison, suicide victims, or from foundlings and orphans. The shortage of corpses led to an increase in body snatching by what were known as "resurrection men". Measures to ensure graves were left undisturbed exacerbated the shortage. When a lodger in Hare's house died, Hare turned to his friend Burke for advice and they decided to sell the body to Knox. They received what was, for them, the generous sum of £7 10s. A little over two months later, when Hare was concerned that a lodger suffering from fever would deter others from staying in the house, he and Burke murdered her and sold the body to Knox. The men continued their murder spree, probably with the knowledge of their wives. Burke and Hare's actions were uncovered after other lodgers discovered their last victim, Margaret Docherty, and contacted the police.

A forensic examination of Docherty's body indicated she had probably been suffocated, but this could not be proven. Although the police suspected Burke and Hare of other murders, there was no evidence on which they could take action. An offer was put to Hare granting immunity from prosecution if he turned king's evidence. He provided the details of Docherty's murder and confessed to all 16 deaths; formal charges were made against Burke and his wife for three murders. At the subsequent trial Burke was found guilty of one murder and sentenced to death. The case against his wife was found not proven—a Scottish legal verdict to acquit an individual but not declare them innocent. Burke was hanged shortly afterwards; his corpse was dissected and his skeleton displayed at the Anatomical Museum of Edinburgh Medical School where, as at 2018, it remains.

The murders raised public awareness of the need for bodies for medical research and contributed to the passing of the Anatomy Act 1832. The events have made appearances in literature, and been portrayed on screen, either in heavily fictionalised accounts or as the inspiration for fictional works.

Background

Anatomy in 19th-century Edinburgh

In the early 19th century Edinburgh had several pioneering anatomy teachers, including Alexander Monro, his son who was also called Alexander, John Bell, John Goodsir and Robert Knox, all of whom developed the subject into a modern science.[1] Because of their efforts, Edinburgh became one of the leading European centres of anatomical study, alongside Leiden in the Netherlands and the Italian city of Padua.[2] The teaching of anatomy—crucial in the study of surgery—required a sufficient supply of cadavers, the demand for which increased as the science developed.[3] Scottish law determined that suitable corpses on which to undertake the dissections were those who died in prison, suicide victims, and the bodies of foundlings and orphans.[4] With the rise in prestige and popularity of medical training in Edinburgh, the legal supply of corpses failed to keep pace with the demand; students, lecturers and grave robbers—also known as resurrection men—began an illicit trade in exhumed cadavers.[5][6]

The situation was confused by the legal position. Disturbing a grave was a criminal offence, as was the taking of property from the deceased. Stealing the body was not an offence, as it did not legally belong to anyone.[7][8] The price per corpse changed depending on the season. It was £8 during the summer, when the warmer temperatures brought on quicker decomposition, and £10 in the winter months, when the demand by anatomists was greater, because the colder temperatures meant they could store corpses longer so they undertook more dissections.[9]

By the 1820s the residents of Edinburgh had taken to the streets to protest at the increase in grave robbing.[10] To avoid corpses being disinterred, bereaved families used several techniques in order to deter the thieves: guards were hired to watch the graves, and watchtowers were built in several cemeteries; some families hired a large stone slab that could be placed over a grave for a short period—until the body had begun to decay past the point of being useful for an anatomist. Other families used a mortsafe, an iron cage that surrounded the coffin.[11] The high levels of vigilance from the public, and the techniques used to deter the grave robbers, led to what the historian Ruth Richardson describes as "a growing atmosphere of crisis" among anatomists because of the shortage of corpses.[12] The historian Tim Marshall considers the situation meant "Burke and Hare took graverobbing to its logical conclusion: instead of digging up the dead, they accepted lucrative incentives to destroy the living".[13]

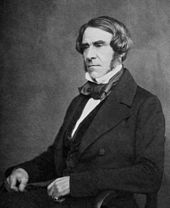

Dr Robert Knox

Knox was an anatomist who had qualified as a doctor in 1814. After contracting smallpox as a child, he was blind in one eye and badly disfigured.[14] He undertook service as an army physician at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, followed by a posting in England and then, during the Cape Frontier War (1819), in southern Africa. He eventually settled in his home town of Edinburgh in 1820. In 1825 he became a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, where he lectured on anatomy. He undertook dissections twice a day, and his advertising promised "a full demonstration on fresh anatomical subjects" as part of every course of lectures he delivered;[15] he stated that his lessons drew over 400 pupils.[16] Clare Taylor, his biographer in the Dictionary of National Biography, observes that he "built up a formidable reputation as a teacher and lecturer and almost single-handedly raised the profile of the study of anatomy in Britain".[14] Another biographer, Isobel Rae, considers that without Knox, the study of anatomy in Britain "might not have progressed as it did".[17]

William Burke and William Hare

William Burke was born in 1792 in Urney, County Tyrone, Ireland, one of two sons to middle-class parents.[18] Burke, along with his brother, Constantine, had a comfortable upbringing, and both joined the army as teenagers. Burke served in the Donegal militia until he met and married a woman from County Mayo, where they later settled. The marriage was short-lived; in 1818, after an argument with his father-in-law over land ownership, Burke deserted his wife and family. He moved to Scotland and became a labourer, working on the Union Canal.[19] He settled in the small village of Maddiston near Falkirk, and set up home with Helen McDougal, whom he affectionately nicknamed Nelly; she became his second wife.[20] After a few years, and when the works on the canal were finished, the couple moved to Tanners Close, Edinburgh, in November 1827.[21] They became hawkers, selling second-hand clothes to impoverished locals. Burke then became a cobbler, a trade in which he experienced some success, earning upwards of £1 a week. He became known locally as an industrious and good-humoured man who often entertained his clients by singing and dancing to them on their doorsteps while plying his trade. Although raised as a Roman Catholic, Burke became a regular worshipper at Presbyterian religious meetings held in the Grassmarket; he was seldom seen without a bible.[20]

William Hare was probably born in County Armagh, County Londonderry or in Newry. His age and year of birth are unknown; when arrested in 1828 he gave his age as 21, but one source states that he was born between 1792 and 1804.[18][22] Information on his earlier life is scant, although it is possible that he worked in Ireland as an agricultural labourer before travelling to Britain. He worked on the Union Canal for seven years before moving to Edinburgh in the mid-1820s, where he worked as a coal man's assistant.[18][22] He lodged at Tanner's Close, in the house of a man named Logue and his wife, Margaret Laird, in the nearby West Port area of the town. When Logue died in 1826, Hare may have married Margaret.[a] Based on contemporary accounts, Brian Bailey in his history of the murders describes Hare as "illiterate and uncouth—a lean, quarrelsome, violent and amoral character with the scars from old wounds about his head and brow".[2] Bailey describes Margaret, who was also an Irish immigrant, as a "hard-featured and debauched virago".[23]

In 1827 Burke and McDougal went to Penicuik in Midlothian to work on the harvest, where they met Hare. The men became friends; when Burke and McDougal returned to Edinburgh, they moved into Hare's Tanner's Close lodging house, where the two couples soon acquired a reputation for hard drinking and boisterous behaviour.[18]

Events of November 1827 to November 1828

On 29 November 1827 one Donald, a lodger in Hare's house, died of dropsy shortly before receiving a quarterly army pension while owing £4 of back rent.[24] After Hare bemoaned his financial loss to Burke, the pair decided to sell Donald's body to one of the local anatomists. A carpenter provided a coffin for a burial which was to be paid for by the local parish. After he left, the pair opened the coffin, removed the body—which they hid under the bed—filled the coffin with bark from a local tanners and resealed it.[25] After dark, on the day the coffin was removed for burial, they took the corpse to Edinburgh University, where they looked for a purchaser. According to Burke's later testimony, they asked for directions to Professor Monro, but a student sent them to Knox's premises in Surgeon's Square.[26][b] Although the men dealt with juniors when discussing the possibility of selling the body, it was Knox who arrived to fix the price at £7 10s.[c] Hare received £4 5s while Burke took the balance of £3 5s; Hare's larger share was to cover his loss from Donald's unpaid rent.[29] According to Burke's official confession, as he and Hare left the university, one of Knox's assistants told them that the anatomists "would be glad to see them again when they had another to dispose of".[30]

There is no agreement as to the order in which the murders took place.[31] Burke made two confessions but gave different sequences for the murders in each statement. The first was an official one, given on 3 January 1829 to the sheriff-substitute, the procurator fiscal and the assistant sheriff-clerk. The second was in the form of an interview with the Edinburgh Courant that was published on 7 February 1829.[32] These in turn differed from the order given in Hare's statement, although the pair were agreed on many of the points of the murders.[33][d] Contemporary reports also differ from the confessions of the two men. More recent sources, including the accounts written by Brian Bailey, Lisa Rosner and Owen Dudley Edwards, either follow one of the historic versions or present their own order of events.[e]

Most of the sources agree that the first murder in January or February 1828 was either that of a miller named Joseph lodging in Hare's house, or Abigail Simpson, a salt seller.[33] The historian Lisa Rosner considers Joseph the more likely; a pillow was used to smother the victim, while later ones were suffocated by a hand over the nose and mouth.[36][f] The novelist Sir Walter Scott, who took a keen interest in the case, also thought the miller was the more likely first victim, and highlighted that "there was an additional motive to reconcile them to the deed",[33] as Joseph was suffering from a fever and had become delirious. Hare and his wife were concerned that having a potentially infectious lodger would be bad for business. Hare again turned to Burke and, after providing their victim with whisky, Hare suffocated Joseph while Burke lay across the upper torso to restrict movement.[38] They again took the corpse to Knox, who this time paid £10.[39][g] Rosner considers the method of murder to be ingenious: Burke's weight on the victim stifled movement—and thus the ability to make noise—while it also prevented the chest from expanding should any air get past Hare's suffocating grip. In Rosner's opinion, the method would have been "practically undetectable until the era of modern forensics".[37]

The order of the two victims next after Joseph is also unclear; Rosner puts the sequence as Abigail Simpson followed by an English male lodger from Cheshire,[40] while Bailey and Dudley Edwards each have the order as the English male lodger followed by Simpson.[41][42] The unnamed Englishman was a travelling seller of matches and tinder who fell ill with jaundice at Hare's lodging house. As with Joseph, Hare was concerned with the effect this illness might have on his business, and he and Burke employed the same modus operandi they had with the miller: Hare suffocating their victim while Burke lay over the body to stop movement and noise.[43] Simpson was a pensioner who lived in the nearby village of Gilmerton and visited Edinburgh to supplement her pension by selling salt. On 12 February 1828—the only exact date Burke quoted in his confession—she was invited into the Hares' house and plied with enough alcohol to ensure she was too drunk to return home. After murdering her, Burke and Hare placed the body in a tea-chest and sold it to Knox.[44] They received £10 for each body, and Burke's confession records of Simpson's body that "Dr Knox approved of its being so fresh ... but [he] did not ask any questions".[45] In either February or March that year an old woman was invited into the house by Margaret Hare. She gave her enough whisky to fall asleep, and when Hare returned that afternoon, he covered the sleeping woman's mouth and nose with the bed tick (a stiff mattress cover) and left her. She was dead by nightfall and Burke joined his companion to transport the corpse to Knox, who paid another £10.[46]

Burke met two women in early April: Mary Paterson (also known as Mary Mitchell) and Janet Brown, in the Canongate area of Edinburgh.[h] He bought the two women alcohol before inviting them back to his lodging for breakfast. The three left the tavern with two bottles of whisky and went instead to his brother's house. After his brother left for work, Burke and the women finished the whisky and Paterson fell asleep at the table; Burke and Brown continued talking but were interrupted by McDougal, who accused them of having an affair. A row broke out between Burke and McDougal—during which he threw a glass at her, cutting her over the eye—Brown stated that she did not know Burke was married and left; McDougal also left, and went to fetch Hare and his wife. They arrived shortly afterwards and the two men locked their wives out of the room, then murdered Paterson in her sleep.[48] That afternoon the pair took the body to Knox in a tea-chest, while McDougal kept Paterson's skirt and petticoats; they were paid £8 for the corpse, which was still warm when they delivered it. Fergusson—one of Knox's assistants—asked where they had obtained the body, as he thought he recognised her. Burke explained that the girl had drunk herself to death, and they had purchased it "from an old woman in the Canongate". Knox was delighted with the corpse, and stored it in whisky for three months before dissecting it.[49][50] When Brown later searched for her friend, she was told that she had left for Glasgow with a travelling salesman.[49]

At some point in early-to-mid 1828 a Mrs Haldane, whom Burke described as "a stout old woman", lodged at Hare's premises. After she became drunk, she fell asleep in the stable; she was smothered and sold to Knox.[51] Several months later Haldane's daughter (either called Margaret or Peggy) also lodged at Hare's house. She and Burke drank together heavily and he killed her, without Hare's assistance; her body was put into a tea-chest and taken to Knox where Burke was paid £8.[52] The next murder occurred in May 1828, when an old woman joined the house as a lodger. One evening while she was intoxicated, Burke smothered her—Hare was not present in the house at the time; her body was sold to Knox for £10.[53] Then came the murder of Effy (sometimes spelt Effie), a "cinder gatherer" who scavenged through bins and rubbish tips to sell her findings. Effy was known to Burke, and had previously sold him scraps of leather for his cobbling business. Burke tempted her into the stable with whisky, and when she was drunk enough he and Hare killed her; Knox gave £10 for the body.[54][55] Another victim was found by Burke too drunk to stand. She was being helped by a local constable back to her lodgings when Burke offered to take her there himself; the policeman obliged, and Burke took her back to Hare's house where she was killed. Her corpse raised a further £10 from Knox.[54]

Burke and Hare murdered two lodgers in June, "an old woman and a dumb boy, her grandson", as Burke later recalled in his confession.[56] While the boy sat by the fire in the kitchen, his grandmother was murdered in the bedroom by the usual method. Burke and Hare then picked up the boy and carried him to the same room where he was also killed.[55][i] Burke later said that this was the murder that disturbed him the most, as he was haunted by his recollection of the boy's expression.[58] The tea-chest that was usually used by the couple to transport the bodies was found to be too small, so the bodies were forced into a herring barrel and taken to Surgeons' Square, where they fetched £8 each.[59][60] According to Burke's confession, the barrel was loaded onto a cart which Hare's horse refused to pull further than the Grassmarket. Hare called a porter with a handcart to help him transport the container. Once back in Tanner's Close, Hare took his anger out on the horse by shooting it dead in the yard.[61]

On 24 June Burke and McDougal departed for Falkirk to visit the latter's father. Burke knew that Hare was short of cash and had even pawned some of his clothes. When the couple returned, they found that Hare was wearing new clothes and had surplus money. After he was asked, Hare denied that he had sold another body. Burke checked with Knox, who confirmed Hare had sold a woman's body for £8. It led to an argument between the two men and they came to blows. Burke and his wife moved into the home of his cousin, John Broggan (or Brogan), two streets away from Tanner's Close.[62][63]

The breach between the two men did not last long. In late September or early October Hare was visiting Burke when Mrs Ostler (also given as Hostler), a washerwoman, came to the property to do the laundry. The men got her drunk and killed her; the corpse was with Dr Knox that afternoon, for which the men received £8.[64][65] A week or two later one of McDougal's relatives, Ann Dougal (also given as McDougal) was visiting from Falkirk; after a few days the men killed her by their usual technique and received £10 for the body.[66] Burke later claimed that about this time Margaret Hare suggested killing Helen McDougal on the grounds that "they could not trust her, as she was a Scotch woman", but he refused.[67]

Burke and Hare's next victim was a familiar figure in the streets of Edinburgh, James Wilson, an 18-year-old man with a limp caused by deformed feet. He was mentally disabled and, according to Alanna Knight in her history of the murders, was inoffensive; he was known locally as Daft Jamie.[68] Wilson lived on the streets and supported himself by begging. In November Hare lured Wilson to his lodgings with the promise of whisky, and sent his wife to fetch Burke. The two murderers led Wilson into a bedroom, the door of which Margaret Hare locked before pushing the key back under the door. As Wilson did not like excess whisky—he preferred snuff—he was not as drunk as most of the duo's victims; he was also strong, and fought back against the two attackers, but was overpowered and killed in the normal way. His body was stripped and his few possessions stolen: Burke kept a snuff box and Hare a snuff spoon.[69] When the body was examined the following day by Knox and his students, several of them recognised it to be Wilson, but Knox denied it could be anyone the students knew. When word started circulating that Wilson was missing, Knox dissected the body ahead of the others that were being held in storage; the head and feet were removed before the main dissection.[70][71]

The final victim, killed on 31 October 1828, was Margaret Docherty,[j] a middle-aged Irish woman.[74] Burke lured her into the Broggan lodging house by claiming that his mother was also a Docherty from the same area of Ireland, and the pair began drinking. At one point Burke left Docherty in the company of Helen McDougal while he went out, ostensibly to buy more whisky, but actually to get Hare. Two other lodgers—Ann and James Gray—were an inconvenience to the men, so they paid them to stay at Hare's lodging for the night, claiming Docherty was a relative. The drinking continued into the evening, by which time Margaret Hare had joined in. At around 9:00 pm the Grays returned briefly to collect some clothing for their children, and saw Burke, Hare, their wives and Docherty all drunk, singing and dancing. Although Burke and Hare came to blows at some point in the evening, they subsequently murdered Docherty, and put her body in a pile of straw at the end of the bed.[75][76]

The next day the Grays returned, and Ann became suspicious when Burke would not let her approach a bed where she had left her stockings. When they were left alone in the house in the early evening, the Grays searched the straw and found Docherty's body, showing blood and saliva on the face. On their way to alert the police, they ran into McDougal who tried to bribe them with an offer of £10 a week; they refused.[77] While the Grays reported the murder to the police, Burke and Hare removed the body and took it to Knox's surgery.[k] The police search located Docherty's bloodstained clothing hidden under the bed.[79] Burke and his wife gave different times for Docherty's departure from the house, which raised enough suspicion for the police to take them in for questioning. Early the following morning the police went to Knox's dissecting-rooms where they found Docherty's body; James Gray identified her as the woman he had seen with Burke and Hare. Hare and his wife were arrested that day, as was Broggan; all denied any knowledge of the events.[80]

In total 16 people were murdered by Burke and Hare.[81] Burke stated later that he and Hare were "generally in a state of intoxication" when the murders were carried out, and that he "could not sleep at night without a bottle of whisky by his bedside, and a twopenny candle to burn all night beside him; when he awoke he would take a drink from the bottle—sometimes half a bottle at a draught—and that would make him sleep."[82] He also took opium to ease his conscience.[83]

Developments: investigation and the path to court

On 3 November 1828 a warrant was issued for the detention of Burke, Hare and their wives; Broggan was released without further action.[84][85] The four suspects were kept apart and statements taken; these conflicted with the initial answers given on the day of their arrests.[84] After Dr Alexander Black, a police surgeon, examined Docherty's body, two forensic specialists were appointed, Robert Christison and William Newbigging;[86][l] they reported that it was probable the victim had been murdered by suffocation, but this could not be medically proven.[89] On the basis of the report from the two doctors, the Burkes and Hares were charged with murder.[90] As part of his investigation Christison interviewed Knox, who asserted that Burke and Hare had watched poor lodging houses in Edinburgh and purchased bodies before anyone claimed them for burial. Christison thought Knox was "deficient in principle and heart", but did not think he had broken the law.[91]

Although the police were sure murder had taken place, and that at least one of the four was guilty, they were uncertain whether they could secure a conviction.[92] Police also suspected there had been other murders committed, but the lack of bodies hampered this line of enquiry.[93] As news of the possibility of other murders came to the public's attention, newspapers began to publish lurid and inaccurate stories of the crimes; speculative reports led members of the public to assume that all missing people had been victims. Janet Brown went to the police and identified her friend Mary Paterson's clothing, while a local baker informed them that Jamie Wilson's trousers were being worn by Constantine Burke's son.[94] On 19 November a warrant for the murder of Jamie Wilson was made against the four suspects.[95]

Sir William Rae, the Lord Advocate, followed a regular technique: he focused on one individual to extract a confession on which the others could be convicted. Hare was chosen and, on 1 December, he was offered immunity from prosecution if he turned king's evidence and provided the full details of the murder of Docherty and any other; because he could not be brought to testify against his wife, she was also exempt from prosecution.[92][96] Hare made a full confession of all the deaths and Rae decided sufficient evidence existed to secure a prosecution. On 4 December formal charges were laid against Burke and McDougal for the murders of Mary Paterson, James Wilson and Mrs Docherty.[97][98]

Knox faced no charges for the murders because Burke's statement to the police exonerated the surgeon.[100] Public awareness of the news grew as newspapers and broadsides began releasing further details. Opinion was against the doctor and, according to Bailey, many in Edinburgh thought he was "a sinister ringmaster who got Burke and Hare dancing to his tune".[101] Several broadsides were published with editorials stating that he should have been in the dock alongside the murderers, which influenced public opinion.[100] A new word was coined from the murders: burking, to smother a victim or to commit an anatomy murder,[102][m] and a rhyme began circulating around the streets of Edinburgh:

Up the close and doon the stair,

But and ben' wi' Burke and Hare.

Burke's the butcher, Hare's the thief,

Knox the boy that buys the beef.— 19th century Edinburgh rhyme[94]

Trial

The trial began at 10:00 am on Christmas Eve 1828 before the High Court of Justiciary in Edinburgh's Parliament House. The case was heard by the Lord Justice-Clerk, David Boyle, supported by the Lords Meadowbank, Pitmilly and Mackenzie. The court was full shortly after the doors were opened at 9:00 am,[n] and a large crowd gathered outside Parliament House; 300 constables were on duty to prevent disturbances, while infantry and cavalry were on standby as a further precaution.[104][105]

The case ran through the day and night to the following morning; Rosner notes that even a formal postponement of the case for dinner could have raised questions about the validity of the trial.[106][o] When the charges were read out, the two defence counsels objected to McDougal and Burke being tried together. James Moncrieff, Burke's defence lawyer, protested that his client was charged "with three unconnected murders, committed each at a different time, and at a different place" in a trial with another defendant "who is not even alleged to have had any concern with two of the offences of which he is accused".[108] Several hours were spent on legal arguments about the objection. The judge decided that to ensure a fair trial, the indictment should be split into separate charges for the three murders. He gave Rae the choice as to which should be heard first; Rae opted for the murder of Docherty, given they had the corpse and the strongest evidence.[109][110]

In the early afternoon Burke and McDougal pleaded not guilty to the murder of Docherty. The first witnesses were then called from a list of 55 that included Hare and Knox; not all the witnesses on the list were called and Knox, with three of his assistants, avoided being questioned in court.[111][112] One of Knox's assistants, David Paterson—who had been the main person Burke and Hare had dealt with at Knox's surgery—was called and confirmed the pair had supplied the doctor with several corpses.[113]

In the early evening Hare took the stand to give evidence. Under cross-examination about the murder of Docherty, Hare claimed Burke had been the sole murderer and McDougal had twice been involved by bringing Docherty back to the house after she had run out; Hare stated that he had assisted Burke in the delivery of the body to Knox.[114] Although he was asked about other murders, he was not obliged to answer the questions, as the charge related only to the death of Docherty.[115] After Hare's questioning, his wife entered the witness box, carrying their baby daughter who was suffering from whooping cough. Margaret used the child's coughing fits as a way to give herself thinking time for some of the questions, and told the court that she had a very poor memory and could not remember many of the events.[116][117]

The final prosecution witnesses were the two doctors, Black and Christison; both said they suspected foul play, but that there was no forensic evidence to support the suggestion of murder.[116] There were no witnesses called for the defence, although the pre-trial declarations by Burke and McDougal were read out in their place. The prosecution summed up their case, after which, at 3:00 am, Burke's defence lawyer began his final statement, which lasted for two hours; McDougal's defence lawyer began his address to the jury on his client's behalf at 5:00 am.[118] Boyle then gave his summing up, directing the jury to accept the arguments of the prosecution.[119] The jury retired to consider its verdict at 8:30 am on Christmas Day and returned fifty minutes later. It delivered a guilty verdict against Burke for the murder of Docherty; the same charge against McDougal they found not proven.[p] As he passed the death sentence against Burke, Boyle told him:

Your body should be publicly dissected and anatomized. And I trust, that if it is ever customary to preserve skeletons, yours will be preserved, in order that posterity may keep in remembrance your atrocious crimes.[120]

Aftermath, including execution and dissection

McDougal was released at the end of the trial and returned home. The following day she went to buy whisky and was confronted by a mob who were angry at the not proven verdict. She was taken to a police building in nearby Fountainbridge for her own protection, but after the mob laid siege to it, she escaped through a back window to the main police station off Edinburgh's High Street.[121][122][q] She tried to see Burke, but permission was refused; she left Edinburgh the next day, and there are no clear accounts of her later life.[123] On 3 January 1829, on the advice of both Catholic priests and Presbyterian clergy, Burke made another confession. This was more detailed than the official one provided prior to his trial; he placed much of the blame for the murders on Hare.[124]

On 16 January 1829 a petition on behalf of James Wilson's mother and sister, protesting against Hare's immunity and intended release from prison, was given lengthy consideration by the High Court of Justiciary and rejected by a vote of 4 to 2.[125] Margaret Hare was released on 19 January and travelled to Glasgow to find a passage back to Ireland. While waiting for a ship she was recognised and attacked by a mob. She was given shelter in a police station before being given a police escort onto a Belfast-bound vessel; no clear accounts exist of what became of her after she landed in Ireland.[126]

Burke was hanged on the morning of 28 January 1829 in front of a crowd possibly as large as 25,000;[127][r] views from windows in the tenements overlooking the scaffold were hired at prices ranging from 5 to 20 shillings.[129] On 1 February his corpse was publicly dissected by Professor Monro in the anatomy theatre of the university's Old College.[130] Police had to be called when large numbers of students gathered demanding access to the lecture for which a limited number of tickets had been issued. A minor riot ensued; calm was restored only after one of the university professors negotiated with the crowd that they would be allowed to pass through the theatre in batches of fifty, after the dissection. During the procedure, which lasted for two hours, Monro dipped his quill pen into Burke's blood and wrote "This is written with the blood of Wm Burke, who was hanged at Edinburgh. This blood was taken from his head".[131]

Burke's skeleton was given to the Anatomical Museum of the Edinburgh Medical School where, as of 2018, it remains.[132] His death mask and a book said to be bound with his tanned skin can be seen at Surgeons' Hall Museum.[133][134]

Hare was released on 5 February 1829—his extended stay in custody had been undertaken for his own protection—and was assisted in leaving Edinburgh in disguise by the mailcoach to Dumfries. At one of its stops he was recognised by a fellow-passenger, Erskine Douglas Sandford, a junior counsel who had represented Wilson's family; Sandford informed his fellow passengers of Hare's identity. On arrival in Dumfries the news of Hare's presence spread and a large crowd gathered at the hostelry where he was due to stay the night. Police arrived and arranged for a decoy coach to draw off the crowd while Hare escaped through a back window and into a carriage which took him to the town's prison for safekeeping. A crowd surrounded the building; stones were thrown at the door and windows and street lamps were smashed before 100 special constables arrived to restore order. In the small hours of the morning, escorted by a sheriff officer and militia guard, Hare was taken out of town, set down on the Annan Road and instructed to make his way to the English border.[135] There were no subsequent reliable sightings of him and his eventual fate is unknown.[18][s]

Knox refused to make any public statements about his dealings with Burke and Hare. The common thought in Edinburgh was that he was culpable in the events; he was lampooned in caricature and, in February, a crowd gathered outside his house and burned an effigy of him.[136][t] A committee of inquiry cleared him of complicity, and reported that they had "seen no evidence that Dr Knox or his assistants knew that murder was committed in procuring any of the subjects brought to his rooms".[139] He resigned from his position as curator of the College of Surgeons' museum, and was gradually excluded from university life by his peers. He left Edinburgh in 1842 and lectured in Britain and mainland Europe. While working in London he fell foul of the regulations of the Royal College of Surgeons and was debarred from lecturing; he was removed from the roll of fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1848.[14][140] From 1856 he worked as a pathological anatomist at the Brompton Cancer Hospital and had a medical practice in Hackney until his death in 1862.[14][141]

Legacy

Legislation

The question of the supply of cadavers for scientific research had been promoted by the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham before the crimes of Burke and Hare took place.[u] A parliamentary select committee had drafted a "Bill for preventing the unlawful disinterment of human bodies, and for regulating Schools of Anatomy" in mid 1828—six months before the murders were detected. This was rejected in 1829 by the House of Lords.[4][144]

The murders committed by Burke and Hare raised public awareness of the need for bodies for medical purposes, and of the trade that doctors had conducted with grave robbers and murderers. The East London murder of a 14-year-old boy and the subsequent attempt to sell the corpse to the medical school at King's College London led to an investigation of the London Burkers, who had recently turned from grave robbing to murder to obtain corpses; two men were hanged in December 1831 for the crime. A bill was quickly introduced into Parliament, and gained royal assent nine months later to become the Anatomy Act 1832.[4][145] This Act authorised dissection on bodies from workhouses unclaimed after 48 hours, and ended the practice of anatomising as part of the death sentence for murder.[4][146]

In media portrayals and popular culture

The events of the West Port murders have made appearances in fiction. They are referred to in Robert Louis Stevenson's 1884 short story, "The Body Snatcher", and Marcel Schwob told their story in the last chapter of Imaginary Lives (1896),[147] while the Edinburgh-based author Elizabeth Byrd used the events in her novels Rest Without Peace (1974) and The Search for Maggie Hare (1976).[148] The murders have also been portrayed on stage and screen, usually in heavily fictionalised form.[149][v]

David Paterson, Knox's assistant, contacted Walter Scott to ask the novelist if he would be interested in writing an account of the murders, but he declined, despite Scott's long-standing interest in the events.[158] Scott later wrote:

Our Irish importation have made a great discovery of Oeconomicks, namely, that a wretch who is not worth a farthing while alive, becomes a valuable article when knockd on the head & carried to an anatomist; and acting on this principle, have cleard the streets of some of those miserable offcasts of society, whom nobody missd because nobody wishd to see them again.[159]

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ Gilliland observes that although there is no evidence that the couple had been formally married, they were considered as such under Scottish law.[18]

- ^ It has been suggested that, but for this chance encounter, the public opprobrium which later fell on Knox might have attached to Monro.[27]

- ^ £7 10 shillings in 1827 equates to approximately equivalent to £811 in 2023, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[28]

- ^ The original copy of Hare's confession—given on 1 December and accepted as the basis of his turning king's evidence—was subsequently lost, although the details were widely reported in the press of the time.[33]

- ^ The modern sources that provide a chronological list of the murders are:

- Brian Bailey, Burke and Hare: The Year of the Ghouls; Bailey also tabulates the order from the two Burke confessions, three contemporary publications and his own;[31]

- Lisa Rosner, The Anatomy Murders;[34]

- Owen Dudley Edwards, Burke and Hare.[35]

- ^ Rosner reflects that the pair were unlikely to change their modus operandi for the second murder, particularly for a less effective method of smothering a victim.[37]

- ^ £10 in 1828 equates to approximately £875 in 2016.[28]

- ^ The two women were described in contemporary accounts as prostitutes, but there is no evidence that this was true.[47]

- ^ Some contemporary accounts state that Burke murdered the boy by putting him over his knee and breaking his back; both Rosner and Bailey consider this highly unlikely, and the latter describes it as "a piece of sensational embroidery".[54][57]

- ^ Margaret Docherty's name is also given as Margery, Mary or Madgy with the alternative surname Campbell.[72][73]

- ^ It was a Saturday and the dissecting rooms were closed, so the tea-chest containing the body was left in the cellar; Knox gave the men £5, and told them he would examine it on Monday, when he would pay them the balance.[78]

- ^ During their careers both Newbigging and Christison were Presidents of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh; Christison also became the president of the British Medical Association and one of the personal physicians to Queen Victoria.[87][88]

- ^ The original meaning changed over time in general use as a word for any suppression or cover-up.[102]

- ^ One of the spectators present was Marie Tussaud, also known as Madame Tussaud, who made several sketches during the case. She had a wax model of Burke on display in Liverpool within a fortnight of his execution.[103]

- ^ Burke and McDougal even had their evening meal of soup and bread at 6:00 pm, while they were still in the dock; the case continued while they ate.[107]

- ^ On hearing the not proven verdict Burke turned to McDougal and said "Nelly, you are out of the scrape".[119]

- ^ Some accounts of the escape state that she was disguised as a man for her escape from Fountainbridge, which Rosner considers "picturesque though unlikely".[123]

- ^ One contemporary source, A. Wood's 1829 work West Port Murders, considers the number of attendees "more nearly to forty thousand souls than to thirty-five thousand".[128]

- ^ Several tales of Hare's fate exist. These include that he worked at a lime pit, until he was recognised, upon which point his fellow-workers threw him into the pit, which turned him blind; he may have turned to begging on Oxford Street, London. Other possibilities are that he went to Ireland or America and lived for 40 years after the murders.[18]

- ^ Rosner gives the date as 10 February;[137] Bailey gives 11;[138] Taylor gives 12.[14]

- ^ In order to change public opinion on the matter, Bentham donated his body to be publicly dissected and his corpse to be preserved as an "auto-icon"; it has been on display in University College London since 1850.[142][143]

- ^ On stage:

- The Anatomist (1930) by James Bridie.[150]

- The Doctor and the Devils by Dylan Thomas.[151]

- "The Anatomist" (1937) by James Bridie, adapted for radio by the author[152]

- The Body Snatcher (1945), based on Stevenson's story.[153]

- The Flesh and the Fiends (1960).[150]

- Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971) depicted Burke and Hare in the late Victorian era as employees of Dr. Jekyll.[154]

- Burke & Hare (1971)[155]

- The Doctor and the Devils (1985), based on Thomas's play.[150]

- Burke & Hare (2010).[156]

- "The Anatomist" (1956) an episode of the ITV Play of the Week series.[157]

References

- ^ "The Pioneers of Medical Science in Edinburgh". The British Medical Journal. 2 (761): 135–37. 31 July 1875. JSTOR 25241571.

- ^ a b Bailey 2002, p. 14.

- ^ Roughead 1921, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Goodman, Neville M (23 December 1944). "The Supply of Bodies for Dissection: A Historical Review". The British Medical Journal. 2 (4381): 807–11. JSTOR 20347223.

- ^ Richardson 1987, p. 54.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 17.

- ^ Knight 2007, p. 14.

- ^ Barr 2016, p. 97.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 49.

- ^ Cunningham 2010, p. 229.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Richardson 1987, p. 101.

- ^ Marshall 1995, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor 2004.

- ^ Bates 2010, p. 61.

- ^ Roughead 1921, p. 275.

- ^ Rae 1964, p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gilliland 2004.

- ^ Douglas 1973, p. 30.

- ^ a b Douglas 1973, p. 31.

- ^ Roughead 1921, p. 262.

- ^ a b Rosner 2010, p. 66.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 33.

- ^ Knight 2007, p. 22.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Dudley Edwards 2014, pp. 100–02.

- ^ Roughead 1921, p. 11.

- ^ a b UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Dudley Edwards 2014, pp. 102–03.

- ^ Rosner 2010, p. 251.

- ^ a b Bailey 2002, p. 70.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 233–34.

- ^ a b c d Dudley Edwards 2014, p. 106.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 271–72.

- ^ Dudley Edwards 2014, pp. xx–xxi.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b Rosner 2010, p. 54.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Dudley Edwards 2014, p. 108.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 56–57, 79.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 41–45.

- ^ Dudley Edwards 2014, pp. 107–09.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Roughead 1921, p. 17.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 42, 44.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 116–17.

- ^ Knight 2007, pp. 37–39; Bailey 2002, pp. 45–47; Lonsdale 1870, pp. 101–02.

- ^ a b Knight 2007, p. 41.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 104–05.

- ^ Dudley Edwards 2014, pp. 133–34.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 126–27.

- ^ Dudley Edwards 2014, pp. 115–16.

- ^ a b c Bailey 2002, p. 58.

- ^ a b Knight 2007, p. 45.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 182.

- ^ Rosner 2010, p. 148.

- ^ Roughead 1921, p. 19.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 59.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 148–49.

- ^ Roughead 1921, pp. 267–28.

- ^ Knight 2007, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Rosner 2010, p. 149.

- ^ Rosner 2010, p. 169.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Dudley Edwards 2014, pp. 137–38.

- ^ Roughead 1921, p. 20.

- ^ Knight 2007, p. 51.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 189–90.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 68.

- ^ Rosner 2010, p. 272.

- ^ Dudley Edwards 2014, p. 432.

- ^ Knight 2007, p. 56.

- ^ MacGregor 1884, p. 99.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 72–74.

- ^ Leighton 1861, pp. 198–200.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 76.

- ^ Ward 1998, p. 15.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Wood 1829, p. 202.

- ^ Roughead 1921, p. 270.

- ^ Dudley Edwards 2014, p. 127.

- ^ a b Rosner 2010, p. 215.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 80.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 78.

- ^ White 2004.

- ^

Kaufman, Matthew H (2004). "Peter David Handyside's Diploma as Senior President of the Royal Medical Society". Res Medica. 268 (1). doi:10.2218/resmedica.v268i1.1021. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Knight 2007, p. 69.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Ward 1998, p. 17.

- ^ a b Rosner 2010, pp. 218–19.

- ^ Knight 2007, p. 73.

- ^ a b Bailey 2002, p. 81.

- ^ Rosner 2010, p. 219.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Rosner 2010, p. 221.

- ^ Sharpe 1829, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 114–15.

- ^ a b Knight 2007, p. 87.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 135.

- ^ a b

"burking, n." Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) (subscription required) - ^ Bailey 2002, p. 105.

- ^ Knight 2007, p. 75.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 83.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 212, 225.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 94.

- ^ Sharpe 1829, p. 10.

- ^ Rosner 2010, p. 225.

- ^ Dudley Edwards 2014, pp. 175–76.

- ^ Sharpe 1829, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Knight 2007, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 90.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 95.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 226–27.

- ^ a b Knight 2007, p. 82.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 100–01.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 102–03.

- ^ a b Rosner 2010, p. 230.

- ^ Roughead 1921, pp. 257–58.

- ^ Roughead 1921, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 107–08.

- ^ a b Rosner 2010, p. 232.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 113.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 237–38.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 236–37.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 115–16.

- ^ Wood 1829, p. 233.

- ^ Roughead 1921, p. 64.

- ^ Howard & Smith 2004, p. 54.

- ^ Rosner 2010, p. 244.

- ^

"William Burke". Edinburgh University. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

"Pocketbook made from Burke's skin". Surgeons' Hall Museums. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

"Burke Death Mask". Surgeons' Hall Museums. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Roughead 1921, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 252–53.

- ^ Rosner 2010, p. 253.

- ^ Bailey 2002, p. 146.

- ^ London Medical Gazette 1829, p. 572.

- ^ Bailey 2002, pp. 150–51.

- ^ Rosner 2010, pp. 268–69.

- ^

"Jeremy Bentham auto-icon". University College London. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

"A History of Human Dissection". Royal College of Surgeons of England. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Evans, Alun (2010). "Irish Resurrectionism: 'This Execrable Trade'". Ulster Journal of Archaeology. 69: 155–70. JSTOR 41940979.

- ^ Richardson 1987, pp. 196–97.

- ^ Hutton 2015, p. 4.

- ^ McCracken-Flesher 2012, pp. 106, 139.

- ^ Knight 2007, p. 107.

- ^ McCracken-Flesher 2012, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b c McCracken-Flesher 2012, p. 18.

- ^ Knight 2007, p. 106.

- ^

"'The Anatomist'". BBC Genome. BBC. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McCracken-Flesher 2012, p. 145.

- ^

"Dr Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

"Burke & Hare (1971)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

"Burke & Hare (2010)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

"Towers, Harry Alan (1920–2009)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Knight 2007, p. 103.

- ^ Rosner 2010, p. 74.

Sources

- Bailey, Brian (2002). Burke and Hare: The Year of the Ghouls. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84018-575-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barr, Olivia (2016). A Jurisprudence of Movement: Common Law, Walking, Unsettling Place. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-53184-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bates, Alan (2010). The Anatomy of Robert Knox: Murder, Mad Science and Medical Regulation in Nineteenth-Century Edinburgh. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-84519-381-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cunningham, Andrew (2010). The Anatomist Anatomis'd: An Experimental Discipline in Enlightenment Europe. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-6338-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Douglas, Hugh (1973). Burke and Hare: the true story. London: R. Hale. ISBN 978-0-7091-3777-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dudley Edwards, Owen (2014). Burke and Hare. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-78027-217-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gilliland, J (2004). "Burke, William (1792–1829)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4031. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) (subscription or UK public library membership required) - Howard, Amanda; Smith, Martin (2004). "William Burke and William Hare". River of Blood: Serial Killers and Their Victims. Boca Raton, FL: Universal Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58112-518-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hutton, Fiona (2015). The Study of Anatomy in Britain, 1700–1900. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-31933-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Knight, Alanna (2007). Burke and Hare. London: The National Archives. ISBN 978-1-905615-13-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Leighton, Alexander (1861). The Court of Cacus, or the Story of Burke and Hare. London: Houlston & Wright. OCLC 14825980.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - London Medical Gazette: Or, Journal of Practical Medicine. Vol. 3. London: Longman. 1829. OCLC 477185625.

- Lonsdale, Henry (1870). A Sketch of the Life and Writings of Robert Knox, the Anatomist. London: Macmillan & Co. OCLC 1061812.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - MacGregor, George (1884). The History of Burke and Hare and of the Resurrectionist Times. Glasgow: Thomas Morison. OCLC 60729104.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marshall, Tim (1995). Murdering to Dissect: Grave-robbing, Frankenstein and the Anatomy Literature. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4543-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McCracken-Flesher, Caroline (2012). The Doctor Dissected: A Cultural Autopsy of the Burke and Hare Murders. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-991031-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rae, Isobel (1964). Knox, the Anatomist. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd. OCLC 3165493.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Richardson, Ruth (1987). Death, Dissection and the Destitute. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7102-0919-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rosner, Lisa (2010). The Anatomy Murders. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4191-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Roughead, William (1921). Burke and Hare. Edinburgh: William Hodge & Co. OCLC 60737065.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sharpe, Charles Kirkpatrick, ed. (1829). Trial of William Burke and Helen M'Dougal. Edinburgh: Robert Buchanan, William Hunter, John Stevenson, Baldwin & Cradock. OCLC 506067495.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Taylor, Clare L (2004). "Knox, Robert (1791–1862)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15787. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) (subscription or UK public library membership required) - Ward, Jenny (1998). Crimebusting: breakthroughs in forensic science. London: Blandford. ISBN 978-0-7137-2639-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - White, Brenda M (2004). "Christison, Sir Robert, first baronet (1797–1882)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5370. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) (subscription or UK public library membership required) - Wood, A (1829). West Port Murders. Edinburgh: Thomas Ireland. OCLC 506071737.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Use dmy dates from November 2012

- Articles with inconsistent citation formats

- 1792 births

- 1827 crimes

- 1827 in Scotland

- 1828 in Scotland

- 1829 deaths

- 1859 deaths

- People from County Tyrone

- History of anatomy

- History of Edinburgh

- Murder in Scotland

- Old Town, Edinburgh

- Executed serial killers

- Serial murders in the United Kingdom

- 19th century in Edinburgh

- Crime in Edinburgh

- Criminal duos

- Male serial killers