Voyager 2

Voyager 2 is an unmanned interplanetary spacecraft, launched on August 20, 1977.

It is identical to its sister Voyager program craft, Voyager 1, but unlike Voyager 1, Voyager 2 followed a slower trajectory that allowed it to be kept in the ecliptic (the plane of the Solar System) so that it could be sent to Uranus and Neptune by means of gravity assist during the 1981 encounter at Saturn. Because of this, Voyager 2 could not see the moon Titan up close like its twin, but it allowed the probe to become the first spacecraft to travel to Uranus and Neptune, thus completing a portion of the so-called Planetary Grand Tour, a rare geometric arrangement of the outer planets that only occurs once every 176 years. [1]

Voyager 2 is arguably the most prolific space probe ever launched from Earth, visiting four planets and their many moons with powerful cameras and a multitude of scientific instruments, at a fraction of the money later spent on specialized probes such as the Galileo spacecraft and the Cassini-Huygens probe.

For details on the Voyager instrument package, see the separate article on the Voyager program.

Mission profile

Voyager 2 was originally planned to be Mariner 12, part of the Mariner program.

Voyager 2 was launched on August 20, 1977, from Cape Canaveral, Florida aboard a Titan III-E Centaur rocket.

Ground crews became engrossed in a launch problem with Voyager 1 and forgot to send an important activation code to Voyager 2. This caused the probe to shut down its main high-gain antenna. Fortunately, ground crews were able to establish contact through the craft's low-gain antenna and activate it.

Jupiter

The closest approach to Jupiter occurred on July 9, 1979. It came within 570,000 km (350,000 miles) of the planet's cloud tops. It discovered a few rings around Jupiter. It also took a picture of the moon Io, showing some volcanic activity. That was the first time an active volcano has been observed on another celestial body.

Jupiter is the largest planet in the solar system, composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, with small amounts of methane, ammonia, water vapor, traces of other compounds and a core of melted rock and ice. Colorful latitudinal bands and atmospheric clouds and storms illustrate Jupiter's dynamic weather system. The giant planet is now known to possess 63 moons. The planet completes one orbit of the Sun each 11.8 years and its day is 9 hours, 55 minutes.

Although astronomers had studied Jupiter through telescopes on Earth for centuries, scientists were surprised by many of the Voyager findings.

Voyager's cameras revealed an atmosphere of hydrogen and helium gases, whose clouds were much more dynamic than had been imagined. Jupiter's winds gust at around hundreds of miles per hour, and the red spot alone is three times the size of the Earth (some people have referred to this as the greatest storm in the Solar System). Voyager found why this should be - it found that Jupiter radiates twice as much energy as it receives from the Sun, suggesting that its core must be hot.

Scientists now believe that at the heart of the planet, the gases are compressed until they become a metallic liquid. This hot and churning core could be the powerhouse that drives Jupiter's winds and, like a dynamo, creates a huge magnetic field around the surface of the planet.

The Great Red Spot was revealed as a complex storm moving in a counterclockwise direction. An array of other smaller storms and eddies were found throughout the banded clouds.

Discovery of active volcanism on the satellite Io was easily the greatest unexpected discovery at Jupiter. It was the first time active volcanoes had been seen on another body in the solar system. Together, the Voyagers observed the eruption of nine volcanoes on Io, and there is evidence that other eruptions occurred between the Voyager encounters.

Plumes from the volcanoes extend to more than 300 kilometers (190 miles) above the surface. The Voyagers observed material ejected at velocities up to a kilometer per second.

Io's volcanoes are apparently due to heating of the satellite by tidal pumping. Io is perturbed in its orbit by Europa and Ganymede, two other large satellites nearby, then pulled back again into its regular orbit by Jupiter. This tug-of-war results in tidal bulging as great as 100 meters (330 feet) on Io's surface, compared with typical tidal bulges on Earth of one meter (three feet).

It appears that volcanism on Io affects the entire Jovian system, in that it is the primary source of matter that pervades Jupiter's magnetosphere -- the region of space surrounding the planet influenced by the Jovian magnetic field. Sulfur, oxygen and sodium, apparently erupted by Io's many volcanoes and sputtered off the surface by impact of high-energy particles, were detected as far away as the outer edge of the magnetosphere millions of miles from the planet itself.

Europa displayed a large number of intersecting linear features in the low-resolution photos from Voyager 1. At first, scientists believed the features might be deep cracks, caused by crustal rifting or tectonic processes. The closer high-resolution photos from Voyager 2, however, left scientists puzzled: The features were so lacking in topographic relief that as one scientist described them, they "might have been painted on with a felt marker." There is a possibility that Europa may be internally active due to tidal heating at a level one-tenth or less than that of Io. Europa is thought to have a thin crust (less than 30 kilometers or 18 miles thick) of water ice, possibly floating on a 50-kilometer-deep (30-mile) ocean.

Ganymede turned out to be the largest moon in the solar system, with a diameter measuring 5,276 kilometers (3,280 miles). It showed two distinct types of terrain -- cratered and grooved -- suggesting to scientists that Ganymede's entire icy crust has been under tension from global tectonic processes.

Callisto has a very old, heavily cratered crust showing remnant rings of enormous impact craters. The largest craters have apparently been erased by the flow of the icy crust over geologic time. Almost no topographic relief is apparent in the ghost remnants of the immense impact basins, identifiable only by their light color and the surrounding subdued rings of concentric ridges.

A faint, dusty ring of material was found around Jupiter. Its outer edge is 129,000 kilometers (80,000 miles) from the center of the planet, and it extends inward about 30,000 kilometers (18,000 miles).

Two new, small satellites, Adrastea and Metis, were found orbiting just outside the ring. A third new satellite, Thebe, was discovered between the orbits of Amalthea and Io.

Jupiter's rings and moons exist within an intense radiation belt of electrons and ions trapped in the planet's magnetic field. These particles and fields comprise the Jovian magnetosphere, or magnetic environment, which extends three to seven million kilometers toward the Sun, and stretches in a windsock shape at least as far as Saturn's orbit -- a distance of 750 million kilometers (460 million miles).

As the magnetosphere rotates with Jupiter, it sweeps past Io and strips away about 1,000 kilograms (one ton) of material per second. The material forms a torus, a doughnut-shaped cloud of ions that glow in the ultraviolet. The torus's heavy ions migrate outward, and their pressure inflates the Jovian magnetosphere to more than twice its expected size. Some of the more energetic sulfur and oxygen ions fall along the magnetic field into the planet's atmosphere, resulting in auroras.

Io acts as an electrical generator as it moves through Jupiter's magnetic field, developing 400,000 volts across its diameter and generating an electric current of 3 million amperes that flows along the magnetic field to the planet's ionosphere.

Voyager 2 left Jupiter a couple of days after arriving. The space probe was able to take many photographs of the planet.

Saturn

The closest approach to Saturn occurred on August 25, 1981.

While behind Saturn (as viewed from Earth), Voyager 2 probed Saturn's upper atmosphere with its radar, to measure temperature and density profiles. Voyager 2 found that at the highest levels (7 kilopascals pressure) Saturn's temperature was 70 Kelvin (−203 °C), while at the deepest levels measured (120 kilopascals) the temperature increased to 143 Kelvin (−130 °C). The north pole was found to be 10 Kelvin cooler, although this may be seasonal (see also Saturn Oppositions).

After the Saturn fly-by, the camera platform on Voyager 2 locked up briefly, putting plans to officially extend the mission to Uranus and Neptune in jeopardy. Fortunately, the mission team was able to fix the problem--caused by overuse that temporarily depleted its lubricant--and the probe was given the go-ahead to examine Uranus.

As the Voyager craft encountered the planet itself, it was revealed that Saturn was made of the same gases as Jupiter. These two worlds are known as the great gas giants, dwarfing all the other planets.

However, Saturn held mysteries of its own. Saturn is smaller and colder than Jupiter, it generates less heat within, and receives less energy from The Sun. Yet Voyager recorded even faster winds on Saturn than on Jupiter (around 1000 miles an hour). At the time of this discovery, why this should be, was not yet understood.

After it left Saturn there was one final encounter. Titan, Saturn's largest moon, is the only moon in the solar system with a thick atmosphere. The cameras could not penetrate through the red-orange haze to see what lay beneath.

-

Saturn taken by Voyager 2.

-

Iapetus by Voyager 2 spacecraft, August 22, 1981.

-

Color image of Enceladus, almost full disk.

-

Titan.

Uranus

The closest approach to Uranus occurred on January 24, 1986.

Voyager 2 discovered 10 previously unknown moons; studied the planet's unique atmosphere, caused by its axial tilt of 97.77°; and examined its ring system.

In its first solo planetary flyby, Voyager 2 made its closest approach to Uranus on January 24, 1986, coming within 81,500 kilometers (50,600 miles) of the planet's cloud tops.

Uranus is the third largest planet in the solar system. It orbits the Sun at a distance of about 2.8 billion kilometers (1.7 billion miles) and completes one orbit every 84 years. The length of a day on Uranus as measured by Voyager 2 is 17 hours, 14 minutes.

Uranus is distinguished by the fact that it is tipped on its side. Its unusual position is thought to be the result of a collision with a planet-sized body early in the solar system's history. Given its odd orientation, with its polar regions exposed to sunlight or darkness for long periods, scientists were not sure what to expect at Uranus.

Voyager 2 found that one of the most striking influences of this sideways position is its effect on the tail of the magnetic field, which is itself tilted 60 degrees from the planet's axis of rotation. The magnetotail was shown to be twisted by the planet's rotation into a long corkscrew shape behind the planet.

Voyager had found a very different kind of giant, a world many times smaller and colder than Jupiter and Saturn. It was shrouded in different gases, mostly methane and ammonia, under which scientists believe there might lie oceans of water and ice.

The presence of a magnetic field at Uranus was not known until Voyager's arrival. The intensity of the field is roughly comparable to that of Earth's, though it varies much more from point to point because of its large offset from the center of Uranus. The peculiar orientation of the magnetic field suggests that the field is generated at an intermediate depth in the interior where the pressure is high enough for water to become electrically conducting.

Radiation belts at Uranus were found to be of an intensity similar to those at Saturn. The intensity of radiation within the belts is such that irradiation would quickly darken (within 100,000 years) any methane trapped in the icy surfaces of the inner moons and ring particles. This may have contributed to the darkened surfaces of the moons and ring particles, which are almost uniformly gray in color.

A high layer of haze was detected around the sunlit pole, which also was found to radiate large amounts of ultraviolet light, a phenomenon dubbed "dayglow." The average temperature is about 60 kelvins (-350 degrees Fahrenheit). Surprisingly, the illuminated and dark poles, and most of the planet, show nearly the same temperature at the cloud tops.

Voyager found 10 new moons, bringing the total number to 15 at those times. Most of the new moons are small, with the largest measuring about 150 kilometers (about 90 miles) in diameter.

The moon Miranda, innermost of the five large moons, was revealed to be one of the strangest bodies yet seen in the solar system. Detailed images from Voyager's flyby of the moon showed huge fault canyons as deep as 20 kilometers (12 miles), terraced layers, and a mixture of old and young surfaces. One theory holds that Miranda may be a reaggregation of material from an earlier time when the moon was fractured by a violent impact.

The five large moons appear to be ice-rock conglomerates like the satellites of Saturn. Titania is marked by huge fault systems and canyons indicating some degree of geologic, probably tectonic, activity in its history. Ariel has the brightest and possibly youngest surface of all the Uranian moons and also appears to have undergone geologic activity that led to many fault valleys and what seem to be extensive flows of icy material. Little geologic activity has occurred on Umbriel or Oberon, judging by their old and dark surfaces.

All nine previously known rings were studied by the spacecraft and showed the Uranian rings to be distinctly different from those at Jupiter and Saturn. The ring system may be relatively young and did not form at the same time as Uranus. Particles that make up the rings may be remnants of a moon that was broken by a high-velocity impact or torn up by gravitational effects.

-

Uranus viewed from 18 million kilometers.

-

A photo of Uranus taken by Voyager 2.

-

Uranus Final Image.

-

Voyager 2 shot of the Uranian rings.

Neptune

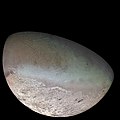

The closest approach to Neptune occurred on August 25, 1989. Since this was the last major planet Voyager 2 could visit, it was decided to make a close flyby of the moon Triton, regardless of the consequences to the trajectory, as with Voyager 1's encounter with Saturn and its moon Titan.

The probe also discovered the Great Dark Spot, which has since disappeared, according to Hubble Space Telescope observations. Originally thought to be a large cloud itself, it was later postulated to be a hole in the visible cloud deck.

Neptune turned out to have the strongest winds of all the solar system's gas giants. In the outer regions of the solar system, where the Sun shines feebly, the last of the four giants defied all expectations of the scientists.

One might expect that the farther one gets from The Sun, the less energy there would be to drive the winds around. The winds on Jupiter were already hundreds of kilometers per hour. Rather than seeing slower winds, the scientists found faster winds (over 1600 km/h) on more distant Neptune.

Scientists now know why this is the case —if enough energy is produced, turbulence is created, which slows the winds down (like those of Jupiter). At Neptune however, there is so little energy, that once winds are started, they never slow down.

Following Voyager 2's fly-by of Neptune, Pluto remained the only planet to not be visited by a probe from Earth, although in 2006 the International Astronomical Union came up with a new definition of "planet" which demoted Pluto to "dwarf planet" status. As a result of this, the 1989 fly-by of Neptune by Voyager 2 became the point when every planet in the solar system had now been visited at least once by spacecraft.

-

Voyager 2 image of Neptune

-

Voyager 2 image of Triton

Escaping the solar system

Voyager reached the extremes of the solar system, and revealed not only the gas giants themselves, but whole new systems of rings and moons. As the planets moved out of their alignment, Uranus and Neptune once again drifted out of reach.

Since its planetary mission is over, Voyager 2 is now described as working on an Interspace Mission, which NASA is using to find out what the solar system is like beyond the heliosphere. Unlike Voyager 1, which is believed to have crossed the termination shock into the heliosheath in December 2004, Voyager 2 is currently not believed to have left the heliosphere yet. In addition, each Voyager carries a gold-plated audio-visual disc just in case either spacecraft is ever found by intelligent aliens. The disc carries images of Earth and it's lifeforms, a range of scientific information, and a medley, 'Sounds of Earth', that includes the sounds of whales, a baby crying, waves breaking on a shore and a variety of music.

As of September 5, 2006, Voyager 2 is at a distance of around 80.5 AU (approximately 12 terameters) from the Sun, deep in the scattered disc, and traveling outward at roughly 3.3 AUs a year. It is more than twice the distance from the Sun as Pluto, and far beyond the perihelion of 90377 Sedna, but not yet beyond the outer limits of the orbit of Eris.

Voyager 2 is expected to keep on transmitting into the 2030s.

| Year | End of specific capabilities as a result of the available electrical power limitations |

|---|---|

| 1998 | Terminate scan platform and UV observations |

| ~2012 | Termination of gyro operations |

| ~2012 | Termination of DTR operations (limited by ability to capture 1.4 kbit/s data using a 70 m/34 m antenna array) |

| ~2016 | Initiate instrument power sharing |

| > 2020 | Can no longer power any single instrument |

Current status

Voyager 2, as of April 2006, is at −52.51° declination and 19.775 h Right Ascension, placing it in the constellation Telescopium.

As of July 14, 2006, Voyager 2 was 7,367,000,000 miles from Earth [2].

Information about ongoing telemetry exchanges with Voyager 2 is available from Voyager Weekly Reports. [3]

Voyager 2 in fiction and popular culture

- This section contains specific references to Voyager 2. For other references to the Voyagers, see Voyager in fiction and popular culture in the Voyager program article.

- "Voyager 2"-Title of a song by band, Virginia Coalition. Appeared on "Ok To Go" Album.

- The motion picture Starman portrayed Voyager 2 as having been located by an alien intelligence who subsequently sent one of their own race to investigate intelligent life on Earth.

- In the episode "Parasites Lost" of the animated show Futurama, Leela scrubs the remains of Voyager 2 off the windscreen of her spaceship while refueling at an interplanetary service station.

- The introduction movie for the computer game Battlezone II depicts Voyager 2 as a discreetly armed reconnaissance probe, and is subsequently destroyed by an anti-satellite missile after discovering a secret military base on the undiscovered Dark Planet.

- In the television series "Beast Wars" Megatron mentions that the Golden Disk (which was a major plot element of the second season) shown in the series was from the Voyager 2 (and even shows an animated Voyager 2 launching from earth)

See also

- Voyager program for more information about this spacecraft.

- Voyager Golden Record

- Voyager 1

- Pioneer 10

- Pioneer 11

References

- "Saturn Science Results". Voyager Science Results at Saturn. Retrieved February 8.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Uranus Science Results". Voyager Science Results at Uranus. Retrieved February 8.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

External links

- NASA Voyager website

- Voyager Spacecraft Lifetime

- Spacecraft Escaping the Solar System - current positions and diagrams

- Mission state

- Voyager 2 Detects Odd Shape of Solar System's Edge 23 May 2006