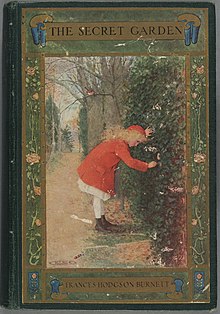

The Secret Garden

Front cover of the US edition | |

| Author | Frances Hodgson Burnett |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | M. L. Kirk (US) Charles Robinson (UK)[1] |

| Genre | Children's novel |

| Publisher | Frederick A. Stokes (US) William Heinemann (UK)[2] |

Publication date | 1911 (UK[2] & US[1]) |

| Publication place | UK and US |

| Pages | 375 (UK[2] & US[3]) |

| LC Class | PZ7.B934 Se 1911[3] |

The Secret Garden is a novel by Frances Hodgson Burnett first published in book form in 1911, after serialization in The American Magazine (November 1910 – August 1911). Set in England, it is one of Burnett's most popular novels and seen as a classic of English children's literature. Several stage and film adaptations have been made. The American edition was published by the Frederick A. Stokes Company with illustrations by Maria Louise Kirk (signed as M. L. Kirk), and the British edition by Heinemann with illustrations by Charles Heath Robinson.[1][4]

Plot summary

At the turn of the 20th century, Mary Lennox is a sickly, neglected, and unloved 10-year-old girl, born in India to wealthy British parents who never wanted her, and made an effort to ignore the girl. She is cared for primarily by native servants, who allow her to become spoiled, aggressive, and self-centered. After a cholera epidemic kills her parents and the servants, Mary is discovered alive but alone in the empty house. She briefly lives with an English clergyman and his family in India before she is sent to Yorkshire, in England, to live with Mr. Archibald Craven, a wealthy, hunchbacked uncle whom she has never met, at his isolated house, Misselthwaite Manor.

At first, Mary is as obnoxious and sour as ever. She dislikes her new home, the people living in it, and most of all, the bleak moor on which it sits. She only begins to like a good-natured maid named Martha Sowerby, who tells Mary about Mary's aunt, the late Lilias Craven, who would spend hours in a private walled garden growing roses. Mrs Craven died after an accident in the garden, and the devastated Mr Craven locked the garden and buried the key. Mary becomes interested in finding the secret garden herself, and her ill manners begin to soften as a result. Soon she comes to enjoy the company of Martha, the gardener Ben Weatherstaff, and a friendly robin redbreast. Her health and attitude improve with the bracing Yorkshire air, and she grows stronger as she explores the moor and plays with a skipping rope that Mrs.Sowerby buys for her. Mary wonders about both the secret garden and the mysterious cries that echo through the house at night.

As Mary explores the gardens, her robin draws her attention to an area of disturbed soil. Here Mary finds the key to the locked garden and eventually the door to the garden itself. She asks Martha for garden tools, which Martha sends with Dickon, her 12-year-old brother who spends most of his time out on the moors. Mary and Dickon take a liking to each other, as Dickon has a kind way with animals and a good nature. Eager to absorb his gardening knowledge, Mary tells him about the secret garden.

One night, Mary hears the cries once more and decides to follow them through the house. She is startled when she finds a boy her age named Colin, who lives in a hidden bedroom. She soon discovers that they are cousins, Colin being the son of Mr. and Mrs. Craven, and that he suffers from an unspecified spinal problem which precludes him from walking and causes him to spend most of his time in bed. Mary visits him every day that week, distracting him from his troubles with stories of the moor, Dickon and his animals, and the secret garden. Mary finally confides that she has access to the secret garden, and Colin asks to see it. Colin is put into his wheelchair and brought outside into the secret garden. It is the first time he has been outdoors for several years.

While in the garden, the children look up to see Ben Weatherstaff looking over the wall on a ladder. Startled and angry to find the children in the secret garden, he admits that he believed Colin to be a cripple. Colin stands up from his chair and finds that his legs are fine, though weak from long disuse. Colin and Mary soon spend almost every day in the garden, sometimes with Dickon as company. The children and Ben conspire to keep Colin's recovering health a secret from the other staff, so as to surprise his father, who is travelling abroad. As Colin's health improves, his father sees a coinciding increase in spirits, culminating in a dream where his late wife calls to him from inside the garden. When he receives a letter from Mrs Sowerby, he takes the opportunity finally to return home. He walks the outer garden wall in his wife's memory, but hears voices inside, finds the door unlocked, and is shocked to see the garden in full bloom, and his son healthy, having just won a race against Mary. The servants watch, stunned, as Mr Craven and Colin walk back to the manor together.

Rejuvenation theme

The secret garden at Misselthwaite Manor is the site of both the near-destruction and the subsequent regeneration of a family.[5] Another theme is when a thing is neglected it withers and dies, but when it is worked on and cared for it thrives, as Mary and Colin do.

Background

The book's working title was Mistress Mary, in reference to the English nursery rhyme Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary. Parts of it were written during Burnett's visits to Buile Hill Park,[6] Maytham Hall in Kent, England, where Burnett lived for a number of years during her marriage, is often cited as the inspiration for the book's setting.[7] Burnett kept an extensive garden, including an impressive rose garden. However, it has been noted that besides the garden, Maytham Hall and Misselthwaite Manor are physically very different.[7]

Publication history

The Secret Garden was first serialised in ten issues (November 1910 – August 1911) of The American Magazine, with illustrations by J. Scott Williams.[8] It was first published in book form in August 1911 by the Frederick A. Stokes Company in New York;[9] it was also published that year by William Heinemann in London. Its copyright expired in the United States in 1987, and in most other parts of the world in 1995, placing the book in the public domain. As a result, several abridged and unabridged editions were published during the late 1980s and early 1990s, such as the full-color illustrated edition from David R. Godine, Publisher in 1989.

Inga Moore's abridged edition of 2008, illustrated by her, is arranged so that a line of the text also serves as a caption to a picture.

Public reception

Marketing to both adult and juvenile audiences may have had an effect on its early reception; the book was not as celebrated as Burnett's previous works during her lifetime.[10] The Secret Garden paled in comparison to the popularity of Burnett's other works for a long period. Tracing the book's revival from almost complete eclipse at the time of Burnett's death in 1924, Anne H. Lundin noted that the author's obituary notices all remarked on Little Lord Fauntleroy and passed over The Secret Garden in silence.[11]

With the rise of scholarly work in children's literature over the past quarter-century, The Secret Garden has risen steadily in prominence. It is often noted as one of the best children's books of the twentieth century.[10] In 2003 it ranked number 51 in The Big Read, a survey of the British public by the BBC to identify the "Nation's Best-loved Novel" (not children's novel).[12] Based on a 2007 online poll, the U.S. National Education Association named it one of "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children".[13] In 2012 it was ranked number 15 among all-time children's novels in a survey published by School Library Journal, a monthly with primarily U.S. audience.[14] (A Little Princess was ranked number 56 and Little Lord Fauntleroy did not make the Top 100.)[14] Jeffrey Masson considers The Secret Garden "one of the greatest books ever written for children".[15] In an oblique compliment, Barbara Sleigh has her title character reading The Secret Garden on the train at the beginning of her children's novel Jessamy.[16]

Adaptations

Film

The first filmed version was made in 1919 by the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation with 17-year-old Lila Lee as Mary and Paul Willis as Dickon, but the film is thought lost.

In 1949, MGM filmed the second adaptation with Margaret O'Brien as Mary, Dean Stockwell as Colin and Brian Roper as Dickon. This version was mostly in black-and-white, but the sequences set in the restored garden were filmed in Technicolor. Noel Streatfeild's 1948 novel The Painted Garden deals with making of this film.

American Zoetrope's 1993 production was directed by Agnieszka Holland, with a screenplay by Caroline Thompson, and starred Kate Maberly as Mary, Heydon Prowse as Colin, Andrew Knott as Dickon, John Lynch as Lord Craven and Dame Maggie Smith as Mrs. Medlock. The executive producer was Francis Ford Coppola.

The 2020 film version from Heyday Films and StudioCanal is directed by Marc Munden with a screenplay by Jack Thorne.[17]

Television

Dorothea Brooking adapted the book into several different television serials for the BBC: an eight-part serial in 1952, an eight-part serial in 1960 (starring Colin Spaull as Dickon) and a seven-part serial broadcast in 1975, which last has been released on DVD.[18]

Hallmark Hall of Fame filmed a TV adaptation of the novel in 1987, starring Gennie James as Mary, Barret Oliver as Dickon, and Jadrien Steele as Colin. Billie Whitelaw appeared as Mrs Medlock and Derek Jacobi played the role of Archibald Craven, with Alison Doody appearing in flashbacks and visions as Lilias; Colin Firth made a brief appearance as the adult Colin Craven. The story was changed slightly, with Colin's father, instead of being Mary's uncle, being an old friend of Mary's father, allowing Colin and Mary to start a relationship as adults by the film's end. It was filmed at Highclere Castle, which later became known as the filming location for Downton Abbey.

A 1994 animated adaptation as an ABC Weekend Special starred Honor Blackman as Mrs. Medlock, Derek Jacobi as Archibald Craven, Glynis Johns as Darjeeling, Victor Spinetti, Anndi McAfee as Mary Lennox, Joe Baker as Ben Weatherstaff, Felix Bell as Dickon Sowerby, Naomi Bell as Martha Sowerby, Richard Stuart as Colin Craven, and Frank Welker as Robin. This version was released on video in 1995 by ABC Video.[19][20]

In Japan, NHK produced and broadcast an anime adaptation of the novel in 1991–1992 titled Anime Himitsu no Hanazono (アニメ ひみつの花園). Miina Tominaga was featured as the voice of Mary, while Mayumi Tanaka voiced Colin. The 39-episode TV series was directed by Tameo Kohanawa and written by Kaoru Umeno. Based on the title, this anime is sometimes mistakenly assumed to be related to the popular dorama series Himitsu no Hanazono. Unavailable in the English language, it has been dubbed into several other languages including Spanish, Italian, Polish and Tagalog.

Theatre

A Theatre for Young Audiences version was written in 1991 by Pamela Sterling of Arizona State University. The adaptation won an American Alliance for Theatre and Education "Distinguished New Play" award and is listed in ASSITEH/USA's International Bibliography of Outstanding Plays for Young Audiences.[21] Stage adaptations of the book have also been created. In 1991, a musical version opened on Broadway, with music by Lucy Simon, and book and lyrics by Marsha Norman. The production was nominated for seven Tony Awards, winning Best Book of a Musical and Best Featured Actress in a Musical for Daisy Eagan as Mary, then eleven years old. In 2013 an opera by the American composer Nolan Gasser, which had been commissioned by the San Francisco Opera, premiered at the Zellerbach Hall at the University of California, Berkeley.

A stage play by Jessica Swale adapted from the novel was performed at Grosvenor Park Open Air Theatre in Chester 2014.[22]

Other

A multimedia web series adaptation of the novel titled The Misselthwaite Archives was released on YouTube in 2015. The series consisted of 40 episodes, which aired from January through October, as well as fictional letters, emails, text messages, social media accounts, and other documents about the characters.[23][24]

References

- ^ a b c The Secret Garden title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ^ a b c "British Library Item details". primocat.bl.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ a b The Secret Garden (first edition). Library of Congress Online Catalog. LCCN Permalink (lccn.loc.gov). Retrieved 2017-03-24. The catalog record reports 4 leaves of plates, 4 color illustrations (uncredited).

- ^ WorldCat library records:

OCLC 1289609, OCLC 317817635 (US); OCLC 8746090 (UK).

Retrieved 2017-03-24. - ^ Gohike, M. (1980). Re-Reading The Secret Garden. College English 41 (8), 894–902.

- ^ "Buile Hill Park". Salford Borough Council. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ a b Thwaite, A. (2006). A Biographer Looks Back. A.S. Carpenter (ed.) Toronto: Scarecrow Press.

- ^ "The American Magazine, November 1910". FictionMags Index. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ "New York Literary Notes". The New York Times. 16 July 1911. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ a b Lundin, A. (2006). "The Critical and Commercial Reception of The Secret Garden". In the Garden: Essays in Honour of Frances Hodgson Burnett. Angelica Shirley Carpenter (ed.) Toronto: Scarecrow Press.

- ^ Lundin, A. Constructing the Canon of Children's Literature: Beyond Library Walls :133ff.

- ^ "BBC – The Big Read". BBC. April 2003, Retrieved 18 October 2012

- ^ National Education Association (2007). "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children". Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ a b Bird, Elizabeth (7 July 2012). "Top 100 Chapter Book Poll Results". A Fuse #8 Production. Blog. School Library Journal (blog.schoollibraryjournal.com). Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Masson, Jeffrey Moussaieff (1980). The Oceanic Feeling: The Origins of Religious Sentiment in Ancient India. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel. ISBN 90-277-1050-3.

- ^ Barbara Sleigh: Jessamy (London: Collins, 1967), p. 7.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (20 January 2018). "Marc Munden To Helm The Secret Garden For David Heyman & Studiocanal". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ Traxy (16 January 2011). "The Secret Garden (1975)". Thesqueee.co.uk. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ ABC Weekend Specials: The Secret Garden (TV episode 1994) at IMDb

- ^ Lynne Heffley (4 November 1994). "TV Review: Animated 'Garden' Wilts on ABC". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ https://www.dramaticpublishing.com/browse/full-length-plays/the-secret-garden

- ^ http://www.grosvenorparkopenairtheatre.co.uk/portfolio/the-secret-garden-5/

- ^ "The Misselthwaite Archives".

- ^ The Misselthwaite Archives at IMDb

External links

- The Secret Garden at Project Gutenberg (plain text and HTML illustrated)

- The Secret Garden, available at Internet Archive. New York : F. A. Stokes, 1911 (color scanned book)

The Secret Garden public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Secret Garden public domain audiobook at LibriVox- The Secret Garden From the Collections at the Library of Congress

- 1911 American novels

- 1911 British novels

- American children's novels

- American novels adapted into films

- American novels adapted into plays

- British children's novels

- British novels adapted into films

- British novels adapted into plays

- Novels by Frances Hodgson Burnett

- Novels first published in serial form

- Novels adapted into television programs

- Works originally published in The American Magazine

- Novels about orphans

- Novels set in Yorkshire

- Heinemann (publisher) books

- 1911 children's books

- ABC Weekend Special