Mary Wollstonecraft

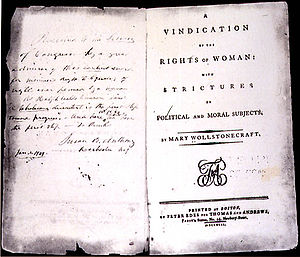

Mary Wollstonecraft (April 27, 1759 – September 10, 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and early feminist. During her brief career, she wrote novels, treatises, a travel narrative, a history, a conduct book, and a children's book, but is best known for her A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. In the latter, Wollstonecraft argued that women's inferiority was not natural but was rather a consequence of their miseducation, a miseducation imposed on them by men. She suggested, therefore, that both men and women should receive a rational education and she imagined a social order founded on reason and free from prejudice.

In addition to Wollstonecraft's literary work, her life itself has been a topic of considerable interest due to her struggle against numerous hardships and her unconventional, and often tumultuous, relationships. Wollstonecraft married the philosopher William Godwin, one of the forefathers of the anarchist movement, and was the mother of Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein. Wollstonecraft died tragically at the age of thirty-eight due to complications from childbirth, leaving behind several unfinished manuscripts.

Today, Wollstonecraft is widely considered one of the founders of feminist philosophy. Her early advocacy of women's equality, and her attacks on conventional femininity and the degradation of women presaged the later emergence of a feminist political movement. Both Wollstonecraft's ideas and her personal struggles as a woman have been cited as important influences by later feminist writers and activists.

Early life

Mary Wollstonecraft was born on April 27, 1759 in Spitalfields, England. Although her family had a comfortable income when she was a young child, her father gradually wasted it on speculative projects. The family was consequently emotionally and financially unstable; they were constantly moving during Wollstonecraft's youth.[1] The family's financial situation eventually became so dire that Wollstonecraft's father forced her to turn over money that she would have inherited at her maturity. Moreover, he appears to have been a violent man, beating his wife in drunken rages. As a teenager, Wollstonecraft used to lie outside the door of her mother’s bedroom to protect her.[2] Wollstonecraft also played this protective maternal role for her sisters, Everina and Eliza, throughout her life. In a dramatic and defining moment in 1784, she convinced and helped her sister Eliza, who was suffering from what was probably post-partum depression, to leave her husband and infant. With this action, Wollstonecraft demonstrated that she was willing to challenge social norms, but the human costs were severe: her sister was doomed to a life of poverty and hard work (as she could not remarry) as well as social condemnation.[3]

Wollstonecraft had two friendships that shaped her early life. The first was with Jane Arden in Beverley. She wrote to her “I have formed romantic notions of friendship… I am a little singular in my thoughts of love and friendship; I must have the first place or none."[4] The second and more important was with Fanny Blood. Wollstonecraft credited Fanny with opening her mind to new possibilities; in the end, though, she discovered that she had idealized Fanny, but she remained dedicated to her and her family. Wollstonecraft, her two sisters Eliza and Everina, and Fanny set up a school together in Newington Green, a dissenting community, but it failed after Wollstonecraft abandoned it to look after Fanny.[5] Fanny had become engaged and after her husband, Hugh Skeys, took her to the continent to improve her health,[6] she became pregnant and her health worsened; Wollstonecraft followed in 1785 to nurse her.[7] Fanny's death devastated Wollstonecraft and was part of the inspiration for her first novel, Mary.

“The first of a new genus”

After Fanny died and Wollstonecraft returned to England, she worked as a governess for the Kingsborough family for a year in Ireland but she could not get along with Lady Kingsborough,[8] although the children seem to have found her an inspiring instructor. Margaret King would later say she "had freed her mind from all superstitions."[9] Some of what Wollstonecraft learned during this experience would make its way into her only children's book, Original Stories from Real Life (1788). The book went through nine editions before eventually going out of print in 1818[10]; the second edition, printed in 1791, carried engravings by William Blake.

Frustrated by the limited career options open to respectable yet poor women, a frustration which she eloquently described in the chapter of Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787) entitled "Unfortunate Situation of Females, Fashionably Educated, and Left Without a Fortune", Wollstonecraft decided to embark upon a career as an author. It was a truly radical decision since few women could support themselves by writing at the time. As she wrote to her sister Everina in 1787, she was trying to become “the first of a new genus”.[11] She moved to London and, assisted by the liberal publisher Joseph Johnson, found a place to live and work to support herself.[12] She translated texts (learning French and German to do so[13]), most notably Of the Importance of Religious Opinions by Jacques Necker and Elements of Morality, for the Use of Children by Christian Gotthilf Salzmann, and wrote reviews, mostly on novels, for the Analytical Review, a Johnson publication.[14] Wollstonecraft’s intellectual universe greatly expanded during this time, not only from the reading that she did for her reviews but also from the company that she started keeping. She attended Johnson’s famous dinners and met such luminaries as Thomas Paine and William Godwin.

While in London, Wollstonecraft pursued a relationship with the artist Henry Fuseli, even though he was already married. She was enraptured by his genius, “the grandeur of his soul, that quickness of comprehension, and lovely sympathy,” as she said.[15] She seems to have proposed a platonic threesome arrangement but Fuseli’s wife was appalled and Fuseli broke the relationship off.[16] After Fuseli’s rejection, Wollstonecraft decided to travel to France not only to escape the humiliation of the incident (which was widely known) but also to participate in the exciting revolutionary events which she had just celebrated in her recent Vindication of the Rights of Men, a response to Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), and more indirectly in her A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792).

Throughout her life, Wollstonecraft was plagued by what was probably depression. Her letters to her sisters and close friends are not elegant and closely crafted missives (the more usual eighteenth century style of letter-writing)—they are outpourings of emotion in which her agony and misery are clear. She frequently resolves to accept God’s punishment and is anxious for death to come. Wollstonecraft's depressive crisis seem to have crested whenever she was rejected, by a close friend, such as Jane Arden, or by a lover.[17]

France and Imlay

Wollstonecraft left for Paris in December of 1792 and she arrived about a month before Louis XVI was guillotined—the country was in turmoil. She sought out other English visitors such as Helen Maria Williams and joined the circle of expatriates then in the city[18]. Having just written A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft seemed determined to put her ideas to the test and in the stimulating intellectual atmosphere of the French Revolution, she attempted her most experimental romantic attachment yet. She met and fell passionately in love with Gilbert Imlay, an American adventurer.[19] Whether or not Wollstonecraft was interested in marriage, it seems clear that Imlay was not, and Wollstonecraft appears to have fallen in love with a idealized portrait of the man she met.[20] Moreover, while Wollstonecraft had rejected the sexual component of relationships in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Imlay awakened her passions and her interest in sex.[21] Wollstonecraft soon became pregnant and on May 14, 1794, she gave birth to her first child, Fanny, naming her after her first and perhaps closest friend.[22] Wollstonecraft never ceased to be a writer, though. While in France, she gathered information for her version of a history of the early Revolution; she wrote avidly at Le Havre. In December of 1794, An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution was published in London.

As the political situation worsened and England declared war on France, all English citizens in France were put at considerable risk. To protect Wollstonecraft, Imlay registered her as his wife in 1793 even though they were not married.[23] Some of Wollstonecraft’s friends were not so lucky: many were arrested, like Thomas Paine, and some were even guillotined. After Wollstonecraft left France, she continued to refer to herself as “Mrs. Imlay”, even to her sisters, in order to grant legitimacy to her child.[24]

Imlay, unhappy with the domesticated and maternal Wollstonecraft, eventually left her. He promised that he would return to Le Havre, France, where she went to give birth to her child, but his long delays in writing to her and his long absences convinced the anxious and distraught Wollstonecraft that he had found another woman. Her letters to him are full of needy expostulations, explained by some critics as the expressions of a deeply depressed woman but perhaps understandable under the circumstances—she was alone with an infant in the middle of a revolution.[25]

England and Godwin

Seeking Imlay, Wollstonecraft returned to London in April of 1795, but he rejected her. In May of 1795 she attempted to commit suicide, probably with laudanum, but Imlay saved her life (it is unclear how).[26] In one last attempt to win back Imlay, she embarked upon some business negotiations for him in Scandinavia, trying to recoup some of his losses. Wollstonecraft undertook this difficult and hazardous trip with only her young daughter and a maid. She recounted her travels and thoughts in letters to Imlay, many of which were eventually published as Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark in 1796.[27] When she returned to England and came to the full realization that her relationship with Imlay was over, she attempted suicide for the second time. In a very deliberate manner, she went out on a rainy night and “to make her clothes heavy with water, she walked up and down about half an hour” and then jumped into the Thames, but someone saw her jump and rescued her.[28] Wollstonecraft considered her suicide deeply rational, writing after her rescue, “I have only to lament, that, when the bitterness of death was past, I was inhumanly brought back to life and misery. But a fixed determination is not to be baffled by disappointment; nor will I allow that to be a frantic attempt, which was one of the calmest acts of reason. In this respect, I am only accountable to myself. Did I care for what is termed reputation, it is by other circumstances that I should be dishonoured.”[29]

Slowly, Wollstonecraft returned to her literary life, becoming involved with Joseph Johnson’s circle again and in particular with Mary Hays, Elizabeth Inchbald, and Sarah Siddons through William Godwin. Godwin and Wollstonecraft’s unique courtship began slowly but it eventually became a passionate love affair.[30] Godwin had read her Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark and later wrote that “If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book. She speaks of her sorrows, in a way that fills us with melancholy, and dissolves us in tenderness, at the same time that she displays a genius which commands all our admiration.”[31] Once Wollstonecraft became pregnant, though, they decided to marry so that their child would be legitimate. This event revealed the fact that Wollstonecraft had never been married to Imlay and as a result she and Godwin lost many friends. Godwin himself also received quite a drubbing as he had advocated for the abolition of marriage in his philosophical treatise Political Justice.[32] After their marriage on March 29, 1797, they moved into two adjoining houses, known as The Polygon, so that they could both still retain their independence; they often communicated by letter.[33] By all accounts, theirs was a happy and stable, though tragically short, relationship.

Death and Godwin’s memoirs

On August 30, 1797, Wollstonecraft gave birth to her second daughter, Mary. Although the delivery seemed to go well initially, in fact, parts of the placenta were left inside Wollstonecraft's uterus and they became infected. On September 10, she died of puerperal fever. Godwin was devastated; he wrote to a friend “I firmly believe there does not exist her equal in the world. I know from experience we were formed to make each other happy. I have not the least expectation that I can now ever know happiness again.”[34] She was buried at Old Saint Pancras Churchyard and there is a memorial to her there (though both her and Godwin's remains were later moved to Bournemouth). Her tombstone reads, “Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: Born 27 April, 1759: Died 10 September, 1797.”[35]

In January of 1798 Godwin published his Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Although Godwin felt that he was portraying his wife with love, compassion, and sincerity, many people were shocked that he would reveal Wollstonecraft’s illegitimate children, love affairs, and suicide attempts.[36] Robert Southey accused him of “the want of all feeling in stripping his dead wife naked.”[37] In fashioning a picture of Wollstonecraft, Godwin recreates her as a woman deeply invested in feeling who was balanced by his reason and portrayed her as more of a religious skeptic than her own writings suggest that she was.

Legacy

Wollstonecraft has had what Cora Kaplan labels a “curious” legacy: “for an author-activist adept in many genres… up until the last quarter-century Wollstonecraft’s life has been read much more closely than her writing.”[38] After the devastating effect of Godwin's Memoirs, Wollstonecraft's reputation lay in tatters for a century; she was even pilloried by such writers as Maria Edgeworth who clearly patterened the "freakish" Harriet Freke in Belinda (1801) after her. It was not until the late nineteenth century that one could begin to speak laudably of Wollstonecraft again. With the advent of the feminist movement, women as politically dissimilar from each other as Virginia Woolf and Emma Goldman embraced Wollstonecraft’s life story and celebrated her “experiments in living”, as Woolf termed them in a famous essay.[39] Many, of course, still continued to decry her lifestyle. It was not until the 1960s and 1970s, with the advent of feminist criticism in academia, that Wollstonecraft’s works came back into prominence. Their fortunes reflected that of the feminist movement itself. For example, in the early 1970s, six major biographies of Wollstonecraft were published that presented her “passionate life in apposition to [her] radical and rationalist agenda.”[40] Wollstonecraft was seen as a paradoxical yet intriguing figure who did not adhere to the 1970s version of feminism—“the personal is the political.” In the 1980s and 1990s, though, yet another Wollstonecraft emerged; this one was much more a creature of her time; scholars such as Claudia Johnson, Gary Kelly, and Virginia Sapiro demonstrated the continuity between Wollstonecraft’s thought and other important eighteenth century ideas such as sensibility, economics, and political theory.

Major works

Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787) and Original Stories (1788)

Wollstonecraft’s first two works revolved around education. The first, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, was a conduct book, that is, it gave advice not only on moral issues such as benevolence[41] but also on the etiquette of dress.[42] In writing such a text, Wollstonecraft was joining a large and growing market; such texts were extremely popular throughout the eighteenth century, particularly for the emerging middle class who saw in them a way to develop their own code that would challenge the aristocratic code of manners.[43] While much of what Wollstonecraft wrote in this text is unoriginal and platitudinous, there are moments, such as her description of the suffering single woman,[44] that suggest she was not content to simply repeat other conduct books.

One year later in Original Stories from Real Life Wollstonecraft wrote another text about teaching, this one for children. In it, two young girls, Mary and Caroline (named after two of Lady Kingsborough’s daughters) are instructed by a wise and benevolent maternal figure, Mrs. Mason. Throughout this text, Wollstonecraft emphasizes the importance of rational thought in female education,[45] a theme that would become a hallmark throughout her works. The girls are encouraged to feel sympathy for animals and for the poor but they are specifically warned not to let their emotions run away with them; it is this balance between reason and passion that allows them to become charitable adults.

Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790)

In 1790 Edmund Burke published Reflections on the Revolution in France. Burke, who had been a supporter of the American Revolution, shocked his contemporaries by arguing against the French revolutionaries. His book set off what is now known as the “Revolution Controversy”, a pamphlet war responding to Burke’s text.[46] Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Men was the first of many sallies in a war that included other such seminal works as Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man. But Wollstonecraft was not just responding to Burke’s Reflections, she was also responding to Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1756) in which, among other things, he argued that the beautiful was associated with weakness and femininity and that the sublime was associated with strength and masculinity. Wollstonecraft turns Burke’s rhetoric in the Reflections against him; she argues that his theatrical staging, such as the famous scene in which he describes the horrors Marie Antoinette had to undergo in florid and overblown prose, turn all of the citizens into weak women who are swayed by show.[47] She also critiques Burke’s argument by focusing on class, demonstrating like many other critics of Burke, that he was only moved by Marie Antoinette’s suffering, but not by the plight of the poor, starving women in France. Wollstonecraft argues strongly for the use of reason rather than for Burke’s reliance on tradition in government; for example, under his system, she explains, we would be obligated to continue slavery because our ancestors held slaves.[48] Wollstonecraft does not reject the need for sympathy in human relations, she almost always makes the point that sympathy is insufficient for social cohesion (at one point she writes “Such misery demands more than tears–I pause to recollect myself” [49])—one must always also analyze any situation rationally. Interestingly, though, she ends the Vindication of the Rights of Men with a reference to the Bible: “He fears God and loves his fellow-creatures. Behold the whole duty of man!”[50]

Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman consists of a hybrid of genres, everything from a political treatise, to a conduct book, to an educational treatise. In order to discuss the position of women in society, Wollstonecraft outlines the connections between four terms: rights, reason, virtue, and duty. Importantly, rights and duties are integrally linked for Wollstonecraft—if one has civic rights, then one also has civic duties. As she succintly states, “without rights there cannot be any incumbent duties."[51]

One of the main lines of argument in VRW is that women should be educated, and educated rationally, so that they can make contributions to society. Wollstonecraft responds quite vitriolically to conduct-book writers such as James Fordyce and John Gregory and educational philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau who argue that a woman does not need a rational education. (Rousseau famously argues in Emile that women are educated for the pleasure of men.) She argues that wives should be the rational "companions" of their husbands[52] and that, perhaps even more importantly, if a society is leaving the education of its children to women, those women must be well-educated in order to pass on knowledge to the next generation. Wollstonecraft argues that women are silly and superficial (she refers to them, for example, as "spaniels" and "toys" at one point[53]) not because of an innate deficiency of mind but because men have denied them access to education. What Wollstonecraft is most intent on pointing out is the limitations that women's educations have placed on them. In a poetic phrase, she writes: “Taught from their infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and, roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison.”[54] The implication behind such a statement, of course, is that without the damaging ideology foisted upon young women at an early age that focused their attention on beauty and outward accomplishments, women could do much more.

It is debatable to what extent Wollstonecraft believed that women were equal to men; certainly she was not a feminist in the modern sense of the word (the words "feminist" and "feminism" did not come into existence until the 1890s[55]) and she was not calling for equal rights or suffrage in her texts. But she does claim that all men and women are equal in the eyes of God that they are all subject to the same moral laws[56] Such claims of equality, though, can be contrasted with her statements respecting the priority of masculine strength and valor.[57] Wollstonecraft famously and ambiguously states: "Let it not be concluded that I wish to invert the order of things; I have already granted, that, from the constitution of their bodies, men seem to be designed by Providence to attain a greater degree of virtue. I speak collectively of the whole sex; but I see not the shadow of a reason to conclude that their virtues should differ in respect to their nature. In fact, how can they, if virtue has only one eternal standard? I must therefore, if I reason consequentially, as strenuously maintain that they have the same simple direction, as that there is a God.”[58]

One of Wollstonecraft's most scathing criticisms in VRW is against false and excessive sensibility, particularly in women. She argues that women who succumb to sensibility are "blown about by every momentary gust of feeling"[59] and because they are "the prey of their senses" they cannot think rationally. In fact, she claims, they do harm not only to themselves but to the entire civilization. These are not women who can help refine a civilization (a popular eighteenth century idea) but women who will destory it. Wollstonecraft does not argue that reason and feeling should act independently of each other; she claims, rather, that they should inform each other. This is clear in her own writing style which becomes very passionate at times.

In addition to her larger philosophical arguments, Wollstonecraft lays out specific suggestions for an educational model. In Chapter 12, “On National Education”, she argues that all children should be sent to a “country day school” but also given some education at home “to inspire a love of home and domestic pleasures.” She also maintains that schooling should be co-educational, arguing that men and women, whose marriages are “the cement of society”, should be “educated after the same model.”

Wollstonecraft addressed her text to the middle-class, what she called the “most natural state”. In many ways, it is restricted by and encourages a bourgeois view of the world.[60] She encourages modesty and industry and attacks the wealthy using the same language that she uses to accuse women of worthlessness. Yet, she is not exactly a friend to the poor. In her national plan for education, she suggests that, after the age of nine, the poor be separated from the rich and taught in another school.[61]

Mary (1788) and Maria (1798)

Both of Wollstonecraft’s novels focus on the desperate plight of women during the eighteenth century. In her first novel, Mary: A Fiction (1788), the protagonist, initially ignored as a child, suddenly becomes an heiress; she is consequently married off by her family as part of property deal to a man she doesn’t even know—Charles. Interestingly, Charles disappears from the scene of the novel at this point and most of the story focuses on the friendship between Mary and her sickly friend, Ann. They travel to the continent together in hopes of improving Ann’s health, but to no avail; she dies. (This section of the novel clearly mirrors the part of Wollstonecraft's own life when she and Fanny Blood had a close friendship and she went to Europe to nurse her.) While there, Mary meets and falls in love with Henry. After Ann dies, Mary and Henry return to England. Henry is also ill but Mary chooses to live with him and his mother during his last remaining weeks. Mary never really recovers from these losses and when her husband returns at the end of the book, she cannot bear to be in the same room with him. The end of the novel suggests that she will die young. Like Maria, this book is a comment on marriage. There are no successful marriages in the novel and at the end Mary says, as she seems to be dying, “She thought she was hastening to that world where there is neither marrying, nor giving in marriage,” presumably a positive state of affairs. The only successful relationships in this book are friendships, although even those end tragically for Mary.

Maria is an unfinished novel and often considered Wollstonecraft’s most radical work. In it she details many of “the wrongs of woman” not only on an individual level but on a systemic level as well. The heroine, Maria, is imprisoned in an asylum by her profligate husband in order to steal her money; even more horrifically, her child is also stolen from her. While there, Maria befriends one of the “nurses”, Jemima, who also has a harrowing tale to tell of married life, giving Wollstonecraft an opportunity to elaborate on the trials of the lower class as well as the middle class. The two women share a bond because they have both been wronged in marriage—this is one of the first moments in the history of feminism when we see an argument being made that women of all classes have the same interests. Wollstonecraft herself would not have made the argument a mere six years earlier. Because the novel is unfinished, the resolution of the “romance” plot is unclear. While imprisoned Maria meets and perhaps falls in love with a man named Darnford but one cannot be sure from the remaining scraps of the manuscript whether or not he will be able to rescue Maria, that is, one cannot tell if Wollstonecraft intended to end the novel tragically or comedically (romantically).

Bibliography

- Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787)

- Mary: A Fiction (1788)

- Original Stories from Real Life (1788)

- Of the Importance of Religious Opinions (1788) (translation)

- The Female Reader (1789) (anthology)

- Young Grandison (1790) (translation)

- Elements of Morality (1790) (translation)

- A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790)

- A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)

- An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution (1794)

- Letters Written during a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark (1796)

- Contributions to the Analytical Review (1788-1797) (published anonymously)

- The Cave of Fancy (1798, published posthumously; fragment)

- Maria, or The Wrongs of Woman (1798, published posthumously; unfinished)

- Letters to Imlay (1798, published posthumously)

- Letters on the Management of Infants (1798, published posthumously; unfinished)

- Lessons (1798, published posthumously; unfinished)

- On Poetry and our Relish for the Beauties of Nature (1798, published posthumously)

Notes and references

- ^ Tomlin, Claire. The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft. New York: Penguin Books (1992), 17, 24, 27.

- ^ Todd, Janet. Mary Wollstonecraft: A Revolutionary Life. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson (2000), 11.

- ^ Todd, 45-57.

- ^ Todd, 16.

- ^ Tomlin, 54-5 and 56-7.

- ^ Todd, 62.

- ^ Todd, 68-9; Tomlin, 52ff.

- ^ See, for example, Todd, 106-7.

- ^ Todd, 116.

- ^ National Union Catalogue.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Mary. The Collected Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Janet Todd. New York: Penguin (2003), 139.

- ^ Todd, 123; Tomlin, 91-2.

- ^ Todd, 134-5.

- ^ For an analysis and a list of Wollstonecraft’s reviews, see Mitzi Myers, "Sensibility and the 'Walk of Reason': Mary Wollstonecraft’s Literary Reviews as Cultural Critique,” Sensibility in Transformation: Creative Resistance to Sentiment from the Augustans to the Romantics, Ed. Syndy McMillen Conger (Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1990).

- ^ Quoted in Todd, 153.

- ^ Todd, 197-8; Tomlin 151-2.

- ^ See, for example, Todd, 72-5.

- ^ Todd, 214-5.

- ^ Todd, 232-235.

- ^ Tomlin, 185-6.

- ^ Todd, 235-6.

- ^ Tomlin, 218.

- ^ St Clair, William. The Godwins and the Shelleys: The biography of a family. New York: W. W. Norton and Co. (1989), 160.

- ^ Tomlin, 225.

- ^ Todd, Chapter 25.

- ^ Todd, 286-7.

- ^ Tomlin, 225-231.

- ^ Todd, 355-6.

- ^ Quoted in Todd, 357.

- ^ St. Clair, 164-9.

- ^ Godwin, William. Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Eds. Pamela Clemit and Gina Luria Walker. Peterborough: Broadview Press (2001), 95.

- ^ St. Clair, 172-174.

- ^ St. Clair, 173.

- ^ William Godwin to Thomas Holcroft, September 10, 1797. William Godwin: His Friends and Contemporaries. Ed. C. Kegan Paul. London: Henry S. King and Co. (1876).

- ^ Todd, 457.

- ^ St. Clair, 182-8.

- ^ Robert Southey to William Taylor, July 1, 1804. A Memoir of the Life and Writings of William Taylor of Norwich. Ed. J. W. Robberds. 2 vols. London: John Murray (1824) 1:504.

- ^ Kaplan, Cora. “Mary Wollstonecraft’s reception and legacies.” The Cambridge Companion to Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Claudia L. Johnson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2002), 247.

- ^ Woolf, Virgina. “The Four Figures”.

- ^ Kaplan, 254.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Mary. Thoughts on the Education of Daughters. London: Printed by J. Johnson (1787), 135-7.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Thoughts, 35-7.

- ^ Kelly, Gary. Revolutionary Feminism: The Mind and Career of Mary Wollstonecraft. London: Macmillan (1992), 31

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Thoughts, 73-8.

- ^ Myers, Mitzi. "Impeccable Governesses, Rational Dames, and Moral Mothers: Mary Wollstonecraft and the Female Tradition in Georgian Children’s Books." Children’s Literature 14 (1986): 31-59.

- ^ See, for example, Marilyn Butler, ed., Burke, Paine, Godwin, and the Revolution Controversy, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Mary. The Vindications: The Rights of Men and The Rights of Woman, Eds. D.L. Macdonald and Kathleen Scherf. Toronto: Broadview Literary Texts (1997), 45.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 44.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 96.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 95.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 282.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 192.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 144.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 157.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ See, for example Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 126, 146.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 110.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 135.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 177.

- ^ See, for example, Gary Kelly, Revolutionary Feminism: The Mind and Career of Mary Wollstonecraft. London: Macmillan (1992).

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 311.

Further reading

- Conger, Syndy McMillen. Mary Wollstonecraft and the Language of Sensibility. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1994.

- Falco, Maria J., ed. Feminist Interpretations of Mary Wollstonecraft. University Park: Penn State Press, 1996.

- Flexner, Eleanor. Mary Wollstonecraft. New York: Penguin, 1972.

- Godwin, William. Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Eds. Pamela Clemit and Gina Luria Walker. Peterborough: Broadview Press Ltd., 2001.

- Janes, R.M. "On the Reception of Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman". Journal of the History of Ideas 39 (1978): 293-302.

- Johnson, Clauda L., ed. The Cambridge Companion to Mary Wollstonecraft. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Johnson, Claudia L. Equivocal Beings: Politics, Gender, and Sentimentality in the 1790s. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Kelly, Gary. Revolutionary Feminism: The Mind and Career of Mary Wollstonecraft. New York: St. Martin's, 1992.

- Myers, Mitzi. "Impeccable Governess, Rational Dames, and Moral Mothers: Mary Wollstonecraft and the Female Tradition in Georgian Children's Books." Children's Literature 14 (1986):31-59.

- Myers, Mitzi. "Sensibility and the 'Walk of Reason': Mary Wollstonecraft's Literary Reviews as Cultural Critique." Sensibility in Transformation: Creative Resistance to Sentiment from the Augustans to the Romantics. Ed. Syndy Conger Mcmillen. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1990.

- Poovey, Mary. The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer: Ideology as Style in the Works of Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley and Jane Austen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- Sapiro, Virginia. A Vindication of Political Virtue: The Political Theory of Mary Wollstonecraft. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- Taylor, Barbara. Mary Wollstonecraft and the Feminist Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Todd, Janet. Mary Wollstonecraft: A Revolutionary Life. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 2000.

- Tomalin, Claire. The Life and Death of May Wollstonecraft. Penguin, 1992. ISBN 0-231-12184-9

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. The Complete Works of Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Janet Todd and Marilyn Butler. 7 vols. London: William Pickering, 1989.

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. The Complete Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Janet Todd. New York: Penguin Books, 2003.

External links

- Works by Mary Wollstonecraft at Project Gutenberg

- Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman, by William Godwin, at Project Gutenberg

- A short biography at The History Guide

- Free digitally-voiced audiobook of Mary: A Fiction at Babblebooks.com